The City of Destiny's Darkest Hour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project

City of Tacoma Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project 1 Design Build Contract 2 City of Tacoma 3 Murray Morgan Bridge 4 Rehabilitation 5 6 Request for Proposal 7 September 28, 2010 8 9 10 11 12 13 Chapter 2: Technical 14 Requirements 15 16 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Technical Requirements September 28, 2010 City of Tacoma Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project 1 Contents 2 2.1 GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................... 2.1-1 3 2.1.1 GENERAL ...................................................................................................................... 2.1‐1 4 2.1.2 COMMUNICATIONS ..................................................................................................... 2.1‐6 5 2.1.3 PROJECT DOCUMENTATION ...................................................................................... 2.1‐10 6 2.1.4 SOFTWARE ................................................................................................................. 2.1‐14 7 2.2 MANDATORY STANDARDS ................................................................ 2.2-1 8 2.3 STATE TAXES ..................................................................................... 2.3-1 9 2.4 SURVEYS AND MAPPING ................................................................... 2.4-1 10 2.4.1 GENERAL ...................................................................................................................... 2.4‐1 11 2.4.2 MANDATORY STANDARDS .......................................................................................... -

Statement of Qualifications Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project

Submitted by: Kiewit Pacific Co. Statement of Qualifications Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project Specification No. PW10-0128F Submitted to: Purchasing Office, Tacoma Public Utilities 3628 South 35th Street, Tacoma, WA 98409 June 8, 2010 Tab No. 1 - General Company Information & Team Structure Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project Project TAB NO.1 - GENERAL COMPANY INFORMATION AND TEAM STRUCTURE Kiewit Pacific Co., a wholly-owned subsidiary of Kiewit Infrastructure Group, Inc., will be the contracting party for this project, as indicated on Forms 3 and 4 in Tab No. 4 - Appendix C. As a wholly-owned subsidiary, none of the officers of Kiewit Pacific Co. (Kiewit) own stock. Incorporated on May 18, 1982, we can trace our history back to 1884, when Peter and Andrew Kiewit formed Kiewit Brothers, an Omaha masonry contracting partnership. Today, we are part of one of North America's largest and most respected construction and mining organizations. We take our place in the corporate structure of our parent company, Kiewit Infrastructure Group Inc., alongside Kiewit Construction Company and Kiewit Southern Co. Our affiliates and subsidiaries, as well as those of our parent company, operate from a network of offices throughout North America. We draw upon the Kiewit Corporation’s collective experience and personnel to assemble the strongest team possible for a given project. Therefore, work experience of such affiliates and subsidiaries is relevant in demonstrating our capabilities. For the Murray Morgan Bridge, we are supplementing our local talent with extensive moveable bridge expertise from our east coast operations, Kiewit Constructors, Inc. We are also utilizing our local subsidiary, General Construction Company (General), for mechanical and electrical expertise. -

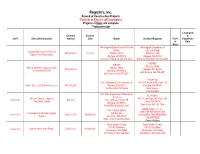

Projects *Projects in Red Are Still in Progress Projects in Black Are Complete **Subcontractor

Rognlin’s, Inc. Record of Construction Projects *Projects in Red are still in progress Projects in black are complete **Subcontractor % Complete Contract Contract & Job # Description/Location Amount Date Owner Architect/Engineer Class Completion of Date Work Washington Department of Fish and Washington Department of Wildlife Fish and Wildlife Log Jam Materials for East Fork $799,000.00 01/11/21 PO Box 43135 PO Box 43135 Satsop River Restoration Olympia, WA 98504 Olympia, WA 98504 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 WSDOT WSDOT PO Box 47360 SR 8 & SR 507 Thurston County PO Box 47360 $799,000.00 Olympia, WA 98504 Stormwater Retrofit Olympia, WA 98504 John Romero 360.570.6571 John Romero 360.570.6571 Parametrix City of Olympia 601 4th Avennue E. 1019 39th Avenue SE, Suite 100 Water Street Lift Station Generator $353,952.76 Olympia, WA 98501 Puyallup, WA 98374 Jim Rioux 360-507-6566 Kevin House 253.604.6600 WA State Department of Enterprise SCJ Alliance Services 14th Ave Tunnel – Improve 8730 Tallon Lane NE, Suite 200 20-80-167 $85,000 1500 Jefferson Street SE Pedestrian Safety Lacey, WA 98516 Olympia, WA 98501 Ross Jarvis 360-352-1465 Bob Willyerd 360.407.8497 ABAM Engineers, Inc. Port of Grays Harbor 33301 9th Ave S Suite 300 Terminals 3 & 4 Fender System PO Box 660 20-10-143 $395,118.79 12/08/2020 Federal Way, WA 98003-2600 Repair Aberdeen, WA 98520 (206) 357-5600 Mike Johnson 360.533.9528 Robert Wallace Grays Harbor County Grays Harbor County 100 W. -

