The Torres Strait: a Case Study Analysis in Multi-Level Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company The geology of the Mabuyag Island Group and its part in the geological evolution of Torres Strait Friedrich VON GNIELINSKI von Gnielinski, F. -

Sociality and Locality in a Torres Strait Community

Past Visions, Present Lives: sociality and locality in a Torres Strait community. Thesis submitted by Julie Lahn BA (Hons) (JCU) November 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make it available for use within the University Library and, by microfilm or other means, allow access to users in other approved libraries. All users consulting this thesis will have to sign the following statement: In consulting this thesis I agree not to copy or closely paraphrase it in whole or in part without the written consent of the author; and to make proper public written acknowledgment for any assistance that I have obtained from it. Beyond this, I do not wish to place any restriction on access to this thesis. _________________________________ __________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Acknowledgments My main period of fieldwork was conducted over fifteen months at Warraber Island between July 1996 and September 1997. I am grateful to many Warraberans for their assistance and generosity both during my main fieldwork and subsequent visits to the island. -

Guidelines for Preparing and Assessing Connection Material for Native Title Claims in Queensland

Guidelines for preparing and assessing connection material for Native Title Claims in Queensland November 2016 This publication has been compiled by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Services, Department of Natural Resources and Mines. © State of Queensland, 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Table of contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 2 The connection material to be provided to the State ............................................................... 4 3 The contents -

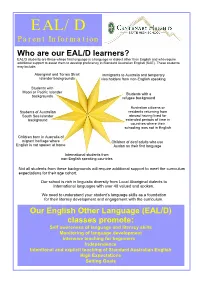

EALD Information (PDF, 434

EAL/D Parent Information Who are our EAL/D learners? EAL/D students are those whose first language is a language or dialect other than English and who require additional support to assist them to develop proficiency in Standard Australian English (SAE). These students may include: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Immigrants to Australia and temporary Islander backgrounds visa holders from non-English speaking Students with Maori or Pacific Islander Students with a backgrounds refugee background Australian citizens or Students of Australian residents returning from South Sea islander abroad having lived for background extended periods of time in countries where their schooling was not in English Children born in Australia of migrant heritage where Children of deaf adults who use English is not spoken at home Auslan as their first language International students from non-English speaking countries Not all students from these backgrounds will require additional support to meet the curriculum expectations for their age cohort. Our school is rich in linguistic diversity from Local Aboriginal dialects to International languages with over 40 valued and spoken. We need to understand your student’s language skills as a foundation for their literacy development and engagement with the curriculum. Our English Other Language (EAL/D) classes promote: Self awareness of language and literacy skills Monitoring of language development Intensive teaching for beginners Independence Intentional and explicit teaching of Standard Australian English High Expectations Setting Goals When schools know students speak other languages they can support students in engaging in their learning to reach their educational potential. The information on these questions allows for the right support for your student. -

Australian Notices to Mariners Are the Authority for Correcting Australian Charts and Publications AUSTRALIAN NOTICES to MARINERS Notices 329 - 373

25 March 2016 Edition 6 Australian Notices to Mariners are the authority for correcting Australian Charts and Publications AUSTRALIAN NOTICES TO MARINERS Notices 329 - 373 Published fortnightly by the Australian Hydrographic Service Commodore B.K. BRACE RAN Hydrographer of Australia SECTIONS. I. Australian Notices to Mariners, including blocks and notes. II. Hydrographic Reports. III. Navigational Warnings. SUPPLEMENTS. I. Tracings II. Cumulative List of Australian Notices to Mariners. III. Cumulative List of Temporary and Preliminary Australian Notices to Mariners. IV. Temporary and Preliminary Notices in force. V. Amendments to Admiralty List of Lights and Fog Signals (Vol K), Radio Signals (NP 281(2), 282, 283(2), 285, 286(4)) and Sailing Directions (NP 9, 13, 14, 15, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39, 44, 51, 60, 61, 62, 100, 136). © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process, adapted, communicated or commercially exploited without prior written permission from The Commonwealth represented by the Australian Hydrographic Service. AHP 18 IMPORTANT NOTICE This edition of Notices to Mariners includes all significant information affecting AHS products which the AHS has become aware of since the last edition. All reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information, including third party information, on which these updates are based. The AHS regards third parties from which it receives information as reliable, however the AHS cannot verify all such information and errors may therefore exist. The AHS does not accept liability for errors in third party information. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Inquiry Into Matters Relating to the Torres

