Map 38 Cyrene Compiled by D.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, 15 JANUARY, 1948 Hardest Part of the Business, As It Is Likely to 2

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 15 JANUARY, 1948 hardest part of the business, as it is likely to 2. The enemy, however, may try to drive us entail stationing the bulk, if not the whole, of back from our present positions round Gazala our armoured force south of the Gebel Akhdar and from Tobruk, before we are ready to area to guard against any enemy attempt to launch our offensive. move north against the garrison of Bengasi, which itself must be strictly limited in size by 3. It is essential to retain Tobruk as a supply maintenance considerations. The operation base for our offensive. Our present positions should not be impossible, however, .though it on the line Gazala—Hacheim will, therefore, will be more difficult than in December last, continue to be held, and no effort will be as we shall not have a beaten and disorganized spared to make them as strong as possible. enemy to deal with as we had then. The impli- 4. If, for any reason, we should be forced at cation of this is that the operation is likely to some future date to withdraw from our present have to be much more deliberate. forward positions, every effort will still be made 10. Our immediate need therefore is to to prevent Tobruk -being lost to the enemy; but stabilise a front in Libya behind which we can it is not my intention to' continue to hold it build up a striking force with which to resume once the enemy is in a position to invest it effectively. -

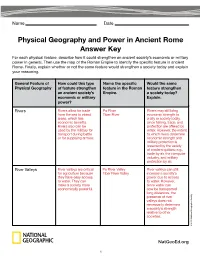

Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer

Name Date Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key For each physical feature, describe how it could strengthen an ancient society’s economic or military power in general. Then use the map of the Roman Empire to identify the specific feature in ancient Rome. Finally, explain whether or not the same feature would strengthen a society today and explain your reasoning. General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. a society today? economic or military Explain. power? Rivers Rivers allow for trade Po River Rivers may still bring from the sea to inland Tiber River economic strength to areas, which has a city or society today, economic benefits. since fishing, trade, and Rivers also can be protection are offered by used by the military for water. However, the extent transport during battle to which rivers determine or for supplying armies. economic strength and military protection is lessened by the variety of modern options: e.g., trade by air, the computer industry, and military protection by air. River Valleys River valleys are critical Po River Valley River valleys can still for agriculture because Tiber River Valley increase a society’s they have easy access power due to access to water. They can to water. However, make a society more since water can economically powerful. now be transported long distances, the presence of river valleys does not necessarily determine a society’s strength relative to other societies. © 2015 National Geographic Society NatGeoEd.org 1 Physical Geography and Power in Ancient Rome Answer Key, continued General Feature of How could this type Name the specific Would the same Physical Geography of feature strengthen feature in the Roman feature strengthen an ancient society’s Empire. -

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of SE Asia ©2012, TESCCC World Geography Unit 12, Lesson 01 Archipelago • A group of islands. Cordilleras • Parallel mountain ranges and plateaus, that extend into the Indochina Peninsula. Living on the Mainland • Mainland countries include Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos • Laos is a landlocked country • The landscape is characterized by mountains, rivers, river deltas, and plains • The climate includes tropical and mild • The monsoon creates a dry and rainy season ©2012, TESCCC Identify the mainland countries on your map. LAOS VIETNAM MYANMAR THAILAND CAMBODIA Human Settlement on the Mainland • People rely on the rivers that begin in the mountains as a source of water for drinking, transportation, and irrigation • Many people live in small villages • The river deltas create dense population centers • River create rich deposits of sediment that settle along central plains ©2012, TESCCC Major Cities on the Mainland • Myanmar- Yangon (Rangoon), Mandalay • Thailand- Bangkok • Vietnam- Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) • Cambodia- Phnom Penh ©2012, TESCCC Label the major cities on your map BANGKOK YANGON HO CHI MINH CITY PHNOM PEHN Chao Phraya River • Flows into the Gulf of Thailand, Bangkok is located along the river’s delta Irrawaddy River • Located in Myanmar, Rangoon located along the river Mekong River • Longest river in the region, forms part of the borders of Myanmar, Laos, and Thailand, empties into the South China Sea in Vietnam Label the important rivers and the bodies of water on your map. MEKONG IRRAWADDY CHAO PRAYA ©2012, TESCCC Living on the Islands • The island nations are fragmented • Nations are on islands are made up of island groups. -

Callovian and Tithonian Paleogeography Legend (.Pdf)

CALLOVIAN AND TITHONIAN AaTa Aaiun-Tarfay a Basin EVB East Venezuela Basin Mar Mardin SBet Subbetic Adha Adhami Ev ia Ev ia MarB Marmarica Basin SuBu Subbucov inian PALEOGEOGRAPHY Adri Adriatic Ex Li Ex ternal Ligurian Mars Marseille SuDa Susuz Dag LEGEND Akse Akseki Ex Ri Ex ternal Rif MAt Middle Atlas SuGe Supra-Getic Alda Aldama Ex Su Ex ternal Subetic MaU May a Uplift SuMo Supramonte Almo Almopias Ex u Ex uma MazP Mazagan Plateau Tab Tabriz Author: Caroline Wilhem Ana Anamas Fat Fatric Mec Mecsek Taba Tabas University of Lausanne - Institute of Earth Sciences Ani Anina FCB Flemish Cap Basin MC Massif Central Tac Tacchi Sheet 3 (3 sheets: 2 maps + legend; explanatory text) Ann Annecy Flor Florida Med Medv elica TadB Taoudeni Basin Anta Antaly a FoAm Foz do Amazonas Basin Mel Meliata Tahu Tahue Apu Apulia Fran Francardo Men Menderes Tal Talesh Aqui Aquitaine Basin Fri Friuli Meri Merida TaMi Tampica-Misant Basina Argo Argolis Gab Gabrov o Mese Meseta TanA Tanaulipas Arch PALEOENVIRONMENTS Armo Armorica GalB Galicia Bank MeSu Median Subbetic TaOr Talea Ori Ask Askipion Gav Gav roro Mig Migdhalista Tat Tatric Exposed land Atla Atlas GBB Grand Banks Basin Mir Mirdita Teh Tehran GeBB Georges Bank Basin Fluviodeltaic environment BaCa Baja California Mist Mistah Terek Terek BaDa Barla Dag GCau Great Caucasus Mix Mix teca TeT Tellian Trough Evaporitic platform Bade Badenli Geme Gemeric Mo Mostar Theo Theokafta Baju Bajuv aric Gen Genev a MoeP Moesian Platform TimB Timimoun Basin Terrigenous shelf and shallow basin Bako Bakony Gere Gerecse Monc -

Landscapes of NE-Africa and W-Asia—Landscape Archaeology As a Tool for Socio-Economic History in Arid Landscapes

land Article ‘Un-Central’ Landscapes of NE-Africa and W-Asia—Landscape Archaeology as a Tool for Socio-Economic History in Arid Landscapes Anna-Katharina Rieger Institute of Ancient History and Classical Antiquities, University of Graz, A-8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected]; Tel.: +43-316-380-2391 Received: 6 November 2018; Accepted: 17 December 2018; Published: 22 December 2018 Abstract: Arid regions in the Old World Dry Belt are assumed to be marginal regions, not only in ecological terms, but also economically and socially. Such views in geography, archaeology, and sociology are—despite the real limits of living in arid landscapes—partly influenced by derivates of Central Place Theory as developed for European medieval city-based economies. For other historical time periods and regions, this narrative inhibited socio-economic research with data-based and non-biased approaches. This paper aims, in two arid Graeco-Roman landscapes, to show how far approaches from landscape archaeology and social network analysis combined with the “small world phenomenon” can help to overcome a dichotomic view on core places and their areas, and understand settlement patterns and economic practices in a nuanced way. With Hauran in Southern Syria and Marmarica in NW-Egypt, I revise the concept of marginality, and look for qualitatively and spatially defined relationships between settlements, for both resource management and social organization. This ‘un-central’ perspective on arid landscapes provides insights on how arid regions functioned economically and socially due to a particular spatial concept and connection with their (scarce) resources, mainly water. Keywords: aridity; marginality; landscape archaeology; Marmarica (NW-Egypt); Hauran (Syria/ Jordan); Graeco-Roman period; spatial scales in networks; network relationship qualities; interaction; resource management 1. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

Theon of Alexandria and Hypatia

CREATIVE MATH. 12 (2003), 111 - 115 Theon of Alexandria and Hypatia Michael Lambrou Abstract. In this paper we present the story of the most famous ancient female math- ematician, Hypatia, and her father Theon of Alexandria. The mathematician and philosopher Hypatia flourished in Alexandria from the second part of the 4th century until her violent death incurred by a mob in 415. She was the daughter of Theon of Alexandria, a math- ematician and astronomer, who flourished in Alexandria during the second part of the fourth century. Information on Theon’s life is only brief, coming mainly from a note in the Suda (Suida’s Lexicon, written about 1000 AD) stating that he lived in Alexandria in the times of Theodosius I (who reigned AD 379-395) and taught at the Museum. He is, in fact, the Museum’s last attested member. Descriptions of two eclipses he observed in Alexandria included in his commentary to Ptolemy’s Mathematical Syntaxis (Almagest) and elsewhere have been dated as the eclipses that occurred in AD 364, which is consistent with Suda. Although originality in Theon’s works cannot be claimed, he was certainly immensely influential in the preservation, dissemination and editing of clas- sic texts of previous generations. Indeed, with the exception of Vaticanus Graecus 190 all surviving Greek manuscripts of Euclid’s Elements stem from Theon’s edition. A comparison to Vaticanus Graecus 190 reveals that Theon did not actually change the mathematical content of the Elements except in minor points, but rather re-wrote it in Koini and in a form more suitable for the students he taught (some manuscripts refer to Theon’s sinousiai). -

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya BBQPERTY OF U.S.GW«r..GlCAL SURVEY JRENTON, NEW JEST.W Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya By W. W. DOYEL and F. J. MAGUIRE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract _ _______________-__--__-_______--__--_-__---_-------_--- Bl Introduction______-______--__-_-____________--------_-----------__ 1 Location and extent of area-----_______----___--_-------------_- 1 Purpose and scope of investigation---______-_______--__-------__- 3 Acknowledgments __________________________-__--_-----_--_____ 3 Geography___________--_---___-_____---____------------_-___---_- 5 General features.._-_____-___________-_-_____--_-_---------_-_- 5 Topography and drainage_______________________--_-------.-_- 6 Climate.____________________.__----- - 6 Geology____________________-________________________-___----__-__ 8 Ground water____._____________-____-_-______-__-______-_--_--__ 10 Bengasi municipal supply_____________________________________ 12 Other water supplies___________________-______-_-_-___-_--____- 14 Test drilling....______._______._______.___________ 15 Conclusions. -

The Annual of the British School at Athens A

The Annual of the British School at Athens http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH Additional services for The Annual of the British School at Athens: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here A Visit to Cyrene in 1895 Herbert Weld-Blundell The Annual of the British School at Athens / Volume 2 / November 1896, pp 113 - 140 DOI: 10.1017/S0068245400007115, Published online: 18 October 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068245400007115 How to cite this article: Herbert Weld-Blundell (1896). A Visit to Cyrene in 1895. The Annual of the British School at Athens, 2, pp 113-140 doi:10.1017/S0068245400007115 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ATH, IP address: 131.173.48.20 on 15 Apr 2015 ' itfS i^>- tv lli-JOTb. V**»-iJ IhUS ntt < POINTS'Si/HEHCEl PHOTMOHAPMS ARE British School at Athens, Annual II. PLATE IV. RUINS OF CYRENE: GENERAL PLAN. A VISIT TO CYRENE IN 1895. A VISIT TO CYRENE IN 1895. BY HERBERT WELD-BLUNDELL. PLATE IV. THE difficulties that hedged round the Garden of the Hes- perides in the Greek seem still destined to make the Cyrenaica, a country to which the eyes of archaeologists have so wistfully turned, almost as inaccessible to the modern traveller as to the heroes of ancient fable. The classic maidens have vanished, the Garden is some- what run to seed, but the dragon of early legend is there, in the person of the native official who guards the historical treasures that lie strewn over the rich sites of the Pentapolis, stately tombs that worthless Arabs kennel in or plunder for statues and vases, to be peddled to Maltese or Greeks for (literally) home consumption or foreign export. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Roman Life in Cyrenaica in the Fourth Century As Shown in the Letters of Synesius, Bishop of Ptolemais

920 T3ee H. C. Thory Roman Life in Cyrenaica in the Fourth Century as Shown in the Letters of 5y nesius, , Si shop of Ptolernais ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY AS SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PTOLEMAIS BY t HANS CHRISTIAN THORY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS IN CLASSICS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1920 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 7 20 , 19* THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Chrifti^„.T^ i2[ H^.s.v t : , , ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY ENE Af*111rvi'T TLEDT?rt A? SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PTQLEMAIS IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF ^3 Instructor in Charge Approved HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF ,£M?STCS. CONTENTS Page I. Cyrenaica: the Country and its Hiatory 1 II. The Barbarian Invasions.. 5 III. Government: Military and Civil 8 IV. The Church 35 V. Organization of Society 34 VI. Agriculture Country Life 37 vii, Glimpses of City Life the Cities 46 VIII. Commerce Travel — Communication 48 IX. Language — • Education Literature Philosophy Science Art 57 X. Position of Women Types of Men 68 Bibliography 71 ********** 1 ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY AS SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PT0LEMAI8 I CYRENAICA: THE COUNTRY AND ITS HISTORY The Roman province of Cyrenaioa occupied the region now called Barca, in the northeastern part of Tripoli, extending eaet from the Greater Syrtis a distance of about 20C miles, and south from the Mediterranean Sea a distance of 70 to 80 miles. -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment