2. Syria: a Fragmented Media System Yazan Badran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: "Torture Was My Punishment": Abductions, Torture and Summary

‘TORTURE WAS MY PUNISHMENT’ ABDUCTIONS, TORTURE AND SUMMARY KILLINGS UNDER ARMED GROUP RULE IN ALEPPO AND IDLEB, SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Cover photo: Armed group fighters prepare to launch a rocket in the Saif al-Dawla district of the Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons northern Syrian city of Aleppo, on 21 April 2013. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Miguel Medina/AFP/Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/4227/2016 July 2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 METHODOLOGY 7 1. BACKGROUND 9 1.1 Armed group rule in Aleppo and Idleb 9 1.2 Violations by other actors 13 2. ABDUCTIONS 15 2.1 Journalists and media activists 15 2.2 Lawyers, political activists and others 18 2.3 Children 21 2.4 Minorities 22 3. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Exile, Place and Politics: Syria's Transnational Civil War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8b36058d Author Hamdan, Ali Nehme Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Exile, Place, and Politics: Syria’s Transnational Civil War A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Ali Nehme Hamdan 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Exile, Place, and Politics: Syria’s Transnational Civil War by Ali Nehme Hamdan Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor John A. Agnew, Co-Chair Professor Adam D. Moore, Co-Chair This dissertation explores the role of transnational dynamics in civil war. The conflict in Syria has been described as experiencing one of the most brutal civil wars in recent memory. At the same time, it bears the hallmarks of a deeply “internationalized” conflict, raising questions about the role of transnational forces in shaping its structural dynamics. Focusing on Syria’s conflict, I examine how different actors draw on transnational networks to shape the geographies of “wartime governance.” Wartime governance has been acknowledged by many scholars to be an important process of civil wars, and yet it is frequently conceptualized as a “subnational” or “local” process. For Syria’s opposition, I investigate how it both produces decidedly transnational spaces in Syria’s Northwest, while also illuminating the role of a particular network of actors in doing so. For the global jihadi network Daesh (known also as the Islamic State), I illustrate the contrast between its rhetoric of transnational jihad and its practices of governance, which is considerable. -

Mapping Accountability Efforts in Syria

MAPPING ACCOUNTABILITY EFFORTS IN SYRIA Prepared by the Public International Law & Policy Group February 2013 PILPG Syria Transitional Justice Mapping Evaluation, February 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of Purpose 1 Introduction 1 Background on the Syrian Conflict 2 Methodology 4 Legal Framework for Transitional Justice in Syria 5 Syria’s International Legal Obligations 5 International Criminal Law 5 International Humanitarian Law 10 International Human Rights Law 15 Syria’s Domestic Legal Framework 16 The Syrian Penal Code 16 Amnesties in Transitional Justice 18 Amnesties Issued by the Syrian Government 19 Structure of the Syrian Judicial System 22 Supreme Judicial Council 23 Syrian Court Structure 23 Judicial Independence 26 The Transitional Justice Evidence Documentation Process 27 TJE Collection 28 TJE Compilation 28 Facilitation and Training 29 Other Activities 29 TJE Collection in Syria 30 Syrian Groups and Organizations 30 Civil Society Organizations 30 News Agencies 31 International Organizations 31 Intergovernmental Organizations and Bodies 31 Governmental Initiatives 32 Non-governmental Organizations 32 PILPG Syria Transitional Justice Mapping Evaluation, February 2013 News Agencies 33 Needs and Challenges for TJE Documentation Efforts in Syria 33 Deteriorating Security Situation in Syria 34 Coordinating Efforts 35 Lack of Comprehensive International Legal Approach 36 Inconsistent Verification Standards 37 Reaching All Affected Areas and Populations 37 Rape and Sexual Violence 38 Unbiased Documentation of Violations by All -

The Politics of Syria

H-Announce The Politics of Syria Announcement published by Priyadarshini Gupta on Monday, February 15, 2021 Type: Call for Papers Date: February 14, 2021 to April 20, 2021 Subject Fields: Area Studies, Diplomacy and International Relations, Cultural History / Studies, Islamic History / Studies, Literature Call for Papers (Spring Issue 2021) The image of Syria as a war-torn country has always dominated global news cycles. On one hand, news outlets discuss how the international powers serve their own economic and political interests by implementing the Middle East Grand Strategy revolving around ‘ Creative Chaos’ policies. In short, waging a proxy war on Syria’s political and economic system, destroying culture and infrastructure, affecting civilians, violating human rights principles under the pretext of democracy and protection of human rights, with the aim to reshape Middle East politics. In this context, such news cycles persistently distort President Assad's counterstrategy. On the other hand, the media’s coverage of the civilians’ struggle to survive daily has garnered sympathy from people around the world. In this edition, we seek scholarly and opinionated papers that explore topics, discourses, motifs, interests, or perspectives that go beyond the image of Syria as a conflict zone, or the country which is the product of a conflict zone. This edition is looking for scholarly and critical interventions that write back to such limited and binary representations of Syria. The issue aims to incentivize Syria in a positive light, focussing on the contributions of Syria (politically, economically, literarily, historically, and socially) in the world order. Our aim is to engage in such current scholarly conversations that pushback, complicate, and uncomplicate our monolithic and true Substantive Due Process issues allowing the states' power to regulate certain visions of Syria. -

“Targeting Life in Idlib”

HUMAN RIGHTS “Targeting Life in Idlib” WATCH Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Copyright © 2020 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: https://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2020 ISBN: 978-1-62313-8578 “Targeting Life in Idlib” Syrian and Russian Strikes on Civilian Infrastructure Map .................................................................................................................................. i Glossary .......................................................................................................................... ii Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Syria's Alawites and the Politics of Sectarian Insecurity

Syria’s Alawites and the Politics of Sectarian Insecurity: A Khaldunian Perspective* Leon Goldsmith** Abstract Since 2000 there has been varied academic analysis about the nature and direction of modern Syrian politics. The Syrian political crisis which began March 15, 2011 however, came as a surprise to most, and will no doubt spark a new round of debate about its causes and possible effects. One aspect that has been widely overlooked or misread is the critical role of the Syrian Alawite community in determining Syria’s future. Ongoing Alawite support to the Asad regime is by no means assured. The foundations of Alawite approval of the regime have steadily eroded during the second generation of Asad rule in a process, which resembles Ibn Khaldun’s theo- ry for the decline of group ‘asabiyya in the second stage of dynasties. The one resilient factor that ties the Alawite community to the Syrian regime however, is sectarian insecurity. The Asad regime requires, and promotes, Alawite insecurity in order to preserve its power. Nevertheless, there re- mains an opportunity, and a precedent, for Alawites to break free from this political deadlock and participate equally and openly in a ‘new’ Syria. Keywords: Syria, Alawites, Ibn Khaldun, “Asabiyya”, Sectarian Insecurity, “Arab Uprising”. Suriyeli Aleviler ve Mezhepsel Güvensizlik Politikaları: Halduncu Bir Bakış Özet 2000 yılından beri modern Suriye siyasetinin yapısına ve gidişatına ilişkin çeşitli akademik analizler yapılmaktadır. Yine de 15 Mart 2011’de başlayan Suriye’deki siyasi kriz birçok kişi için sürpriz olmakla beraber hiç şüphesiz söz konusu krizin sebeplerine ve yaratacağı muhtemel etkilere ilişkin tartışmalar da artacaktır. -

MEMP Received November 6, 2009 -- November 1, 2010

MEMP Received November 6, 2009 -- November 1, 2010 TITLE = al-Dawah. IMPRINT = London, United Kingdom. IDENTITY = MF [Neg MF]; Oct. 2004-Jul. 2006; 2 reels. NOTE = Rec'd from filmer 10-5-2010. TITLE = Ittihad al-Sha'b. IMPRINT = Baghdad, Iraq. IDENTITY = MF [Neg MF]; Jan. 1959-Sept. 1960; 3 reels. NOTE = Rec'd from filmer 8-16-10. TITLE = Kurdistan. IMPRINT = Iran. IDENTITY = MF [Neg MF]; 1979-1999, 4 reels. NOTE = Rec'd from filmer 8-16-10. TITLE = Library of Congree Arabic Pamphlet Collection Part 2 NOTE = 39 titles on 89 reels received by 8-16-10. TITLE = al-Nur IMPRINT = Dimashq : al-Ḥizb al-Shuyūī al-Sūrī, NOTE = Rec’d 2 reels (Apr. 13, 2005-May 28, 2008) 12-23-09. TITLE = Sirwan. IMPRINT = Sanadaj, Iran. IDENTITY = MF [Neg MF]; May 2000-Nov. 2005; 3 reels. NOTE = Rec'd 3 reels from filmer. 9-21-10. MEMP On Order November 6, 2009 -- November 1, 2010 TITLE = Baghdad Times. IMPRINT = Baghdad, Iraq. IDENTITY = MF; 1918-1922; 3 reels. NOTE = Ordered 9-28-10. TITLE = Hilal. IMPRINT = Istanbul, Turkey. IDENTITY = MF; 1918; 1 reel. NOTE = Ordered 9-28-10 jea. TITLE = Lloyd Ottoman. IDENTITY = MF; 1917-1918; 2 reels. NOTE = Ordered 9-28-10. TITLE = Orient News. IMPRINT = Instanbul, Turkey. IDENTITY = MF; 1919-1922; 6 reels. NOTE = Ordered 9-28-10. TITLE = Sicilli Ticaret Gazetesi ve Piyasa Cedveli. IMPRINT = Istanbul, Turkey. IDENTITY = MF [Neg. MF]; Oct. 1951-Mar. 1953; 1 reel. NOTE = Sent 1 reel (4 issues from Oct. 1951-Mar. 1953) 10-13-10. TITLE = Times of Mesopotamia. -

Institutional Adaptation to Environmental Change

Institutional Adaptation to Environmental Change Leander Heldring∗ Robert C. Alleny Mattia C. Bertazziniz November 2019 JOB MARKET PAPER. LATEST VERSION HERE Abstract In this paper we show that states form to overcome the adverse effects of environmental change. In a panel dataset of settlement, state formation, and public good provision in southern Iraq between 5000BCE and today, we estimate the effect of a series of river shifts. We hypothesize that a river shift creates a collective action problem in communally organizing irrigation, and creates demand for a state. We show four main results. First, a river shift negatively affects settlement density, and therefore incen- tivizes canal irrigation. Second, a river shift leads to state formation, centralization of existing states, and the construction of administrative buildings. Third, these states raise taxes, and build canals to replace river irrigation. Finally, where canals are built, river shifts no longer negatively affect settlement. Our results support a social contract theory of state formation: citizens faced with a collective action problem exchange resources and autonomy for public good provision. Keywords: Environmental Change, States, Collective Action, Iraq. JEL classification: O10, O13, H70, Q5. ∗Job market candidate. Institute on Behavior & Inequality (briq), Schaumburg-Lippe-Strasse 5-9 53113 Bonn, Germany. E-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.leanderheldring.com. yFaculty of Social Science, New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Marina District, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. E-mail: [email protected]. zDepartment of Economics and Nuffield College, University of Oxford, 10 Manor Road, OX1 3UQ Oxford, United Kingdom. E- mail: [email protected]. -