-;C\h(1Qd ,tOUA"n" f i :~ -ioS:l.O.l:oi '" i IvIr Co 1'V1.[ _iQ( Ci Ta.bf;. e..cJ. C"fV] 17 D~c Zz.--Xy:=) /1 Pew"(!v~" ~ 'c> THE TORRES STRAIT TREATY: OCEAN BOUNDARY DELIMITATION BY AGREEMENT ../ By H, Burmester" INTRODUCTION The delimitation of maritime boundaries is one of the major areas of ocean law where disputes between countries occur with frequency and where the development of governing principles of law remains difficult, At the Law of the Sea Conference, delimitation of the continental shelf and economic zones between states with opposite or adjacent coasts was one of the last issues to be resolved.' Major judicial and arbitral decisions, such as the North Sea Conti- nental Shelf cases'' before the International Court of Justice and the Anglo- French Continental Shelf arbitration.l have gone some way to developing a body of relevant law to assist states in the solution of their maritime boundary problems. These decisions have clarified some of the relevant factors that states should take into account, but major boundary problems remain. On the Aegean Sea, Greece and Turkey have still not reached any solution;" relations between Canada and the United States have been severely strained by their slow progress on maritime boundary issuesf Libya and Tunisia have referred their conti- ., Faculty of Law, Australian National University. The author was formerly an officer of the Australian Attorney-General's Department and a member of the Australian negotiating team for the Torres Strait Treaty. 1 Arts, 74(1) and 83(1) of the Draft Convention on the Law of the Sea (Aug, 1981), UN Doc, A/CONF.62/L.78. -

Torres Strait Islanders: a New Deal

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: A NEW DEAL A REPORT ON GREATER AUTONOMY FOR TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Affairs August 1997 Canberra Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs and printed by AGPS Canberra. The cover was produced in the AGPS design studios. The graphic on the cover was developed from a photograph taken on Yorke/Masig Island during the Committee's visit in October 1996. CONTENTS FOREWORD ix TERMS OF REFERENCE xii MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE xiii GLOSSARY xiv SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS xv CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE.......................................................................................................................................1 CONDUCT OF THE INQUIRY ......................................................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF THE REPORT.............................................................................................................................................2 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................................................3 Commonwealth-State Cooperation ....................................................................................................................3 -

The Spread of Torres Strait Creole to the Central Islands Of

THE SPREAD OF TORRES STRAIT CREOLE TO THE CENTRAL ISLANDS OF TORRES STRAIT Anna Shnukal INTRODUCTION1 The following paper outlines the second stage of development of Torres Strait Creole, now the lingua franca, or common language, of Torres Strait Islanders everywhere.2 The first stage, which I discussed in an earlier volume of this journal, was that of the creolisation of Pacific Pidgin English around the turn of the century in three Torres Strait island commu nities.3 In that article, I argued that creolisation was the result of two factors not reproduced elsewhere in Torres Strait at the time: (1) the creation of de facto Pacific Islander settle ments on Erub, Ugar and St Paul’s Anglican Mission, Moa, where the Pacific Islanders out numbered Torres Strait Islanders and (2) the integration into those communities of these hitherto marginal immigrants. The prestige of the Pacific Islanders derived from their func tion as linguistic and cultural middlemen, interpreters of European ways of life to their Torres Strait Islander kinfolk. A third stage in the development of the creole began with the war years, when almost all able-bodied men left their home islands to join the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion and, for the first time, came into daily contact with English-speaking Europeans. The present overview article traces the diffusion of Pacific Pidgin English and the creole which developed from it, focusing on the central islands of the Strait between the early 1900s and the beginning of World War II. Also briefly discussed are certain interwoven historical Anna Shnukal carried out research into Torres Strait Creole while a Visiting Research Fellow in Socio linguistics at the Australian Institute o f Aboriginal Studies. -

The Torres Strait Islands: Constitutional and Sovereignty Questions Post- Mabo

The Torres Strait Islands: Constitutional and Sovereignty Questions Post- Mabo Stuart BKaye Tutor in Law, Faculty of Law, The University ofSydney.* 1. Background The Torres Strait Treaty1 is often cited by publicists as being one of the most creative maritime boundary agreements in the world. With its separation ofthe fisheries and sea bed jurisdiction lines, its unique Protected Zone which seeks to preserve the way of life of the traditional inhabitants of the region, and its allocation of fisheries resources,2 it is often held up as a model indicating the way complex issues can be resolved and en trenched points ofview satisfied in maritime boundary disputes. This article will seek to critically examine one relatively minor aspect of the Treaty, specifically Australian rec ognition of Papua New Guinea (PNG) sovereignty over three small islands in the north ofTorres Strait. Torres Strait separates the northern tip of the Australian continent, Cape York Penin sula,3 from the island of New Guinea, and is approximately seventy miles across. The Strait is dotted with small islands which are, virtually without exception, all under Aus tralian control. The quite sizeable and inhabited Australian islands ofSaibai and Boigu lie scarcely a mile or two off the PNG coast, separated by waters that are claimed by some to be so shallow as to pennit a person to wade from one country to the other. This curious situation came about last century, before British annexation of the south-east portion of the island of New Guinea, at a time when Queensland was most anxious to ensure the Strait would not fall under the control of another European power, as well as to protect the natives of the Torres Strait Islands from violence, and to prevent the islands being used to evade Queensland revenue and immigration law. -

277995 VACGAZ 14 Nov 03

Queensland Government Gazette PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. CCCXXXIV] FRIDAY, 14 NOVEMBER, 2003 belong in a new car? Key features: Fast approvals New vehicle or demo with 20% deposit (usually in 24 hours) p.a.* No on-going fees on 7.20% loan account Early payout option Comparison rate Loan pre-approval 1 Pay-by-the-month p.a.* insurance 7.45% Competitive rates CUAGA1003 Ask at your local CUA branch for more information. Or call CUA Direct on (07) 3365 0055. 1Comparison Rate calculated on a loan amount of $30,000 over a term of 5 years based on fortnightly repayments. These rates are for secured loans only. WARNING: This comparison rate applies only to the example or examples given. Different amounts and terms will result in different comparison rates. Costs such as redraw fees or early repayment fees, and cost savings such as fee waivers, are not included in the comparison rate but may influence the cost of the loan. Comparison Rate Schedules are available at all CUA branches, linked credit providers and on our website at www.cua.com.au. * Loans are subject to normal CUA lending criteria. Fees and charges apply. Full terms and conditions are available on application. www.cua.com.au [767] Queensland Government Gazette EXTRAORDINARY PP 451207100087 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ISSN 0155-9370 Vol. CCCXXXIV] MONDAY, 10 NOVEMBER, 2003 [No. 50 Queensland NOTIFICATION OF SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION Statutory Instruments Act 1992 Notice is given of the making of the subordinate legislation mentioned in Table 1 TABLE 1 SUBORDINATE LEGISLATION BY NUMBER No. -

1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2

TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY 1997~1998 ANNUAL REPORT 60011 Cover 16/11/98 2:43 PM Page 2 ©Commonwealth of Australia 1998 ISSN 1324–163X This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. Annual Report 1997~98 PUPUA NEW GUINEA SAIBAI ISLAND (Kaumag Is) BOIGU ISLAND UGAR (STEPHEN) ISLAND DAUAN ISLAND TORRES STRAIT DARNLEY ISLAND YAM ISLAND MASIG (YORKE) ISLAND MABUIAG ISLAND MER (MURRAY) ISLAND BADU ISLAND PORUMA (COCONUT) ISLAND ST PAULS WARRABER (SUE) ISLAND KUBIN MOA ISLAND HAMMOND ISLAND THURSDAY ISLAND (Port Kennedy, Tamwoy) HORN ISLAND PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND SEISIA BAMAGA CAPE YORK TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY © Commonwealth of Australia 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA). Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction rights should be directed to the Public Affairs Officer, TSRA, PO Box 261, Thursday Island, Queensland 4875. The artwork on the front cover was designed by Torres Strait Islander artist, Alick Tipoti. TORRES STRAIT REGIONAL AUTHORITY Senator the Hon. John Herron Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs Suite MF44 Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister In accordance with section 144ZB of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission Act 1989, I am delighted to present you with the fourth Annual Report of the Torres Strait Regional Authority (TSRA).