King County King County Was Organized in 1852 from Lewis County

King County King County was organized in 1852 from Lewis County. It was originally named after William R. King, Vice President under Franklin Pierce; it was renamed, in 1986, after civil rights leader Martin Luther King. The first settlements in the county were the donation land claims of Luther Collins, Henry Van Asselt, and Jacob Maple in September of 1851 in the Duwamish Valley area of present day Seattle. This settlement was followed in November by one led by David Denny and Leander Terry at Alki Pont. The next year the Denny-Terry settlers moved to a better location for loading lumber on the east side of Elliott Bay and named the settlement Seattle after the friendly chief of the Duwamish Indians. The next year Henry Yesler set up the first steam sawmill on Puget Sound. King County and Seattle grew and prospered during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with the expansion of the shipping and lumber industries. It boomed again during and after World War II as an aircraft production and shipbuilding center. Today the county is the Pacific Northwest region’s major manufacturing and shipping center. Bounded by: Snohomish County (N), Chelan and Kittitas counties (E), Pierce County (S), and Puget Sound and Kitsap County (W). County Seat: Seattle Chambers of Commerce: Auburn Area Chamber of Commerce, 108 S Division #B, Auburn, WA, 98001-5305. Website: http://www.auburnareawa.org/ Phone 253-833-0700. Fax 253-735-4091. Ballard-Seattle Chamber of Commerce, 2208 NW Market St. #100, Ballard, WA 98107- 4030. Website www.ballardchamber.com Phone 206-784-9705, Fax 206-783-8154. -

Hard Drive to the Klondike: Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush

Hard Drive to the Klondike: Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush HARD DRIVE TO THE KLONDIKE: PROMOTING SEATTLE DURING THE GOLD RUSH A Historic Resource Study for the Seattle Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park Prepared for National Park Service Columbia Cascades Support Office Prepared by Table of Contents Lisa Mighetto Marcia Babcock Montgomery Historical Research Associates, Inc. Seattle, Washington November 1998 Last Updated: 18-Feb-2003 http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/klse/hrs.htm http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/klse/hrs/hrs.htm[1/23/2013 2:37:05 PM] Hard Drive to the Klondike: Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush (Table of Contents) HARD DRIVE TO THE KLONDIKE: PROMOTING SEATTLE DURING THE GOLD RUSH A Historic Resource Study for the Seattle Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION The Legacy of the Klondike Gold Rush CHAPTER ONE "By-and-By": The Early History of Seattle CHAPTER TWO Selling Seattle CHAPTER THREE Reaping the Profits of the Klondike Trade CHAPTER FOUR Building the City CHAPTER FIVE Interpreting the Klondike Gold Rush CHAPTER SIX Historic Resources in the Modern Era BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX (omitted from on-line edition) APPENDIX (omitted from on-line edition) U.S. Statute Creating the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park Local Firms Involved with the Klondike Gold Rush and Still in Business Locally Pioneer Square Historic District National Register Nomination (Established, 1970) Pioneer Square Historic District National Register Nomination (Boundary Extension, 1978) Pioneer Square Historic District National Register Nomination (Boundary Extension, 1987) First Avenue Groups National Register Nomination U.S. -

Fire and Gold Build Seattle Jeffery K

University of Washington Tacoma UW Tacoma Digital Commons History Undergraduate Theses History Spring 6-13-2014 Fire and Gold Build Seattle Jeffery K. Blair [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blair, Jeffery K., "Fire and Gold Build Seattle" (2014). History Undergraduate Theses. 5. https://digitalcommons.tacoma.uw.edu/history_theses/5 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UW Tacoma Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of UW Tacoma Digital Commons. Fire and Gold Build Seattle A Senior Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Undergraduate History Program of the University of Washington-Tacoma By Jeff Blair The University of Washington-Tacoma May 2014 Thesis Advisor: Dr. Mike Allen, History and American Studies 1 Abstract The final decade of the 19 th century established Seattle as the preeminent city in the Pacific Northwest. Prodigious changes resulting from the Fire of 1889 paved the way for Seattle to take full advantage of the Klondike Gold Rush eight years later. This work details the impact that each of these events had on Seattle and concludes that the compound effects of two events of happenstance created the foundation for the Seattle we know today. 2 Introduction Seattle was founded in of 1852. The area showed great promise. It sat at the edge of a deep-water sheltered bay that was ideal for shipping. The pine and cypress forest that surrounded the settlement promised a strong future in timber, and the waters of Puget Sound were a rich fishery. -

United States

United States US Senator Education: Warren received a Navy scholarship to and graduated from Oregon State University in Chemical Engineering. Before college he was a national guards- man and after graduation served eighteen years as a commissioned naval officer and received training in nuclear - biological - chemical defense and deep sea diving. Occupation: Warren commercially fished for salmon in Washington and Alaska for forty plus years and currently is working as a casual longshoreman at the Tacoma and Seattle ports. Professional Qualifications: Warren’s military service, mental and physical strengths, life experiences, hard work. Plus willingness to accept difficult tasks qualifies him to meet the challenges of this office. Personal Information: Warren is a single man of excellent health with an active Warren E. Hanson mind, spirit and body. He is the father of three healthy daughters with two excellent Democratic sons-in-laws, three grandchildren and one additional young lady, a mother of four, PMB 444 who is like a fourth daughter. 4320 196th St SW Community Involvement: Warren has served in many church capacities, as a Red Cross Board Member and is a frequent blood donor. Lynnwood, WA 98036 Personal Views: Warren will work forcefully to secure our boarders, to drastically (425) 418-2736 reduce illegals, to be more selective in legal entries and to solve the many problems that interfere with a good life for all citizen Americans. Education: Occupation: Professional Qualifications: Personal Information: Community Involvement: Personal Views: Washington state is a great place to live and raise a family. We must preserve and build on the things that make us strong. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Puget's Sound a Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound by Murray Morgan Puget's Sound

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Puget's Sound A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound by Murray Morgan Puget's Sound. El lector de libros de texto electrónicos número uno del mundo para estudiantes. VitalSource es el principal proveedor de libros de texto y materiales didácticos en línea. Más de 15 millones de usuarios han utilizado nuestra plataforma Bookshelf durante el último año para mejorar su experiencia de aprendizaje y sus resultados. Con el acceso en cualquier momento y en cualquier lugar y las diferentes herramientas integradas, tales como resaltadores, fichas y grupos de estudio, es fácil entender por qué tantos estudiantes se están digitalizando con Bookshelf. Más de un millón. de títulos disponibles de más de 1.000 editores. reseñas de los clientes con una calificación promedio de 9,5. Más de 3 mil millones. de páginas digitales vistas en los últimos 12 meses. instituciones que utilizan Bookshelf en 241 países. Puget's Sound A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound por Murray Morgan y Editor University of Washington Press. Ahorra hasta un 80% al elegir la opción de libro de texto electrónico para el ISBN: 9780295744629, 0295744626. La versión impresa de este libro de texto es el ISBN: 9780295744230, 0295744235. Puget's Sound A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound por Murray Morgan y Editor University of Washington Press. Ahorra hasta un 80% al elegir la opción de libro de texto electrónico para el ISBN: 9780295744629, 0295744626. La versión impresa de este libro de texto es el ISBN: 9780295744230, 0295744235. Puget's Sound. -

The Open Door (PDF)

The Open Door: A History of Tacoma Community College By Dale Coleman 2 Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................... 4 Foreword .......................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: A Community College in Tacoma ........................ 7 Chapter 2: The Opening Door ................................................... 17 Chapter 3: Independence ........................................................... 38 Chapter 4: The Times They Are a-Changin' ......................... 46 Chapter 5: Strike! .......................................................................... 68 Chapter 6: The Test of Time ..................................................... 77 Chapter 7: Management by Walking Around ................... 101 Chapter 8: Focus on the Future ............................................. 115 Chapter 9: A Reflection of Quality ........................................ 128 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the members of the TCC History Advisory Board. This project would not have been possible without your guidance and support. To Allen Braden, Frank Garratt, Ron Magden, Georgia McDade, Dan Small, Richard Wakefield, Sharon Winters, Chris Young and Ed Zimmerman – thank you for all you continue to do in support of Tacoma Community College. I would also like to thank to Shawn Jennison and Rachel Payne for their timely advice and feedback, Elizabeth Russell for allowing me to run riot, for over a year, in her beloved College Archive, -

Wash Trust News3.Qxd

NewsTRUST ISSUE 1 G 2009 New National Register District— Wenatchee Downtown By Kris Bassett, City of Wenatchee Historic Since that time, 26 individual commercial downtown Preservation Officer properties have been listed on the Wenatchee Register of Historic Places.With the opportunity for CLG grant funding to fully support a re-survey of the downtown properties, the option to form a district was again introduced to the property owners. The next step in the process was writing the National Register nomination and identifying a potential dis- trict. The survey/inventory and nomination process was conducted with the assistance of Eugenia Woo, Artifacts Consulting, who over 2 years, compiled all the necessary documentation for the nomination. In This Issue DOWNTOWN WENATCHEE NOW HAS THE HONOR OF BEING DESIGNATED BY THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE In the late summer of 2008, crews finished the reno- G LAKE UNION PAST AND AS A NATIONAL REGISTER DISTRICT! The boundary vation of the last two remaining full-brick streets in PRESENT will include 87 properties in an eight-block area the city, downtown on Orondo Avenue and Palouse located between Mission and Columbia streets from Street, preserving further history.Thanks to the G HISTORIC MOCLIPS First to Kittitas. Buildings dating back to 1894 (the Department of Transportation Enhancement Fund CABOOSE IS RESTORED Morris Building on Wenatchee Avenue) illustrate a and the City of Wenatchee, both roads were restored range of architectural styles, including Art Deco, and previous patches of concrete removed. New G FOURTH ANNUAL Beaux Arts, Georgian Revival, Federal and crosswalks were poured at the Mission Street inter- LANDMARK DEEDS AWARDS Craftsman. -

The Trail, 1951-11-16

Pt- r! I) r STAFF EDITOR - DOROTHY ROSS BUSINESS MANAGER -------------------------TOMMY MEADOWCROFT Photographers------------------------------------Bob Rudsit, Roy Nickson Cartoonist------------------------------------------------------John Clark Adviser----------------------------------------------------Murray Morgan Staff--------------Doug McArthur, Don Lewis, Joe Contris, Jack Gallaher, Cal Halbert, Bob Daniel, Pat Smyth, Patt Thompson, Richard Dunn, Jeanne Marie Henroit, Suzanne Bervin, Jo Copple, Doug Cullen, Adele Houx, Steve Tudor. Once upon a time, there were 14,000 rabbits - as you can well imagine 28,000 rabbits are quite a few - but the funny thing about these 56,000 rab- bits is that they did not care where they WERE. Now you might think this a little strange because any normal person would be quite willing to be THERE rather than being just WERE 112,000 rabbits were not really concerned about the where- abouts of WERE, because they were too busy being rabbits. Not everybody can be as busy as 224,000 rabbits, so naturally they care about where they I" ARE. Therefore it's quite nat- ural that you should go to I.1 1 , CHARLESONS "Professor Lubnug is still working for peanuts!" J4 — 1M.LMIILIIIrnJ 4 e€ eed Stade.t4 eô&,e o et Sd College of Pugef Sound NOVEMBER 16, 1951 Tacoma, Washington CAMPUS WEEK A strong wind blew an icy draft over the campus Monday. A Sigma Chi work party came back from Chinook, felt the cold atmosphere, and almost went back (See Stu- dents). The football club received con- grats on their seasonal record, and Coach John beamed as he praised their fine team Spirit (See Sports). He traded his cleated shoes for softer ones as basketball season and the first game November 26th drew closer. -

Promoting Seattle During the Gold Rush. a Historic Resource Study for the Seattle Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 437 334 SO 031 419 AUTHOR Mighetto, Lisa; Montgomery, Marcia Babcock TITLE Hard Drive to the Klondike: Promoting Seattle during the Gold Rush. A Historic Resource Study for the Seattle Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. SPONS AGENCY National Park Service (Dept. of Interior), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-11-00 NOTE 407p. AVAILABLE FROM National Park Service, Columbia Cascades Support Office, Attn: Cultural Resources, 909 First Avenue, Seattle, WA 98104-1060. For full text: <http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/k1se/hrstoc.htm>. PUB TYPE Historical Materials (060) Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Built Environment; *Cultural Context; Heritage Education; History Instruction; Local History; *Municipalities; Secondary Education; *Social History; Social Studies; *United States History IDENTIFIERS Alaska; Historical Research; National Register of Historic Places; Urban Development; *Washington (Seattle) ABSTRACT The Alaskan Klondike Gold Rush coincided with major events, including the arrival of the railroad, and it exemplified continuing trends in Seattle's (Washington) history. If not the primary cause of the city's growth and prosperity, the Klondike Gold Rush nonetheless serves as a colorful reflection of the era and its themes, including the celebrated "Seattle spirit." This historic resource study examines the Klondike Gold Rush, beginning in the early 1850's with the founding of Seattle, and ending in 1909 with the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition commemorating the Klondike Gold Rush and the growth of the city. Chapter 1 describes early Seattle and the gold strikes in the Klondike, while the following three chapters analyze (how the city became the gateway to the Yukon, how the stampede to theFar 'North stimulated local businesses, and how the city's infrastructure and boundaries changed during the era of the gold rush.