“The World in a Small Rectangle”: Spatialities in Monika Fagerholm's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American-Scandinavian Foundation

THE AMERICAN-SCANDINAVIAN FOUNDATION BI-ANNUAL REPORT JULY 1, 2011 TO JUNE 30, 2013 The American-Scandinavian Foundation BI-ANNUAL REPORT July 1, 2011 to June 30, 2013 The American-Scandinavian Foundation (ASF) serves as a vital educational and cultural link between the United States and the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. A publicly supported nonprofit organization, the Foundation fosters cultural understanding, provides a forum for the exchange of ideas, and sustains an extensive program of fellowships, grants, internships/training, publishing, and cultural events. Over 30,000 Scandinavians and Americans have participated in its exchange programs over the last century. In October 2000, the ASF inaugurated Scandinavia House: The Nordic Center in America, its headquarters, where it presents a broad range of public programs furthering its mission to reinforce the strong relationships between the United States and the Nordic nations, honoring their shared values and appreciating their differences. 58 PARK AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10016 • AMscan.ORG H.M. Queen Margrethe II H.E. Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson Patrons of Denmark President of Iceland 2011 – 2013 H.E. Tarja Halonen H.M. King Harald V President of Finland of Norway until February, 2012 H.M. King Carl XVI Gustaf H.E Sauli Niinistö of Sweden President of Finland from March, 2012 H.R.H. Princess Benedikte H.H. Princess Märtha Louise Honorary of Denmark of Norway Trustees H.E. Martti Ahtisaari H.R.H. Crown Princess Victoria 2011 – 2013 President of Finland,1994-2000 of Sweden H.E. Vigdís Finnbogadóttir President of Iceland, 1980-1996 Officers 2011 – 2012 Richard E. -

Eva E. Johansson – Realismens Röster

Realismens röster Kvinnliga kontorister i mellankrigstidens finlandssvenska litteratur Vad hände med det realistiska berättandet i den moderna finlandssvenska litteraturen efter modernismens genombrott? Det är en av de frågor som ställs i avhandlingen Realismens röster, där Eva E. Johansson utforskar kontorsskildringen som Eva E. Johansson litterär genre. Avhandlingen lyfter fram en grupp finlandssvenska författare under mellankrigstiden – Anna Bondestam, May Hartman, Ingegerd Lundén, Margit Niininen, Ingrid Qvarnström, Allan Tallqvist, | 2017 E. Johansson Eva | Realismens röster Elmer Diktonius och Ralf Parland. I centrum står Realismens röster de tre kontorsromanerna Bara en kontorsflicka, En gedigen flicka och Fröken Elna Johansson, skrivna Kvinnliga kontorister i mellankrigstidens finlandssvenska litteratur under 1920- och 1930-talet. Genom kontorsskildringarna undersöker avhandlingen det realistiska berättandets särdrag – dess modus – men också dess konstnärliga etos: dess affirmativa hållning till berättandets mimesis. Avhandlingen argumenterar för att realistiskt berättande i grunden är mångstämmigt, och att dess samhällskritiska potential finns i de dissonanser som uppstår mellan berättelsen olika röster. Åbo Akademis förlag | ISBN 978-951-765-856-0 Eva E. Johansson (f. 1960) tog sin magisterexamen vid Helsingfors universitet, och är verksam som gymnasielärare i svenska och litteratur på Åland. Omslag, grafisk form och ombrytning: Margita Lindgren/Ekenäs TypoGrafi Omslagsfotografier: Pärmbilder för Ingrid Qvarnströms roman En gedigen -

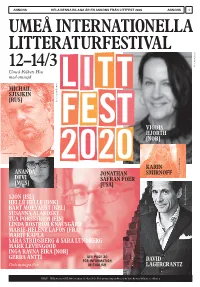

Littfest-Program2020-Web.Pdf

ANNONS HELA DENNA BILAGA ÄR EN ANNONS FRÅN LITTFEST 2020 ANNONS 1 UMEÅ INTERNATIONELLA LITTERATURFESTIVAL 12–14/3 Anette Brun Foto: Umeå Folkets Hus med omnejd MICHAIL SJISJKIN [RUS] Frolkova Jevgenija Foto: VIGDIS HJORTH [NOR] KARIN ANANDA JONATHAN SMIRNOFF Gunséus Johan Foto: Obs! Biljetterna till Littfest 2020 är slutsålda.se sidan För X programpunkter som inte kräver biljett, DEVI SAFRAN FOER [MUS] [USA] Foto: Foto: Timol Umar SJÓN [ISL] HELLE HELLE [DNK] Caroline Andersson Foto: BART MOEYAERT [BEL] SUSANNA ALAKOSKI TUA FORSSTRÖM [FIN] LINDA BOSTRÖM KNAUSGÅRD MARIE-HÉLÈNE LAFON [FRA] MARIT KAPLA SARA STRIDSBERG & SARA LUNDBERG MARK LEVENGOOD INGA RAVNA EIRA [NOR] GERDA ANTTI SEE PAGE 30 FOR INFORMATION DAVID Foto: Jeff Mermelstein Jeff Foto: Och många fler… IN ENGLISH LAGERCRANTZ IrmelieKrekin Foto: OBS! Biljetterna till Littfest 2020 är slutsålda. För programpunkter som inte kräver biljett, se sidan 4 Olästa e-böcker? Odyr surf. Har du missat vårens hetaste boksläpp? Med vårt lokala bredband kan du surfa snabbt och smidigt till ett lågt pris, medan du kommer ikapp med e-läsningen. Vi kallar det för odyr surf – och du kan lita på att våra priser alltid är låga. Just nu beställer du bredband för halva priset i tre månader. Odyrt och okrångligt = helt enkelt oslagbart! Beställ på odyrsurf.se P.S. Är du redan prenumerant på VK eller Folkbladet köper du bredband för halva priset i tre månader. Efter kampanjperioden får du tio kronor rabatt per månad på ordinarie bredbandspris, så länge du är prenumerant. ANNONS HELA DENNA BILAGA ÄR EN -

09-29 Drömmen Om Jerusalem I Samarb. Med Svenska Kyrkan Och Piratförlaget 12.00

09-29 Tid 12.00 - 12.45 Drömmen om Jerusalem Drömmen om Jerusalem realiserades av Jerusalemsfararna från Nås som ville invänta Messias ankomst på plats. Vissa kristna grupper, ibland benämnda kristna sionister, kämpar för staten Israel och för att alla judar ska återföras till Israel – men med egoistiska syften. När alla judar återvänt till det heliga landet kommer Messias tillbaka för att upprätta ett kristet tusenårsrike, tror man. Dessa grupper har starka fästen i USA och anses ha betydande inflytande i amerikansk utrikespolitik. De söker också aktivt etablera sig som maktfaktor i Europa. Kan man verkligen skilja mellan religion och politik i Israel-Palestinakonflikten? Är det de extremreligiösa grupperingarna som gjort en politisk konflikt till en religiös konflikt? Medverkande: Jan Guillou, författare och journalist, Mia Gröndahl, journalist och fotograf, Cecilia Uddén, journalist, Göran Hägglund, partiledare för Kristdemokraterna. Moderator: Göran Gunner, forskare, Svenska kyrkan. I samarb. med Svenska kyrkan och Piratförlaget 09-29 Tid 16.00 - 16.45 Små länder, stora frågor – varför medlar Norge och Sverige? Norge och Sverige har spelat en stor roll vid internationella konflikter. Tryggve Lie och Dag Hammarskjöld verkade som FN:s generalsekreterare. I dagens världspolitik är svenskar och norrmän aktiva i konfliktområden som Östra Timor, Sri Lanka, Colombia och Mellanöstern. Hur kommer det sig att så små nationer som Norge och Sverige fått fram en rad framstående personer inom freds- och konflikthantering? Medverkande: Lena Hjelm-Wallén, tidigare utrikesminister, Kjell-Åke Nordquist, lektor i freds- och konfliktforskning vid Uppsala universitet, Erik Solheim, specialrådgivare till Norska UD. Moderator: Cecilia Uddén, journalist. I samarb. med Svenska kyrkan och Norges ambassad i Stockholm 09-29 Tid 17.00 - 17.45 Vem skriver manus till mitt liv? Film och religion – livsåskådning på vita duken De avgörande föreställningarna för hur det goda livet ser ut formas i vår tid av filmer, TV-serier, varumärken, logotyper och reklambudskap. -

TORSTAI/TORSDAG 27.10. ALEKSIS KIVI – Suuret Kertojat

TORSTAI/TORSDAG 27.10. ALEKSIS KIVI – Suuret kertojat 11.00 AVAJAISET 13.30 Iiro Rantala Suomen Messujen tervehdys, toimitusjohtaja Christer Haglund NYT SEN VOI JO KErtoa Kansainvälisesti kuuluisin jazzmuusikkomme on kirjoittanut musii- Viron tervehdys, Viron tasavallan presidentti Toomas Hendrik Ilves killisen elämäkertansa. Nyt sen voi jo kertoa on ihan hauska ja täysin ainutlaatuinen elämäkertojen ja taiteilijakirjojen joukossa. Avajaispuhe, sarjakuvataiteilija Juba Tuomola Aidosti Iiron näköinen, rehellinen, moneen suuntaan aukeava ja Rakkaudesta kirjaan -tunnustuspalkinnon jako, paljon informaation täyteinen. Teos Suomen Kustannusyhdistyksen hallituksen pj Anna Baijars Virolaiset laulajat ja kitarasankarit Riho Sibul, Jaanus Nõgisto ja HELSINGIN SANOMAT Jaak Tuksam musisoivat. 14.00 ViiVI JA RIVO-Riitta aaMUKAHVILLA 12.00 Toomas Hendrik Ilves Juba Tuomola (Viivi ja Wagner) ja Pertti Jarla (Fingerpori) ker- OMALLA ÄÄNELLÄ S tovat, missä kulkee hyvän ja huonon maun välinen raja. Tekijät Viron tasavallan presidentti Toomas Hendrik Ilves on työskennellyt myös kommentoivat HS:n kisaa, jossa lehden lukijat voivat keksiä Viron suurlähettiläänä useissa maissa, kaksi kertaa Viron ulko- omat puhekuplat suosikkisarjoihin. Haastattelijoina Esa Mäkinen ministerinä sekä Euroopan parlamentin ja Viron riigikogun jäse- ja Jukka Petäjä. nenä. Omalla äänellä on Ilveksen kertomus matkasta kotimaahan ja politiikan huipulle. Presidentti valottaa kirjassa näkemyksiään 15.00 TÄHTIHETKI: Jari TERVO Viron paluusta Euroopan kartalle. Ilveksen kanssa keskustelevat -

International Evaluation of Research and Doctoral Training At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto INTERNATIONAL EVALUATION OF RESEARCH AND DOCTORAL TRAINING AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI 2005–2010 RC-Specific Evaluation of GLW – Genres of Literary Worldmaking Seppo Saari & Antti Moilanen (Eds.) Evaluation Panel: Humanities INTERNATIONAL EVALUATION OF RESEARCH AND DOCTORAL TRAINING AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI 2005–2010 RC-Specific Evaluation of GLW – Genres of Literary Worldmaking Seppo Saari & Antti Moilanen (Eds.) University of Helsinki Administrative Publications 80/88 Evaluations 2012 Publisher: University of Helsinki Editors: Seppo Saari & Antti Moilanen Title: Type of publication: International Evaluation of Research and Doctoral Training at the University of Evaluations Helsinki 2005–2010 : RC-Specific Evaluation of GLW – Genres of Literary Worldmaking Summary: Researcher Community (RC) was a new concept of the participating unit in the evaluation. Participation in the evaluation was voluntary and the RCs had to choose one of the five characteristic categories to participate. Evaluation of the Researcher Community was based on the answers to the evaluation questions. In addition a list of publications and other activities were provided by the TUHAT system. The CWTS/Leiden University conducted analyses for 80 RCs and the Helsinki University Library for 66 RCs. Panellists, 49 and two special experts in five panels evaluated all the evaluation material as a whole and discussed the feedback for RC-specific reports in the panel meetings in Helsinki. The main part of this report is consisted of the feedback which is published as such in the report. Chapters in the report: 1. -

Nodes of Contemporary Finnish Literature

Nodes of Contemporary Finnish Literature Edited by Leena Kirstinä Studia Fennica Litteraria The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Markku Haakana, professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Timo Kaartinen, professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Kimmo Rentola, professor, University of Turku, Finland Riikka Rossi, docent, University of Helsinki, Finland Hanna Snellman, professor, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Lotte Tarkka, professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen, Secretary General, Dr. Phil., Finnish Literature Society, Finland Pauliina Rihto, secretary of the board, M. A., Finnish Literary Society, Finland Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Nodes of Contemporary Finnish Literature Edited by Leena Kirstinä Finnish Literature Society • Helsinki Studia Fennica Litteraria 6 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. © 2012 Leena Kirstinä and SKS License CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International A digital edition of a printed book first published in 2012 by the Finnish Literature Society. -

Anna Möller-Sibelius MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL 2007 Anna Möller-Sibelius (F

Anna Möller-Sibelius MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL 2007 Anna Möller-Sibelius (f. 1971) är forskare och kritiker Pärm, foto: Anna Möller-Sibelius Åbo Akademis förlag Biskopsgatan 13, FIN-20500 ÅBO, Finland Tel. int. +358-2-215 3292 Fax int. + 358-2-215 4490 E-post: [email protected] http://www.abo.fi/stiftelsen/forlag/ Distribution: Oy Tibo-Trading Ab PB 33, FIN-21601 PARGAS, Finland Tel. int. +358-2-454 9200 Fax. int. +358-2-454 9220 E-post: [email protected] http://www.tibo.net MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL MÄNSKOBLIVANDETS LÄGGSPEL En tematisk analys av kvinnan och tiden i Solveig von Schoultz poesi Anna Möller-Sibelius ÅBO 2007 ÅBO AKADEMIS FÖRLAG – ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY PRESS CIP Cataloguing in Publication Möller-Sibelius, Anna Mänskoblivandets läggspel : en tematisk analys av kvinnan och tiden i Solveig von Schoultz poesi / Anna Möller-Sibelius. - Åbo : Åbo Akademis förlag, 2007. Diss.: Åbo Akademi. – Summary. ISBN 978-951-765-372-5 ISBN 978-951-765-372-5 ISBN 978-951-765-372-2 (digital) Åbo Akademis tryckeri Åbo 2007 Och hur kan det ta så lång tid att börja förstå sig själv och andra, hur kan det dröja så länge innan man blir mänska? Varje dikt är en bit i mänskoblivandets läggspel som väl aldrig blir färdigt. (Den heliga oron) Lika litet som livet kommer med definitiva lösningar, lika litet kan författaren göra det när han lägger pussel med bitar ur det vi kallar verklighet. Men man vet vad man hoppas på. (Ur författarens verkstad) Nu när jag ser tillbaka tycker jag att det under alltsammans går en envis strävan att komma vidare, jag menar: att genom att helt och fullt bejaka det här, att vara kvinna, kunna nå fram till en fri rymd där båda könen förenas i det viktigaste: att vara mänska. -

A Selection of Finnish Titles (Fiction and Non-Fiction) (Pdf)

1 AUTUMN 2019 A Selection of Finnish Titles (Fiction and Non-Fiction) 2 3 FILI – Finnish Literature Exchange promotes the publication of Finnish literature in translation around the world. FILI • distributes approx. €600,000 in translation and printing, promotional and readers' report grants for over 400 different projects annually • organises Editors’ Week events for publishers to visit Finland from abroad • participates in publishing trade fairs abroad • acts as a focal point for translators of Finnish literature • maintains a database of translations of Finnish literature published in other languages and collects data on translation rights sold abroad. We deal with fiction, children’s and young adult books, non-fiction, poetry, comics and graphic novels written in Finnish, Finland-Swedish and Sámi. FILI serves as a support organisation for the export of literature, while publishers and literary agencies handle the sale of translation rights. FILI, founded in 1977, is a department of the Finnish Literature Society, and around 80% of our funding comes from public sources. 4 5 AUTUMN 2019 A Selection of Finnish Titles FICTION . 6 GRAPHIC NOVEL . 25 NON-FICTION . 27 REMEMBER THESE . 35 Fiction 6 Fiction 7 Monika Fagerholm: Elina Hirvonen: Who Killed Bambi? Red Storm Who Killed Bambi? is a literary novel about A heartbreaking story of an Iraqi family’s female friendship and rivalry, boys at the long journey to Finland – and of their mercy of each other, and families breaking dream of peace. apart. About careless living, and the death A small boy grows up in Iraq under Saddam Hussein, of innocence. where fear is always present. -

Introduction to Scandinavian Culture and Society (7,5

Introduction to Scandinavian Culture and Society (7,5 hp) SASH55 Introduction to Scandinavian Culture and Society Department of Arts and Cultural Sciences Intermedia studies Accepted by the syllabus committee 2021.06.01 Electronic texts are available through LUBSearch. Additional texts available via Canvas (teaching platform). Additional short texts may apply. Course Literature Agger, Gunhild 2015: Strategies in Danish Film Culture – and the Case of Susanne Bier. Kosmorama #259 (www.kosmorama.dk). Available at: http://www.kosmorama.org/ServiceMenu/05-English/Articles/Susanne-Bier.aspx Andersen, H.C., pick and read three fairy tales at: http://www.andersen.sdu.dk/vaerk/hersholt/index_e.html Arrhenius, Thordis 2010: The vernacular on display. Skansen open-air museum in 1930s Stockholm. In Mattsson, Helena & Wallenstein, Sven-Olov (eds.): Swedish Modernism. Archtecture, consumption and the welfare state. London: Black Dog Publishing. ISBN 1906155984, (16p.). Bjørnson, Øyvind 2001: The Social Democrats and the Norwegian Welfare State: Some Perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of History vol. 26, no. 3, p 197-223, ISSN 0346- 8755, (26p). Brodén, Daniel 2017: Old-school modernism? On the cinema of Roy Andersson. In Journal of Scandinavian Cinema, vol. 7, no. 1, ISSN 2042-7891, (6p). Available through LUBSearch). Burnett, Robert 1992: Dressed for Success: Sweden from Abba to Roxette. Popular Music, Vol. 11, No. 2, p 141-150, ISSN: 0261-1430, (10p). Christiansen, Niels Finn & Petersen, Klaus 2001: The Dynamics of Social Solidarity: The Danish Welfare State, 1900-2000. Scandinavian Journal of History vol. 26, no. 3, p 177-196, ISSN 0346-8755, (19p). Fridegård, Jan 1944: The Mill Ration. Will be available on Canvas. -

Joutsen Svanen 2016 Joutsen Svanen 2016

JOUTSEN SVANEN 2016 JOUTSEN SVANEN 2016 Kotimaisen kirjallisuudentutkimuksen vuosikirja Årsbok för forskning i finländsk litteratur Yearbook of Finnish Literary Research Toimittaja/Redaktör/Editor: Harri Veivo JOUTSEN / SVANEN 2016 Kotimaisen kirjallisuudentutkimuksen vuosikirja Årsbok för forskning i finländsk litteratur Yearbook of Finnish Literary Research http://blogs.helsinki.fi/kirjallisuuspankki/joutsensvanen-2016/ Julkaisija: Suomalainen klassikkokirjasto, Helsingin yliopiston Suomen kielen, suomalais-ugrilaisten ja pohjoismaisten kielten ja kirjallisuuksien laitos. PL 3, 00014 Helsingin yliopisto Utgivare: Finländska klassikerbiblioteket, Finska, finskugriska och nordiska institutionen vid Helsingfors universitet. PB 3, 00014 Helsingfors universitet Publisher: Finnish Classics Library, Department of Finnish, Finno-Ugrian and Scandinavian Studies. P.O. Box 3, 00014 University of Helsinki Päätoimittaja / Chefredaktör / Editor: Jyrki Nummi (jyrki.nummi[at]helsinki.fi) Vastaava toimittaja (2016) / Ansvarig redaktör (2016) / Editor-in-Chief (2016): Harri Veivo (harri.veivo[at]unicaen.fr) Toimituskunta / Redaktionsråd / Board of Editors: Jyrki Nummi (pj./ordf./Chair), Kristina Malmio, Saija Isomaa, Anna Biström, Eeva-Liisa Bastman ISSN 2342–2459 URN:NBN:fi-fe201703225378 Pysyvä osoite / Permanent adress / Permanent address: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe201703225378 Taitto: Jari Käkelä SISÄLLYS INNEHÅLL Jyrki Nummi: Foreword ........................................................................................................7 Harri -

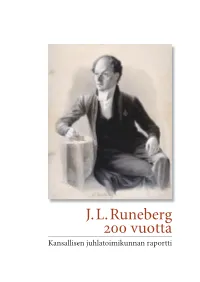

Raportti.Pdf

J. L. Runeberg 200 vuotta Kansallisen juhlatoimikunnan raportti Sisältö Kuvamme Runebergista on tullut eläväksi 3 Sanoin & kuvin & sävelin – Kansallinen juhlatoimikunta 4 Summa summarum – eli voiko saldosta puhua? 5 Humanismin perintö 9 J. L. Runeberg 200 sanoin & kuvin & sävelin 15 Julkaisujen juhlavuosi 25 Juhlavuoden tuotteita 28 Runebergin juhlintaa kautta maan 30 Runebergin jäljillä – Juhlatoimikunnan jäsenten osaraportteja 31 Runebergin jäljillä 32 Firandet av J. L. Runebergs 200-års jubileumsår i Jakobstad 33 Kommentarer över firandet av Runebergs jubileumsår i Pargas 36 J. L. Runebergin juhlavuosi Porvoossa 38 Runebergin juhlavuosi Ruovedellä 42 Pölyjä rintakuvista ja muistomerkeistä, Saarijärvi 46 Tapahtumia Saarijärvellä 2004 50 Turussa juhlittiin Runebergia sanoin, sävelin ja räpätenkin 54 Koululainen Runeberg Vaasassa 56 ”Runeberg 200 vuotta” -juhlavuoden tapahtumia Vaasassa 57 Ruotusotamies Bång ja Sven Dufva, SKS 59 Svenska litteratursällskapets Runebergsprojekt 2004 62 Litteet 68 1. Organisaatio/Organisation 69 2. Avustukset Runeberg-tapahtumille 71 3. Laulu liitää yli meren maan – J. L. Runeberg 200 vuotta Sången flyger över land och hav – J. L. Runeberg 200 år 75 4. Kirjoja ja julkaisuja / Böcker och publikationer 78 Julkaisija: Kansallinen J. L. Runebergin 200-vuotisjuhlatoimikunta Toimittaja: Sari Hilska Ulkoasu: Peter Sandberg Kannen kuva: J. L. Runeberg, Johan Knutson, 1848 www.runeberg.net 2 Per-Håkan Slotte Kuvamme Runebergista on tullut eläväksi Kansallinen J. L. Runebergin 200-vuotistoimikunta on saattanut työnsä pää- tökseen. Toivomukseni on, että tämä raportti antaa yleiskuvan sekä toimikunnan työstä että juhlavuoden ohjelmasta. Toimikunta vastasi juhlavuoden valtakunnalli- sesta markkinoinnista ja tapahtumien tukemisesta. Lisäksi se järjesti valtakunnallisen pääjuhlan Porvoossa helmikuun 5. päivänä 2004. Kuva kansallisrunoilijastamme on juhlavuoden myötä muuttunut monisäikei- semmäksi. ”Ajattelin Runebergin ennen vanhukseksi, joka keksi Runebergin tortun.