Downloaded 2021-09-26T23:35:06Z

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Legacy of Futurism's Obsession with Speed in 1960S

Deus (ex) macchina: The Legacy of Futurism’s Obsession with Speed in 1960s Italy Adriana M. Baranello University of California, Los Angeles Il Futurismo si fonda sul completo rinnovamento della sensibilità umana avvenuto per effetto delle grandi scoperte scientifiche.1 In “Distruzione di sintassi; Imaginazione senza fili; Parole in lib- ertà” Marinetti echoes his call to arms that formally began with the “Fondazione e Manifesto del Futurismo” in 1909. Marinetti’s loud, attention grabbing, and at times violent agenda were to have a lasting impact on Italy. Not only does Marinetti’s ideology reecho throughout Futurism’s thirty-year lifespan, it reechoes throughout twentieth-century Italy. It is this lasting legacy, the marks that Marinetti left on Italy’s cultural subconscious, that I will examine in this paper. The cultural moment is the early Sixties, the height of Italy’s boom economico and a time of tremendous social shifts in Italy. This paper will look at two specific examples in which Marinetti’s social and aesthetic agenda, par- ticularly the nuova religione-morale della velocità, speed and the car as vital reinvigorating life forces.2 These obsessions were reflected and refocused half a century later, in sometimes subtly and sometimes surprisingly blatant ways. I will address, principally, Dino Risi’s 1962 film Il sorpasso, and Emilio Isgrò’s 1964 Poesia Volkswagen, two works from the height of the Boom. While the dash towards modernity began with the Futurists, the articulation of many of their ideas and projects would come to frui- tion in the Boom years. Leslie Paul Thiele writes that, “[b]reaking the chains of tradition, the Futurists assumed, would progressively liberate humankind, allowing it to claim its birthright as master of its world.”3 Futurism would not last to see this ideal realized, but parts of their agenda return continually, and especially in the post-war period. -

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on Iitaly.Org (

Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Natasha Lardera (February 21, 2014) On view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, until September 1st, 2014, this thorough exploration of the Futurist movement, a major modernist expression that in many ways remains little known among American audiences, promises to show audiences a little known branch of Italian art. Giovanni Acquaviva, Guillaume Apollinaire, Fedele Azari, Francesco Balilla Pratella, Giacomo Balla, Barbara (Olga Biglieri), Benedetta (Benedetta Cappa Marinetti), Mario Bellusi, Ottavio Berard, Romeo Bevilacqua, Piero Boccardi, Umberto Boccioni, Enrico Bona, Aroldo Bonzagni, Anton Giulio Bragaglia, Arturo Bragaglia, Alessandro Bruschetti, Paolo Buzzi, Mauro Camuzzi, Francesco Cangiullo, Pasqualino Cangiullo, Mario Carli, Carlo Carra, Mario Castagneri, Giannina Censi, Cesare Cerati, Mario Chiattone, Gilbert Clavel, Bruno Corra (Bruno Ginanni Corradini), Tullio Crali, Tullio d’Albisola (Tullio Mazzotti), Ferruccio Demanins, Fortunato Depero, Nicolaj Diulgheroff, Gerardo Dottori, Fillia (Luigi Page 1 of 3 Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe Published on iItaly.org (http://www.iitaly.org) Colombo), Luciano Folgore (Omero Vecchi), Corrado Govoni, Virgilio Marchi, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Alberto Martini, Pino Masnata, Filippo Masoero, Angiolo Mazzoni, Torido Mazzotti, Alberto Montacchini, Nelson Morpurgo, Bruno Munari, N. Nicciani, Vinicio Paladini -

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity

The Train and the Cosmos: Visionary Modernity Matilde Marcolli 2015 • Mythopoesis: the capacity of the human mind to spontaneously generate symbols, myths, metaphors, ::: • Psychology (especially C.G. Jung) showed that the human mind (especially the uncon- scious) continuously generates a complex lan- guage of symbols and mythology (archetypes) • Religion: any form of belief that involves the supernatural • Mythopoesis does not require Religion: it can be symbolic, metaphoric, lyrical, visionary, without any reference to anything supernatural • Visionary Modernity has its roots in the Anarcho-Socialist mythology of Progress (late 19th early 20th century) and is the best known example of non-religious mythopoesis 1 Part 1: Futurist Trains 2 Trains as powerful symbol of Modernity: • the world suddenly becomes connected at a global scale, like never before • trains collectively drive humankind into the new modern epoch • connected to another powerful symbol: electricity • importance of the train symbolism in the anarcho-socialist philosophy of late 19th and early 20th century (Italian and Russian Futurism avant garde) 3 Rozanova, Composition with Train, 1910 4 Russolo, Dynamism of a Train, 1912 5 From a popular Italian song: Francesco Guccini \La Locomotiva" ... sembrava il treno anch'esso un mito di progesso lanciato sopra i continenti; e la locomotiva sembrava fosse un mostro strano che l'uomo dominava con il pensiero e con la mano: ruggendo si lasciava indietro distanze che sembravano infinite; sembrava avesse dentro un potere tremendo, la stessa forza della dinamite... ...the train itself looked like a myth of progress, launched over the continents; and the locomo- tive looked like a strange monster, that man could tame with thought and with the hand: roaring it would leave behind seemingly enor- mous distances; it seemed to contain an enor- mous might, the power of dynamite itself.. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

Sintesi Futurista Della Guerra

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Ugo Piatti SINTESI FUTURISTA El Lissitzky DELLA GUERRA SVENJA WEIKINNIS Schlagt die Weißen mit dem Roten Keil Faltblatt, Offsetdruck auf Papier, 29 x 23 cm, 1914 1919 Farblithografie 49,3 x 69,1 cm Russische Staat- »Marinetti, Boccioni, Carrà, Russolo, Piatti. Dal Cellulare di Milano, 20 Settembre Die Komposition des Diagramms erinnert an das Plakat Schlagt die Weißen mit dem liche Bibliothek, 1914«, mit dieser ungewöhnlichen Verortung geben die fünf Autoren des Flugblat- roten Keil von El Lissitzky, dessen avantgardistische und einprägsame Darstellung seit- Moskau tes sich zu erkennen. Bei einer interventionistischen Kundgebung in Mailand war die her mannigfaltig adaptiert wurde. Lissitzky propagierte mit ihm den russischen Bürger- Gruppe aus Künstlern und Literaten des Futurismus verhaftet worden. Als der Krieg krieg von Seiten der Roten Armee. Sein Plakat ist aber erst 1920 veröffentlicht worden, 1914 ausbrach, zögerte die italienische Regierung, sich zu beteiligen, stand sogar im weshalb die Möglichkeit besteht, dass Lissitzky die Formensprache von Sintesi futu- Bündnis mit Deutschland und Österreich. Die sogenannten »Interventisten«, deren Un- rista della guerra weiterentwickelt hat. Durch die analoge Gestaltung präzisiert sich die terstützer aus verschiedenen politischen Lagern kamen, drängten zum Kriegsbeitritt, Bildsprache beim Aufruf der futuristischen Gruppe: Der »Futurismo« dringt als Keil Künstler und Intellektuelle übernahmen eine wichtige Rolle bei dem Versuch, Kriegs- weit in den Kreis des »Passatismo« vor, um ihn aufzuspalten. Die Größenverhältnisse begeisterung in der Öffentlichkeit zu schüren. Im Gefängnis – so heißt es – entwarfen der Worte lassen keinen Zweifel offen, wer die Übermacht in diesem Krieg auf seiner die militanten Futuristen diese Proklamation in diagrammatischer Form. -

La Storia Del Cappello Alpino

La storia del cappello alpino ‘Onestà e solidarietà, queste le nostre regole’ E’ il motto della ‘86esima Adunata Nazionale Alpini’, la festa di popolo’ che con entusiasmo, competenza e efficienza si sta avviando verso il traguardo piacentino dei giorni 10-11-12 maggio. Come annunciato anche il nostro Portale offre ampia visibilità alla manifestazione con aneddoti, curiosità e con immagini originali o restaurate da Oreste Grana e Camillo Murelli. Oggi parliamo del Cappello Alpino rielaborando testi tratti da ‘Centomila gavette di ghiaccio’ di G. Bedeschi e da altre fonti. IL NOSTRO CAPPELLO ALPINO L’elemento più rappresentativo degli alpini è senza ombra di dubbio il cappello. È formato da molti elementi che rappresentano il grado, il reggimento, il battaglione, e la specialità di appartenenza. Nel 1873 gli alpini per differenziarsi dal chepì usato dai fanti, adottarono un proprio cappello di feltro nero a forma tronco conica a falda larga; sulla fronte aveva come fregio una stella a cinque punte metallica bianca, con inciso il numero della compagnia. Sul lato sinistro, vi era una coccarda tricolore con, al centro un bottoncino bianco con croce scanalata. Un rosso gallone a V rovesciata decorava il cappello sullo stesso lato della coccarda e sotto questa era infilata una penna nera di corvo. Gli ufficiali portavano lo stesso cappello, ma la penna era d’aquila. Nel 1880 la stella a cinque punte venne sostituita da un fregio metallico bianco: un’aquila che sormontava una cornetta contenente il numero di battaglione. La cornetta si trovava sopra un trofeo di fucili incrociati con baionetta innestata, una piccozza e una scure circondati da una corona di foglie di alloro e quercia. -

Music, Noise, and Abstraction

BYVASIL y KAND INSKY' s OWN AC co u NT, his proto-abstract canvas ImpressionIII (Konzert) (19n; plate 13) was directly inspired by a performance of Arnold Schoenberg's first atonal works (the Second String Quartet, op. ro, and the Three Piano Pieces, op. n) at a concert in Munich on January 2, r9n, attended by Kandinsky and his Blaue Reiter compatriots (plate 6). The correspondence that Kandinsky launched with Schoenberg in the days following the concert makes it clear that both the painter and the composer saw direct parallels between the abandonment of tonality in music and the liberation from representation in visual art. 1 That both construed these artistic breakthroughs in spiritual terms is equally clear. Responding to the crisis of value prompted by scientific mate rialism, Kandinsky and Schoenberg affirmed an inner, spiritual realm that promised "ascent to a higher and better order," as Schoenberg would later put it. 2 Kandinsky looked to music, "the least material of the arts," as a means to "turn away from the soulless content of modern life, toward materials and environments that give a free hand to the nonmaterial strivings and searchings of the thirsty soul." "Schoenberg's music," he insisted, "leads us into a new realm, where musical experiences are no longer acoustic, but purely spiritua/."3 But what constitutes the "abstraction" of music in general and of atonal music in particular? And might this well-worn story obscure alternative conceptions of "abstraction" and other relationships between music and art in European modernism? Contrary to the self-presentations of Schoenberg and Kandinsky, there is nothing fundamental about the analogy between abstraction and atonality which is why Paul Klee, Frantisek Kupka, Marsden Hartley, and many other early abstract painters could find inspiration in the eighteenth-century polyphony that consolidated the tonal system in the first place. -

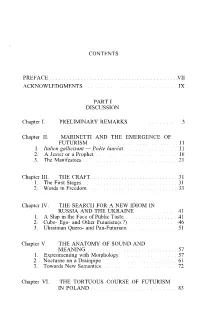

Contents Preface Vii Acknowledgments Ix Part I

CONTENTS PREFACE VII ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX PART I DISCUSSION Chapter I. PRELIMINARY REMARKS 3 Chapter II. MARINETTI AND THE EMERGENCE OF FUTURISM 11 1. Italien gallicisant — Poète lauréat 11 2. A Jester or a Prophet 16 3. The Manifestoes 21 Chapter III. THE CRAFT 31 1. The First Stages 31 2. Words in Freedom 33 Chapter IV. THE SEARCH FOR A NEW IDIOM IN RUSSIA AND THE UKRAINE 41 1. A Slap in the Face of Public Taste 41 2. Cubo- Ego- and Other Futurism(s ?) 46 3. Ukrainian Quero- and Pan-Futurism 51 Chapter V. THE ANATOMY OF SOUND AND MEANING 57 1. Experimenting with Morphology 57 2. Nocturne on a Drainpipe 61 3. Towards New Semantics 72 Chapter VI. THE TORTUOUS COURSE OF FUTURISM IN POLAND 83 XII FUTURISM IN MODERN POETRY Chapter VII. THE FURTHER EXPANSION OF THE FUTURIST IDEAS 97 1. Futurism in Czech and Slovak Poetry 97 2. Slovenia 102 3. Spain and Portugal 107 4. Brazil 109 Chapter VIII. CONCLUSION 117 PART II A SELECTION OF FUTURIST POETRY I. ITALY 125 A. FREE VERSE 125 Libero Altomare Canto futurista 126 A Futurist Song 127 A un aviatore 130 To an Aviator 131 Enrico Cardile Ode alia violenza 134 Ode to Violence 135 Enrico Cavacchioli Fuga in aeroplano 142 Flight in an Aeroplane 143 Auro D'Alba II piccolo re 146 The Little King 147 Luciano Folgore L'Elettricità 150 Electricity 151 F.T. Marinetti À l'automobile de course 154 To a Racing Car 155 Armando Mazza A Venezia 158 To Venice 159 Aldo Palazzeschi E lasciatemi divertire 164 And Let Me Have Fun 165 B. -

Armiero, Marco. a Rugged Nation: Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy

The White Horse Press Full citation: Armiero, Marco. A Rugged Nation: Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy. Cambridge: The White Horse Press, 2011. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/3501. Rights: All rights reserved. © The White Horse Press 2011. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. For further information please see http://www.whpress.co.uk. A Rugged Nation Marco Armiero A Rugged Nation Mountains and the Making of Modern Italy: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries The White Horse Press Copyright © Marco Armiero First published 2011 by The White Horse Press, 10 High Street, Knapwell, Cambridge, CB23 4NR, UK Set in 11 point Adobe Garamond Pro Printed by Lightning Source All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying or recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-874267-64-5 But memory is not only made by oaths, words and plaques; it is also made of gestures which we repeat every morning of the world. And the world we want needs to be saved, fed and kept alive every day. -

Futurism-Anthology.Pdf

FUTURISM FUTURISM AN ANTHOLOGY Edited by Lawrence Rainey Christine Poggi Laura Wittman Yale University Press New Haven & London Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Published with assistance from the Kingsley Trust Association Publication Fund established by the Scroll and Key Society of Yale College. Frontispiece on page ii is a detail of fig. 35. Copyright © 2009 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Nancy Ovedovitz and set in Scala type by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Futurism : an anthology / edited by Lawrence Rainey, Christine Poggi, and Laura Wittman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-08875-5 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Futurism (Art) 2. Futurism (Literary movement) 3. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Rainey, Lawrence S. II. Poggi, Christine, 1953– III. Wittman, Laura. NX456.5.F8F87 2009 700'.4114—dc22 2009007811 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: F. T. Marinetti and the Development of Futurism Lawrence Rainey 1 Part One Manifestos and Theoretical Writings Introduction to Part One Lawrence Rainey 43 The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909) F. -

Cubism Futurism Art Deco

20TH Century Art Early 20th Century styles based on SHAPE and FORM: Cubism Futurism Art Deco to show the ‘concept’ of an object rather than creating a detail of the real thing to show different views of an object at once, emphasizing time, space & the Machine age to simplify objects to their most basic, primitive terms 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Pablo Picasso 1881-1973 Considered most influential artist of 20th Century Blue Period Rose Period Analytical Cubism Synthetic Cubism 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Early works by a young Picasso Girl Wearing Large Hat, 1901. Lola, the artist’s sister, 1901. 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Blue Period (1901-1904) Moves to Paris in his late teens Coping with suicide of friend Paintings were lonely, depressing Major color was BLUE! 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Blue Nude, 1902. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Self Portrait, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Tragedy, 1903. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Blue Period Pablo Picasso, Le Gourmet, 1901. BLUE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s work at the National Gallery (DC) 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Rose Period (1904-1906) Much happier art than before Circus people as subjects Reds and warmer colors Pablo Picasso, Harlequin Family, 1905. ROSE PERIOD 20TH CENTURY ART & ARCHITECTURE Cubism & Picasso Picasso’s Rose Period Pablo Picasso, La Familia de Saltimbanques, 1905. -

Italian 6Th Army in Albania, 15 October 1940

Italian 6th Army in Albania 15 October 1940 6TH ARMY "PO" Army Troops: 178th (mot) CC.RR. Section 353rd Celere CC.RR. Section Photographic Squadron Topographiocal Section 141st Field Hospital 142nd Field Hospital 143rd Field Hospital 144th Field Hospital 160th Field Hospital 501st Field Hospital 106th Recovery Section 94th Supply (Sustenance) Section 17th Veterinary Hospital 124th Veterinary Hospital Armored Corps: Corps Troops Headquarters Command Motorized Platoon Road Movement Detachment Road Recover Detachment Heavy Fuel Section Artillery Topographical Section 132nd "Ariete" Armored Division Headquarters Detachment 132nd Armored Regimental Headquarters 7th Armored Battalion (M13 Tanks) 8th Armored Battalion (M13 Tanks) 9th Armored Battalion (M13 Tanks) 8th Bersaglieri Regiment Motorized Headquarters Company 12th Motorized Bersaglieri Battalion, with 1 Motorized Headquarters Company 2 Motorized Bersaglieri Companies 1 Motorized Anti-Tank Company (8-47mm guns) 5th Motorized Bersaglieri Battalion, with 1 Motorized Headquarters Company 2 Motorized Bersaglieri Companies 1 Motorized Anti-Tank Company (8-47mm guns) 3rd Heavy Weapons Battalion, with 1 Motorized Headquarters Company 1 Motorized Machine Gun Company 1 Motorized Anti-Aircraft Company (20mm Guns) 1 Motorized Mortar Company (81mm Mortars) 1 Motorcycle Company 1 Motorized Engineer Battalion (in Italy) 1 Motorized Anti-Tank Battalion, with 1 Motorized Headquarters Company 2 Motorized Anti-Tank Companies (8-47mm/32 Guns) 132nd Motorized Artillery Regiment 1 1 Motorized Anti-Aircraft