Shakespeare Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Front Page First Opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, It Was Instantly Heralded As a Classic

SUPPORT FOR THE 2019 SEASON OF THE FESTIVAL THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY DANIEL BERNSTEIN AND CLAIRE FOERSTER PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP 2 DIRECTOR’S NOTES SCAVENGING FOR THE TRUTH BY GRAHAM ABBEY “Were it left to me to decide between a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1787 When The Front Page first opened at the Times Square Theatre on August 14, 1928, it was instantly heralded as a classic. Nearly a century later, this iconic play has retained its place as one of the great American stage comedies of all time. Its lasting legacy stands as a testament to its unique DNA: part farce, part melodrama, with a healthy dose of romance thrown into the mix, The Front Page is at once a veneration and a reproof of the gritty, seductive world of Chicago journalism, firmly embedded in the freewheeling euphoria of the Roaring Twenties. According to playwrights (and former Chicago reporters) Charles MacArthur and Ben Hecht, the play allegedly found its genesis in two real-life events: a practical joke carried out on MacArthur as he was heading west on a train with his fiancée, and the escape and disappearance of the notorious gangster “Terrible” Tommy consuming the conflicted heart of a city O’Conner four days before his scheduled caught in the momentum of progress while execution at the Cook County Jail. celebrating the underdogs who were lost in its wake. O’Conner’s escape proved to be a seminal moment in the history of a city struggling Chicago’s metamorphosis through the to find its identity amidst the social, cultural “twisted twenties” is a paradox in and of and industrial renaissance of the 1920s. -

Shakespeare Othello Mp3, Flac, Wma

Shakespeare Othello mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Non Music / Stage & Screen Album: Othello Country: US Style: Spoken Word MP3 version RAR size: 1178 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1926 mb WMA version RAR size: 1908 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 984 Other Formats: MP1 VOC MP2 WMA MP3 DMF AAC Tracklist A Othello B Othello Companies, etc. Recorded By – F.C.M. Productions Published By – Worlco Credits Composed By [Musique Concrete], Composed By [Sound Patterns] – Desmond Leslie Directed By – Michael Benthall Voice Actor [Brabantio] – Ernest Hare Voice Actor [Cassio] – John Humphry Voice Actor [Desdemona] – Barbara Jefford Voice Actor [Duke Of Venice] – Charles West Voice Actor [Emilia] – Coral Browne Voice Actor [Iago] – Ralph Richardson Voice Actor [Lodovico, Senator] – Joss Ackland Voice Actor [Narrator] – Michael Benthall Voice Actor [Othello] – John Gielgud Voice Actor [Sailor] – Stephen Moore Voice Actor [Senator] – David Tudor-Jones Voice Actor [Small Part] – David Lloyd-Meredith, Peter Ellis , Roger Grainger Written-By – William Shakespeare Notes Modern abridged version. An F.C.M. production. Includes a 16 page booklet. Australian WRC 2nd pressing, sourced from original stampers and featuring unique sleeve art. Same sleeve design as previous issue, except new addresses. The mono version has a red sticker with "mono" on the back (though these tend to drop off with age). "SLS-4" on labels, "LS/4" on sleeve. 299 Flinders Lane Melbourne 177 Elizabeth St Sydney Newspaper House, 93 Queen St Brisbane 60 Pulteney St Adelaide Barnett's Building, Council Ave Perth Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year William Othello (LP, Oldbourne Press, DEOB 3AS DEOB 3AS UK 1964 Shakespeare Album) Odhams Books Ltd. -

Actors and Accents in Shakespearean Performances in Brazil: an Incipient National Theater1

Scripta Uniandrade, v. 15, n. 3 (2017) Revista da Pós-Graduação em Letras – UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil ACTORS AND ACCENTS IN SHAKESPEAREAN PERFORMANCES IN BRAZIL: AN INCIPIENT NATIONAL THEATER1 DRA. LIANA DE CAMARGO LEÃO Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR) Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil ([email protected]) DRA. MAIL MARQUES DE AZEVEDO Centro Universitário Campos de Andrade, UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: The main objective of this work is to sketch a concise panorama of Shakespearean performances in Brazil and their influence on an incipient Brazilian theater. After a historical preamble about the initial prevailing French tradition, it concentrates on the role of João Caetano dos Santos as the hegemonic figure in mid nineteenth-century theatrical pursuits. Caetano’s memorable performances of Othello, his master role, are examined in the theatrical context of his time: parodied by Martins Pena and praised by Machado de Assis. References to European companies touring Brazil, and to the relevance of Paschoal Carlos Magno’s creation of the TEB for a theater with a truly Brazilian accent, lead to final succinct remarks about the twenty-first century scenery. Keywords: Shakespeare. Performances. Brazilian Theater. Artigo recebido em 13 out. 2017. Aceito em 11 nov. 2017. 1 This paper was first presented at the World Shakespeare Congress 2016 of the International Shakespeare Association, in Stratford-upon-Avon. LEÃO, Liana de Camargo; AZEVEDO, Mail Marques de. Actors and accents in Shakespearean performances in Brazil: An incipient national theater. Scripta Uniandrade, v. 15, n. 3 (2017), p. 32-43. Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil Data de edição: 11 dez. -

