Local Intermediaries in Post-2011 Syria Transformation and Continuity Local Intermediaries in Post-2011 Syria Transformation and Continuity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Syria and Repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP

30.11.2012 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 330/21 DECISIONS COUNCIL DECISION 2012/739/CFSP of 29 November 2012 concerning restrictive measures against Syria and repealing Decision 2011/782/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, internal repression or for the manufacture and maintenance of products which could be used for internal repression, to Syria by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be particular Article 29 thereof, prohibited, whether originating or not in their territories. Whereas: The Union shall take the necessary measures in order to determine the relevant items to be covered by this paragraph. (1) On 1 December 2011, the Council adopted Decision 2011/782/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Syria ( 1 ). 3. It shall be prohibited to: (2) On the basis of a review of Decision 2011/782/CFSP, the (a) provide, directly or indirectly, technical assistance, brokering Council has concluded that the restrictive measures services or other services related to the items referred to in should be renewed until 1 March 2013. paragraphs 1 and 2 or related to the provision, manu facture, maintenance and use of such items, to any natural or legal person, entity or body in, or for use in, (3) Furthermore, it is necessary to update the list of persons Syria; and entities subject to restrictive measures as set out in Annex I to Decision 2011/782/CFSP. (b) provide, directly or indirectly, financing or financial assistance related to the items referred to in paragraphs 1 (4) For the sake of clarity, the measures imposed under and 2, including in particular grants, loans and export credit Decision 2011/273/CFSP should be integrated into a insurance, as well as insurance and reinsurance, for any sale, single legal instrument. -

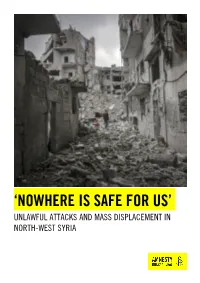

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

Bi-Weekly Update Whole of Syria

BI-WEEKLY UPDATE WHOLE OF SYRIA Issue 5 | 1 - 15 March 2021 1 SYRIA BI-WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT – ISSUE 5 | 1 – 15 MARCH 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. COVID-19 UPDATE ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1. COVID-19 STATISTICAL SUMMARY AT WHOLE OF SYRIA LEVEL .............................................................................................. 1 1.2. DAILY DISTRIBUTION OF COVID-19 CASES AND CUMULATIVE CFR AT WHOLE OF SYRIA LEVEL .................................................... 1 1.3. DISTRIBUTION OF COVID-19 CASES AND DEATHS AT WHOLE OF SYRIA LEVEL ........................................................................... 2 1.4. DISTRIBUTION OF COVID-19 CASES AND DEATHS BY GOVERNORATE AND OUTCOME ................................................................. 2 2. WHO RESPONSE ........................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. HEALTH SECTOR COORDINATION ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2. NON-COMMUNICABLE DISEASES AND PRIMARY HEALTH CARE ................................................................................................ 3 2.3. COMMUNICABLE DISEASE (CD) ....................................................................................................................................... -

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1

ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives (CHI): Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq1 S-JO-100-18-CA-004 Weekly Report 209-212 — October 1–31, 2018 Michael D. Danti, Marina Gabriel, Susan Penacho, Darren Ashby, Kyra Kaercher, Gwendolyn Kristy Table of Contents: Other Key Points 2 Military and Political Context 3 Incident Reports: Syria 5 Heritage Timeline 72 1 This report is based on research conducted by the “Cultural Preservation Initiative: Planning for Safeguarding Heritage Sites in Syria and Iraq.” Weekly reports reflect reporting from a variety of sources and may contain unverified material. As such, they should be treated as preliminary and subject to change. 1 Other Key Points ● Aleppo Governorate ○ Cleaning efforts have begun at the National Museum of Aleppo in Aleppo, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Heritage Response Report SHI 18-0130 ○ Illegal excavations were reported at Shash Hamdan, a Roman tomb in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0124 ○ Illegal excavation continues at the archaeological site of Cyrrhus in Aleppo Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0090 UPDATE ● Deir ez-Zor Governorate ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sayyidat Aisha Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0118 ○ Artillery bombardment damaged al-Sultan Mosque in Hajin, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0119 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike destroyed Ammar bin Yasser Mosque in Albu-Badran Neighborhood, al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. ASOR CHI Incident Report SHI 18-0121 ○ A US-led Coalition airstrike damaged al-Aziz Mosque in al-Susah, Deir ez-Zor Governorate. -

Annex Ii: List of Natural and Legal Persons, Entities Or Bodies Referred to in Article 14 and 15 (1)(A)

