The Festive Remembrance of Shakespeare: a Comparative Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Dean Maureen Lally-Green

THE FALL/WINTER 2016 The Duquesne University School of Law Magazine for Alumni and Friends The Spirit of Community: Interim Dean Maureen Lally-Green ALSO INSIDE: Article #1 Article #1 Article #1 MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN THE DuquesneLawyer is published semi-annually by Duquesne University Interim Dean’s Message Office of Public Affairs CONTACT US www.duq.edu/law [email protected] 412.396.5215 © 2016 by the Duquesne University School of Law Reproduction in whole or in part, without permission Text to come.... of the publisher, is prohibited. INTERIM DEAN Nancy Perkins Maureen Lally-Green EDITOR-IN-CHIEF AND DIRECTOR OF Interim Dean LAW ALUMNI RELATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT Jeanine L. DeBor DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Colleen Derda CONTRIBUTORS Joshua Allenberg Cassandra Bodkin Maria Comas Samantha Coyne Jeanine DeBor Colleen Derda Possible pull out text here... Pete Giglione Jamie Inferrera Nina Martinelli Carlie Masterson CONTENTS Mary Olson TO AlisonCOME Palmeri Nicholle Pitt FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Rose Ravasio Phil Rice Interim Dean Nancy Perkins: News from The Bluff 2 TO COME Samantha Tamburro The Art of the Law 8 Rebecca Traylor Clinics 6 Hillary Weaver The Inspiring Journey of Sarah Weikart Faculty Achievements 18 Tynishia Williams Justice Christine Donohue 10 Zachary Zabawa In Memoriam 21 Jason Luckasevic, L’00: DESIGN Bringing Justice to the Gridiron 14 Class Actions 22 Miller Creative Group Juris: Summer 2016 Student Briefs 27 Issue Preview 16 TO COMECareer Services 32 STAY INFORMED NEWS FROM THE BLUFF Duquesne achieves 2nd highest Duquesne School of Law welcomes result on Pennsylvania bar exam Professor Seth Oranburg Duquesne University School of Law graduates achieved a performance,” said Lally-Green. -

Partyman by Title

Partyman by Title #1 Crush (SCK) (Musical) Sound Of Music - Garbage - (Musical) Sound Of Music (SF) (I Called Her) Tennessee (PH) (Parody) Unknown (Doo Wop) - Tim Dugger - That Thing (UKN) 007 (Shanty Town) (MRE) Alan Jackson (Who Says) You - Can't Have It All (CB) Desmond Decker & The Aces - Blue Oyster Cult (Don't Fear) The - '03 Bonnie & Clyde (MM) Reaper (DK) Jay-Z & Beyonce - Bon Jovi (You Want To) Make A - '03 Bonnie And Clyde (THM) Memory (THM) Jay-Z Ft. Beyonce Knowles - Bryan Adams (Everything I Do) I - 1 2 3 (TZ) Do It For You (SCK) (Spanish) El Simbolo - Carpenters (They Long To Be) - 1 Thing (THM) Close To You (DK) Amerie - Celine Dion (If There Was) Any - Other Way (SCK) 1, 2 Step (SCK) Cher (This Is) A Song For The - Ciara & Missy Elliott - Lonely (THM) 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) (CB) Clarence 'Frogman' Henry (I - Plain White T's - Don't Know Why) But I Do (MM) 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New (SF) Cutting Crew (I Just) Died In - Coolio - Your Arms (SCK) 1,000 Faces (CB) Dierks Bentley -I Hold On (Ask) - Randy Montana - Dolly Parton- Together You And I - (CB) 1+1 (CB) Elvis Presley (Now & Then) - Beyonce' - There's A Fool Such As I (SF) 10 Days Late (SCK) Elvis Presley (You're So Square) - Third Eye Blind - Baby I Don't Care (SCK) 100 Kilos De Barro (TZ) Gloriana (Kissed You) Good - (Spanish) Enrique Guzman - Night (PH) 100 Years (THM) Human League (Keep Feeling) - Five For Fighting - Fascination (SCK) 100% Pure Love (NT) Johnny Cash (Ghost) Riders In - The Sky (SCK) Crystal Waters - K.D. -

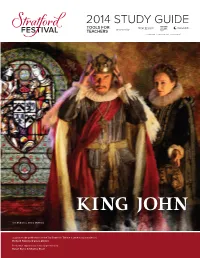

STUDY GUIDE TOOLS for TEACHERS Sponsored By

2014 STUDY GUIDE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by Tom McCamus, Seana McKenna Support for the 2014 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre is generously provided by Richard Rooney & Laura Dinner Production support is generously provided by Karon Bales & Charles Beall Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 6 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 7 Sources and Origins .................................................................................................... 8 Stratford Festival Production History ......................................................................... 9 The Production Artistic Team and Cast ............................................................................................... 10 Lesson Plans and Activities Creating Atmosphere .......................................................................................... 11 Mad World, Mad Kings, Mad Composition! ........................................................ 14 Discussion Topics .............................................................................................. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Indigo in Motion …A Decidedly Unique Fusion of Jazz and Ballet

A Teacher's Handbook for Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Production of Indigo in Motion …a decidedly unique fusion of jazz and ballet Choreography Kevin O'Day Lynne Taylor-Corbett Dwight Rhoden Music Ray Brown Stanley Turrentine Lena Horne Billy Strayhorn Sponsored by Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre's Arts Education programs are supported by major grants from the following: Allegheny Regional Asset District Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation Pennsylvania Council on the Arts The Hearst Foundation Sponsoring the William Randolph Hearst Endowed Fund for Arts Education Additional support is provided by: Alcoa Foundation, Allegheny County, Bayer Foundation, H. M. Bitner Charitable Trust, Columbia Gas of Pennsylvania, Dominion, Duquesne Light Company, Frick Fund of the Buhl Foundation, Grable Foundation, Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, The Mary Hillman Jennings Foundation, Milton G. Hulme Charitable Foundation, The Roy A. Hunt Foundation, Earl Knudsen Charitable Foundation, Lazarus Fund of the Federated Foundation, Matthews Educational and Charitable Foundation,, McFeely-Rogers Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, William V. and Catherine A. McKinney Charitable Foundation, Howard and Nell E. Miller Foundation, The Charles M. Morris Charitable Trust, Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development, The Rockwell Foundation, James M. and Lucy K. Schoonmaker Foundation, Target Corporation, Robert and Mary Weisbrod Foundation, and the Hilda M. Willis Foundation. INTRODUCTION Dear Educator, In the social atmosphere of our country, in this generation, a professional ballet company with dedicated and highly trained artists cannot afford to be just a vehicle for public entertainment. We have a mission, a commission, and an obligation to be the standard bearer for this beautiful classical art so that generations to come can view, enjoy, and appreciate the significance that culture has in our lives. -

The Power of Partnership

TALK TALK Winchester Nonprofit Org. Thurston U.S. Postage School PAID Pittsburgh, PA 555 Morewood Avenue Permit No. 145 Pittsburgh, PA 15213 www.winchesterthurston.org ThistleThistle The Power of Partnership in this issue: City as Our Campus Partnership with Pitt Asian Studies Center Young Alum Leadership Council Builds a Bridge to Beijing and Beyond Reunion 2009 Urban Arts Revealed Connects WT Students Reflections on the G-20 to Pittsburgh’s Vibrant Arts Community Painting by Olivia Bargeron, WT Class of 2018, City Campus fourth-grader. Winchester Thurston School Winter 2010 Malone Scholars Thistle TALK MAGAZINE Volume 37 • Number 1 • Winter 2010 Thistletalk is published two times per year by Winchester Thurston School for alumnae/i, parents, students, and friends of the school. Letters and suggestions are welcome. Contact Maura Farrell, Winchester Thurston School, 555 Morewood Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213. In Memoriam Editor The following members of the WT community will be missed by Maura Farrell their classmates, friends, students, and colleagues. We offer sincere Assistant Head for Planning condolences to their families. [email protected] Sara Mitchell ‘76, October 24, 2009 Alumnae/i Editor Gaylen Westfall Sara Ann Kalla ‘73, May 31, 2009 Director of Development and Alumnae/i Relations Aline Massey ’62, August 25, 2009 [email protected] Anne Sauers Brassert ‘57, August 28, 2008 Contributors David Aschkenas Suzanne Scott Kennedy ‘52, June 21, 2009 Kathleen Bishop Dionne Brelsford Antoinette Vilsack Seifert ‘32, October 6, 2009 Jason Cohn Lisa Kay Davis ‘97 Max Findley ‘11 John Holmes Condolences Ashley Lemmon ‘01 Karen Meyers ‘72 To Mrs. Marilyn Alexander on the death of her husband, To Gray Pipitone ‘14, Gianna Pipitone ‘16, Gunnar Lee Moses A’98 Robert D. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

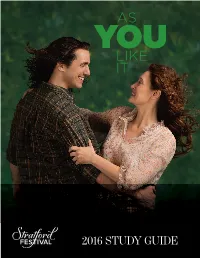

2016 Study Guide 2016 Study Guide

2016 STUDY GUIDE 2016 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER AS YOU LIKE IT BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR JILLIAN KEILEY TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by M. Fainer and by The Harkins/Manning Families In Memory of James & Susan Harkins INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 Support for the 2016 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Claire & Daniel Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Bernstein Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2016 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Cyrus Lane, Petrina Bromley. Photography by Don Dixon. Table of Contents The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Cast of Characters ...................................................................................................... 7 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................. -

A Case Study of Pittsburgh Magazine

A CASE STUDY OF PITTSBURGH MAGAZINE: An analysis of the use of Facebook and Twitter from the perspective of magazine editors and readers _____________________________________________ A Thesis presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _____________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________ by ALEXANDRIA ANNA ANTONACCI University of Missouri John Fennell, Thesis Committee Chair MAY 2014 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A CASE STUDY OF PITTSBURGH MAGAZINE: An analysis of the use of Facebook and Twitter from the perspective of magazine editors and readers presented by Alexandria Anna Antonacci, a candidate for the degree of master of arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ____________________________________ Associate Professor John Fennell ____________________________________ Assistant Professor Amanda Hinnant ____________________________________ Associate Dean Lynda Kraxberger ____________________________________ Professor Sanda Erdelez ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the Pittsburgh Magazine staff for letting me spend a semester with their company. They were welcoming and answered all my persistent questions. I would also like to thank the Duffy Fund committee, at the Missouri School of Journalism, who helped fund my research. I’m honored to have worked with an excellent team of -

The Progressive Pittsburgh 250 Report

Three Rivers Community Foundation Special Pittsburgh 250 Edition - A T I SSUE Winter Change, not 2008/2009 Social, Racial, and Economic Justice in Southwestern Pennsylvania charity ™ TRCF Mission WELCOME TO Three Rivers Community Foundation promotes Change, PROGRESSIVE PITTSBURGH 250! not charity, by funding and encouraging activism among community-based organiza- By Anne E. Lynch, Manager, Administrative Operations, TRCF tions in underserved areas of Southwestern Pennsylvania. “You must be the change you We support groups challeng- wish to see in the world.” ing attitudes, policies, or insti- -- Mohandas Gandhi tutions as they work to pro- mote social, economic, and At Three Rivers Community racial justice. Foundation, we see the world changing every day through TRCF Board Members the work of our grantees. The individuals who make up our Leslie Bachurski grantees have dedicated their Kathleen Blee lives to progressive social Lisa Bruderly change. But social change in Richard Citrin the Pittsburgh region certainly Brian D. Cobaugh, President didn’t start with TRCF’s Claudia Davidson The beautiful city of Pittsburgh (courtesy of Anne E. Lynch) Marcie Eberhart, Vice President founding in 1989. Gerald Ferguson disasters, and nooses show- justice, gay rights, environ- In commemoration of Pitts- Chaz Kellem ing up in workplaces as re- mental justice, or animal Jeff Parker burgh’s 250th birthday, I was cently as 2007. It is vital to rights – and we must work Laurel Person Mecca charged by TRCF to research recall those dark times, how- together to bring about lasting Joyce Redmerski, Treasurer the history of Pittsburgh. Not ever, lest we repeat them. change. By doing this, I am Tara Simmons the history that everyone else Craig Stevens sure that we will someday see would be recalling during this John Wilds, Secretary I’ve often heard people say true equality for all. -

Kagame's Visit Sparks Protest, Controversy Kagame, Cohon

Manage the job fair, CMU needs to initiate Miller Gallery opens its improve your résumé, learn community discussion presentation of city-wide about the new fall EOC about Rwanda program • A10 Pittsburgh Biennial • C8 CAREER WEEK FORUM PILLBOX thetartan.org @thetartan September 19, 2011 Volume 106, Issue 4 Carnegie Mellon’s student newspaper since 1906 Kagame, Cohon announce Rwandan program Kagame’s visit sparks SUJAYA BALACHANDRAN Rwanda. of the Carnegie Institute of Prior to the ceremony and Junior Staffwriter Kagame delivered his Technology. announcement in Rangos, protest, controversy keynote address to a packed Kagame’s visit was not met The Tartan interviewed Co- MADELYN GLYMOUR Although embroiled in crowd of attendees who un- without opposition, however. hon to obtain background lack of free speech in Rwan- Assistant News Editor controversy, Rwandan Presi- derwent security checks that A group of protesters clus- knowledge of the partnership da. dent Paul Kagame’s visit to included metal detectors and tered near the bus stop on between Carnegie Mellon and Last year, Reporters With- Carnegie Mellon last Friday pat-downs by security offi - Forbes Avenue, with shouts the new program in Kigali. Protesters gathered out- out Borders ranked Rwanda was a signifi cant event, as cials. The event, which was of “Kagame! Genocidaire!” al- Cohon noted that Rwan- side the University Center to 169th out of 178 countries in both he and University Presi- held in the University Center’s leging Kagame’s involvement da’s government, recognizing speak out against Carnegie its worldwide freedom of the dent Jared Cohon announced Rangos Hall, was hosted by in the murders of Congolese Carnegie Mellon’s strengths in Mellon’s partnership with press index. -

City Theatre Advances New Play Development in the Midst of the Covid-19 Pandemic

CONTACT: Nikki Battestilli Marketing Director 412-431-4400 x230 [email protected] CityTheatreCompany.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CITY THEATRE ADVANCES NEW PLAY DEVELOPMENT IN THE MIDST OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC Pittsburgh, PA (October 25, 2020): City Theatre remains committed to its support of new play development and launched several new works initiatives this fall, finding innovative ways to support playwrights. City Theatre is excited to announce the creation of the Kemp Powers Commission Fund for Black Playwrights. The fund is made possible through the generous support of award-winning playwright Kemp Powers (author of last season's One Night in Miami..., which has just been adapted by Mr. Powers as a film distributed by Amazon Studios) and will offer an annual commission and developmental support to an early- career Black playwright. "Back in 2019, City Theatre welcomed me with open arms by producing one of my plays, hosting a staged reading of another play, and inviting me to Pittsburgh so that I could interact with some of the dynamic youth playwrights of the city,” said Mr. Powers. “As an artist, it is rare to receive that kind of institutional and community support, and it inspired me to want to pay it forward by offering support of my own to the next generation of storytellers." The first artist to receive the commission is playwright Ty Greenwood. Mr. Greenwood is a Pittsburgh native, Washington & Jefferson College alumni, and recent graduate of the Carnegie Mellon School of Drama's MFA in Dramatic Writing program. The commission will give him the flexibility to work on a new play of his choosing and includes built in developmental support as part of the process.