The Annual of the British School at Athens A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Roman Life in Cyrenaica in the Fourth Century As Shown in the Letters of Synesius, Bishop of Ptolemais

920 T3ee H. C. Thory Roman Life in Cyrenaica in the Fourth Century as Shown in the Letters of 5y nesius, , Si shop of Ptolernais ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY AS SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PTOLEMAIS BY t HANS CHRISTIAN THORY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS IN CLASSICS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1920 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS June 7 20 , 19* THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Chrifti^„.T^ i2[ H^.s.v t : , , ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY ENE Af*111rvi'T TLEDT?rt A? SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PTQLEMAIS IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF ^3 Instructor in Charge Approved HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF ,£M?STCS. CONTENTS Page I. Cyrenaica: the Country and its Hiatory 1 II. The Barbarian Invasions.. 5 III. Government: Military and Civil 8 IV. The Church 35 V. Organization of Society 34 VI. Agriculture Country Life 37 vii, Glimpses of City Life the Cities 46 VIII. Commerce Travel — Communication 48 IX. Language — • Education Literature Philosophy Science Art 57 X. Position of Women Types of Men 68 Bibliography 71 ********** 1 ROMAN LIFE IN CYRENAICA IN THE FOURTH CENTURY AS SHOWN IN THE LETTERS OF SYNESIUS, BISHOP OF PT0LEMAI8 I CYRENAICA: THE COUNTRY AND ITS HISTORY The Roman province of Cyrenaioa occupied the region now called Barca, in the northeastern part of Tripoli, extending eaet from the Greater Syrtis a distance of about 20C miles, and south from the Mediterranean Sea a distance of 70 to 80 miles. -

HESPERIDES and HEROES: a NOTE on the THREE-FIGURE RELIEFS 77 Knife, That This Is a Moment of Dark Foreboding

HESPERIDESAND HEROES: A NOTE ON THE THREE-FIGURERELIEFS (PLATES 11-14) flflHOUGH not a scrap of the original reliefs has been found, Thompson's attri- bution to the Altar of the Twelve Gods of the four famous three-figure reliefs known to us from Roman copies is one of the more important results of the Agora excavations for the history of Athenian sculpture in the late 5th century.1 The dating and interpretation of these reliefs is also vitally related to the history of other monu- ments of the Agora. I should like, therefore, to suggest a modification of Thompson's views on these points. Before Thompson's discovery that the dimensions of the reliefs admirably filled the spaces flanking the east and west entrances in the parapet surrounding the altar (P1. 12, b), the originals had generally been attributed to a choregic monument. This was because two of the reliefs, the Orpheus and Peliad reliefs (P1. 12, d, e), are notably tragic in their impact, including the elements of irony and reversal of fortune which we commonly associate with Attic tragedy. The two others, Herakles, Theseus and Peirithoos in the underworld (P1. 12, a, c) and Herakles in the Garden of the Hesperides (P1. 11, a-d), could also well be drawn from the subjects of tragedies performed in Athens.2 In order to interpret the last two in the same spirit as the first two, however, it was necessary to resort to the subtle language of literary interpretation rather than to the simpler language of art. No one could doubt, on looking at the Peliad with the " ' The Altar of Pity in the Athenian Agora," Hesperia, XXI, 1952, pp. -

The Religion of Ancient Palestine in the Light of Archaeology the God of Beth-Shan the Religion of Ancient Palestine in the Light of Archaeology

THE SCHWEICH LECTURES ON BIBLICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, 1925 THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT PALESTINE IN THE LIGHT OF ARCHAEOLOGY THE GOD OF BETH-SHAN THE RELIGION OF ANCIENT PALESTINE IN THE LIGHT OF ARCHAEOLOGY BY STANLEY A. COOK, M.A., LITT.D. FELLOW OF GONVILLE AND CAIUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LECTURER IN HEBREW AND ARAMAIC THE SCHWEICH LECTURES OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY LONDON PUBLISHED FOR THE BRITISH ACADEMY BY HUMPHREY MILFORD, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E,C. 1930 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AMEN HOUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW LEIPZIG NEW YOR~ TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPETOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY Printed in Great Britain PREFACE HE title and subject of this book will recall the in T auguration of the Schweich Lectures more than twenty years ago, when the late Samuel Rolles Driver gave an account of the contribution of archaeology and the monu ments to Biblical study. Modern Research as illustrating the Bible, the title of his lectures, was a subject to which that great and many-sided scholar felt himself closely drawn; and neither that book nor any of his other writings on the subject can be ignored to-day in spite of the time that has elapsed. For although much has been done, especially since the War, in adding to our knowledge of Oriental archaeo logy and in the discussion of problems arising therefrom, Dr. Driver performed lasting service, not only in opening up what to many readers was a new world, but also in setting forth, with his usual completeness and clearness, both the real significance of the new discoveries and the principles to be employed when the Biblical records and the 'external' evidence are inter-related.1 When, therefore, I was asked, in 1925, to deliver the Schweich Lectures, the suggestion that some account might be given of the work subsequent to 1908 encouraged the wish I had long entertained: to reconsider the religion of Palestine primarily and mainly from the point of view of archaeology. -

With Archaeologist Kathleen Lynch

THE LEGACY OF Ancient Greece October 13-25, 2021 (13 days | 16 guests) with archaeologist Kathleen Lynch Delphi © Runner1928 Archaeology-focused tours for the curious to the connoisseur Archaeological Institute of America xperience the glories of Greece, from the Bronze Age to the Classical era and beyond, amid the variety of springtime landscapes of the mainland Lecturer & Host and the Peloponnese peninsula. This is a superb opportunity to ignite, Kathleen Lynch Eor reignite, your passion for the wonders of Greek archaeology, art, and ancient is Professor history and to witness how integral mythology, religion, drama, and literature of Classics at the University are to their understanding. This well-paced tour, from city to mountains to of Cincinnati seaside, spends a total of four nights in the modern yet historic capital, Athens; and a classical two nights in the charming port town of Nafplion; one night in Dimitsana, archaeologist with a medieval mountain village; two nights in Olympia, home of the original a focus on ancient Olympic Games; and two nights in the mountain resort town of Arachova, Greek ceramics. She earned her near Delphi. Ph.D. from the Highlights include: University of Virginia, and has worked on archaeological projects at sites in • SIX UNESCO World Heritage Sites: Greece (Athenian Agora, Olynthos, ˚ Athens’ Acropolis, with its stunning Parthenon and Erechtheion Corinth, Pylos), Turkey (Gordion, temples, plus the nearby Acropolis Museum; Troy), Italy (Morgantina), and Albania (Apollonia). Kathleen’s research considers ˚ the greatest ancient oracle, Delphi, located in a spectacular what ancient ceramics can tell us mountain setting; about their use and users. -

The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers

OriginalverCORE öffentlichung in: A. Erskine (ed.), A Companion to the Hellenistic World,Metadata, Oxford: Blackwell citation 2003, and similar papers at core.ac.uk ProvidedS. 431-445 by Propylaeum-DOK CHAPTKR TWENTY-FIVE The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers Anßdos Chaniotis 1 Introduction: the Paradox of Mortal Divinity When King Demetrios Poliorketes returned to Athens from Kerkyra in 291, the Athenians welcomed him with a processional song, the text of which has long been recognized as one of the most interesting sources for Hellenistic ruler cult: How the greatest and dearest of the gods have come to the city! For the hour has brought together Demeter and Demetrios; she comes to celebrate the solemn mysteries of the Kore, while he is here füll of joy, as befits the god, fair and laughing. His appearance is majestic, his friends all around him and he in their midst, as though they were stars and he the sun. Hail son of the most powerful god Poseidon and Aphrodite. (Douris FGrH76 Fl3, cf. Demochares FGrH75 F2, both at Athen. 6.253b-f; trans. as Austin 35) Had only the first lines of this ritual song survived, the modern reader would notice the assimilaüon of the adventus of a mortal king with that of a divinity, the etymo- logical association of his name with that of Demeter, the parentage of mighty gods, and the external features of a divine ruler (joy, beauty, majesty). Very often scholars reach their conclusions about aspects of ancient mentality on the basis of a fragment; and very often - unavoidably - they conceive only a fragment of reality. -

In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia

Advance press kit Exhibition From October 13, 2011 to January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Ancient Macedonia Contents Press release page 3 Map of main sites page 9 Exhibition walk-through page 10 Images available for the press page 12 Press release In the Kingdom of Alexander the Great Exhibition Ancient Macedonia October 13, 2011–January 16, 2012 Napoleon Hall This exhibition curated by a Greek and French team of specialists brings together five hundred works tracing the history of ancient Macedonia from the fifteenth century B.C. up to the Roman Empire. Visitors are invited to explore the rich artistic heritage of northern Greece, many of whose treasures are still little known to the general public, due to the relatively recent nature of archaeological discoveries in this area. It was not until 1977, when several royal sepulchral monuments were unearthed at Vergina, among them the unopened tomb of Philip II, Alexander the Great’s father, that the full archaeological potential of this region was realized. Further excavations at this prestigious site, now identified with Aegae, the first capital of ancient Macedonia, resulted in a number of other important discoveries, including a puzzling burial site revealed in 2008, which will in all likelihood entail revisions in our knowledge of ancient history. With shrewd political skill, ancient Macedonia’s rulers, of whom Alexander the Great remains the best known, orchestrated the rise of Macedon from a small kingdom into one which came to dominate the entire Hellenic world, before defeating the Persian Empire and conquering lands as far away as India. -

The Coinage of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium 31 3.1 Introduction 31 3.2 Brief Discussion of the Coin Types 31

Ross, Scott (2013) An assessment and up-to-date catalogue of the coins of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium between the 5th and 1st centuries B.C. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4335/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Scott Ross MA (Hons) 0706244 “An assessment and up-to-date catalogue of the coins of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium between the 5th and 1st centuries B.C.” Submitted for the honour of Master of Philosophy (by research) 2012 Classics, School of Humanities, University of Glasgow 1 Acknowledgments 3 Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Methodology 7 Chapter 2: The History of Illyria 12 2.1 Introduction 12 2.2 Physical geography 13 2.3 Political structure of Illyria 15 2.4 Conflict and turmoil 17 2.5 Piracy and Roman intervention 20 2.6 Conclusions 29 Chapter 3: The Coinage of Apollonia and Dyrrhachium 31 3.1 Introduction 31 3.2 Brief discussion of the coin types 31 Chapter 4: Weight standard and circulation 35 Chapter 5: Iconography of Silver Issues 41 5.1 Corcyrean Staters 41 5.2 Corinthian Staters 44 5.3 Drachms 45 5.4 Apollo Denarius 48 5.5 Conclusions 49 Chapter 6: Conclusion 50 Catalogue 52 Monograms 236 Bibliography 238 List of Images 241 2 Acknowledgements This is to say thanks to: Dr. -

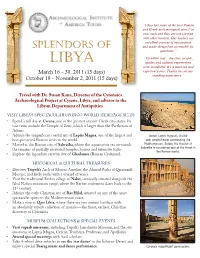

Splendors of and Made Themselves Accessible for Questions.”

“Libya has some of the best Roman and Greek archaeological sites I’ve ever seen and they are not overrun with other tourists. Our leaders are excellent sources of information SplendorS of and made themselves accessible for questions.” “Excellent tour—the sites, people, libya guides and cultural experiences were wonderful. It’s a must see and March 16 – 30, 2011 (15 days) experience tour. Thanks for an out- October 19 – November 2, 2011 (15 days) standing experience.” Travel with Dr. Susan Kane, Director of the Cyrenaica Archaeological Project at Cyrene, Libya, and advisor to the Libyan Department of Antiquities. VISIT LIBYA’S SPECTACULAR UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITES: • Spend a full day at Cyrene, one of the greatest ancient Greek city-states. Its vast ruins include the Temple of Zeus, which is larger than the Parthenon of Athens. • Admire the magnificent coastal site of Leptis Magna, one of the largest and Above, Leptis Magna’s 16,000 seat amphitheater overlooking the best-preserved Roman cities in the world. Mediterranean. Below, the theater at • Marvel at the Roman city of Sabratha, where the aquamarine sea surrounds Sabratha is considered one of the finest in the remains of partially excavated temples, houses and extensive baths. the Roman world. • Explore the legendary caravan city of Ghadames (Roman Cydamus). HISTORICAL & CULTURAL TREASURES • Discover Tripoli’s Arch of Marcus Aurelius, the Ahmad Pasha al Qaramanli Mosque, and lively souks with a myriad of wares. • Visit the traditional Berber village of Nalut, scenically situated alongside the Jabal Nafusa mountain range, where the Berber settlement dates back to the 11th century. -

The Classical Mythology of Milton's English Poems

YALE STUDIES IN ENGLISH ALBERT S. COOK, Editor VIII THE CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY OF Milton's English poems CHARLES GROSVENOR OSGOOD, Ph.D. NEW YORK HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY igoo Ss9a Copyright, igoo, BY CHARLES GROSVENOR OSGOOD, Ph.D. J^ 7/SS TO PROFESSQR ALBERT S. COOK AND PROFESSOR THOMAS D. SEYMOUR — PREFACE The student who diligently peruses the lines of a great poem may go far toward a realization of its char- acter. He may appreciate, in a degree, its loveliness, strength, and direct hold upon the catholic truth of life. But he will be more sensitive to these appeals, and receive gifts that are richer and less perishable, accord- ing as he comprehends the forces by whose interaction the poem was produced. These are of two kinds the innate forces of the poet's character, and certain more external forces, such as, in the case of Milton, are represented by Hellenism and Hebraism. Their activ- ity is greatest where they meet and touch, and at this point their nature and measure are most easily dis- cerned. From a contemplation of the poem in its gene- sis one returns to a deeper understanding and enjoyment of it as a completed whole. The present study, though it deals with but one of the important cultural influ- ences affecting Milton, and with it but in part, endeav- ors by this method to deepen and clarify the apprecia- tion of his art and teaching. My interest in the present work has found support and encouragement in the opinions of Mr. Churton Collins, as expressed in his valuable book. -

From the Fjords to the Nile. Essays in Honour of Richard Holton Pierce

From the Fjords to the Nile brings together essays by students and colleagues of Richard Holton Pierce (b. 1935), presented on the occasion of his 80th birthday. It covers topics Steiner, Tsakos and Seland (eds) on the ancient world and the Near East. Pierce is Professor Emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Bergen. Starting out as an expert in Egyptian languages, and of law in Greco-Roman Egypt, his professional interest has spanned from ancient Nubia and Coptic Egypt, to digital humanities and game theory. His contribution as scholar, teacher, supervisor and informal advisor to Norwegian studies in Egyptology, classics, archaeology, history, religion, and linguistics through more than five decades can hardly be overstated. Pål Steiner has an MA in Egyptian archaeology from K.U. Leuven and an MA in religious studies from the University of Bergen, where he has been teaching Ancient Near Eastern religions. He has published a collection of Egyptian myths in Norwegian. He is now an academic librarian at the University of Bergen, while finishing his PhD on Egyptian funerary rituals. Alexandros Tsakos studied history and archaeology at the University of Ioannina, Greece. His Master thesis was written on ancient polytheisms and submitted to the Université Libre, Belgium. He defended his PhD thesis at Humboldt University, Berlin on the topic ‘The Greek Manuscripts on Parchment Discovered at Site SR022.A in the Fourth Cataract Region, North Sudan’. He is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bergen with the project ‘Religious Literacy in Christian Nubia’. He From the Fjords to Nile is a founding member of the Union for Nubian Studies and member of the editorial board of Dotawo.