Hard Work Conquers All Building the Finnish Community in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A C C E P T E

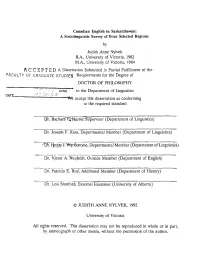

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

Precious Legacy. . Finnish-Canadian Archives, 1882-1

"Kallista Perintoa - Precious Legacy.p. Finnish-Canadian Archives, 1882-1985 by EDWARD W. LAINE* The contours of the Canadian archival establishment have been traditionally defined by the upper strata of Canadian society. In other words, those public and private archives sponsored by the Canadian elite have become captive to the interests of their particular benefactors. Symptomatic of this has been the Canadian archival establishment's constant emphasis on the jurisdictional insularity of its member institutions and its lack of historical consciousness of a common archival heritage as well as its striking indifference to the communal memory and public service. The prevailing archival tradition in this country - if such exists - is elitist rather than popular and democratic in nature. Yet, as the history of Finnish-Canadian archival activity indicates, this country also has other, more popular archival traditions which developed outside the pale of the Canadian archival establishment and its ranks of professional archivists. From the time they trickled into Canada in the 1880s, the immigrant Finns brought with them a well-defined aware- ness of a native Finnish archival tradition, one which can be traced back at least to the fifteenth century. In addition, they had an acute sense of self-identity as a people and, as well, a remarkable degree of historical consciousness concerning their past and present in both individual and communal terms, elements of which were to become further accen- tuated in the course of their settlement here. They also possessed a high rate of literacy and great respect for the written word. Finally, they had great desire and capacity for organization - especially in the matter of providing themselves with those community services that were non-existent in the "new land" and which they deemed to be essential for their commonweal. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

MALCOLM ISLAND ADVISORY COMMISSION (MIAC) Meeting Notes August 26, 2019 Old Medical Building, 270 1St Street, Sointula, BC

MALCOLM ISLAND ADVISORY COMMISSION (MIAC) Meeting Notes August 26, 2019 Old Medical Building, 270 1st Street, Sointula, BC PRESENT: Sandra Daniels, RDMW Electoral “A” Director Carmen Burrows, Sheila Roote, Joy Davidson, Dennis Swanson, Michelle Pottage, Roger Lanqvist ABSENT: Chris Chateauvert, Guy Carlson Patrick Donaghy - Manager of Operations Jeff Long - Manager of Planning & Development Services PUBLIC: None CALL TO ORDER Chair Carmen Burrows called the meeting to order at 7:18 PM. MIAC ADOPTION OF AGENDA 2019/08/26 Motion 1: Agenda 1. Agenda for the August 26, 2019 MIAC meeting. approved Motion that the June 24, 2019 MIAC agenda be approved (with the following additions: ▪ Old Business o Letter of support to BC Ferries in favour of new schedule for the new ferry with an early morning sailing from Sointula to Port McNeill o Zoning ▪ New Business o Rural Islands Economic Forum Nov 7-8, 2019 o Public posting/notices of meeting dates o Mailing address for MIAC o Roads o NWCC (New Way Community Caring) M.S. Carried MIAC 2019/08/26 Motion 2: ADOPTION OF July 29, 2019 MINUTES Minutes approved M.S. Carried PUBLIC DELEGATIONS: None Regional District of Mount Waddington 1 Minutes of the MIAC Meeting OLD BUSINESS: - Community knotweed meeting: o Date is yet to be set, awaiting confirmation from Patrick regarding availability of staff/contractors for meeting – September - BC Ferries letter. o Dennis provided a draft of a letter to BC Ferries expressing the MIAC supporting a revised schedule for the new ferry. The revised schedule would include an early morning ferry sailing to Port McNeill leaving shortly after 7 AM. -

REVIEW ARTICLES 225 Review Articles

REVIEW ARTICLES 225 Review Articles The trouble with people IS not that they don't know but that they know so much that aln't so. Henry Wheeler Shaw In h~sJosh B~llrngs' Encldopedra of WI~and W~rdorn(1874) The Strait-jacketing of Multiculturalism in Canada by EDWARDW. LAINE 'Dangerous Foreigners': European Immigrant Workers and Labour Radicalism in Canada,1896- 1932. DONALD AVERY. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1979. 204 p. ISBN 0 7710 OR26 0 pa. $6.95. (Included as a volume in the publishers' The Cunadian Sucial Hisrorjl Series.) If the grim necessities of realpolitik in the early 1970s had finally forced the federal gov- ernment to recognize the fundamental presence of cultural pluralism in Canada for the sake of national unity, they were also instrumental in establishing the outer limits for the expression of this ethno-cultural diversity under the rubric of "multiculturalism within a bilingual framework".' In other words. the main thrust of the government's multicultural policy was to reaffirm the Official Languages Act of 1969 whichaccorded de,iurestatus to I House of Commons, Debates. 28th Purliamenr. Vol Vlll (Ottawa, 1971), p. 8545. in which the then Prime Minister of Canada noted during the course of his announcement on the government's implementation of this policy on 8 October 1971: "A policy of multiculturalism within a bilingual framework commends itself to the government as the most suitable means of assuring the cultural freedom of Canadians. Such a policy should help break down discriminatory attitudes and cultural jealousies. National unity if it is to mean anything in the deeply personal sense must be founded on confidence in one's own individual identity; out of this can grow respect for that of others and a willingness to share ideas, attitudes and assumptions. -

Minutes of the Hoito Restaurant March 27, 1918 to May 2, 1920

Minutes of the Hoito Restaurant March 27, 1918 to May 2, 1920 Translated and Introduced by Saku Pinta This work is dedicated to the staff of the Hoito Restaurant, past, present, and future. 2 The Origins of the Hoito Restaurant: A History from Below By Saku Pinta Then Slim headed to Bay Street, where he read a sign upon a door Inviting the world workers up onto the second floor Come right in Fellow Worker, hang your crown upon the wall And eat at the Wobbly restaurant, you'll pay no profits there at all - “The Second Coming of Christ” by Pork-Chop Slim1 In continuous operation in the same location for over 100 years, the Hoito Restaurant has served Finnish and Canadian food in the city of Thunder Bay, Ontario while also serving as an important local landmark and gathering place. The restaurant the New York Times called “arguably Canada's most famous pancake house” has, since it opened on May 1, 1918, occupied the bottom-floor of the 109-year old Finnish Labour Temple on 314 Bay Street – a building formally recognized as a National Historic Site of Canada in 2011.2 In recognition of the centenary of the founding of the Hoito Restaurant the Thunder Bay Finnish Canadian Historical Society is proud to publish, for the first time in English-language translation, the entirety of the restaurant's first minute book. This unique and historically significant primary source document begins on March 27, 1918, with the first meeting to discuss the establishment of the restaurant, and concludes over two years later on May 2, 1920. -

BURT FEINTUCH Folk Music Is a Social Phenomenon.1 It Exists Within the Contexts of Certain Patterns of Human Interaction

SOINTULA, BRITISH COLUMBIA: Aspects of a Folk Music Tradition as a Social Phenomenon BURT FEINTUCH Folk music is a social phenomenon.1 It exists within the contexts of certain patterns of human interaction. When we speak of a “tradition,” in the sense of “the folk music tradition,” we refer to a patterned social phenomenon in which utilization of a class of folkloric items occurs. A tradition is not composed of a repertoire, nor does it reside in individuals. Just as a traffic pattern is not dependent upon specific drivers, a folkloric tradition is social rather than individual.2 We have a large number of studies of the content of repertoires (item-oriented studies) and a number of studies which focus on the individual performer or repertoire-bearer (person-oriented studies), but we have little information concerning the social nature of a tradition. The following is an attempt to portray in a general sense a vital tradition of folk music in a small fishing community in British Columbia.3 Sointula, British Columbia, is a community of approximately five hundred people, about half of them first, second, or third generation Finnish-Canadians. The community is located on Malcolm Island, a small island about twelve miles long by an average of two miles wide, located in the Queen Charlotte Sound, between the northern portion of Vancouver Island and the mainland, about 185 air miles north of Vancouver. Although the earliest group to settle Malcolm Island was an English and Irish religious sect intending to establish a Christian utopian society, the first group to settle the island and remain for a significant length of time was a group of Finnish utopian socialists.4 The first substantial Finnish migration to British Columbia was com prised of laborers who arrived with construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. -

Finnish Studies

Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 23 Number 1 November 2019 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-7328298-1-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458, Box 2146, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hilary-Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Tim Frandy, Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University Daniel Grimley, Professor, Oxford University Titus Hjelm, Associate Professor, University of Helsinki Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Johanna Laakso, Professor, University of Vienna Jason Lavery, Professor, Oklahoma State University James P. Leary, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, University of Helsinki Jussi Nuorteva, Director General, The National Archives of Finland Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury Beth L. -

Review of Coastal Ferry Services

CONNECTING COASTAL COMMUNITIES Review of Coastal Ferry Services Blair Redlin | Special Advisor June 30, 2018 ! !! PAGE | 1 ! June 30, 2018 Honourable Claire Trevena Minister of Transportation and Infrastructure Parliament Buildings Victoria BC V8W 9E2 Dear Minister Trevena: I am pleased to present the final report of the 2018 Coastal Ferry Services Review. The report considers the matters set out in the Terms of Reference released December 15, 2017, and provides a number of recommendations. I hope the report is of assistance as the provincial government considers the future of the vital coastal ferry system. Sincerely, Blair Redlin Special Advisor ! TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 3! 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9! 1.1| TERMS OF REFERENCE ...................................................................................................................................................... 10! 1.2| APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 12! 2 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................. -

The Historical Archaeology of Finnish Cemeteries in Saskatchewan

In Silence We Remember: The Historical Archaeology of Finnish Cemeteries in Saskatchewan A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By Verna Elinor Gallén © Copyright Verna Elinor Gallén, June 2012. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying, publication, or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Department Head Department of Archaeology and Anthropology 55 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B1 i ABSTRACT Above-ground archaeological techniques are used to study six Finnish cemeteries in Saskatchewan as a material record of the way that Finnish immigrants saw themselves – individually, collectively, and within the larger society. -

California's Oranges and BC's Apples?

California’s Oranges and B.C.’s Apples? Lessons for B.C. from California Groundwater Reform Randy Christensen and Oliver M. Brandes Randy Christensen is a lawyer with a focus on water law and policy, who is qualified to practice in the United States and Canada. He has been a lawyer with Ecojustice Canada (formerly the Sierra Legal Defence Fund) for nearly 15 years and served as managing lawyer for its Vancouver office for several years. Randy has been lead counsel in numerous cases in Canadian courts. He has also made many appearances before administrative and international tribunals. Randy served as a member of the Canadian Delegation to the United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development from 2007 to 2010. He began working with the POLIS Water Sustainability Project in 2012 as a research associate with a focus on water law. Oliver M. Brandes is an economist and lawyer by training and a trans-disciplinarian by design. He serves as co-director of the POLIS Project on Ecological Governance at the University of Victoria’s Centre for Global Studies and leads the award-winning POLIS Water Sustainability Project, where his work focuses on water sustainability, sound resource management, public policy development, and ecologically based legal and institutional reform. Oliver is an adjunct professor at both the University of Victoria’s Faculty of Law and School of Public Administration. He serves as an advisor to numerous national and provincial NGOs, as well as governments at all levels regarding watershed governance and water law reform. This has included serving as a technical advisor to the B.C. -

Challenges and Opportunities for the Internationalisation of Finnish Sme's

Bachelor's thesis International Business International Business Management 2013 Jukka Hyvönen CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE INTERNATIONALISATION OF FINNISH SME’S TO CANADA – Perspective of Finpro and similar internationalisation support organisations BACHELOR´S THESIS | ABSTRACT TURKU UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES International Business | International Business Management 2013| 58 Instructor: Ajaya Joshi Jukka Hyvönen CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE INTERNATIONALISATION OF FINNISH SME’S TO CANADA Internationalisation and moving to a new market is always a challenge, especially during the on- going challenging economic climate. However, Finland is a small market and in order to grow and become successful internationally small and medium sized companies must take the risk to seek the necessary growth abroad. Distant and unknown markets such as Canada tend to get less attention from the expanding company, so little that even the most visible business opportunities might get unexploited. During my time as a Market Analyst Intern at the Finpro, Finland Trade Center office in Toronto, Canada in 2011 I learned about the challenges and opportunities of the Canadian market. This thesis, based on authors experience during the internship, public online sources as well as an interview of the Finpro country representative and my former boss, Mr Ari Elo will introduce the most potential industries as well as study and analyse those obstacles and unused opportunities of this market from the viewpoint of Finnish expertise and specialization. The research reveals that there are major unused opportunities and demand for Finnish expertise in Cleantech and Arctic technologies. Main reason for not exploiting the opportunities are simply lack of knowledge and reluctance to move to a geographically distant market, especially when Finland’s foreign trade representative services are allocated very few resources, relying on volunteers.