California's Oranges and BC's Apples?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

MALCOLM ISLAND ADVISORY COMMISSION (MIAC) Meeting Notes August 26, 2019 Old Medical Building, 270 1St Street, Sointula, BC

MALCOLM ISLAND ADVISORY COMMISSION (MIAC) Meeting Notes August 26, 2019 Old Medical Building, 270 1st Street, Sointula, BC PRESENT: Sandra Daniels, RDMW Electoral “A” Director Carmen Burrows, Sheila Roote, Joy Davidson, Dennis Swanson, Michelle Pottage, Roger Lanqvist ABSENT: Chris Chateauvert, Guy Carlson Patrick Donaghy - Manager of Operations Jeff Long - Manager of Planning & Development Services PUBLIC: None CALL TO ORDER Chair Carmen Burrows called the meeting to order at 7:18 PM. MIAC ADOPTION OF AGENDA 2019/08/26 Motion 1: Agenda 1. Agenda for the August 26, 2019 MIAC meeting. approved Motion that the June 24, 2019 MIAC agenda be approved (with the following additions: ▪ Old Business o Letter of support to BC Ferries in favour of new schedule for the new ferry with an early morning sailing from Sointula to Port McNeill o Zoning ▪ New Business o Rural Islands Economic Forum Nov 7-8, 2019 o Public posting/notices of meeting dates o Mailing address for MIAC o Roads o NWCC (New Way Community Caring) M.S. Carried MIAC 2019/08/26 Motion 2: ADOPTION OF July 29, 2019 MINUTES Minutes approved M.S. Carried PUBLIC DELEGATIONS: None Regional District of Mount Waddington 1 Minutes of the MIAC Meeting OLD BUSINESS: - Community knotweed meeting: o Date is yet to be set, awaiting confirmation from Patrick regarding availability of staff/contractors for meeting – September - BC Ferries letter. o Dennis provided a draft of a letter to BC Ferries expressing the MIAC supporting a revised schedule for the new ferry. The revised schedule would include an early morning ferry sailing to Port McNeill leaving shortly after 7 AM. -

BURT FEINTUCH Folk Music Is a Social Phenomenon.1 It Exists Within the Contexts of Certain Patterns of Human Interaction

SOINTULA, BRITISH COLUMBIA: Aspects of a Folk Music Tradition as a Social Phenomenon BURT FEINTUCH Folk music is a social phenomenon.1 It exists within the contexts of certain patterns of human interaction. When we speak of a “tradition,” in the sense of “the folk music tradition,” we refer to a patterned social phenomenon in which utilization of a class of folkloric items occurs. A tradition is not composed of a repertoire, nor does it reside in individuals. Just as a traffic pattern is not dependent upon specific drivers, a folkloric tradition is social rather than individual.2 We have a large number of studies of the content of repertoires (item-oriented studies) and a number of studies which focus on the individual performer or repertoire-bearer (person-oriented studies), but we have little information concerning the social nature of a tradition. The following is an attempt to portray in a general sense a vital tradition of folk music in a small fishing community in British Columbia.3 Sointula, British Columbia, is a community of approximately five hundred people, about half of them first, second, or third generation Finnish-Canadians. The community is located on Malcolm Island, a small island about twelve miles long by an average of two miles wide, located in the Queen Charlotte Sound, between the northern portion of Vancouver Island and the mainland, about 185 air miles north of Vancouver. Although the earliest group to settle Malcolm Island was an English and Irish religious sect intending to establish a Christian utopian society, the first group to settle the island and remain for a significant length of time was a group of Finnish utopian socialists.4 The first substantial Finnish migration to British Columbia was com prised of laborers who arrived with construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. -

Review of Coastal Ferry Services

CONNECTING COASTAL COMMUNITIES Review of Coastal Ferry Services Blair Redlin | Special Advisor June 30, 2018 ! !! PAGE | 1 ! June 30, 2018 Honourable Claire Trevena Minister of Transportation and Infrastructure Parliament Buildings Victoria BC V8W 9E2 Dear Minister Trevena: I am pleased to present the final report of the 2018 Coastal Ferry Services Review. The report considers the matters set out in the Terms of Reference released December 15, 2017, and provides a number of recommendations. I hope the report is of assistance as the provincial government considers the future of the vital coastal ferry system. Sincerely, Blair Redlin Special Advisor ! TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 3! 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9! 1.1| TERMS OF REFERENCE ...................................................................................................................................................... 10! 1.2| APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 12! 2 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Hard Work Conquers All Building the Finnish Community in Canada

Hard Work Conquers All Building the Finnish Community in Canada Edited by Michel S. Beaulieu, David K. Ratz, and Ronald N. Harpelle Sample Material © UBC Press 2018 © UBC Press 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Hard work conquers all : building the Finnish community in Canada / edited by Michel S. Beaulieu, David K. Ratz, and Ronald N. Harpelle. Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-7748-3468-1 (hardcover). – ISBN 978-0-7748-3470-4 (PDF). – ISBN 978-0-7748-3471-1 (EPUB). – ISBN 978-0-7748-3472-8 (Kindle) 1. Finnish Canadians. 2. Finns – Canada. 3. Finnish Canadians – Social conditions – 20th century. 4. Finns – Canada – Social conditions – 20th century. 5. Finnish Canadians – Economic conditions – 20th century. 6. Finns – Canada – Economic conditions – 20th century. 7. Finnish Canadians – Social life and customs – 20th century. 8. Finns – Canada – Social life and customs – 20th century. I. Beaulieu, Michel S., editor II. Ratz, David K. (David Karl), editor III. Harpelle, Ronald N., editor FC106.F5H37 2018 971’.00494541 C2017-903769-2 C2017-903770-6 UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada (through the Canada Book Fund), the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. Set in Helvetica Condensed and Minion by Artegraphica Design Co. Ltd. Copy editor: Robyn So Proofreader: Carmen Tiampo Indexer: Sergey Lobachev Cover designer: Martyn Schmoll Cover photos: front, Finnish lumber workers at Intola, ON, ca. -

Travelling to Sointula

Travelling to Sointula The isolated village of Sointula (Finnish for “Place of Harmony”) was founded in 1901 by a group of Finnish settlers on Malcolm Island in BC. Sointula lies between Vancouver Island and the BC mainland, northeast of Port McNeill and not far from Alert Bay. Sointula is a 25 minute ferry ride from Port McNeill. Travel directions outlined are mainly Vancouver Island based - from Victoria or Nanaimo to Port McNeill. Travel by Car Vancouver Island’s Highway 19 runs from Victoria to Port Hardy. The stretch of Highway 19 that extends from Campbell River to Port McNeill is a well maintained, paved, double lane highway with frequent wildlife sightings. Approximate driving distances times are: Victoria to Port McNeill, 460 km, 5 ½-6 hours Nanaimo to Port McNeill, 340 km, 4 hours Road Conditions: www.drivebc.com or 1-800-550-4997 SointulaTravel.docx Page 1 of 2 Travel by Air Pacific Coastal Airlines operate daily scheduled flights between the Port Hardy Airport (YZT) and Vancouver Airport’s South Terminal (YVR) with approximately one hour flying time. These flights leave from a smaller, adjacent airport in Vancouver called the South Terminal. A shuttle bus service runs frequently between Vancouver Main Terminal and the South Terminal. Pacific Coastal Airlines: www.pacific-coastal.com or 1-800-663-2872 or 604-273-8666. WestJet has flights to Vancouver (YVR), Victoria (YYJ), Nanaimo (YCD) and Comox (YQQ). WestJet: www.westjet.com or 1-888-937-8538 (1-888-WESTJET) Air Canada has flights to Vancouver (YVR), Victoria (YYJ), Nanaimo (YCD) and Comox (YQQ). -

BC Ferries' Submission

British Columbia Ferry Services Inc. Performance Term Three Submission to the British Columbia Ferries Commissioner September 30, 2010 This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 1 PART I – CORE INFORMATION............................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 1: CORE FERRY SERVICES............................................................................................................. 3 SECTION 2: TARIFFS FOR CORE FERRY SERVICES........................................................................................ 3 SECTION 3: SERVICE FEES ........................................................................................................................... 3 SECTION 4: REVENUES FROM ALL OTHER SOURCES.................................................................................... 4 SECTION 5: EXPENSES ................................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 6: ALTERNATIVE SERVICE PROVIDERS ......................................................................................... 4 PART II – OTHER INFORMATION ........................................................................................................ 5 SECTION 7: CAPITAL EXPENDITURES ......................................................................................................... -

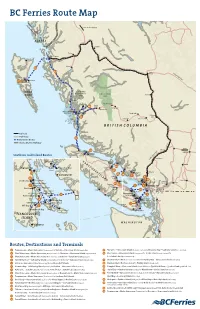

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver -

Rising Tide Fall 2011

rising tide . l i v i n g o c e a n s . o r g i e s . w w w H e a l t h y O c e a n s . H e a l t h y C o m m u n i t FALL 2011 Salmon Farms t he shocking news that 141 California sea lions were deliberately shot by Issued salmon farmers during the first three months of 2011 is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to recent revelations of the environmental damage caused by the net-cage industry in B.C. Now that Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has responded to our demands for more transparent reporting on the impacts of salmon farms, we are beginning to get a much clearer picture of the harm that open net-cages are inflicting on coastal ecosystems. Living Oceans Society, as a member of the Coastal Alliance for Aquaculture Reform (CAAR), has long advocated for more transparency around activities at B.C. salmon farms. Neither the government nor the salmon farming industry have willingly supplied information about disease outbreaks, drug treatments or marine mammal deaths in the past. That’s why we pushed hard for better public reporting of site-by-site impacts in talks with DFO Two Steller sea lions, a species listed under the federal Species at Risk Act as they drafted new salmon farming regulations in (SARA) as ‘of special concern’, were shot by Mainstream at their West Side preparation for the transfer of jurisdiction from the farm in the Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve Province of B.C. -

Environment and Economy in the Finnish-Canadian Settlement of Sointula

Utopians and Utilitarians: Environment and Economy in the Finnish-Canadian Settlement of Sointula M IKKO SAIKKU There – where virgin nature, unaltered by human hand, exudes its own, mysterious life – we shall find the sweet feeling that terrifies a corrupt human being, but makes a virtuous one sing with poetic joy. There, amidst nature, we shall find ourselves and feel the craving for love, justice, and harmony. Matti Kurikka, 19031 he history of Sointula in British Columbia – the name of the community is a Finnish word roughly translatable as “a place of harmony” – provides ample material for an entertaining T 1901 narrative. The settlement was founded in as a Finnish utopian commune on the remote Malcolm Island in Queen Charlotte Strait. Al- though maybe a quarter of Malcolm Island’s eight hundred inhabitants are still of Finnish descent, little Finnish is spoken in the community today.2 Between the 1900s and the 1960s, however, the predominant language of communication in Sointula was Finnish. The essentials of Sointula’s fascinating history are rather well known: they include the establishment of an ethnically homogenous, utopian socialist commune; its inevitable breakup; strong socialist and co-operative 1 I wish to thank Pirkko Hautamäki, Markku Henriksson, Kevin Wilson, the editor of BC Studies, and two anonymous readers for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript. A 2004 travel grant from the Chancellor’s Office at the University of Helsinki and a 2005 Foreign Affairs Canada Faculty Research Award enabled me to conduct research in British Columbia. Tom Roper, Gloria Williams, and other staff at the Sointula Museum were most supportive of my research on Malcolm Island, while Jim Kilbourne and Randy Williams kindly provided me with the hands-on experience of trolling for Pacific salmon onboard the Chase River. -

Mt Waddington

Vancouver Island, BC Vancouver Island’s North Coast The locations may be remote, but the possibilities are not! Small, friendly and Affordable Communities Do you enjoy being surrounded by magnificent scenery and outdoor recreation? Consider the joy of working in a close‐ knit, small‐town community setting and the important role healthcare providers’ play in these communities. We offer the best possible life-work balance with community focused teams, relocation assistance and an amazing lifestyle in one of Canada’s best climates. Rehabilitation Roles - Unique Opportunities in a Challenging Environment Living and working in remote northern locations is not without it challenges but the rewards are enormous. You will work closely with the First Nations communities in places few visitors ever get to see. Commute by Air - We have a special primary care team that flies into Kingcome and Gilford by helicopter every two weeks. The team is made up of physician and primary health care nurse who go in every trip. Based on needs and referrals, this team will also include an occupational therapist, physiotherapist, diabetes educator, dietician or mental health and addictions workers. Zeballos and Kyuquot are based on referrals and travel is either by road or by helicopter once a month when the physician flies in. Each of these two communities has a nursing station run by Island Health. Distinctive Rehabilitation Teams – In Mount Waddington, our rehabilitation team incorporates a physiotherapist, occupational therapist and a rehabilitation assistant. New graduates receive practice support and mentorship from our experienced staff. Additional support for the community resource team comes from the rehabilitation teams in Campbell River. -

Zone 9: Choices for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities

AFFORDABLE HOUSING Choices for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities Zone 9 - Vancouver Island North and Nanaimo The Housing Listings is a resource directory of affordable housing in British Columbia and divides British Columbia into 12 zones. Zone 9 identifies affordable housing in Vancouver Island North and Nanaimo. The attached listings are divided into two sections. Section #1: Apply to The Housing Registry Section 1 - Lists developments that The Housing Registry accepts applications for. These developments are either managed by BC Housing, Non-Profit societies, or Co- Operatives. To apply for these developments, please complete an application form which is available from any BC Housing office, or download the form from www.bchousing.org/housing- assistance/rental-housing/subsidized-housing. Section #2: Apply directly to Non-Profit Societies and Housing Co-ops Section 2 - Lists developments managed by non-profit societies or co-operatives which maintain and fill vacancies from their own applicant lists. To apply for these developments, please contact the society or co-op using the information provided under "To Apply". Please note, some non-profits and co-ops close their applicant list if they reach a maximum number of applicants. In order to increase your chances of obtaining housing it is recommended that you apply for several locations at once. Housing for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities, Zone 9 - Vancouver Island North and Nanaimo August 2021 AFFORDABLE HOUSING SectionSection 1:1: ApplyApply toto TheThe HousingHousing RegistryRegistry forfor developmentsdevelopments inin thisthis section.section. Apply by calling 250-475-7550 or, if calling outside Victoria, call toll free at 1-800-787-2807 and press 4.