1 Gestural Abstraction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Fernando Botero

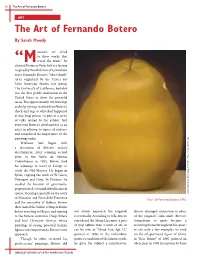

36 The Art of Fernando Botero ART The Art of Fernando Botero By Sarah Moody useums are afraid to show works that “Mreveal the truth.” So claimed Professor Peter Selz in a lecture inspired by the exhibition of Colombian artist Fernando Botero’s “Abu Ghraib” series organized by the Center for Latin American Studies last spring. The University of California, Berkeley was the fi rst public institution in the United States to show the powerful series. The approximately 100 drawings and oil paintings resulted from Botero’s shock and rage at what had happened at that Iraqi prison. As part of a series of talks related to the exhibit, Selz examined Botero’s development as an artist in relation to topics of violence and considered the importance of the paintings today. York. New Gallery, Image courtesy of Marlborough Botero. © Fernando Professor Selz began with a discussion of Botero’s artistic development. After winning second prize in the Salón de Artistas Colombianos in 1952, Botero used his winnings to travel to Europe to study the Old Masters. He began in Spain, copying the work of El Greco, Velázquez and Goya. In Florence, he studied the location of generously- proportioned, verisimilar bodies in real spaces, focusing especially on the work of Masaccio and Piero della Francesca “Pear” by Fernando Botero, 1976. and the sensuality of Rubens. Botero then visited the Sistine ceiling in Rome before traveling to Mexico and turning not always approach the originals almost deranged expression in place to the famous muralists Diego Rivera reverentially. According to Selz, Botero of the original’s calm smile. -

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Formalism Post- Formalism

FORMALISM POST- FORMALISM nonsite.org is an online, open access, peer-reviewed quarterly journal of scholarship in the arts and humanities 7 affiliated with Emory College of Arts and Sciences. 2014 all rights reserved. ISSN 2164-1668 EDITORIAL BOARD Bridget Alsdorf Ruth Leys James Welling Jennifer Ashton Walter Benn Michaels Todd Cronan Charles Palermo Lisa Chinn, editorial assistant Rachael DeLue Robert Pippin Michael Fried Adolph Reed, Jr. Oren Izenberg Victoria H.F. Scott Brian Kane Kenneth Warren SUBMISSIONS ARTICLES: SUBMISSION PROCEDURE Please direct all Letters to the Editors, Comments on Articles and Posts, Questions about Submissions to [email protected]. Potential contributors should send submissions electronically via nonsite.submishmash.com/Submit. Applicants for the B-Side Modernism/Danowski Library Fellowship should consult the full proposal guidelines before submitting their applications directly to the nonsite.org submission manager. Please include a title page with the author’s name, title and current affiliation, plus an up-to-date e-mail address to which edited text and correspondence will be sent. Please also provide an abstract of 100-150 words and up to five keywords or tags for searching online (preferably not words already used in the title). Please do not submit a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere. 1 ARTICLES: MANUSCRIPT FORMAT Accepted essays should be submitted as Microsoft Word documents (either .doc or .rtf), although .pdf documents are acceptable for initial submissions.. Double-space manuscripts throughout; include page numbers and one-inch margins. All notes should be formatted as endnotes. Style and format should be consistent with The Chicago Manual of Style, 15th ed. -

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

Despite the Stereotype That an Artistic Stage of Cracow After World War 2

uart ↪Q Nr 3(25)/2012 Summary TOMASZ GRYGLEWICZ/ Geometric Abstraction in Cracow artistic milieu in 1960-2010 Despite the stereotype that an artistic stage of Cracow after World War 2 was domi- nated by Colourism, Surrealism, Tachisme and Matter Painting – distinctly present in the circle of the Second Krakow Group and its leader Tadeusz Kantor, and in the later period dominated by expressionistic figuration, we may also observe in the Cra- cow milieu a significant interest for cold Geometric Abstraction that is based on opti- cal effects. Especially after 1960 we can follow in Cracow development of various tendencies in Geometric Abstraction to name only Op Art, Minimal Art or Post Painterly Abstrac- tion. This development was undoubtedly affected by succeeding exhibitions of the International Print Biennial (at present Print Triennial) within which works from this artistic circle appeared next to popular in the 1960s Pop Art. Different versions of Geometric Abstraction were practised, for instance, by the following artists: Alina Kalczyńska, Ryszard Otręba and Jan Pamuła who, as one of the first artists in Poland, paid his attention to computer graphic art. The initiated in the 1960s trend for Geo- metric Abstraction in Cracow painting and graphics has been continued till today, being at the same time an alternative to figurative tendencies and multimedia art. The author discusses the succeeding generations of artists from Cracow dealing with Geometric Abstractionism, starting from emigrant artist Mieczysław Janikowski, who studied in Cracow as early as before the war and was a joint between inter-war and post-war avant-garde, and reaching at the Action of Abstraction Revaluation, un- dertaken by the Cracow gallery F.A.I.T in 2008–2009 with participation of the young- est artistic generation. -

Lucio Fontana

Lucio Fontana. Concetto spaziale, La luna a Venezia, 1961. 54 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/152638101317127813 by guest on 27 September 2021 Lucio Fontana: Between Utopia and Kitsch ANTHONY WHITE Consumption as spectacle contains the promise that want will disappear . It is the desire for a new ecology, for a breaking down of environmental barriers, for an esthetic which is not limited to the sphere of “the artistic.” These desires . have physiological roots and can no longer be suppressed. Consumption as spectacle is—in parody form—the anticipation of a utopian situation. —Hans Magnus Enzensberger1 In late 1961 the Argentine-Italian artist Lucio Fontana mounted his first North American solo exhibition at New York’s Martha Jackson Gallery. Titled “Ten Paintings of Venice,” the exhibition consisted of canvases that had been punc- tured with a knife and embellished with unorthodox materials. In these works, dedicated to the Byzantine splendors of Venice, dazzling layers of metallic gold or silver paint had been thickly troweled on with a spatula. Then, with the fingers of either hand, the wet paint was pockmarked with dabs, or raked into dense ridges that roughly formed squares, circles, or decorative swirls. Some works were also encrusted with shattered chips of polychrome Murano glass. In showing at Martha Jackson, Fontana was engaging in a dialogue with the most progressive art in New York of the time. The previous year the gallery had hosted “New Media—New Forms,” where the art of junk and industrial debris found its first uptown venue. In 1961 the gallery showed “Environments, Situations, Spaces,” which included Claes Oldenburg’s garish plaster reliefs of cheap com- modities; Allan Kaprow’s Yard, a courtyard filled with car tires; and George Brecht’s Chair Events, ordinary furniture considered as performance works. -

Art in 1960S

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1960s A form of abstract art that emphasized spontaneous, intuitive creation of unstructured expressions of the artist’s unconscious Action Painting: emphasized the dynamic handling of paint and techniques that were partly dictated by chance. The act of painting was as significant as the finished work: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1975 Color-Field Painting: used large, soft-edged fields of flat color: Mark Rothko, Ab Reinhardt Mark Rothko, Lot 24, “No. 15,” 1952 “A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high…a pure, abstract, non- objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting -- an object that is self conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti-art). Ad Reinhardt, Abstract Painting,1963 –Ad Reinhardt Minimalism 1960s rejected emotion of action painters sought escape from subjective experience downplayed spiritual or psychological aspects of art focused on materiality of art object used reductive forms and hard edges to limit interpretation tried to create neutral art-as-art Frank Stella rejected any meaning apart from the surface of the painting, what he called the “reality effect.” Frank Stella, Sunset Beach, Sketch, 1967 Frank Stella, Marrakech, 1964 “What you see is what you see” -- Frank Stella Postminimalism Some artists who extended or reacted against minimalism: used “poor” materials such felt or latex emphasized process and concept rather than product relied on chance created art that seemed formless used gravity to shape art created works that invaded surroundings Robert Morris, Felt, 1967 Richard Serra, Cutting Device: Base Plat Measure, 1969 Hang Up (1966) “It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. -

Mark Tobey in 40 Years Explores Artist’S Groundbreaking Contributions to American Modernism

PRESS RELEASE First U.S. Retrospective of Mark Tobey in 40 Years Explores Artist’s Groundbreaking Contributions to American Modernism Organized by the Addison Gallery of American Art, Mark Tobey: Threading Light presents extraordinary breadth, nuance, and radical beauty of artist’s work Andover, Massachusetts (September 27, 2017) – The first comprehensive retrospective of Mark Tobey in the U.S. in 40 years will open at the Addison Gallery of American Art on November 4, 2017. Organized by the Addison Gallery of American Art, Mark Tobey: Threading Light traces the evolution of Tobey’s groundbreaking style and his significant, yet Eventuality, 1944. Tempera on paper mounted on board; 10 x 14 15/16 in. under-recognized, contributions to Addison Gallery of American Art abstraction and mid-century American modernism. Comprised of 67 paintings spanning the 1920s through 1970, Threading Light includes three exceptional works from the Addison’s renowned collection of American art and major loans from the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Tate Modern, and Centre Pompidou, among numerous other collections. Organized by the Addison and guest curator Debra Bricker Balken, who also authored the accompanying catalogue, Threading Light opened earlier this year at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice during the 2017 Venice Biennale, and will be on view at the Addison, which is located on the campus of Phillips Academy in Andover, MA, from November 4, 2017, through March 11, 2018. “As an institution dedicated to provoking new discourse and insights into the field of American art, we are delighted to share with our visitors a groundbreaking re-appraisal of one of the foremost American artists to emerge from the 1940s, a decade that saw the rise of Abstract Expressionism,” said Judith F. -

ACTION | ABSTRACTION Alberto Burri Lucio Fontana

ACTION | ABSTRACTION Alberto Burri Lucio Fontana PRESS RELEASE 14th January 2019 TORNABUONI ART LONDON - 46 Albemarle St, W1S 4JN London Exhibition: 8th February - 30th March 2019 Press view: 10am - 12pm from 6th to 8th February Conference: 7th March, 5pm-7pm, Royal Academy of Arts London, ‘Alberto Burri: A Radical Legacy’ moderated by Tim Marlow, Director of Programmes at the Royal Academy, with professor Bruno Corà, President of the Alberto Burri Foundation, professor Luca Massimo Barbero, Director of the Art History Institute at the Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, and professor Bernard Blistène, Director of the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. This exhibition sets out to recapture one of the most dramatic periods of Post-War art in Italy. The selection of works by the avant-garde artists Alberto Burri and Lucio Fontana will shed light on how the trauma and destruction of two world wars spurred these artists to reject representation and to return to primordial forms of communication through material and gesture – in Fontana’s case, through a simple but supremely efective piercing of the canvas surface and, in Burri’s case, a radical and sometimes violent reimagining of the expressive potential of traditionally ‘non-artistic’ materials. The show will shine a light on the correspondences and convergences between these artists who, despite their vastly difering aesthetics, now stand together as luminaries of material- based abstraction and an inspiration to an entire generation of artists who grew up in their shadow. Tornabuoni Art will explore their work in a tightly curated selection of highlights on display in the London gallery. Both artists are being honoured with institutional exhibitions this year. -

Education and Public Programs SPRING 2021

1 THE GUIDE Education and Public Programs ^ SPRING 2021 4 special events welcome 6 ADULT PROGRAMS 9 Music programs 10 Film programs This spring, LACMA’s programming is overflowing with 12 Activity exciting blends of art and culture. Discover new musicians, watch a film, experiment with intriguing ways to use art materials, and more! 14 Family Programs Our programs for adults are rich with international themes this season. Listen to the rhythms of Brazil and Cuba during 16 Art Classes Latin Sounds, enjoy a Fijian dance performance on our YouTube channel, or take a virtual cooking class that will 20 community transport you to Japan as you learn to prepare a traditional dish inspired by artist Yoshitomo Nara. For additional hands-on programs experiences, sign up for one of our virtual art classes. Jewelry-making, painting, drawing, and digital art are all 22 School and on the calendar this spring, as well as our Bon Vivant series, which offers a fun way to enjoy a virtual happy hour while Teacher Programs exploring ways to create at home. Families are encouraged to spend time together making art with a variety of materials. Kids can try yarn painting or using acrylics, colored pencils, collage, and recycled materials to create unique pieces. Teens interested in comics can learn to compose their very own! I hope you and your families will join us this season to connect and create. Warmly, Naima J. Keith Vice President, Education and Public Programs Image credit: Installation photograph, Yoshitomo Nara, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2020–21, art © Yoshitomo Nara, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA 2 3 This spring, LACMA and Snap Inc. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement.