The Legacy of Futurism's Obsession with Speed in 1960S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6. Poesia Del Futurismo: Marinetti, Folgore E Soffici Il Paroliberismo E Le Tavole Parolibere Futuriste

6. Poesia del futurismo: Marinetti, Folgore e Soffici Il paroliberismo e le tavole parolibere futuriste PAROLIBERISMO = parole in libertà → è uno stile letterario introdotto dal Futurismo in cui: le parole che compongono il testo non hanno alcun legame grammaticale-sintattico fra loro le parole non sono organizzate in frasi e periodi viene abolita la punteggiatura i principi e le regole di questa tecnica letteraria furono individuati e scritti da Marinetti nel "Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista" dell' 11 maggio 1912 TAVOLE PAROLIBERE: La tavola parolibera è un tipo di poesia che visualizza il messaggio o il contrario del messaggio anche con la disposizione particolare grafico-tipografica di lettere, parole, brani di testi, versi o strofe. (tradizione lontana di Apollinere) FILIPPO TOMMASO MARINETTI (1876-1944) Fu un poeta, scrittore e drammaturgo italiano. È conosciuto soprattutto come il fondatore del movimento futurista, la prima avanguardia storica italiana del Novecento. Nacque in Egitto, trascorse i primi anni di vita ad Alessandria d'Egitto. L'amore per la letteratura emergeva dagli anni del collegio: a 17 anni fondò la sua prima rivista scolastica, Papyrus La morte di suo fratello minore era il primo vero trauma della vita di Marinetti, che dopo aver conseguito la laurea a Genova, decise di abbandonare la giurisprudenza e scelse la letteraratura. Dopo alcuni anni aveva un altro grave lutto familiare: morì la madre, che da sempre lo incoraggiava a praticare l'arte della poesia. Le sue prime poesie in lingua francese, pubblicate su riviste poetiche milanesi e parigine, influenzavano queste poesie Mallarmé e Gabriele D’Annunzio e componeva soprattutto versi liberi di tipo simbolista Tra il 1905 e il 1909 diresse la rivista milanese Poesia. -

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity Matilde Marcolli 2015 • Mythopoesis: the capacity of the human mind to spontaneously generate symbols, myths, metaphors, ::: • Psychology (especially C.G. Jung) showed that the human mind (especially the uncon- scious) continuously generates a complex lan- guage of symbols and mythology (archetypes) • Religion: any form of belief that involves the supernatural • Mythopoesis does not require Religion: it can be symbolic, metaphoric, lyrical, visionary, without any reference to anything supernatural • Visionary Modernity has its roots in the Anarcho-Socialist mythology of Progress (late 19th early 20th century) and is the best known example of non-religious mythopoesis 1 Part 1: Futurist Trains 2 Trains as powerful symbol of Modernity: • the world suddenly becomes connected at a global scale, like never before • trains collectively drive humankind into the new modern epoch • connected to another powerful symbol: electricity • importance of the train symbolism in the anarcho-socialist philosophy of late 19th and early 20th century (Italian and Russian Futurism avant garde) 3 Rozanova, Composition with Train, 1910 4 Russolo, Dynamism of a Train, 1912 5 From a popular Italian song: Francesco Guccini \La Locomotiva" ... sembrava il treno anch'esso un mito di progesso lanciato sopra i continenti; e la locomotiva sembrava fosse un mostro strano che l'uomo dominava con il pensiero e con la mano: ruggendo si lasciava indietro distanze che sembravano infinite; sembrava avesse dentro un potere tremendo, la stessa forza della dinamite... ...the train itself looked like a myth of progress, launched over the continents; and the locomo- tive looked like a strange monster, that man could tame with thought and with the hand: roaring it would leave behind seemingly enor- mous distances; it seemed to contain an enor- mous might, the power of dynamite itself.. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

DINO RISI - a Film Series Highlights of Spring 2017’S DINO RISI - a Film Series

Become a Sponsor of the Homage to Lina Wertmüller September 23, 2017 • San Francisco’s Castro Theatre Aday-longcinematiccelebrationofLinaWertmüller,thegroundbreaking,pioneeringwomandirector andvisionarywhosefearless,polemicalandprovocativefilmshaveleftindeliblemarksandinfluence ontheinternationalentertainmentfield. Theserieswillshowcasetheregionalpremieresofnew2K restorationsofLinaWertmüller’smostcelebratedworks:thefilmofoperaticemotionandsubver - sivecomedy, Love and Anarchy ;thecontroversialfilmaboutsex,loveandpolitics – Swept Away ; Seven Beauties – theNeapolitantalenominatedforfourAcademyAwards®,including BestDirector( first time ever for a woman director );theraucoussexcomedy The Seduction of Mimi .Aspecialpresentationofthedocumentaryfilmprofile Behind the White Glasses willbe highlightedwiththefilm’sdirectorValerioRuizinperson. G N Thisspecialseriesissupportedbythe TheItalianCulturalInstituteofSanFrancisco,theConsulate I T O GeneralofItalyinSanFrancisco,andTheLeonardoda VinciSociety. CinemaItaliaSF.com N T O E N N S I E E Contact: Amelia Antonucci, Program Director [email protected] T O G A R R L R P P O Fiscalsponsor: TheLeonardoDaVinciSociety,501(c)(3)nonprofitorganization. A 0 0 0 0 Contributionsaretax-deductibletoextentoflaw. 0 0 0 0 0 , 0 0 0 0 , , , 1 5 2 1 $ $ $ $ Logo in Program Brochure, on Website (Linked) and On-Screen in Pre-Show Slideshow 4444 Display of Literature on Resource Table 4444 Tickets to Spotlight Film & the Party 248 16 Festival Passes (each good for all screenings and the party) 248 16 Adopt -

National Gallery of Art

ADMIION I FR DIRCTION 10:00 TO 5:00 National Gallery of Art Release Date: Jul 29, 2015 Summer Films at National Gallery of Art Include Albert Maysles Retrospective, Rare 35mm Prints from Italian Film Archives, Tribute to Titanus Studio, and Special Appearance by Indie Filmmaker Film still from Il idone Federico Fellini, 1955, to e screened as part of the series Titanus Presents: A Famil Chronicle of Italian Cinema, on August 23, National Galler of Art, ast uilding Auditorium. Image courtes of Titanus. Washington, DC—The National Galler of Art film program returns to its ast uilding Auditorium on August 1 with a triute to Alert Masles that focuses on his and his rother David's interest in art and performance and includes several screenings from Italian film archives shown in the Galler's annual summer preservation series dedicated this ear to the Italian film production house Titanus. Masles Films Inc.: Performing Vérité (some in original 16mm format) Through August 2 Alert Masles (1926–2015) and his rother David (1931–1987) expanded the artistic possiilities for direct cinema espousing "the ee of the poet" as a factor in shooting and editing cinema vérité. Their trademark approach—capturing action spontaneousl and avoiding a point of view—ecame, for a time, the ver definition of documentar. It is presented as a triute to Alert Masles, who died this ear in March. Masles often visited the National Galler of Art; his wife, Gillian Walker, was the daughter of former Galler director John Walker. The National Galler of Art extends a special thanks to Jake Perlin and Reekah Males for making the showing of the Masles films possile. -

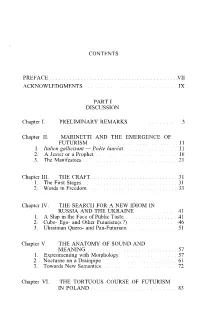

Contents Preface Vii Acknowledgments Ix Part I

CONTENTS PREFACE VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX PART I DISCUSSION Chapter I. PRELIMINARY REMARKS 3 Chapter II. MARINETTI AND THE EMERGENCE OF FUTURISM 11 1. Italien gallicisant — Poète lauréat 11 2. A Jester or a Prophet 16 3. The Manifestoes 21 Chapter III. THE CRAFT 31 1. The First Stages 31 2. Words in Freedom 33 Chapter IV. THE SEARCH FOR A NEW IDIOM IN RUSSIA AND THE UKRAINE 41 1. A Slap in the Face of Public Taste 41 2. Cubo- Ego- and Other Futurism(s ?) 46 3. Ukrainian Quero- and Pan-Futurism 51 Chapter V. THE ANATOMY OF SOUND AND MEANING 57 1. Experimenting with Morphology 57 2. Nocturne on a Drainpipe 61 3. Towards New Semantics 72 Chapter VI. THE TORTUOUS COURSE OF FUTURISM IN POLAND 83 XII FUTURISM IN MODERN POETRY Chapter VII. THE FURTHER EXPANSION OF THE FUTURIST IDEAS 97 1. Futurism in Czech and Slovak Poetry 97 2. Slovenia 102 3. Spain and Portugal 107 4. Brazil 109 Chapter VIII. CONCLUSION 117 PART II A SELECTION OF FUTURIST POETRY I. ITALY 125 A. FREE VERSE 125 Libero Altomare Canto futurista 126 A Futurist Song 127 A un aviatore 130 To an Aviator 131 Enrico Cardile Ode alia violenza 134 Ode to Violence 135 Enrico Cavacchioli Fuga in aeroplano 142 Flight in an Aeroplane 143 Auro D'Alba II piccolo re 146 The Little King 147 Luciano Folgore L'Elettricità 150 Electricity 151 F.T. Marinetti À l'automobile de course 154 To a Racing Car 155 Armando Mazza A Venezia 158 To Venice 159 Aldo Palazzeschi E lasciatemi divertire 164 And Let Me Have Fun 165 B. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

DINO RISI I Mostri? Sono Quelli Che Nascono in Tv

ATTUALITÀ GRANDI VECCHI PARLA DINO RISI I mostri? Sono quelli che nascono in tv Era uno psichiatra, l foglio bianco av- Intervista sorpasso e Profumo di donna, che squaderna sotto gli occhi con gelosa de- poi è diventato il padre volge il rullo del- ebbe due nomination all’Oscar, licatezza. È il campionario umano da cui Ila Olivetti Studio non riesce più a fermarsi, come sono nati i suoi film: «Suocera in fuga della commedia. 46, pronto a raccogliere una se fosse rimasto prigioniero di uno dei con la nuora sedicenne», «Eletto mister Oggi, alla soglia trama, un’invettiva, un ri- suoi film a episodi. È questa l’arte di Ri- Gay e la famiglia scopre la verità», «A cordo, ma nessuno può di- si, medico psichiatra convertito al cine- Villar Perosa due nomadi sorpresi in ca- dei 90 anni, il regista re se prima di sera sarà ne- ma, è questo che ha sempre fatto delle sa Agnelli», «Il killer s’innamora: don- spiega come vede ro d’inchiostro. Un quadro staccato dal- nostre esistenze: un collage apparente- na salva». Pubblicità di Valentino. I to- questa Italia 2006. la parete ha lasciato l’ombra sulla tap- mente senza senso, un puzzle strava- pless statuari di Sabrina Ferilli, Saman- pezzeria e il regista Dino Risi s’è risol- gante dove alla fine ogni tessera va a oc- tha De Grenet, Martina Colombari. Dai politici a Vallettopoli... to a coprire l’alone di polvere con un cupare il posto esatto assegnatole dal L’imprenditore Massimo Donadon che di STEFANO LORENZETTO patchwork di 21 immagini ritagliate dai grande mosaicista dell’universo o dal dà la caccia ai topi e il serial killer Gian- giornali. -

FILM POSTER CENSORSHIP by Maurizio Cesare Graziosi

FILM POSTER CENSORSHIP by Maurizio Cesare Graziosi The first decade of the twentieth century was the golden age of Italian cinema: more than 500 cinema theatres in the country, with revenues of 18 million lire. However, the nascent Italian “seventh art” had to immediately contend with morality, which protested against the “obsolete vulgarity of the cinema”. Thus, in 1913 the Giolitti government set up the Ufficio della Revisione Cinematografica (Film Revision Office). Censorship rhymes with dictatorship. However, during the twenty years of Italian Fascism, censorship was not particularly vigorous. Not out of any indulgence on the part of the black-shirted regime, but more because self-censorship is much more powerful than censorship. Therefore, in addition to the existing legislation, the Testo Unico delle Leggi di Pubblica Sicurezza (Consolidation Act on Public Safety Laws - R.D. 18 June 1931, n° 773) was sufficient. And so, as far as film poster censorship is concerned, the first record dates from the period immediately after the Second World War, in spring 1946, due to the censors’ intervention in posters for the re-release of La cena delle beffe (1942) by Alessandro Blasetti, and Harlem (1943) by Carmine Gallone. In both cases, it was ordered that the name of actor Osvaldo Valenti be removed, and for La cena delle beffe, the name of actress Luisa Ferida too. Osvaldo Valenti had taken part in the Social Republic of Salò and, along with Luisa Ferida, he was sentenced to death and executed on 30 April 1945. This, then, was a case which could be defined as a “censorship of purgation”. -

129 Film Proiettati in 20 Anni. Tante Pellicole Restaurate Per Raccontare L'italia, La Sua Storia, Il Suo Costume, La Sua Cult

1995-2014 129 film proiettati in 20 anni. Tante pellicole restaurate per raccontare l’Italia, la sua storia, il suo costume, la sua cultura. ..................................................................................................................................... Giuliano Montaldo racconta Giuliano Montaldo Ce l’abbiamo fatta. Abbiamo compiuto vent’anni Alberto Crespi Le vie del Cinema nascono a Narni come progetto d’identità Comune di Narni Le vie del Cinema anno per anno tutti i film Archivio Città di Narni Narni. Le vie del cinema XX Edizione, arrivederci. Archivio Le vie del Cinema Roma luglio 2014 Segreteria organizzativa Direttore srtistico, Ufficio Stampa Alberto Crespi Vic Comunicazione, Roma, Comune di Narni VIC Communication Piazza dei Priori, 1 Con il contributo [email protected] 05035 Narni (Tr) del Centro Sperimentale [email protected] di Cinematografia Design leviedelcinema@ comune.narni.tr.it www.fondazionecsc.it/ Bonifacio Pontonio © ANDREA BELLINELLI ..................................................................................................................................... L’idea nasce grazie al Sindaco di Narni Luigi Annesi e, con passione ed entusiasmo, Giuliano Montaldo racconta: sostenuta da Stefano Bigaroni e dall’attuale Sindaco Francesco De Rebotti. L’idea di restaurare e conservare i tanti capolavori del nostro Cinema La strada pincipale che attraversa Narni Scalo l’aveva lanciata Walter Veltoni e Narni sarà protagonista di un prezioso lavoro: è rumorosa per l’intenso traffico ma dopo salvare dal degrado i mitici film “La presa del potere da parte di Luigi XIV” un centinaio di metri, al lato di questa strada, di Roberto Rossellini e “Ladri di biciclette” di Vittorio De Sica. Affascinato si arriva in un vasto parco alberato, da questa iniziativa ho cercato di contribuire anch’io nella ricerca delle opere “Il parco dei pini” accolti da un magico silenzio. -

Cubism Futurism Art Deco

20TH Century Art Early 20th Century styles based on SHAPE and FORM: Cubism Futurism Art Deco to show the ‘concept’ of an object rather than creating a detail of the real thing to show different views of an object at once, emphasizing time, space & the Machine age to simplify objects to their most basic, primitive terms 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Pablo Picasso 1881-1973 Considered most influential artist of 20th Century Blue Period Rose Period Analytical Cubism Synthetic Cubism 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Early works by a young Picasso Girl Wearing Large Hat, 1901. Lola, the artist’s sister, 1901. 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Blue Period (1901-1904) Moves to Paris in his late teens Coping with suicide of friend Paintings were lonely, depressing Major color was BLUE! 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Blue Nude, 1902. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Self Portrait, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Tragedy, 1903. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Le Gourmet, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s work at the National Gallery (DC) 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Rose Period (1904-1906) Much happier art than before Circus people as subjects Reds and warmer colors Pablo Picasso, Harlequin Family, 1905. ROSE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Pablo Picasso, La Familia de Saltimbanques, 1905.