Restorying Settler Imaginaries By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1992 Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier Randy William Widds University of Regina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Widds, Randy William, "Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier" (1992). Great Plains Quarterly. 649. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/649 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SASKATCHEWAN BOUND MIGRATION TO A NEW CANADIAN FRONTIER RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS Almost forty years ago, Roland Berthoff used Europeans resident in the United States. Yet the published census to construct a map of En despite these numbers, there has been little de glish Canadian settlement in the United States tailed examination of this and other intracon for the year 1900 (Map 1).1 Migration among tinental movements, as scholars have been this group was generally short distance in na frustrated by their inability to operate beyond ture, yet a closer examination of Berthoff's map the narrowly defined geographical and temporal reveals that considerable numbers of migrants boundaries determined by sources -

A C C E P T E

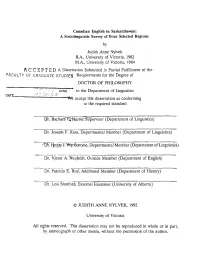

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

A THREAT to LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King

S. Peter Regenstreif A THREAT TO LEADERSHIP: C.A.Dunning and Mackenzie King BY Now mE STORY of the Progressive revolt and its impact on the Canadian national party system during the 1920's is well documented and known. Various studies, from the pioneering effort of W. L. Morton1 over a decade ago to the second volume of the Mackenzie King official biography2 which has recently appeared, have dealt intensively with the social and economic bases of the movement, the attitudes of its leaders to the institutions and practices of national politics, and the behaviour of its representatives once they arrived in Ottawa. Particularly in biographical analyses, 3 a great deal of attention has also been given to the response of the established leaders and parties to this disrupting influence. It is clearly accepted that the roots of the subsequent multi-party situation in Canada can be traced directly to a specific strain of thought and action underlying the Progressivism of that era. At another level, however, the abatement of the Pro~ gressive tide and the manner of its dispersal by the end of the twenties form the basis for an important piece of Canadian political lore: it is the conventional wisdom that, in his masterful handling of the Progressives, Mackenzie King knew exactly where he was going and that, at all times, matters were under his complete control, much as if the other actors in the play were mere marionettes with King the manipu lator. His official biographers have demonstrated just how illusory this conception is and there is little to be added to their efforts on this score. -

The Canadian Bar Review

THE CANADIAN BAR REVIEW THE CANADIAN BAR REVIEW is the organ of the Canadian Bar Association, and it is felt that its pages should be open to free and fair discussion of all matters of interest to the legal profession in Canada. The Editor, however, wishes it to be understood that opinions expressed in signed articles are those of the individual writers only, and that the REVIEW does not assume any responsibility for them. It is hoped that members of the profession will favour the Editor from time to time with notes of important cases determined by the Courts in which they practise. Contributors' manuscripts must be typed before being sent to the Editor at the Exchequer Court Building, Ottawa . TOPICS OF THE MONTH. ACADEMIC HONOURS FOR THE PRESIDENT OF THE C.B .A. -Our readers will be interested to learn that at a Convocation of Queen's University, held on the 12th of last month, Sir James Aikins, K.C ., President of the Canadian Bar Association, received the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws . Sir Robert Borden, K.C ., Chancellor of the University, presided at the Convocation . At the same time simi- lar degrees were conferred upon His Excellency the Governor- General of the Dominion and Sir Clifford Sifton . Four other insti- tutions of learning in Canada had preceded Queen's University in paying a tribute to the distinguished place held by Sir James Aikins as a citizen of Canada, namely, the University of Manitoba in 1919, Alberta University and McMaster University in 1921, and Toronto University in 1924 . -

Hard Work Conquers All Building the Finnish Community in Canada

Hard Work Conquers All Building the Finnish Community in Canada Edited by Michel S. Beaulieu, David K. Ratz, and Ronald N. Harpelle Sample Material © UBC Press 2018 © UBC Press 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Hard work conquers all : building the Finnish community in Canada / edited by Michel S. Beaulieu, David K. Ratz, and Ronald N. Harpelle. Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-0-7748-3468-1 (hardcover). – ISBN 978-0-7748-3470-4 (PDF). – ISBN 978-0-7748-3471-1 (EPUB). – ISBN 978-0-7748-3472-8 (Kindle) 1. Finnish Canadians. 2. Finns – Canada. 3. Finnish Canadians – Social conditions – 20th century. 4. Finns – Canada – Social conditions – 20th century. 5. Finnish Canadians – Economic conditions – 20th century. 6. Finns – Canada – Economic conditions – 20th century. 7. Finnish Canadians – Social life and customs – 20th century. 8. Finns – Canada – Social life and customs – 20th century. I. Beaulieu, Michel S., editor II. Ratz, David K. (David Karl), editor III. Harpelle, Ronald N., editor FC106.F5H37 2018 971’.00494541 C2017-903769-2 C2017-903770-6 UBC Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program of the Government of Canada (through the Canada Book Fund), the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council. Set in Helvetica Condensed and Minion by Artegraphica Design Co. Ltd. Copy editor: Robyn So Proofreader: Carmen Tiampo Indexer: Sergey Lobachev Cover designer: Martyn Schmoll Cover photos: front, Finnish lumber workers at Intola, ON, ca. -

The Men in Sheepskin Coats Tells the Story of the Beginning of Stories About Western Canada in These Countries

THE MEN IN SHEEP S KIN COA ts Online Resource By Myra Junyk © 2010 Curriculum Plus By Myra Junyk Editor: Sylvia Gunnery We acknowledge the financial support of The Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities. Curriculum Plus Publishing Company 100 Armstrong Avenue Georgetown, ON L7G 5S4 Toll free telephone 1-888-566-9730 Toll free fax 1-866-372-7371 E-mail [email protected] www.curriculumplus.ca Background A Summary of the Script Eastern Europe. Writers and speakers were paid to spread exciting The Men in Sheepskin Coats tells the story of the beginning of stories about Western Canada in these countries. Foreign journalists Ukrainian immigration to the Canadian West. Wasyl Eleniak and were brought to Canada so that they could promote the country Ivan Pylypiw, the first “men in sheepskin coats,” came to Canada when they returned home. from the province of Galicia in Ukraine on September 7, 1891. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier and Minister of the Interior Clifford One of the main groups that responded to the advertising campaign Sifton wanted to build a strong Canada by promoting immigration. was the Ukrainians. In 1895, the Ukranians did not have a country Doctor Joseph Oleskiw encouraged Ukrainian farmers such as Ivan of their own. Some of them lived in the provinces of the Austro- Nimchuk and his family to come to Canada. Many other Ukrainians Hungarian Empire while others lived under the Tsar of Russia. Their followed them. rulers spoke other languages and had customs that seemed strange. The small farmers of the province of Galicia in Western Ukraine felt Settlement of the Canadian West crushed by the Polish overlords. -

The Historical Archaeology of Finnish Cemeteries in Saskatchewan

In Silence We Remember: The Historical Archaeology of Finnish Cemeteries in Saskatchewan A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By Verna Elinor Gallén © Copyright Verna Elinor Gallén, June 2012. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying, publication, or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Department Head Department of Archaeology and Anthropology 55 Campus Drive University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B1 i ABSTRACT Above-ground archaeological techniques are used to study six Finnish cemeteries in Saskatchewan as a material record of the way that Finnish immigrants saw themselves – individually, collectively, and within the larger society. -

THE AMERICAN IMPRINT on ALBERTA POLITICS Nelson Wiseman University of Toronto

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Winter 2011 THE AMERICAN IMPRINT ON ALBERTA POLITICS Nelson Wiseman University of Toronto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Wiseman, Nelson, "THE AMERICAN IMPRINT ON ALBERTA POLITICS" (2011). Great Plains Quarterly. 2657. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2657 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE AMERICAN IMPRINT ON ALBERTA POLITICS NELSON WISEMAN Characteristics assigned to America's clas the liberal society in Tocqueville's Democracy sical liberal ideology-rugged individualism, in America: high status was accorded the self market capitalism, egalitarianism in the sense made man, laissez-faire defined the economic of equality of opportunity, and fierce hostility order, and a multiplicity of religious sects com toward centralized federalism and socialism peted in the market for salvation.l Secondary are particularly appropriate for fathoming sources hint at this thesis in their reading of Alberta's political culture. In this article, I the papers of organizations such as the United contend that Alberta's early American settlers Farmers of Alberta (UFA) and Alberta's were pivotal in shaping Alberta's political cul Social Credit Party.2 This article teases out its ture and that Albertans have demonstrated a hypothesis from such secondary sources and particular affinity for American political ideas covers new ground in linking the influence and movements. -

From Wasteland to Utopia: Changing Images of the Canadian in the Nineteeth Century

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1987 From Wasteland to Utopia: Changing Images of the Canadian in the Nineteeth Century R. Douglas Francis University of Calgary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Francis, R. Douglas, "From Wasteland to Utopia: Changing Images of the Canadian in the Nineteeth Century" (1987). Great Plains Quarterly. 424. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/424 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. FROM WASTELAND TO UTOPIA CHANGING IMAGES OF THE CANADIAN WEST IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY R. DOUGLAS FRANCIS It is common knowledge that what one This region, possibly more than any other in perceives is greatly conditioned by what one North America, underwent significant wants or expects to see. Perception is not an changes in popular perception throughout the objective act that occurs independently of the nineteenth century largely because people's observer. One is an active agent in the process views of it were formed before they even saw and brings to one's awareness certain precon the region. 1 Being the last area of North ceived values, or a priori assumptions, that America to be settled, it had already acquired enable one to organize the deluge of objects, an imaginary presence in the public mind. -

The Committee on Lands of the Conservation Commission, Canada, 1909-1921: Romantic Agrarianism in Ontario in an Age of Agricultural Realism Patricia M

Document generated on 10/03/2021 5:18 a.m. Scientia Canadensis Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Revue canadienne d'histoire des sciences, des techniques et de la médecine The Committee on Lands of the Conservation Commission, Canada, 1909-1921: Romantic Agrarianism in Ontario in an Age of Agricultural Realism Patricia M. Bowley Volume 21, Number 50, 1997 Article abstract The Conservation Commission of Canada (CCC) was formed in 1909 as an URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/800404ar advisory body to Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier. It was divided into DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/800404ar eight committees, each of which dealt with the management of a specific natural resource. The Committee on Lands (CL) was composed of members See table of contents who were unable to accept or understand the changes in contemporary agriculture as it moved into the twentieth century. Dr. James Robertson, chair of the CL, was a staunch agrarian romantic, who believed that the most Publisher(s) important attribute of agriculture was the moral, individual and spiritual benefit which it conveyed to the individual. The recommendations and projects CSTHA/AHSTC of the CL were inappropriate and often outdated and redundant. Their endeavours were noted and appreciated by farmers, but their work had no ISSN lasting effect on agriculture in Ontario. The official concept of 'conservation', defined by the CCC, was based on efficient management of Canadian natural 0829-2507 (print) resources, including the soil. In reality, the CL interpreted conservation to 1918-7750 (digital) mean the preservation of a vanishing rural lifestyle. -

A History of Toivola, Michigan by Cynthia Beaudette AALC

A A Karelian Christmas (play) A Place of Hope: A History of Toivola, Michigan By Cynthia Beaudette AALC- Stony Lake Camp, Minnesota AALC- Summer Camps Aalto, Alvar Aapinen, Suomi: College Reference Accordions in the Cutover (field recording album) Adventure Mining Company, Greenland, MI Aged, The Over 80s Aging Ahla, Mervi Aho genealogy Aho, Eric (artist) Aho, Ilma Ruth Aho, Kalevi, composers Aho, William R. Ahola, genealogy Ahola, Sylvester Ahonen Carriage Works (Sue Ahonen), Makinen, Minn. Ahonen Lumber Co., Ironwood, Michigan Ahonen, Derek (playwrite) Ahonen, Tauno Ahtila, Eija- Liisa (filmmaker) Ahtisaan, Martti (politician) Ahtisarri (President of Finland 1994) Ahvenainen, Veikko (Accordionist) AlA- Hiiro, Juho Wallfried (pilot) Ala genealogy Alabama Finns Aland Island, Finland Alanen, Arnold Alanko genealogy Alaska Alatalo genealogy Alava, Eric J. Alcoholism Alku Finnish Home Building Association, New York, N.Y. Allan Line Alston, Michigan Alston-Brighton, Massachusetts Altonen and Bucci Letters Altonen, Chuck Amasa, Michigan American Association for State and Local History, Nashville, TN American Finn Visit American Finnish Tourist Club, Inc. American Flag made by a Finn American Legion, Alfredo Erickson Post No. 186 American Lutheran Publicity Bureau American Pine, Muonio, Finland American Quaker Workers American-Scandinavian Foundation Amerikan Pojat (Finnish Immigrant Brass Band) Amerikan Suomalainen- Muistelee Merikoskea Amerikan Suometar Amerikan Uutiset Amish Ammala genealogy Anderson , John R. genealogy Anderson genealogy -

THE LIPTON JEWISH AGRICULTURAL COLONY 1901-1951 by Theodore H

JEWISH PIONEERS ON CANADA’S PRAIRIES: THE LIPTON JEWISH AGRICULTURAL COLONY 1901-1951 By Theodore H. Friedgut Department of Russian and Slavic Studies Hebrew University of Jerusalem JEWISH PIONEERS ON CANADA’S PRAIRIES: THE LIPTON JEWISH AGRICULTURAL COLONY INTRODUCTION What would bring Jews from the Russian Empire and Rumania, a population that on the whole had long been separated from any agricultural life, to undertake a pioneering farm life on Canada’s prairies? Equally interesting is the question as to what Canada’s interest was in investing in the settlement of Jews, most totally without agricultural experience, in the young Dominion’s western regions? Jewish agricultural settlement in Western Canada was only one of several such projects, and far from the largest. Nevertheless it is an important chapter in the development of the Canadian Jewish community, as well as providing interesting comparative material for the study of Jewish agricultural settlement in Russia (both pre and post revolution), in Argentina, and in the Land of Israel. In this monograph, we present the reader with a detailed exposition and analysis of the political, social, economic and environmental forces that molded the Lipton colony in its fifty-year existence as one of several dozen attempts to plant Jewish agricultural colonies on Canada’s Western prairies. By comparing both the particularities and the common features of Lipton and some other colonies we may be able to strengthen some of the commonly accepted generalizations regarding these colonies, while at the same time marking other assumptions as questionable or even perhaps, mythical.1 In our conclusions we will suggest that after a half century of vibrant cultural, social and economic life, the demise of Lipton and of the Jewish agricultural colonies in general was largely because of the state of Saskatchewan’s agriculture as a chronically depressed industry.