Stratford Festival Composite Script Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

STUDY GUIDE TOOLS for TEACHERS Sponsored By

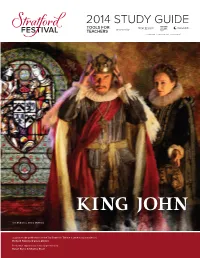

2014 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by Tom McCamus, Seana McKenna Support for the 2014 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre is generously provided by Richard Rooney & Laura Dinner Production support is generously provided by Karon Bales & Charles Beall Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 6 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 7 Sources and Origins .................................................................................................... 8 Stratford Festival Production History ......................................................................... 9 The Production Artistic Team and Cast ............................................................................................... 10 Lesson Plans and Activities Creating Atmosphere .......................................................................................... 11 Mad World, Mad Kings, Mad Composition! ........................................................ 14 Discussion Topics .............................................................................................. -

Uvisno "Acting Is Handed on from Actor to Actor

Inaide the Stratford Festival uviSNO "Acting is handed on from actor to actor. It's the only way to do it... from observing the people who came before you. That is really the way theatre goes" In OFFSTAGE ONSTAGE: Inside the Stratford Festival, Stratford cameras go backstage during an entire season to capture the creative spirit at the heart of a treasured Canadian theatre company. For five decades, the Festival's stage has been home to the world's great plays and performers. Award-winning director John N. Smith (The Boys of St. Vincent), given unprecedented access backstage, offers a fascinating look at the personalities and the production process behind live theatre performance. Peek into William Hutt's dressing room as he does his vocal warm-ups before Twelfth Night. Watch Martha Henry command the stage in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Observe an up-and-coming generation of young performers who learn from the masters. Meet dozens of artists, craftspeople and technicians who reveal their secrets, from shoemaking, sword fighting and sound effects to makeup and mechanical monkeys. Join us behind the scenes of Canada's premier classical theatre institution ... and discover the love for the stage that drives this artistic company. Resource guide on reverse side, DIRECTOR: John N. Smith PRODUCER: Gerry Flahive 83 minutes Order number: C9102 042 Closed captioned. A decoder is required. TO ORDER NFB VIDEOS, CALL TODAY! -800-267-7710 (Canada) 1-800-542-2164 (USA) © 2002 National Film Board of Canada. A licence is required for any reproduction, television broadcast, sale, rental or public screening. -

2016 Study Guide 2016 Study Guide

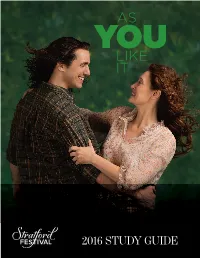

2016 STUDY GUIDE 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER AS YOU LIKE IT BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR JILLIAN KEILEY TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by M. Fainer and by The Harkins/Manning Families In Memory of James & Susan Harkins INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Cyrus Lane, Petrina Bromley. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 7 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................. -

DECEMBER 2, 1993 CONCORDIA's THURSDAY REPORT Open House Showcases Students' Work MITE AVISTA Opens the Doors to the Magic of Media Technology EL E

0 N C 0 R D I A,S SDAY ~PORT Proceeds of concerts, bake sales to help needy students Spreading the spirit around group cooking," he said. ers: a decorated tree in the atrium of BY JENNIFER DALES Both the co-op kitchen and food the J.W. McConnell Building. The voucher programme are supported J\ t Campus Ministry, staff and tree's lights were switched on Tues by the Ministry's annual Spirit of r-lstudents are revving up for day afternoon, and since then, it's Christmas Drive. Peter Cote, its co their busiest season of the year. being decorated with fund-raising ordinator, said the drive raised "Our primary concern is social ribbons. $8,091 last year. action," said Father Bob Nagy in an The Drive's roots date back to 'We have used almost all of the interview at Belmore House, the money," he said. "Well over 200 1914, when a collection was taken up home of Concordia's Campus Min students have used our service." at Loyola College to help the some of istry on the Loyola Campus. The the families affected by W odd War I. annual Spirit of Christmas Drive Calls for donations The first drive, organized in 1974, supports a food-voucher pro Drive organizers sent letters was known as the Christmas Basket gramme for needy students and a requesting donations to depart Drive. It provided food baskets to co-op kitchen. ments throughout the University. needy families in the Montreal_com The food voucher programme To supplement the donations, pro munity and helped students who helps students who are temporarily jects are organized by Concordia were having short-term financial broke. -

2016 Study Guide

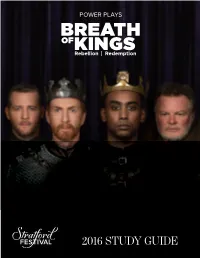

2016 STUDY ProductionGUIDE Sponsor 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER BREATH OF KINGS: REBELLION | REDEMPTION BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE CONCEIVED AND ADAPTED BY GRAHAM ABBEY WORLD PREMIÈRE COMMISSIONED BY THE STRATFORD FESTIVAL DIRECTORS MITCHELL CUSHMAN AND WEYNI MENGESHA TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by The Brian Linehan Charitable Foundation and by Martie & Bob Sachs INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: From left: Graham Abbey, Tom Rooney, Araya Mengesha, Geraint Wyn Davies.. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis .............................................................................................................. -

Three Tall Women: Director’S Notes Four Fortunate Women (And One Man)

PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY SYLVIA D. CHROMINSKA, DR. DESTA LEAVINE IN MEMORY OF PAULINE LEAVINE, SYLVIA SOYKA, THE WESTAWAY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION AND BY JACK WHITESIDE LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

