Dialogue and Indigenous Policy in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Place of Lawyers in Politics

THE HON T F BATHURST AC CHIEF JUSTICE OF NEW SOUTH WALES THE PLACE OF LAWYERS IN POLITICS OPENING OF LAW TERM DINNER ∗ 31 JANUARY 2018 1. As a young boy learning his table manners in the 1950s, the old adage “never discuss politics in polite company” was a lesson that was not lost on me. Even for those of you who did not grow up in the era of Emily Post, I am assured the adage still holds true. 2. When I stood here to give this same address last year, I was under the naïve impression that I had given the topic a wide berth. That is, until I woke to the unwelcome image of my face splashed across the front page of the morning paper. So, eager to avoid my naivety being mistaken for political pointedness and at the risk of casting aspersions on the “polite” character of the present company, I’ve decided to throw the old rule book out the window, launch myself into the bear pit and confront the issue head on. Tonight I want to ask: to what extent should lawyers, in their professional capacity, involve themselves in political debate, criticise government policy, or advocate for particular political outcomes. 3. The particular topic was inspired, oddly enough, by an incident which occurred in discussion surrounding the same sex marriage issue. You will recall that Mr Alan Joyce, the Chief Executive Officer of Qantas came out in support of a ‘Yes’ vote at the plebiscite. It was suggested to him that he should stick to his knitting. -

Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Final Report Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale, Melissa George, Rosemary Hill and Duane Fraser Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale1, Melissa George2, Rosemary Hill3 and Duane Fraser 1The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns 2NAILSMA, Darwin 3CSIRO, Cairns Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme Project 3.9: Indigenous capacity building and increased participation in management of Queensland sea country © CSIRO, 2016 Creative Commons Attribution Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? is licensed by CSIRO for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925088-91-5 This report should be cited as: Dale, A., George, M., Hill, R. and Fraser, D. (2016) Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?. Report to the National Environmental Science Programme. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (50pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme (NESP) Tropical Water Quality (TWQ) Hub. The Tropical Water Quality Hub is part of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme and is administered by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). -

Briton-Jones

DON DUNSTAN FOUNDATION 1 DON DUNSTAN ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Sue BRITON-JONES This is George Lewkowicz from the Don Dunstan Foundation interviewing Sue Briton- Jones for the Don Dunstan History Project. The topics will be Aboriginal rights and related issues and some other areas like planning and the environment in the Dunstan years. The date today is 20th December 2007 and the location is Sue Briton-Jones’ office, 8th Floor Riverside in North Terrace, Adelaide. Sue, thanks very much for being willing to contribute to the Don Dunstan History Project. Can you just provide a short background on yourself, your studies and how you got into the public service and where you started? Well, my first degree was in Psychology at Flinders University. Subsequently I started a master’s in Town Planning at University of Adelaide, also did some part-time Law studies, and in particular in about ’96 did a course on Indigenous Australians and the Law at Flinders University. From about 1970 to ’94 I spent about ten years in Department of Premier and Cabinet, in and out, about ten years in total. I worked for the new Department of Environment when it was first established but going in and out of the public service. I worked as a management consultant for PA Management Consultants in Melbourne in about ’84–85, worked as the adviser to Susan Lenehan who was then the Minister for Environment and Planning from about 1990–91, MFP1 Development Corporation, subsequently worked for Robert Tickner who was the Commonwealth Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, and then I worked as a self- employed consultant from ’96–98 working primarily on Aboriginal issues. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright Land Rich, Dirt Poor? Aboriginal land rights, policy failure and policy change from the colonial era to the Northern Territory Intervention Diana Perche A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Government and International Relations Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Sydney 2015 Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. -

Guidelines for Preparing and Assessing Connection Material for Native Title Claims in Queensland

Guidelines for preparing and assessing connection material for Native Title Claims in Queensland November 2016 This publication has been compiled by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Services, Department of Natural Resources and Mines. © State of Queensland, 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Table of contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 2 The connection material to be provided to the State ............................................................... 4 3 The contents -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

History of the Sea of Hands Significant Dates Suggested School Activities

History of the Sea of Hands Significant Dates Suggested School Activities Sample School Program Worksheets The Sea of Hands is a great activity for students, particularlyThe Sea of if itHands supports is a community work being- baseddone in the Useful Reconciliationclassroom. Some activity schools which have can alsobe used incorporated to mark significant dates during the year, such as Sorry Day, Resources student’s own hand designs and artworks within the Nationalinstallations, Reconciliation enabling Week students and toNAIDOC make aweek. more Photo Gallery personal response to the event. ANTaR QLD can supply hands and poles which can be used free of charge if your school would like to create a Sea of Hands installation. The hands can be booked by phoning the ANTaR office on ph.0401 733359 or via email [email protected] We acknowledge the Turrubal, Jagera and Yuggera people, traditional owners of the land on which Brisbane is situated. About the Sea of Hands Sea of Hands, Canberra 1997 The first Sea of Hands was held on the 12 October 1997, in front of Parliament House, Canberra. The Sea of Hands was created as a powerful, physical representation of the Citizen's Statement on Native Title. The Citizen's Statement was a petition circulated by ANTaR to mobilise non- Indigenous support for native title and reconciliation. Plastic hands in the colours of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags, each one carrying one signature from the Citizen's Statement, were installed in front of Parliament House in what was then the largest public art installation in Australia. -

Mapping Aboriginal Nations: the ‘Nation’ Concept of Late Nineteenth Century Anthropologists in Australia

Mapping Aboriginal nations: the ‘nation’ concept of late nineteenth century anthropologists in Australia Kevin Blackburn From the late 18th century to the end of the 19th century, the word ‘nation’ underwent a change in meaning from a term describing cultural entities comprised of people of common descent, to the modern definition of a nation as a sovereign people. The politi- cal scientist Liah Greenfeld called this shift in the definition of the word nation a ‘semantic transformation’, in which ‘the meaning of the original concept is gradually obscured, and the new one emerges as conventional’.1 The historian Eric Hobsbawm noted that the New English Dictionary ‘pointed out in 1908, that the old meaning of the word envisaged mainly the ethnic unit, but recent usage rather stressed “the notion of political unity and independence”’.2 The political scientist Louis Snyder observed that the ‘Latin natio, (birth, race) originally signified a social grouping based on real or imag- inary ties of blood’. However by the end of the 19th century the term ‘nation’ had come to mean an ‘active and conscious portion of the population’, who shared a ‘common political sentiment’.3 The work of historians Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger suggests that in the 19th century a nation was not only a cultural group of people of common ethnic origin, but such a group of people who in addition believed that they were a united political entity possessing or desiring sovereignty.4 The cultural anthropologist Benedict Anderson has described the idea of the nation as an ‘imagined community’. He argued that a nation ‘is imagined because the members of even the smallest nations will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives their communion’. -

Handbook 2000

THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES S nz Faculty of Law HANDBOOK 2000 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES & Faculty of Law HANDBOOK 2000 Courses, programs and any arrangements for programs including staff allocated as stated in this Handbook are an expression of intent only. The University reserves the right to discontinue or vary arrangements at any time without notice. Information has been brought up to date as at 17 November 1999, but may be amended without notice by the University Council. © The University of New South Wales The address of the University of New South Wales is: The University of New South Wales SYDNEY 2052 AUSTRALIA Telephone: (02) 93851000 Facsimile: (02) 9385 2000 Email: [email protected] Telegraph: UNITECH, SYDNEY Telex: AA28054 http://www.unsw.edu.au Designed and published by Publishing and Printing Services, The University of New South Wales Printed by Sydney Allen Printers Pty Ltd ISSN 1323-7861 Contents Welcome 1 Changes to Academic Programs In 2000 3 Calendar of Dates 5 Staff 7 Handbook Guide 9 Faculty Information 11 General Faculty Information and Assistance 11 Faculty of Law Enrolment Procedures 11 Guidelines for Maximum Workload 11 Full-time Status 11 Part-time Status 11 Assessment of Student Progress 11 General Education Program 11 Professional Associates 12 Prizes 12 Advanced Standing 12 Cross Institutional Studies and Exchange Programs 12 Financial Assistance to Students 12 Commitment to Equal Opportunity In Education 13 Equal Opportunity in Education Policy Statement 13 Special Government Policies -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Adelaide, 8 December 1998

SPARK AND CANNON Telephone: Adelaide (08) 8212-3699 TRANSCRIPT Melbourne (03) 9670-6989 Perth (08) 9325-4577 OF PROCEEDINGS Sydney (02) 9211-4077 _______________________________________________________________ PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO AUSTRALIA'S GAMBLING INDUSTRIES MR G. BANKS, Presiding Commissioner MR R. FITZGERALD, Associate Commissioner TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT ADELAIDE ON TUESDAY, 8 DECEMBER 1998, AT 9.07 AM Continued from 7/12/98 Gambling 816 ga081298 MR BANKS: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. This is the second day of our hearings here in Adelaide for the commission's inquiry into Australia's Gambling Industries. Our first participants today are the Adelaide Central Mission. Welcome to the hearings. Could I ask you, please, to give your names and your positions. MR RICHARDS: Stephen Richards, the chief executive officer. MR GLENN: I'm Vin Glenn, and I'm a gambling counsellor at the mission. MR BIGNELL: And Trevor Bignell. I'm the manager of adult services at the mission. MR BANKS: Good. Thank you. Well, thank you very much for taking the time to come in this morning, and also for providing the submission to us, which we've read, and indeed I think we've had the benefit of an earlier submission that you provided as well for a review here in South Australia. As we indicated, why don't you perhaps highlight the key points, and then we can ask you some questions. MR RICHARDS: Okay. Thank you. The last decade has seen a rise in gambling in many western jurisdictions. It's been very very rapid and very broad in its development of products. -

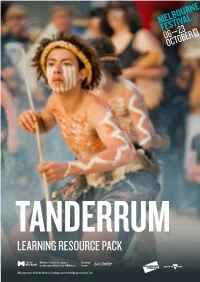

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective.