Briton-Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adelaide, 8 December 1998

SPARK AND CANNON Telephone: Adelaide (08) 8212-3699 TRANSCRIPT Melbourne (03) 9670-6989 Perth (08) 9325-4577 OF PROCEEDINGS Sydney (02) 9211-4077 _______________________________________________________________ PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION INQUIRY INTO AUSTRALIA'S GAMBLING INDUSTRIES MR G. BANKS, Presiding Commissioner MR R. FITZGERALD, Associate Commissioner TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS AT ADELAIDE ON TUESDAY, 8 DECEMBER 1998, AT 9.07 AM Continued from 7/12/98 Gambling 816 ga081298 MR BANKS: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen. This is the second day of our hearings here in Adelaide for the commission's inquiry into Australia's Gambling Industries. Our first participants today are the Adelaide Central Mission. Welcome to the hearings. Could I ask you, please, to give your names and your positions. MR RICHARDS: Stephen Richards, the chief executive officer. MR GLENN: I'm Vin Glenn, and I'm a gambling counsellor at the mission. MR BIGNELL: And Trevor Bignell. I'm the manager of adult services at the mission. MR BANKS: Good. Thank you. Well, thank you very much for taking the time to come in this morning, and also for providing the submission to us, which we've read, and indeed I think we've had the benefit of an earlier submission that you provided as well for a review here in South Australia. As we indicated, why don't you perhaps highlight the key points, and then we can ask you some questions. MR RICHARDS: Okay. Thank you. The last decade has seen a rise in gambling in many western jurisdictions. It's been very very rapid and very broad in its development of products. -

Not Just a Dream 2

For Ebony who will inherit the future 2 Towards a Partnership Society in Australia Bev Floyd 3 DRAFT BEING REVISED. FEEDBACK WELCOME. [email protected] Updated November, 2017 Not to be copied or sold for profit without permission from the author ©Bev Floyd 2017 4 Contents Introduction 1. Not just a dream 2. Social change we have inherited 3. Australia, the lucky country 4. Signs of the times 5. Governance within a partnership society 6. Husbands and wives 7. Religion within a partnership society 8. Gender in a partnership society 9. Growing older in a partnership society 10. Doing business in a partnership society 11. Minding the environment 12. Role of the media in a partnership society 13. Creativity in a partnership society 14. Ethics, responsibility and regulation 15. Australia’s future role in the world End-piece APPENDIX A: Partnership and Gladiatorial models compared APPENDIX B: Bringing about a partnership society 5 6 Introduction Not Just a Dream is my attempt to explore how far Australia has travelled along the path to a partnership society. I have not tried to write a learned or academic book. My aim has been to give a panoramic overview of social change from circa 7000 BCE to the present and to illustrate (with examples) the gradual ‘return’ to a partnership society. My definition of a partnership society is one in which ‘men’ and ‘women’ participate equally and can reach their potential to contribute to society. It is a society where poverty is minimised; race and religion are not hindrances to contribution and the environment is protected. -

Dialogue and Indigenous Policy in Australia

Dialogue and Indigenous Policy in Australia Darryl Cronin A thesis in fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Policy Research Centre Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences September 2015 ABSTRACT My thesis examines whether dialogue is useful for negotiating Indigenous rights and solving intercultural conflict over Indigenous claims for recognition within Australia. As a social and political practice, dialogue has been put forward as a method for identifying and solving difficult problems and for promoting processes of understanding and accommodation. Dialogue in a genuine form has never been attempted with Indigenous people in Australia. Australian constitutionalism is unable to resolve Indigenous claims for recognition because there is no practice of dialogue in Indigenous policy. A key barrier in that regard is the underlying colonial assumptions about Indigenous people and their cultures which have accumulated in various ways over the course of history. I examine where these assumptions about Indigenous people originate and demonstrate how they have become barriers to dialogue between Indigenous people and governments. I investigate historical and contemporary episodes where Indigenous people have challenged those assumptions through their claims for recognition. Indigenous people have attempted to engage in dialogue with governments over their claims for recognition but these attempts have largely been rejected on the basis of those assumptions. There is potential for dialogue in Australia however genuine dialogue between Indigenous people and the Australian state is impossible under a colonial relationship. A genuine dialogue must first repudiate colonial and contemporary assumptions and attitudes about Indigenous people. It must also deconstruct the existing colonial relationship between Indigenous people and government. -

2019 Storytelling: Culture, Truth-Telling and the Arts

2019 Storytelling: Culture, Truth-telling and the Arts PRESENTED BY DAVID RATHMAN AM PSM FIML Introduction: Acknowledge the Kaurna people, other traditional custodians. Elders, Lowitja O’Donoghue, The Premier of South Australia Stephen Marshall, distinguished guests and each and every one of you seated in the hall this evening. The heart of Australia’s footprint in the world is the cultural history and presence of the oldest living culture in the world. It is my intention to speak about scene setting, intent, relationship, partnership, mutual respect and unity in the address tonight. I want to take a moment to thank the many people who have worked to preserve cultural heritage, worked in the Arts, Aboriginal cultural groups, the custodians of language and country. The scientists, writers and researchers who have worked in the Universities in the city and at Adelaide University, Flinders University and University of SA ,the north terrace institutions, State Library, Art Gallery and the SA Museum, History Trust and State Records. When the Government announced the building of a centre for Aboriginal Culture and Art a group of Aboriginal people representing Native Title bodies, the Museum Aboriginal Advisory committee, Tandanya and North Terrace institutions supported by ILC and the Native Title unit worked to constructively support the vision of the Premier for a centre on lot 14 that represents the Aboriginal people’s culture through history, story of country, arts both visual and performing. We have said “it will be a place devoted to Australian Aboriginal Cultures, truth telling, art, history, science and contemporary life. A living, breathing, cultural experience “it must recognize and celebrate the longest continuous human culture on the planet, provide a dynamic cultural and economic hub and be a beacon of reconciliation for generations to come.” The Aboriginal people have cared for and respected country for over 60,000 years weaving a story of country and place that connected all that was in their midst into one story and means of existence. -

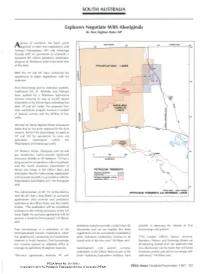

Explorers Negotiate with Aboriginals by Hon Stephen Baker MP

SOUTH AUSTRALIA Explorers Negotiate With Aboriginals By Hon Stephen Baker MP group of explo rers has been given NORTHERN 134. TERRITORY Aapproval to enter into negotiations w ith Anangu Pitjantjatjara (AP) and Maralinga Tjarutja (MT) for permission to undertake a proposed $9 million petroleum exploration program on Aboriginal lands in the north west of the State. PrrJANT JAT JARA LANDS Both the AP and M T have welcomed the opportunity to begin negotiations w ith the explorers. Fi rst Sourcenergy and its Australian partners, Traditional O il, j.F. Allender, and Oakman have applied for a Petroleum Exploration Licence covering an area of 24,397 square kilometres in the Officer Basin extending into both AP and MT lands. The proposed five• year exploration program involves a number of seismic s urveys and the drilling of four ~ wells. lii "'~ Minister for Mines Stephen Baker announced today that he has given approval for the joint venture, led by First Sourcenergy, to apply to AP and MT for permission to carry o ut pet roleum exploration within the Pitjantjatjara and Maralinga Lands. AP D irector Puntju Thompson sa id oil and gas production could provide significant 100 200 economic benefits to A P members. "AP has a KLOMETRES long record of co-operation with oil explorers and the South Australian Department of Mines and Energy in the Officer Basin and PETROLEUM TENEMENTS anticipates that the forthcoming negotiations will proceed smoothly in accordance w ith the =--~---~ :::,.,~ lk:wn fSSl Pitjantjatjara Land Rights Act," Mr Thompson said. 34. omcer Basn - south Aus1lolla The Administrator of MT, Dr Archie Barton, PETROLEUM TENEMENTS and ABORIGiNAL LANDS sa id the MT had a long history of successful agreements w ith m ineral and petroleum explo rers in the Officer Basin and the Gawler Craton. -

GRADUATION CEREMONIES 2017 Acknowledgement of Country Unisa Respects the Kaurna, Boandik and Barngarla Peoples’ Spiritual Relationship with Their Country

GRADUATION CEREMONIES 2017 Acknowledgement of Country UniSA respects the Kaurna, Boandik and Barngarla peoples’ spiritual relationship with their country. We also acknowledge the diversity of Aboriginal peoples, past and present. Artist: Find out more about the University’s commitment Rikurani to reconciliation at unisa.edu.au/RAP Elyshia Lay Nothing 2016. Acrylic on Canvas. Dimensions Variable This booklet exhibits the outstanding work of graduates of the University of South Australia’s School of Art, Architecture and Design. Chancellor’s welcome Today is a time for celebration as you mark both the end and the beginning of exciting parts of your lives. It is also an occasion on which to look forward to the opportunities available to you as a graduate of the University of South Australia. I am honoured to be able to share this special event with you, and your family and friends. During your time with the University of South Australia you have developed a set of distinctive qualities which describe the knowledge, skills and personal abilities that you will need as you move into a constantly changing global economy. You have acquired an international outlook; a capacity for critical thought and lifelong learning; an ability to communicate effectively and work autonomously and cooperatively; and a sense of social responsibility. You are well equipped to succeed, confident in the knowledge and skills you possess. Congratulations and all the very best as you start the next big adventure in your lives. Mr Jim McDowell Chancellor Mr Jim McDowell LLB (Honours) Mr Jim McDowell is currently Chair of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation and the Air Warfare Destroyer Principals Council. -

Topic 13 –Community Engagement & Nuclear Facilities – Engagement with Aboriginal Communities

PUBLIC SESSION AGENDA TOPIC 13 –COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT & NUCLEAR FACILITIES – ENGAGEMENT WITH ABORIGINAL COMMUNITIES Monday, 16 November 2015 Conference Room, Nuclear Fuel Cycle Royal Commission Level 5, 50 Grenfell Street, Adelaide SA 5000 Mr Keith Thomas, South Australian Native Title Service (SANTS) (12.30pm) Mr Thomas is the CEO of SANTS, the native title service provider for South Australia. Since its establishment in 2008, SANTS has focused on delivering a range of services to secure sustainable social, cultural and economic outcomes for Aboriginal people, including the recognition of native title rights and interests. SANTS aims to work towards such outcomes by working cooperatively with all stakeholders, including through the negotiation of Indigenous Land Use Agreements and Consent Determinations and the facilitation of projects and partnerships. Mr Andrew Collett AM, Counsel for Maralinga Tjarutja & Yalata Community Incorporated (2.15pm) Maralinga Tjarutja is a corporation representing the Traditional Owners in relation to the management, use and control of the Maralinga Tjarutja lands in the far western region of South Australia. Yalata Community Incorporated is an association aimed at promoting the development of the Yalata community and their lands. Both bodies represent the people belonging to the same Western Desert cultural group. Andrew Collett AM is an independent barrister in Adelaide who has provided legal advice to the Maralinga people since 1984. This has included advising and acting for the Maralinga traditional owners in relation to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia 1984 and all matters which arise from it including compensation claims, negotiating with the British and Australian governments over the clean-up of the contaminated lands, the establishment of a compensation trust fund and the hand back of the rehabilitated lands to the traditional owners. -

DIMIA Annual Report 2004-2005

Annual Report Annual 2004–05 DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS AND MULTICULTURAL OF IMMIGRATION DEPARTMENT DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS 2004–05 Annual Report 2004–05 Annual Report DEPARTMENT OF IMMIGRATION AND MULTICULTURAL AND INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS ISSN 1448-8191 ISBN 1 920996 001 Published 2005 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth available from the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 2154, Canberra ACT 2601 or by e-mail Cwealthcopyright@fi nance.gov.au. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the: Intellectual Property Branch Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts GPO Box 2154 Canberra ACT 2601 Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs Annual Report Contact Offi cers: Annual Report Co-ordinator Planning and Reporting Section Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs 6 Chan Street Belconnen ACT 2617 Telephone: (02) 6264 1111 Email: annual [email protected] This report is on the Internet: http://www.immi.gov.au iv 2004–05 DIMIA Annual Report Contents PART 1 Overviews 1 Secretary’s review 2 Departmental overview 8 Contents -

Journal and Proceedings of The

JOURNAL AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY O F NEW SOUTH WALES Volume 139 Parts 1 and 2 (Nos 419–420) 2006 ISSN 0035-9173 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY BUILDING H47 UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY, NSW 2006 Issued September 2006 THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF NEW SOUTH WALES OFFICE BEARERS FOR 2006-2007 Patrons His Excellency, Major General Michael Jeffery AC, CVO, MC Governor General of the Commonwealth of Australia. Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir, AC, Governor of New South Wales. President Prof. J. Kelly, BSc Syd, PhD Reading, DSc NSW, FAIP, FInstP Vice Presidents Mr D.A. Craddock, BSc (Eng) NSW, Grad. Cert. Management UWS. Mr J.R. Hardie, BSc Syd, FGS, MACE. Mr C.M. Wilmot two vacancies Hon. Secretary (Gen.) Dr E. Baker PhD ANU, MSc USyd, BSc (Hons), GradDipEd (Distinction UTS), AMusA, MRACI, CChem. Hon. Secretary (Ed.) Prof. P.A. Williams, BA (Hons), PhD Macq. Hon. Treasurer Ms M. Haire Hon. Librarian Ms C. van der Leeuw Councillors Mr A.J. Buttenshaw Mr J. Franklin Prof. H. Hora Dr M. Lake, PhD Syd Ms Jill Rowling BE UTS, MSc Syd A/Prof. W.A. Sewell, MB, BS, BSc Syd, PhD Melb FRCPA Ms R. Stutchbury Southern Highlands Rep. vacant The Society originated in the year 1821 as the Philosophical Society of Australasia. Its main function is the promotion of Science by: publishing results of scientific investigations in its Journal and Proceedings; conducting monthly meetings; organising summer science schools for senior secondary school students; awarding prizes and medals; and by liason with other scientific societies. Special meetings are held for: the Pollock Memorial Lecture in Physics and Mathematics, the Liversidge Research Lecture in Chemistry, the Clarke Memorial Lecture in Geology, Zoology and Botany, and the Poggendorf Lecture in Agricultural Science. -

Sustaining the Western Myall Woodlands : Ecology and Management

tn oïl- tu F rb{; rQr- ã"'l SUSTAINING THE \MESTERN MYALL WOODLANIDS: ECOLOGYAND MANAGBMENT by Carolyn lreland Department of Environmental Science and Rangeland Management The University of Adelaide A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Phi'losophy at The University of Adelaide (Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Resource Management) January 1997 FRONTISPIECE "Myall is the most attractive tree found in the arid country of South Australia...its branches andfoliøge sweep to the ground and the newfoliage...has a silvery grey colour." R.W. Jessup (1951) Soil Conservation Officer, Department of Agriculture, South Australia The Soils, Geolog,, and Vegetation of North-lVestern South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South AvstraliaT4 TABLE OF CONTENTS ll TABLE OF CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS v -vll ABSTRACT viii - xi DECLARATION xii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND 1 1.2 LITERATURE RE\rIEW OF \ilESTERN MYALL AND REI.ATIONSHIPS TO THT'SIS STRUCTURE 7 1.2.1 AUTECOLOGY AND PFIENOLOGY 7 1.2.2 RECRUITMENT 9 1.2.3 LIFE STAGE STRUCTURES t2 1.2.4 TAXONOMY l3 1.3 KEY QUESTIONS, ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES 15 1.4 OUTLINE OF TIIE TIIESIS I7 CHAPTER 2: THE WESTERN MYALL \ryOODLANDS 20 2.1 INTRODUCTION 20 2.2 TITE STT]DY AREA 2l 2.2.1 CLIMATE 23 2.2.1.1Rainfall ¿J 2. 2. I. 2 I'emperaÍure and Sunshine Hours 26 2.2.1.3 Wind 27 2. 2. I. 4 Potential Evaporati ott 27 2.2.2 GEOLOGY, LANDFORMS AND LAND SYSTEMS 27 2.3 DISTRIBUTION OF WESTERN F},tYALL 29 2.3.1 LITERATURE REVIEW 29 2.3.2 THE BROAD SCALE DISTRIBUTION SURVEY JJ 2.4 USING LIFE STAGES IN THE STUDY OF POPULATION STRUCTURES 35 2.4.1 LIFE STAGES OF TFIE WESTERN MYALL 35 CHAPTER 3: THE OCCURRENCE OF RECRUITMENT 39 3.1 INTRODUCTION 39 3.2 THE REGENERATION NICHE 40 3.3 A MODEL OF RECRUITMENT 4l 3.3.I TESTING PART OF TFIE HYPOTFMSIS 43 3.4 THE OCCURRENCE OF RECRUITMENT 45 3.4.1 EPISODIC EVENTS IN THE ARID ZONE 47 3.4. -

COLLETT Andrew, LARKIN Christopher, BROWN Dennis

RESUMED [2.14 pm] 35 COMMISSIONER: Good afternoon. I welcome you back for a continuation of topic 13, Community Engagement and Nuclear Facilities. Counsel assisting. MR JACOBI: The witness, Mr Christopher Larkin is a Kokotha man with 40 over 40 years of experience working in government departments and agencies delivering programs and services for community, housing, health and land management in South Australia; particularly those focused on Aboriginal interests and issues. He has worked closely with Maralinga Tjarutja and Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) communities over many years 45 and he's in the shop on the immediate left. To his right is Mr Dennis Brown. .SA Nuclear 16.11.15 P-1212 Spark and Cannon Mr Brown is the traditional owner of the Maralinga lands and has worked as a project officer for the Maralinga Tjarutja since 1988. He worked closely with Dr Archie Barton AM, the Aboriginal leader of the Maralinga Tjarutja 5 community during negotiations with the Commonwealth and state governments relating to the contamination and rehabilitation of land from the British nuclear tests. Along side him is Dr Scott Cane, a consulting anthropologist. Mr Cane has 10 over 35 years of experience working in the field with Aboriginal people around Australia. During the 1980s, Dr Cane performed anthropological work with the communities affected by the British nuclear tests at Maralinga. He assisted Maralinga Tjarutja during negotiations with the Commonwealth and state governments regarding the clean-up, compensation and establishment of the 15 trust fund to administer the compensation. Mr Patrick Davoren has, since the 1970s, held a number of positions in the Commonwealth government departments advising on nuclear-related issues and strategies. -

Social Justice Report 2005

Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Recent publications of the Human Rights Social Justice Commissioner and Equal Opportunity Commission REPORTS n Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Annual Report 2004-05 The position of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner was established n Striking the Balance: Women, men, work and family Discussion Paper within the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission in 1993 to carry out the following n Federal Discrimination Law 2005 (Sex Discrimination Commissioner) functions: n Social Justice Report 2004 (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner) (1) Report annually on the enjoyment and exercise of human rights by Aboriginal peoples n Native Title Report 2004 (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner) and Torres Strait Islanders, and recommend where necessary on the action that should n Voices of Australia: 30 Years of the Racial Discrimination Act (Race Discrimination Commissioner) be taken to ensure these rights are observed. n Face the Facts – Countering myths about Refugees, Migrants and Indigenous People (2005) (Race Discrimination Commissioner) (2) Promote awareness and discussion of human rights in relation to Aboriginal peoples n Interim Report of the national inquiry into Employment and disability, entitled ‘WORKability: and Torres Strait Islanders. people with disability in the open workplace’ (2005) (Disability Discrimination Commissioner) (3) Undertake research and educational programs for the purposes of promoting respect n Not for Service: Experiences of Injustice and Despair in Mental Health Care in Australia – A report for, and enjoyment and exercise of, human rights by Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait of the consultations by the Mental Health Council of Australia and the Brain and Mind Institute in association with the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (2005) Islanders.