VEDLEGG II ANNEX II: LIST OF NATURAL AND LEGAL PERSONS, ENTITIES OR BODIES REFERRED TO IN ARTICLE 14 AND 15 (1)(A) A. Persons Name Identifying Reasons Date of listing information Date of birth: President of the 23.05.2011 (ب شار) Bashar .1 September Republic; person 11 (اﻷ سد) Al-Assad 1965; authorising and Place of birth: supervising the Damascus; crackdown on diplomatic demonstrators. passport No D1903 Date of birth: Commander of the 09.05.2011 (ماهر) Maher .2 (a.k.a. Mahir) 8 December 1967; Army's 4th ,diplomatic Armoured Division (اﻷ سد) Al-Assad passport No 4138 member of Ba'ath Party Central Command, strongman of the Republican Guard; brother of President Bashar Al-Assad; principal overseer of violence against demonstrators. 3. Ali ( ) Date of birth: Director of the 09.05.2011 Mamluk ( ) 19 February 1946; National Security (a.k.a. Mamlouk) Place of birth: Bureau. Former Head Damascus; of Syrian Diplomatic passport Intelligence Directorate No 983 (GID) involved in violence against demonstrators Former Head of the 09.05.2011 (عاطف) Atej .4 (a.k.a. Atef, Atif) Political Security ;Directorate in Dara'a (ن ج يب) Najib (a.k.a. Najeeb) cousin of President Bashar Al-Assad; involved in violence against demonstrators. Name Identifying Reasons Date of listing information Date of birth: Colonel and Head of 09.05.2011 (حاف ظ) Hafiz .5 April 1971; Unit in General 2 مخ لوف ) Makhluf )(a.k.a. Hafez Place of birth: Intelligence Makhlouf) Damascus; Directorate, diplomatic Damascus Branch; passport No 2246 cousin of President Bashar Al-Assad; close to Maher Al- Assad; involved in violence against demonstrators. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL NOTICE GIVEN NO EARLIER THAN 7:00 PM EDT ON SATURDAY 9 JULY 2016 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CATHLEEN COLVIN, individually and as Civil No. __________________ parent and next friend of minors C.A.C. and L.A.C., heirs-at-law and beneficiaries Complaint For of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, and Extrajudicial Killing, JUSTINE ARAYA-COLVIN, heir-at-law and 28 U.S.C. § 1605A beneficiary of the estate of MARIE COLVIN, c/o Center for Justice & Accountability, One Hallidie Plaza, Suite 406, San Francisco, CA 94102 Plaintiffs, v. SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC, c/o Foreign Minister Walid al-Mualem Ministry of Foreign Affairs Kafar Soussa, Damascus, Syria Defendant. COMPLAINT Plaintiffs Cathleen Colvin and Justine Araya-Colvin allege as follows: INTRODUCTION 1. On February 22, 2012, Marie Colvin, an American reporter hailed by many of her peers as the greatest war correspondent of her generation, was assassinated by Syrian government agents as she reported on the suffering of civilians in Homs, Syria—a city beseiged by Syrian military forces. Acting in concert and with premeditation, Syrian officials deliberately killed Marie Colvin by launching a targeted rocket attack against a makeshift broadcast studio in the Baba Amr neighborhood of Homs where Colvin and other civilian journalists were residing and reporting on the siege. 2. The rocket attack was the object of a conspiracy formed by senior members of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (the “Assad regime”) to surveil, target, and ultimately kill civilian journalists in order to silence local and international media as part of its effort to crush political opposition. -

Consejo De Seguridad Distr

Naciones Unidas S/2017/445 Consejo de Seguridad Distr. general 23 de mayo de 2017 Español Original: inglés Aplicación de las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015) y 2332 (2016) Informe del Secretario General I. Introducción 1. El presente informe es el 39º que se prepara en cumplimiento del párrafo 17 de la resolución 2139 (2014), el párrafo 10 de la resolución 2165 (2014), el párrafo 5 de la resolución 2191 (2014), el párrafo 5 de la resolución 2258 (2015) y el párrafo 5 de la resolución 2332 (2016), en que el Consejo de Seguridad solicitó al Secretario General que lo informara, cada 30 días, sobre la aplicación de las resoluciones por todas las partes en el conflicto de la República Árabe Siria. 2. La información que aquí figura se basa en los datos de que disponían los organismos de las Naciones Unidas sobre el terreno y los datos facilitados por el Gobierno de la República Árabe Siria y procedentes de otras fuentes sirias y públicas. Los datos de los organismos de las Naciones Unidas relativos a las entregas de suministros humanitarios corresponden al período comprendido entre el 1 y el 30 de abril de 2017. Recuadro 1 Cuestiones destacadas en abril de 2017 1) A pesar del alto el fuego declarado el 30 de diciembre de 2016, los combates en múltiples zonas siguieron ocasionando muertos y heridos entre la población civil y la destrucción de la infraestructura civil. 2) Las Naciones Unidas estiman que, a fines de abril, aproximadamente 624.500 personas vivían en estado de sitio en la República Árabe Siria. -