Colm Feore Essais Et Bonheurs Marie-Claude Fortin

Document generated on 09/28/2021 4:56 a.m. Entre les lignes Le magazine sur le plaisir de lire au Québec Colm Feore Essais et bonheurs Marie-Claude Fortin Traduire Volume 5, Number 2, Winter 2009 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/682ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Les éditions Entre les lignes ISSN 1710-8004 (print) 1923-211X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Fortin, M.-C. (2009). Colm Feore : essais et bonheurs. Entre les lignes, 5(2), 14–17. Tous droits réservés © Les éditions Entre les lignes, 2009 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ ENTRE LES LIGNES Colm Feore Essais et bonheurs Il a incarné tour à tour, et toujours avec autant de talent, Glenn Gould, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Macbeth et le stoïque Martin Ward, le «bon» de Bon Cop, Bad Cop. L'été prochain, à Stratford, Ontario, où il habite, il jouera Cyrano de Bergerac dans une production dirigée par son épouse, Donna Feore. Entre deux épisodes du tournage de la série « 24 », à L.A., et le tour nage à Montréal du film The Trotsky, de Jacos Tierney, Colm Feore nous parle des livres de sa vie. -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

Bruce Greenwood, Leslie Hope, Benjamin Ayres

Directed by Jerry Ciccoritti Written by Jeff Kober Starring: Bruce Greenwood, Leslie Hope, Benjamin Ayres, Megan Follows, David Hewlett, Kris Holden-Reid, Jeff Kober, Grace Lynn Kung, Kristin Lehman, Daniel Maslany, Tony Nappo, Paula Rivera TRT: 92:26 Format: 2:39 Sound: 5.1 surround sound Rating: (pending) Country: Canada Language: English Genre: Drama Trailers: Available Website: www.IndicanPictures.com Table of Contents Synopsis ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Director’s Statement .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Producer’s Statement ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Artist’s Statement (Jeff Kober) ................................................................................................................................... 4 Cast Bios ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Greenwood (Frank) ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Leslie Hope (Melanie) ............................................................................................................................................ -

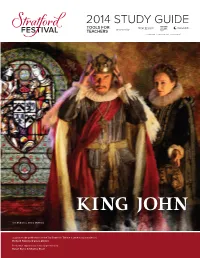

STUDY GUIDE TOOLS for TEACHERS Sponsored By

2014 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by Tom McCamus, Seana McKenna Support for the 2014 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre is generously provided by Richard Rooney & Laura Dinner Production support is generously provided by Karon Bales & Charles Beall Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 6 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 7 Sources and Origins .................................................................................................... 8 Stratford Festival Production History ......................................................................... 9 The Production Artistic Team and Cast ............................................................................................... 10 Lesson Plans and Activities Creating Atmosphere .......................................................................................... 11 Mad World, Mad Kings, Mad Composition! ........................................................ 14 Discussion Topics .............................................................................................. -

View That Includes Their Perceptions of Time, in Which Their Own Future Is Naturally Hidden from Them

Reading In and Out of Order: Living In and Around an Extended Fiction DOI https://doi.org/10.32393/jlmms/2020.0001 Published on Fri, 01/24/2020 - 00:00 Many series books recount the life of a character growing up over a sequence of titles, offering a strong sense of clear progression. Readers, however, may encounter this series out of order, or they may encounter numerous adapted versions of a story. Either way, they have to decide their own interpretative priorities. Back to top Introduction The concept of a sequence implies an orderly progression. A series of books conveys the sense of a logical advancement through a character’s life or a succession of events, intelligibly assembled into a system that is sometimes even numbered for maximum clarity. Such a sequence of novels frequently uses time as an organizer—either moving through part of a character’s lifespan or manipulating the calendar to run on a repeat cycle through (for example) Nancy Drew’s eighteenth summer. We know that life is not as tidy as the stories conveyed in books. But, in the case of series, even the material presentation of the books is misleading; despite the neat row of ascending numbers on the books’ spines, readers encounter a series of titles in partial, messy, sometimes consuming, and sometimes unsatisfying ways. Furthermore, in the clutter and circularity of contemporary culture, book series in their pristine order on the shelf frequently do not represent the only versions of characters and events. Media adaptations, publishers’ reworkings, fan variations, and a plethora of consumables all offer forms of what we might call “re- presentation,” and there is no telling what route through this busy landscape of reiteration any particular reader may take, or what version of the story they may encounter before reaching the original version. -

Gleeks Rejoice! Alex Newell to Perform with Boston Gay Men's

Gleeks Rejoice! Alex Newell to Perform with Boston Gay Men’s Chorus Courtesy of Boston Gay Men’s Chorus Just in time for Pride, Boston Gay Men’s Chorus will perform “Can’t Stop the Beat,” the biggest production in its 32-year history, on June 12, 13, and 15 at New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall. The concerts feature Alex Newell who stars as the show-stopping transgender teen Wade “Unique” Adams on FOX’s hit series Glee. Newell will also share the stage with the Chorus June 7 in his hometown of Lynn for a special Outreach Concert at Lynn Auditorium, part of the Chorus’s mission of community engagement. Proceeds from the concert will be donated to 13 LGBT-related and North Shore nonprofits (AIDS Action Committee, Children's Law Center of MA, Boys and Girls Club of Lynn, Cerebral Palsy of Eastern MA, Family & Children's Services, Girls, Inc., YMCA of Metro North, Gregg Neighborhood House, Straight Ahead Ministries, Mass. Coalition for the Homeless, RAW Artworks, Catholic Charities North, and Camp Fire of the North Shore). In this Q&A, Boston Gay Men’s Chorus Music Director Reuben M. Reynolds III takes us through the show! Q: Collaborating with Alex Newell sounds pretty exciting. What can audiences expect? A: Alex has such an amazing story. He’s from Lynn and he competed on a TV show called The Glee Project. As one of the winners he was cast in an episode of Glee. Well, everyone loved him so much he’s now a regular cast member. -

Uvisno "Acting Is Handed on from Actor to Actor

Inaide the Stratford Festival uviSNO "Acting is handed on from actor to actor. It's the only way to do it... from observing the people who came before you. That is really the way theatre goes" In OFFSTAGE ONSTAGE: Inside the Stratford Festival, Stratford cameras go backstage during an entire season to capture the creative spirit at the heart of a treasured Canadian theatre company. For five decades, the Festival's stage has been home to the world's great plays and performers. Award-winning director John N. Smith (The Boys of St. Vincent), given unprecedented access backstage, offers a fascinating look at the personalities and the production process behind live theatre performance. Peek into William Hutt's dressing room as he does his vocal warm-ups before Twelfth Night. Watch Martha Henry command the stage in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? Observe an up-and-coming generation of young performers who learn from the masters. Meet dozens of artists, craftspeople and technicians who reveal their secrets, from shoemaking, sword fighting and sound effects to makeup and mechanical monkeys. Join us behind the scenes of Canada's premier classical theatre institution ... and discover the love for the stage that drives this artistic company. Resource guide on reverse side, DIRECTOR: John N. Smith PRODUCER: Gerry Flahive 83 minutes Order number: C9102 042 Closed captioned. A decoder is required. TO ORDER NFB VIDEOS, CALL TODAY! -800-267-7710 (Canada) 1-800-542-2164 (USA) © 2002 National Film Board of Canada. A licence is required for any reproduction, television broadcast, sale, rental or public screening. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAY CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 16 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2020 $NOT HS 23 BILLY STRINGS BG 1 CONRO DA 24 FLEETWOOD MAC B200 60, 182; INT 14; SIERRA HULL BG 6 ADAM LAMBERT RO 46 THE 1975 MO 17; RKA 25; RO 16, 38 BLACKBEAR A40 37; H100 43; HA 26; RO 48 BRADLEY COOPER B200 167; STX 6 PCA 5 SAM HUNT B200 28; CA 5, 35; CS 9, 10; H100 MIRANDA LAMBERT CA 31; CS 12, 15; H100 220 KID DA 10; DES 48 BLACKPINK WM 10 BOB CORRITORE BL 14 FLIPP -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld.