Inquiry Into Matters Relating to the Torres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Preparing and Assessing Connection Material for Native Title Claims in Queensland

Guidelines for preparing and assessing connection material for Native Title Claims in Queensland November 2016 This publication has been compiled by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Services, Department of Natural Resources and Mines. © State of Queensland, 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Table of contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 2 The connection material to be provided to the State ............................................................... 4 3 The contents -

Australian Notices to Mariners Are the Authority for Correcting Australian Charts and Publications AUSTRALIAN NOTICES to MARINERS Notices 329 - 373

25 March 2016 Edition 6 Australian Notices to Mariners are the authority for correcting Australian Charts and Publications AUSTRALIAN NOTICES TO MARINERS Notices 329 - 373 Published fortnightly by the Australian Hydrographic Service Commodore B.K. BRACE RAN Hydrographer of Australia SECTIONS. I. Australian Notices to Mariners, including blocks and notes. II. Hydrographic Reports. III. Navigational Warnings. SUPPLEMENTS. I. Tracings II. Cumulative List of Australian Notices to Mariners. III. Cumulative List of Temporary and Preliminary Australian Notices to Mariners. IV. Temporary and Preliminary Notices in force. V. Amendments to Admiralty List of Lights and Fog Signals (Vol K), Radio Signals (NP 281(2), 282, 283(2), 285, 286(4)) and Sailing Directions (NP 9, 13, 14, 15, 33, 34, 35, 36, 39, 44, 51, 60, 61, 62, 100, 136). © Commonwealth of Australia 2016 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process, adapted, communicated or commercially exploited without prior written permission from The Commonwealth represented by the Australian Hydrographic Service. AHP 18 IMPORTANT NOTICE This edition of Notices to Mariners includes all significant information affecting AHS products which the AHS has become aware of since the last edition. All reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information, including third party information, on which these updates are based. The AHS regards third parties from which it receives information as reliable, however the AHS cannot verify all such information and errors may therefore exist. The AHS does not accept liability for errors in third party information. -

The Torres Strait Islands: Constitutional and Sovereignty Questions Post- Mabo

The Torres Strait Islands: Constitutional and Sovereignty Questions Post- Mabo Stuart BKaye Tutor in Law, Faculty of Law, The University ofSydney.* 1. Background The Torres Strait Treaty1 is often cited by publicists as being one of the most creative maritime boundary agreements in the world. With its separation ofthe fisheries and sea bed jurisdiction lines, its unique Protected Zone which seeks to preserve the way of life of the traditional inhabitants of the region, and its allocation of fisheries resources,2 it is often held up as a model indicating the way complex issues can be resolved and en trenched points ofview satisfied in maritime boundary disputes. This article will seek to critically examine one relatively minor aspect of the Treaty, specifically Australian rec ognition of Papua New Guinea (PNG) sovereignty over three small islands in the north ofTorres Strait. Torres Strait separates the northern tip of the Australian continent, Cape York Penin sula,3 from the island of New Guinea, and is approximately seventy miles across. The Strait is dotted with small islands which are, virtually without exception, all under Aus tralian control. The quite sizeable and inhabited Australian islands ofSaibai and Boigu lie scarcely a mile or two off the PNG coast, separated by waters that are claimed by some to be so shallow as to pennit a person to wade from one country to the other. This curious situation came about last century, before British annexation of the south-east portion of the island of New Guinea, at a time when Queensland was most anxious to ensure the Strait would not fall under the control of another European power, as well as to protect the natives of the Torres Strait Islands from violence, and to prevent the islands being used to evade Queensland revenue and immigration law. -

Great Barrier Reef

PAPUA 145°E 150°E GULF OF PAPUA Dyke NEW GUINEA O Ackland W Bay GREAT BARRIER REEF 200 E Daru N S General Reference Map T Talbot Islands Anchor Cay A Collingwood Lagoon Reef N Bay Saibai Port Moresby L Reefs E G Island Y N E Portlock Reefs R A Torres Murray Islands Warrior 10°S Moa Boot Reef 10°S Badu Island Island 200 Eastern Fields (Refer Legend below) Ashmore Reef Strait 2000 Thursday 200 Island 10°40’55"S 145°00’04"E WORLD HERITAGE AREA AND REGION BOUNDARY ait Newcastle Bay Endeavour Str GREAT BARRIER REEF WORLD HERITAGE AREA Bamaga (Extends from the low water mark of the mainland and includes all islands, internal waters of Queensland and Seas and Submerged Lands Orford Bay Act exclusions.) Total area approximately 348 000 sq km FAR NORTHERN Raine Island MANAGEMENT AREA GREAT BARRIER REEF REGION CAPE Great Detached (Extends from the low water mark of the mainland but excludes lburne Bay he Reef Queensland-owned islands, internal waters of Queensland and Seas S and Submerged Lands Act exclusions.) Total area approximately 346 000 sq km ple Bay em Wenlock T GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK (Excludes Queensland-owned islands, internal waters of Queensland River G and Seas and Submerged Lands Act exclusions.) Lockhart 4000 Total area approximately 344 400 sq km Weipa Lloyd Bay River R GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK 12°59’55"S MANAGEMENT AREA E 145°00’04"E CORAL SEA YORK GREAT BARRIER REEF PROVINCE Aurukun River A (As defined by W.G.H. -

Prescribed Bodies Corporate Directory May 2017

Prescribed Bodies Corporate May Directory 2017 Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (TSI) Corporation RNTBC [ICN: 4583]1 Preferred method of Chair The Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation RNTBC communication: Maluwap Nona administers native title rights and interests on behalf of the people of Badu Email or phone call to Mr Ph: 0497643345 and Moa. Translated, the name means ‘Badu and Moa little islands’ and the Maluwap Nona and “cc: in John Email: determination area includes some 80 islands in the vicinity of Badu and Wigness [email protected] m Moa. Some of these islands are: Mailing Address: Parts of Matu (Whale Island) c/- TSIRC MER Deputy Chair Zurat (Phipps Island) MER, QLD, 4875 Saila Savage Kulbai (Spencer Island) Via Thursday Island QLD, 4875 Ph: 0400762194 Ngurtai (Quoin Island) Maitak (Wilson Island) Email: Treasurer chairperson.malulamar@gmail. Opeta James Kaitap Kanig (Duncan Island) com and Ph: 07 40694095 Ilapnab (Green Island) [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tukupai (Clarke Island) Ngul (Browne Island) Contact Person Tuin (Barney Island) John Wigness Ph: 07 4094833 Wia (High Island) Email: [email protected] Logan Rocks Gainaulai Directors: Tuft Rock Maluwap Nona Meth Islet Saila Savage Opeta James Kaitap Dadalai (Canoe Island) 1 Uninhabited Islands PBC; Inhabited Islands PBC; ICN= Indigenous Corporation Number ICN 1103 PBC Contact Information List ( Current as at 22 May 2017 ) Last Updated 22 May 2017 P a g e | 1 Prescribed Bodies Corporate May Directory -

Great Barrier Reef

145°E 150°E PAPUA GULF OF PAPUA Dyke 200 GREAT BARRIER REEF O Ackland NEW GUINEA W Bay E Daru N General Reference Map S Talbot Islands Anchor Cay T Collingwood A WORLD HERITAGE AREA AND REGION BOUNDARY Lagoon Reef N Bay Saibai Port Moresby Reefs L GREAT BARRIER REEF WORLD HERITAGE AREA Island E Y N G Portlock Reefs R A E (Extends from the low water mark of the mainland and includes all Torres islands, internal waters of Queensland and Seas and Submerged Lands arrior Murray Islands Act exclusions.) W 10°S Moa Boot Reef 10°S Badu Island Island Total area approximately 348 000 sq km 200 Eastern Fields (Refer Legend below) GREAT BARRIER REEF REGION Ashmore Reef Strait 2000 (Extends from the low water mark of the mainland but excludes Queensland-owned islands, internal waters of Queensland and Seas Thursday 200 and Submerged Lands Act exclusions.) Island 10°40’55"S 145 00’04"E t Newcastle Bay ° Total area approximately 346 000 sq km Endeavour Strai 1 Bamaga GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK (Comprises thirty three sections as per Proclamations but excludes Orford Bay Queensland-owned islands, internal waters of Queensland and Seas and Submerged Lands Act exclusions.) FAR NORTHERN SECTION Total area approximately 345 400 sq km 2 Raine Island CAPE Great Detached GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK SECTION burne Bay hel Reef (Refer Legend below) S 3 GREAT BARRIER REEF PROVINCE (As defined by W.G.H. Maxwell. Includes that part of the Queensland 4 mple Bay W e shelf that is occupied by reefs and reef-derived sediment.) enlock T Total area is estimated to be 283 000 sq km 5 4000 River G Lockhart 6 MAJOR CATCHMENT BOUNDARY Weipa Lloyd Bay River R 12°59’55"S E 145°00’04"E CORAL SEA THIS MAP IS INDICATIVE ONLY. -

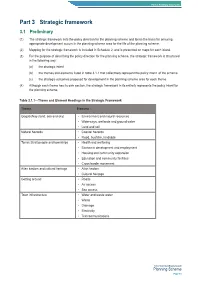

Part 3 Strategic Framework 3.1 Preliminary

Part 3: Strategic framework Part 3 Strategic framework 3.1 Preliminary (1) The strategic framework sets the policy direction for the planning scheme and forms the basis for ensuring appropriate development occurs in the planning scheme area for the life of the planning scheme. (2) Mapping for the strategic framework is included in Schedule 2, and is presented on maps for each island. (3) For the purpose of describing the policy direction for the planning scheme, the strategic framework is structured in the following way: (a) the strategic intent (b) the themes and elements listed in table 3.1.1 that collectively represent the policy intent of the scheme (c) the strategic outcomes proposed for development in the planning scheme area for each theme (4) Although each theme has its own section, the strategic framework in its entirety represents the policy intent for the planning scheme. Table 3.1.1—Theme and Element Headings in the Strategic Framework Theme Element Gogobithiay (land, sea and sky) • Environment and natural resources • Waterways, wetlands and ground water • Land and soil Natural hazards • Coastal hazards • )ORRGEXVK¿UHODQGVOLGH Torres Strait people and townships • Health and wellbeing • Economic development and employment • Housing and community expansion • Education and community facilities • Cross border movement Ailan kastom and cultural heritage • Ailan kastom • Cultural heritage Getting around • Roads • Air access • Sea access Town infrastructure • Water and waste water • Waste • Drainage • Electricity • Telecommunications Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 11 3.2 Gogobithiay (Land, Sea and Sky) Editor’s Note – Gogobithiay (land, sea and sky) is fundamental to the Torres Strait Islander way of life. -

Prescribed Bodies Corporate Directory March 2017

Prescribed Bodies Corporate March Directory 2017 Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (TSI) Corporation RNTBC [ICN: 4583]1 Preferred method of Chair The Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation RNTBC communication: Maluwap Nona administers native title rights and interests on behalf of the people of Badu Email or phone call to Mr Ph: 0497643345 and Moa. Translated, the name means ‘Badu and Moa little islands’ and the Maluwap Nona and “cc: in John Email: determination area includes some 80 islands in the vicinity of Badu and Wigness [email protected] m Moa. Some of these islands are: Mailing Address: Parts of Matu (Whale Island) c/- TSIRC MER Deputy Chair Zurat (Phipps Island) MER, QLD, 4875 Saila Savage Kulbai (Spencer Island) Via Thursday Island QLD, 4875 Ph: 0400762194 Ngurtai (Quoin Island) Maitak (Wilson Island) Email: Treasurer chairperson.malulamar@gmail. Opeta James Kaitap Kanig (Duncan Island) com and Ph: 07 40694095 Ilapnab (Green Island) [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tukupai (Clarke Island) Ngul (Browne Island) Contact Person Tuin (Barney Island) John Wigness Ph: 07 4094833 Wia (High Island) Email: [email protected] Logan Rocks Gainaulai Directors: Tuft Rock Maluwap Nona Meth Islet Saila Savage Opeta James Kaitap Dadalai (Canoe Island) 1 Uninhabited Islands PBC; Inhabited Islands PBC; ICN= Indigenous Corporation Number ICN 1103 PBC Contact Information List ( Current as at 3 March 2017 ) Last Updated 6 March 2017 P a g e | 1 Prescribed Bodies Corporate March Directory -

Prescribed Bodies Corporate Directory June 2017

Prescribed Bodies Corporate June Directory 2017 Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (TSI) Corporation RNTBC [ICN: 4583]1 Preferred method of Chair The Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation RNTBC communication: Maluwap Nona administers native title rights and interests on behalf of the people of Badu Email or phone call to Mr Ph: 0497643345 and Moa. Translated, the name means ‘Badu and Moa little islands’ and the Maluwap Nona and “cc: in John Email: determination area includes some 80 islands in the vicinity of Badu and Wigness [email protected] m Moa. Some of these islands are: Mailing Address: Parts of Matu (Whale Island) c/- TSIRC MER Deputy Chair Zurat (Phipps Island) MER, QLD, 4875 Saila Savage Kulbai (Spencer Island) Via Thursday Island QLD, 4875 Ph: 0400762194 Ngurtai (Quoin Island) Maitak (Wilson Island) Email: Treasurer chairperson.malulamar@gmail. Opeta James Kaitap Kanig (Duncan Island) com and Ph: 07 40694095 Ilapnab (Green Island) [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tukupai (Clarke Island) Ngul (Browne Island) Contact Person Tuin (Barney Island) John Wigness Ph: 07 4094833 Wia (High Island) Email: [email protected] Logan Rocks Gainaulai Directors: Tuft Rock Maluwap Nona Meth Islet Saila Savage Opeta James Kaitap Dadalai (Canoe Island) 1 Uninhabited Islands PBC; Inhabited Islands PBC; ICN= Indigenous Corporation Number ICN 1103 PBC Contact Information List ( Current as at 22 May 2017 ) Last Updated 15 June 2017 P a g e | 1 Prescribed Bodies Corporate June Directory -

Seabed & Fisheries Jurisdiction Lines Seabed Jurisdiction Line Marine

Australia's Maritime Zones in the Torres Strait 141°15’E 141°30’E 142°00’E 142°30’E 143°00’E 143°30’E 144°00’E 144°30’E 9°00’S Katatai Parama 9°00’S Parama I Papua New Guinea Daru Not to be Used For Navigation Torze Masingara Ture Ture SCALE 1:300 000 at lat 27°15’S Bramble Cay Buji Mawatta Bobo I Projection: Mercator Moibut Ber Positions are related to Mari Black Rks Australian Geodetic Datum (1966) Jarai Mata Kawa I Kussa I Kawa I Aubussi I ONE Moimi I CTED Z PROTE E Boigu Island Mabaduan N TALBO ZO T ISLA Sigabaduru ED NDS Auwamaza CT E Kaumag I Reef A Anchor Cay OT PR PAPUA NEW GUINE Saibai Island East Cay r Dauan I o AUSTRALIA i s r f r e Underdown I a e Mo W R 9°30’S on Pearce Cay Stephens I 9°30’S Deliverance I Pas Turnagain I sage Campbell I Nepean I Darnley I Emar Reef Dalrymple I Don Cay Kerr I Cay Aldai Reef s f Seo Reef e Cay ce n e Keats Islet a Numar Reef R tr n Marsden I E Nicholls Reef Yorke r rs o Big Mary e i d Sinclairs Rk Islands lin r Cay Reef F Beka Reef r Rennel I Massig Islet Kodall Islet Gabba I a W Smith Cay Kibi Meri Tudu I Reef Kai Mourilyan Reef Tagun Reef A Ba Kabbikane Islet Turu Cay E Reef silisk IN Gap Islet Pas U Hastings Zagai I sage Layoak Islet G Aukane Islet F W Gariar Reef Arden I E E N Reef Yam I Bourke Islet A IA Maer I E U L Anui Reef P A Dungeness R A R Aureed I Murray Is P T e Dowar I S Reef Mimi Islet ag U Mabuiag I Talab I s A as Wyer Islet Roberts Islet P R Passage I E 10°00’S Tancred Passage Dove Islet Gurigur 10°00’S North I nia I Watson Cay Sassie I Reef Passage er Coconut I ib R Newman -

THE STORY of CAPE YORK PENINSULA Torres Strait Saga

132 THE STORY OF CAPE YORK PENINSULA PART II Torres Strait Saga [By CLEM LACK, B.A., Dip.Jour.] (Read at a meeting of the Society on 28 February 1963.) In this second paper on Cape York Peninsula I propose to tell something of the history and folk lore of the Torres Strait Islanders, bringing the story of these remarkable island people up to the present day. They are in some respects one of the most outstanding coloured races to be found anywhere in the world. Anthro pologists and ethnologists hold divergent views on the racial origins of the Islanders; research upon their beginnings which is lost in the mists of Time has been largely neglected by scientific investigators, but the differing h3potheses are to some extent a reflection of the great controversy that has raged for many years, extending over almost a century, on the origins of the Polynesian race in general. VOYAGERS OUT OF THE SUNRISE The great Polynesian migration, or properly, migrations, extended over many centuries in the spread of this ancient race to every islet of the eastern Pacific. Fleets of brown- skinned voyagers came out of the sunrise and penetrated as far as the New Hebrides and New Zealand, and even to the coast of Peru, making voyages across thousands of leagues of ocean. Compared with these voyages the wanderings of Aeneas, and of Ulysses, and Jason's quest of the Golden Fleece would be the equivalent of a week-end hoUday cruise down to Moreton Bay. Some of them, I beUeve, stopped in the Straits waters, •among the archipelago of islets, some of them fertUe, others little more than sandy cays. -

Prescribed Bodies Corporate Directory April 2017

Prescribed Bodies Corporate April Directory 2017 Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (TSI) Corporation RNTBC [ICN: 4583]1 Preferred method of Chair The Badu Ar Mua Migi Lagal (Torres Strait Islanders) Corporation RNTBC communication: Maluwap Nona administers native title rights and interests on behalf of the people of Badu Email or phone call to Mr Ph: 0497643345 and Moa. Translated, the name means ‘Badu and Moa little islands’ and the Maluwap Nona and “cc: in John Email: determination area includes some 80 islands in the vicinity of Badu and Wigness [email protected] m Moa. Some of these islands are: Mailing Address: Parts of Matu (Whale Island) c/- TSIRC MER Deputy Chair Zurat (Phipps Island) MER, QLD, 4875 Saila Savage Kulbai (Spencer Island) Via Thursday Island QLD, 4875 Ph: 0400762194 Ngurtai (Quoin Island) Maitak (Wilson Island) Email: Treasurer chairperson.malulamar@gmail. Opeta James Kaitap Kanig (Duncan Island) com and Ph: 07 40694095 Ilapnab (Green Island) [email protected] Email: [email protected] Tukupai (Clarke Island) Ngul (Browne Island) Contact Person Tuin (Barney Island) John Wigness Ph: 07 4094833 Wia (High Island) Email: [email protected] Logan Rocks Gainaulai Directors: Tuft Rock Maluwap Nona Meth Islet Saila Savage Opeta James Kaitap Dadalai (Canoe Island) 1 Uninhabited Islands PBC; Inhabited Islands PBC; ICN= Indigenous Corporation Number ICN 1103 PBC Contact Information List ( Current as at 7 April 2017 ) Last Updated 7 April 2017 P a g e | 1 Prescribed Bodies Corporate April Directory