2018-2019 Annual Donor Report Fv.Pages

LOYOLA HIGH SCHOOL FOUNDATION ANNUAL DONOR REPORT 2018-2019 Table of Contents Financial Overview … 3 Loyola by the Numbers … 4 Legacy Giving … 5 2018-2019 Fr. Eric Maclean S.J. Legacy Society Centurion Club … 6 Loyola High School Foundation Board of Directors Leadership Giving … 7 Bursary Endowments Gregory Doyle, Chairman Adopt-A-Student Program … 8 Dario Mazzarello, Vice-Chairman Edmund Piro ‘99, Treasurer … 9 Giving by Level Angelo Noce '84, Secretary Builders’ Guild ($100,000+) Marc Babinski '76, Past Chairman Founders’ Society ($50,000-$99,999) Josephine Battista Men-for-Others Society ($25,000-$49,999) Randy Burns ’86 President’s Circle ($10,000-$24,999) Michael Cross Ignatian Fraternity ($5,000-$9,999) Paul Donovan '82 Loyola Fellowship ($2,500-$4,999) … 10 Patrick Dubee '64 Magis Society ($1,000-$2,499) Michael Lee '82 … 12 Warriors’ League ($500-$999) Tammy Mio … 13 Maroon & White Club ($250-$499) Thomas Park ‘95 1896 Club ($100-$249) … 16 … 19 Sam Ramadori ‘90 Kairos Circle ($1-$99) David Valela ‘91 The Loyola Community at Work … 21 U.S. Friends of Loyola Foundation Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information Board of Directors contained in this report. If you find an error or omission, please contact Maria Carneiro in the Development Office at Terry Fairholm ’72, Chairman 514-486-1101 x224 or [email protected] Robert Beriault ’69 David Bossy ’71 Sean Doyle '83 2 LOYOLA HIGH SCHOOL FOUNDATION ANNUALANNUAL DONOR DONOR REPORT REPORT REPORT 2018-2012015-201 2015-20169 6 Financial Overview TOTAL DONATIONS: $1,397,607 TOTAL DISBURSEMENTS: $1,012,730 July 1, 2018 - June 30, 2019 TOTAL ASSETS: $12,432,000 3 LOYOLA HIGH SCHOOL FOUNDATION ANNUAL DONOR REPORT 2018-2019 LOYOLA BY THE NUMBERS 4 LOYOLA HIGH SCHOOL FOUNDATION ANNUAL DONOR REPORT 2018-2019 This annual report honors the 903 alumni, parents, staff and friends who donated $1,397,607 to the Loyola High School Foundation and the U.S. -

2015 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS for TEACHERS Sponsored By

2015 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by Even Buliung Support for the 2015 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre is generously provided by Corporate Sponsor for the 2015 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Richard Rooney & Laura Dinner Production support is generously provided by M. Vaile Fainer Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 6 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 7 Sources and Origins .................................................................................................... 8 Stratford Festival Production History ....................................................................... 10 The Production Artistic Team and Cast .............................................................................................. 11 Lesson Plans and Activities Pericles’ Travels ................................................................................................... 13 Tapping Into the Story ......................................................................................... -

Stratford Festival Story

2016 STUDY GUIDE 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER MACBETH BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR ANTONI CIMOLINO TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by Jane Petersen Burfield & Family, by Barbara & John Schubert, by the Tremain Family, and by Chip & Barbara Vallis INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Ian Lake. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................... 7 The Historical Macbeth ............................................................................................ -

STUDY GUIDE TOOLS for TEACHERS Sponsored By

2015 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by Mike Shara, Jenna McCutchen (model) Support for the 2015 season of the Festival Theatre is generously provided by Production Sponsor Claire & Daniel Bernstein Production support is generously provided by Larry & Sally Rayner Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 6 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 7 Sources and Origins .................................................................................................... 8 Stratford Festival Production History ......................................................................... 9 The Production Artistic Team and Cast .............................................................................................. 12 Lesson Plans and Activities Story Highlights .................................................................................................... 13 The Cuckoo and the Owl Song: Choral Speaking ............................................... 19 Discussion Topics . ............................................................................................. -

The Festive Remembrance of Shakespeare: a Comparative Study Of

THE FESTIVE REMEMBRANCE OF SHAKESPEARE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE MISSION, IDENTITY, AND RHETORIC OF THREE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE FESTIVALS by Melissa Rynn Porterfield BFA, Long Island University, C.W. Post Campus, 1996 MA, Miami University, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Melissa Rynn Porterfield It was defended on January 14, 2013 and approved by Dr. Bruce McConachie, Academic Rank, Theatre Arts Department Dr. Kathleen George, Academic Rank, Theatre Arts Department Dr. Marianne Novy, Academic Rank, English Department Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Attilio Favorini, Academic Rank, Theatre Arts Department ii Copyright © by Melissa Rynn Porterfield 2013 iii THE FESTIVE REMEBRANCE OF SHAKESPEARE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE MISSION, IDENTITY, AND RHETORIC OF THREE AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE FESTIVALS Melissa Rynn Porterfield, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 ABSTRACT Much has been written over the years on the collective memory of Shakespeare and how it continues to be perpetuated centuries after his death, even in places such as America, to which he had no direct connection. Most recently, the intersection of performance studies and memory studies has afforded theatre historians the opportunity to reevaluate the impact of performance on the collective memory of Shakespeare by acknowledging that the embodied performance of a text is no less important than its written words. This dissertation’s examination of three American Shakespeare companies -- Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Massachusetts, the Three Rivers Shakespeare Festival in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the American Shakespeare Center in Staunton, Virginia -- explores the shifting sands of this intersection.