Explaining Syria By

Explaining Syria by Esmond Wei An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2015 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Joseph Foudy Faculty Adviser Thesis Adviser Acknowledgments I would like to extend my gratitude and appreciation to my thesis adviser, Professor Joseph Foudy. Throughout this entire process of formulating, conducting, and articulating this thesis, Professor Foudy has been there to provide insight, direction, and resources to make this entire endeavor possible. I appreciate all that he has done throughout the school year and recognize that none of this would be possible without him. I would also like to thank Professor Marti Subrahmanyam for his commitment to the Stern Honors Program. It was truly an unique program to participate in and it would not have been possible without Professor Subrahmanyam and others committing to the program in the manner that they have. Explaining Syria Abstract: The Middle-East has historically been a hotbed of tension, instability, and conflict. Yet, despite the volatile dynamics in the region, until recent years, the region has been governed surprisingly resilient regimes. Only recently, did the Arab Spring dislodge these resilient governments. As the spotlight is currently on the world’s response against the Islamic State and the ongoing civil war in Syria, the popular explanation to this conflict is that sectarianism drove Syria into this crisis. However, we believe that sectarianism alone did not cause the war. Rather, it was a regime that enacted economic policies that strengthened its grip on power but sacrificed long-term effects on growth. -

Domestic and International Sources of the Syrian and Libyan Conflicts (2011-2020)

Peer-reviewed Article International Security After the Arab Spring: Domestic and International Sources of the Syrian and Libyan Conflicts (2011-2020) EFE CAN GÜRCAN Asst. Prof. Department of International Relations, İstinye University Efe Can Gürcan is Associate Dean of Research and Development for the Faculty of Economics, Administrative and Social Sciences at İstinye University. He is also Chair of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration and a faculty member in the Department of Inter- national Relations, İstinye University. He serves as Research Associate at the University of Mani- toba’s Geopolitical Economy Research Group. Gürcan completed his undergraduate education in International Relations at Koç University. He received his master’s degree in International Studies from the University of Montréal and earned his PhD in Sociology from Simon Fraser University. He speaks English, French, Spanish and Turkish. His publications include three books as well as more than 30 articles and book chapters on international development, international conflict and international institutions, with a geographical focus on Latin America and the Middle East. His latest book is Multipolarization, South-South Cooperation and the Rise of Post-Hegemonic Governance. BRIq • Volume 1 Issue 2 Spring 2020 ABSTRACT The so-called Arab “Spring” may be considered as the most significant geopolitical event and the largest social mobilization that have shaped Greater Middle Eastern politics in the post-Cold War era. The present article examines how this process turned into an Arab “Winter”, having led to the world’s largest humanitarian crises since World War II. Using a geopolitical-economy framework guided by narrative analysis and incorporated comparison, this article focuses on the countries where the Arab Spring process led to gravest consequences: Syria and Libya. -

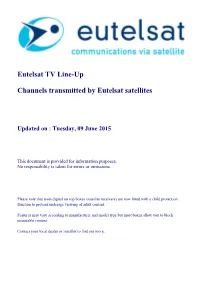

Linup Report

Eutelsat TV Line-Up Channels transmitted by Eutelsat satellites Updated on : Tuesday, 09 June 2015 This document is provided for information purposes. No responsibility is taken for errors or omissions. Please note that most digital set top boxes (satellite receivers) are now fitted with a child protection function to prevent underage viewing of adult content. Features may vary according to manufacturer and model type but most boxes allow you to block unsuitable content. Contact your local dealer or installer to find out more. Freq Beam Analo Diff Fec Symb Acces Lang g ol Rate EUTELSAT 117 WEST A 3.720 V C Edusat package DVB-S 3/4 27.000 C Telesecundaria TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV Docencia TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 13 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C UnAD TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 15 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Canal 22 Nacional TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Telebachillerato TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 18 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Tele México TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV Universidad TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Red de las Artes TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Aprende TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Canal del Congreso TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Especiales TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Transmisiones Especiales 27 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV UNAM TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish 3.744 V C INE TV TV DVB-S2 3/4 2.665 Spanish 3.748 V C Radio Centro radio DVB-S 7/8 2.100 Spanish 3.768 V C Inti Network TV DVB-S2 3/4 4.800 Spanish 3.772 V C Gama TV TV DVB-S 3/4 3.515 BISS Spanish 3.786 V