WIELAND, C. — Syrien Nach Dem Irak-Krieg. Bastion Gegen

9840_BIOR_2007/1-2_01 27-04-2007 09:05 Pagina 117 229 BOEKBESPREKINGEN — ARABICA 230 seen as having an “ethnic-national” dimension, but he does not provide a definition of what an “ethnic group” really is, as this would be outside the scope of this book: “Auf die lange Debatte der Nationalismusforschung, wie real oder kon- struiert eine Ethnie tatsächlich ist und wie sie deshalb behan- delt werden soll, kann hier leider nicht im Detail eingegan- gen werden. (p. 35). Wieland considers the so-called “ethnic-nationalist” tinted ideology of the Ba{th Party as being contradictory with its ARABICA socialism, calling this combination a “Spagat” (splits) (p. 45). His argument is that people who belong to a nation are usually classified according to “primordial characteristics” WIELAND, C. — Syrien nach dem Irak-Krieg. Bastion such as descent, whereas socialism is oriented towards social gegen Islamisten oder Staat vor dem Kollaps? classes, which come into existence because of socio-eco- (Islamkundliche Untersuchungen, 263). Klaus Schwarz nomic developments. But I do not see how it would be con- Verlag, Berlin, 2004. (23,5 cm, 169). ISBN 3-87997- tradictory to have a combination of these different categories 323-7. ISSN 0939-1940. in a single ideology. Dr. Wieland notes that relatively few books have been pub- He quotes Tibi saying that the Ba{th ideologist Michel lished on contemporary Syria for a wider public. He describes {Aflaq was “enthusiastic about Hitler” (p. 42), but does not his own book as “das Ergebnis durchdiskutierter Nächte und explain any further. Here I think Wieland should have gone zahlreicher Interviews mit Zeitzeugen wie Oppositionellen, back to primary Arabic sources (which he, in general, uses Regierungsmitgliedern und ihnen nahe stehenden Personen, rather little). -

UNRWA-Weekly-Syria-Crisis-Report

UNRWA Weekly Syria Crisis Report, 15 July 2013 REGIONAL OVERVIEW Conflict is increasingly encroaching on UNRWA camps with shelling and clashes continuing to take place near to and within a number of camps. A reported 8 Palestine Refugees (PR) were killed in Syria this week as a result including 1 UNRWA staff member, highlighting their unique vulnerability, with refugee camps often theatres of war. At least 44,000 PR homes have been damaged by conflict and over 50% of all registered PR are now displaced, either within Syria or to neighbouring countries. Approximately 235,000 refugees are displaced in Syria with over 200,000 in Damascus, around 6600 in Aleppo, 4500 in Latakia, 3050 in Hama, 6400 in Homs and 13,100 in Dera’a. 71,000 PR from Syria (PRS) have approached UNRWA for assistance in Lebanon and 8057 (+120 from last week) in Jordan. UNRWA tracks reports of PRS in Egypt, Turkey, Gaza and UNHCR reports up to 1000 fled to Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. 1. SYRIA Displacement UNRWA is sheltering over 8317 Syrians (+157 from last week) in 19 Agency facilities with a near identical increase with the previous week. Of this 6986 (84%, +132 from last week and nearly triple the increase of the previous week) are PR (see table 1). This follows a fairly constant trend since April ranging from 8005 to a high of 8400 in May. The number of IDPs in UNRWA facilities has not varied greatly since the beginning of the year with the lowest figure 7571 recorded in early January. A further 4294 PR (+75 from last week whereas the week before was ‐3) are being sheltered in 10 non‐ UNRWA facilities in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus. -

Into the Tunnels

REPORT ARAB POLITICS BEYOND THE UPRISINGS Into the Tunnels The Rise and Fall of Syria’s Rebel Enclave in the Eastern Ghouta DECEMBER 21, 2016 — ARON LUND PAGE 1 In the sixth year of its civil war, Syria is a shattered nation, broken into political, religious, and ethnic fragments. Most of the population remains under the control of President Bashar al-Assad, whose Russian- and Iranian-backed Baʻath Party government controls the major cities and the lion’s share of the country’s densely populated coastal and central-western areas. Since the Russian military intervention that began in September 2015, Assad’s Syrian Arab Army and its Shia Islamist allies have seized ground from Sunni Arab rebel factions, many of which receive support from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, or the United States. The government now appears to be consolidating its hold on key areas. Media attention has focused on the siege of rebel-held Eastern Aleppo, which began in summer 2016, and its reconquest by government forces in December 2016.1 The rebel enclave began to crumble in November 2016. Losing its stronghold in Aleppo would be a major strategic and symbolic defeat for the insurgency, and some supporters of the uprising may conclude that they have been defeated, though violence is unlikely to subside. However, the Syrian government has also made major strides in another besieged enclave, closer to the capital. This area, known as the Eastern Ghouta, is larger than Eastern Aleppo both in terms of area and population—it may have around 450,000 inhabitants2—but it has gained very little media interest.