Motivation and Emotion 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship of PSAT/NMSQT Scores and AP Examination Grades

Research Notes Office of Research and Development RN-02, November 1997 The Relationship of PSAT/NMSQT Scores and AP® Examination Grades he PSAT/NMSQT, which measures devel- Recent analyses have shown that student per- oped verbal and quantitative reasoning, as formance on the PSAT/NMSQT can be useful in Twell as writing skills generally associated identifying additional students who may be suc- with academic achievement in college, is adminis- cessful in AP courses. PSAT/NMSQT scores can tered each October to nearly two million students, identify students who may not have been initially the vast majority of whom are high school juniors considered for an AP course through teacher or and sophomores. PSAT/NMSQT information has self-nomination or other local procedures. For been used by high school counselors to assist in many AP courses, students with moderate scores advising students in college planning, high school on the PSAT/NMSQT have a high probability of suc- course selection, and for scholarship awards. In- cess on the examinations. For example, a majority formation from the PSAT/NMSQT can also be very of students with PSAT/NMSQT verbal scores of useful for high schools in identifying additional 46–50 received grades of 3 or above on nearly all of students who may be successful in Advanced the 29 AP Examinations studied, while over one- Placement courses, and assisting schools in deter- third of students with scores of 41–45 achieved mining whether to offer additional Advanced grades of 3 or above on five AP Examinations. Placement courses. There are substantial variations across AP subjects that must be considered. -

AP Psychology Essential Information

AP Psychology Essential Information Introduction to Psychology 1. What is the definition of psychology? a. The study of behavior and mental processes 2. How did psychology as a study of behavior and mental processes develop? a. The roots of psychology can be traced back to the philosophy of Empiricism: emphasizing the role of experience and evidence, especially sensory perception, in the formation of ideas, while discounting the notion of innate ideas.- Greeks like Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. Later studied by Francis Bacon, Rene Decartes and John Locke. 3. What is the historical development of psychology? a. The evolution of psychology includes structuralism, functionalism, psychoanalysis, behaviorism and Gestalt psychology b. Wilhelm Wundt: set up the first psychological laboratory. i. trained subjects in introspection: examine your own cognitive processing- known as structuralism ii. study the role of consciousness; changes from philosophy to a science ii. Also used by Edward Titchener c. William James: published first psychology textbook; examined how the structures identified by Wundt function in our lives- functionalism i. Based off of Darwin’s theory of evolution 4. What are the different approaches to studying behavior and mental processes? a. biological, evolutionary, psychoanalysis (Freud), behavioral (Watson, Ivan Pavlov, B.F. Skinner), cognitive, humanistic (Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers), social (Bandura) and Gestalt 5. Who are the individuals associated with different approaches to psychology? a. Darwin, Freud, Watson, Skinner and Maslow 6. What are each of the subfields within psychology? a. cognitive, biological, personality, developmental, quantitative, clinical, counseling, psychiatry, community, educational, school, social, industrial Methods and Testing 1. What are the two main forms of research? a. -

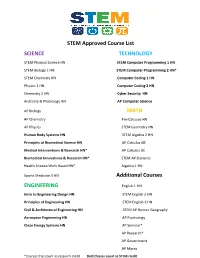

STEM Approved Course List SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY

STEM Approved Course List SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY STEM Physical Science HN STEM Computer Programming 1 HN STEM Biology 1 HN STEM Computer Programming 2 HN* STEM Chemistry HN Computer Coding 1 HN Physics 1 HN Computer Coding 2 HN Chemistry 2 HN Cyber Security HN Anatomy & Physiology HN AP Computer Science AP Biology MATH AP Chemistry Pre-Calculus HN AP Physics STEM Geometry HN Human Body Systems HN STEM Algebra 2 HN Principles of Biomedical Science HN AP Calculus AB Medical Interventions & Research HN* AP Calculus BC Biomedical Innovations & Research HN* STEM AP Statistics Health Science Work Based HN* Algebra 1 HN Sports Medicine 3 HN Additional Courses ENGINEERING English 1 HN Intro to Engineering Design HN STEM English 2 HN Principles of Engineering HN STEM English 3 HN Civil & Architectural Engineering HN STEM AP Human Geography Aerospace Engineering HN AP Psychology Clean Energy Systems HN AP Seminar* AP Research* AP Government AP Macro *Courses that count as research credit Bold Classes count as STEM credit Program Requirements: To qualify for recognition as a STEM Scholar, and receive the program designation for recommendations/applications for colleges and scholarships the STEM student shall: 1. Attain eight STEM credits from the approved courses list below. a. Each year-long Honors/AP/dual credit course from the approved list is a single STEM credit. b. The final grade in the class must be 80 or above to count as a STEM credit. 2. Successfully complete a research course from the approved courses list below. 3. Complete and have approved quality credit documentation each year in the program. -

AP Psychology

AP Psychology Course Description: The curriculum for this course is developed from the College Board AP Psychology Curriculum because it is designed to be the equivalent of a one semester introductory college or university Introduction to Psychology course. This is an elective social studies course. Due to the fact that this course is advanced, it is also weighted at 1.0. Students who take Advanced Placement Psychology can earn up to three college credits by taking the AP Exam. Taking the College Board exam is not a course requirement and students must pay the approximately $95 fee associated with the exam. During this class we will explore the following 9 units: Scientific Foundations of Psychology, Biological Base of Behavior, Sensation and Perception, Learning, Cognitive Psychology, Developmental Psychology, Motivation, Emotion and Personality, Clinical Psychology and Social Psychology. We will study the major core concepts and theories of psychology as well as practice the basic skills of conducting and analyzing psychological research. Students will develop their critical thinking skills through reading, writing and discussion. They will also be required to apply psychological concepts to authentic contexts as well as their own lives. The information in this course overview outlines what students should understand and be able to do by the end of the year. Mastery Standards Skill Category 1: Concept Understanding - Students will be able to define, explain, and apply psychological concepts, behavior, theories and perspectives. ● Define and/or apply concepts (1.A) ● Explain behavior in authentic context (1.B) ● Apply theories and perspectives in authentic contexts (1.C) Skill Category 2: Data Analysis - Students will be able to analyze and interpret quantitative data. -

Motivation and Emotion AP Psychology

What plays a bigger role in directing our behavior, Psychology or Physiology? Defend your position! 1 On Socrative! Motivation and Emotion AP Psychology 2 Where Do We Begin? • Motivation – a psychological process that directs and maintains your behavior toward a goal. • Motives are the needs, wants, interests, and desires that propel or drive people in certain directions. • Interview 3 Motivational Concepts (Theories) •Instinct •Drive Reduction •Incentive •Hierarchy of needs •Homeostasis (hunger-thirst) 4 Motivation and Instinct . Motivation . Most of the time is learned – we are motivated by different things. Instinct . complex behavior that is rigidly patterned throughout a species and is unlearned 5 Biological and Social Motives • Biological Motives • Social Motives • Hunger • Achievement • Thirst • Order • Sex • Play • Sleep • Autonomy • Excretory • Affiliation 6 Drive Reduction Theory: . Drive-Reduction Theory . When individuals experience a need or drive, they’re motivated to reduce that need or drive. • Drive theories assume that people are always trying to reduce internal tension. • Therefore, drive theories believe that the source of motivation lies within the person (not from the environment) Need Drive-reducing Drive (e.g., for behaviors (hunger, thirst) food, water) (eating, drinking) 7 Carl is stranded on a deserted island. He spends his day looking for fresh water. His desire to find water would be considered a: 1. Drive 2. Need 3. Want 4. Drive reduction trait 5. Both 1 and 2 8 Motivation • A Drive is an internal state of tension that motivates us to engage in activities that reduce this tension. • Our bodies strive to keep somewhat constant. Homeostasis . Sometimes we HAVE to reduce the drive (dying of thirst, hunger, etc.) – we might not have a choice. -

Psychology Major & Cas Requirements

DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGICAL & BRAIN SCIENCES http://www.bu.edu/psych/ PSYCHOLOGY MAJOR & CAS REQUIREMENTS FOR CONTINUING STUDENTS WHO ENTERED PRIOR TO AY 18/19 AND TRANSFER STUDENTS WHO ENTERED PRIOR TO AY 20/21 The Psychology Concentration Requirements: 1. PS 101 or a score of 4 or 5 on the AP Psychology Exam. 2. Nine Principal Psychology Courses: PS 231: Physiological Psychology. Please note: • NE 101 (Introduction to Neuroscience) will count in place of PS 231 (Physiological Psychology) if a student took NE 101 prior to declaring their psychology major, or was a previous neuroscience major who switched to psychology, or is a current neuroscience/psychology double major. • All students who are psychology majors, and do not fall into one of the categories above, need to take PS231. • Students will not be awarded credit for both courses. Students may receive credit for PS 231 or NE 101, but not both. Eight Additional Principal Courses (Four or more must be selected from the 300 level or above) The choice of principal courses must include at least two courses from each of the broad content groups listed below. Group A Group B PS 222 Perception PS 241 Developmental Psych PS 234 Psych of Learning PS 251 Psych of Personality PS 333 Drugs and Behavior PS 261 Social Psych PS 336 Intro to Cognitive Psych PS 370 Psych of the Family PS 337 Systems of the Brain PS 371 Abnormal Psych PS 338 Neuropsych PS 339 Cognitive Neuroscience 1. (PS) 5. *Experimental 2. (PS) 6. (PS 300+) 3. (PS) 7. (PS 300+) 4. -

MOTIVATION ANE~ EMOTION Motivation

DEMIDEC~ AP Psychology Cram Kit I 44 MOTIVATION ANE~ EMOTION Motivation THEORIES OF MOTIVATION HIERARCHY OF NEEDS WHAT YOU WANT AND WHAT YOU NEED CLIMBING THE PYRAMID Motivations are the needs and desires that cause Abraham Maslow created a hierarchy of needs, behaviors—the reasons people do the things they do. predicting the order in which needs must be satisfied. Intrinsic motivation comes from within oneself, while extrinsic motivation is drawn from the outside world. Self-actualization > DRIVE REDUCTION THEORY People are motivated by biological needs • Drives are impulses to meet those needs in order to achieve homeostasis, a state of internal balance Safety and securit • Primary drives are biological needs (food, shelter) Survival and physiological needs • Secondary drives are used to meet primary drives (money, acceptance) INSTINCT THEORY HUNGER AND EATING DISORDERS • People perform species-specific behaviors THROUGH THICK AND THIN • Instincts are inborn behaviors necessary for survival Hunger is determined by an empty stomach and body INCENTIVE THEORY chemistry (glucose and insulin). The hypothalamus • People perform some behaviors based on desire, helps stimulate and satiate hunger. Set-point theory rather than need states that the hypothalamus maintains the body’s optimum body weight by determining the metabolic • Incentives are stimuli associated with rewards rate. Eating disorders are psychological problems OPPONENT PROCESS THEORY related to weight, body image, and eating habits. • People begin at a baseline level of motivation SEX • Performing pleasurable behaviors moves people away from the baseline, but an opponent process THE BIRDS AND THE BEES motivates them to return to the neutral state Humans are driven to procreate in order to pass on • This theory is often used to explain addiction: their genes. -

AP Psychology Course Syllabus 2020 - 2021 Teacher: Mrs

AP Psychology Course Syllabus 2020 - 2021 Teacher: Mrs. Tobii Mason Email Address: [email protected] Room: 2100 (Pd. 1 & 4) MyMCPS Classroom: Has Zoom meeting times & links Course Description: The Advanced Placement Psychology course is designed to introduce students to the systematic and scientific study of the behavior and mental processes of human beings and other animals. Students are exposed to the psychological facts, principles, and phenomena associated with each of the major subfields within psychology. They also learn about the ethics and methods psychologists use in their science and practice. The Advanced Placement Psychology course will offer students the opportunities to learn about the explorations and discoveries made by psychologists over the past century. Students will get the chance to assess some of the differing approaches adopted by psychologists, including biological, behavioral, cognitive, humanistic, psychodynamic, and sociocultural perspectives. Students will also learn the basic skills of psychology research and develop critical thinking skills. The Advanced Placement Psychology course aims to provide students with a learning experience equivalent to that of most college introductory psychology courses. This course will prepare students to successfully conquer the AP Psychology Exam. Textbook: Myers, David G. Myers’ Psychology for AP, 2nd Edition, New York, Worth, 2014 Textbooks will be assigned during the first month of school. Reading assignments in the textbook will be given out weekly. Suggested Additional Resources: nd ● Strive for 5: Preparing for the AP Psychology Examination, 2 Edition, Worth, 2014 (ISBN-10: 1464156050) ● Free and Open Resources on the Online textbook website, accessed through http://www.macmillanlearning.com/Catalog/studentresources/MyersAP2e ● Any AP Psychology Exam Prep / Review Book My Distance Learning Expectations: 1. -

AP Psychology Course Description

psychology Course Description Effective Fall 2 0 1 3 AP Course Descriptions are updated regularly. Please visit AP Central ® (apcentral.collegeboard.org) to determine whether a more recent Course Description PDF is available. Inside Front cover TheCollegeBoard The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators, and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. APEquityandAccessPolicy The College Board strongly encourages educators to make equitable access a guiding principle for their AP programs by giving all willing and academically prepared students the opportunity to participate in AP. We encourage the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP for students from ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underserved. Schools should make every effort to ensure their AP classes reflect the diversity of their student population. The College Board also believes that all students should have access to academically challenging course work before they enroll in AP classes, which can prepare them for AP success. -

AP Psychology Course Syllabus 2020 - 2021 Teacher: Ms

AP Psychology Course Syllabus 2020 - 2021 Teacher: Ms. Katarina Pisini Email Address: [email protected] Room: 2005 (Pd. 3, 5 & 7) MyMCPS Classroom: Has Zoom meeting times & links Course Description: The Advanced Placement Psychology course is designed to introduce students to the systematic and scientific study of the behavior and mental processes of human beings and other animals. Students are exposed to the psychological facts, principles, and phenomena associated with each of the major subfields within psychology. They also learn about the ethics and methods psychologists use in their science and practice. The Advanced Placement Psychology course will offer students the opportunities to learn about the explorations and discoveries made by psychologists over the past century. Students will get the chance to assess some of the differing approaches adopted by psychologists, including biological, behavioral, cognitive, humanistic, psychodynamic, and sociocultural perspectives. Students will also learn the basic skills of psychology research and develop critical thinking skills. The Advanced Placement Psychology course aims to provide students with a learning experience equivalent to that of most college introductory psychology courses. This course will prepare students to successfully conquer the AP Psychology Exam. Textbook: Myers, David G. Myers’ Psychology for AP, 2nd Edition, New York, Worth, 2014 Textbooks will be assigned during the first month of school. Reading assignments in the textbook will be given out weekly. Suggested Additional Resources: nd ● Strive for 5: Preparing for the AP Psychology Examination, 2 Edition, Worth, 2014 (ISBN-10: 1464156050) ● Free and Open Resources on the Online textbook website, accessed through http://www.macmillanlearning.com/Catalog/studentresources/MyersAP2e ● Any AP Psychology Exam Prep / Review Book My Distance Learning Expectations: 1. -

The AP® Program: Resources for Parents and Families

I chose to take AP courses because I love to challenge myself ... I feel thoroughly prepared for college because of the rigor of my AP classes. Anica, Senior, Denver The AP® Program: Resources for Parents and Families In 2013, over 1 million U.S. public high school graduates took at least one AP Exam.1 What Is AP? Benefts of AP The College Board’s Advanced Placement Program® (AP®) enables willing and academically prepared students to pursue college-level studies — with the opportunity to earn college credit, advanced 1 AP can set students apart in the college admission process. placement or both — while still in high school. AP Exams are given each year in May. A score of 3 Students who take AP courses send a signal to colleges that they’re serious about their or higher on an AP Exam can typically earn students college credit and/or placement into advanced education and that they’re willing to challenge themselves with rigorous course work. Eighty-fve courses in college. percent of selective colleges and universities report that a student’s AP experience favorably impacts admission decisions2. Myth Reality AP is for students who always get AP courses are for any student who is academically 2 The fnancial benefts of AP are important to consider. good grades. prepared and motivated to take on college-level courses. Students who take fve years or more to graduate can spend $21,500 for each additional year in college, to cover tuition, fees, living expenses, transportation and other costs3. Research shows that Many schools use GPA weighting to acknowledge the students who take AP courses and exams are much more likely than their peers to complete a college additional effort required by AP. -

AP Psychology Summer Assignment

Shrager AP Psychology Summer Assignment Welcome to Advanced Placement Psychology at Hopewell Valley Central High School in 2021- 2022, the inaugural offering of this course! You are brave and intrepid learners indeed! You will have the opportunity to find out what makes people tick and perhaps have a better understanding of yourself as well. During the 2021-2022 school year we will be exploring the world of psychology, improving our research/writing skills and preparing for the AP Examination in the spring. Successful completion of this course will yield a greater understanding of psychology, yourself, and the world around you. It is also the goal to prepare you for the content, format, and rigor of a college level course and examination. In truth, I never liked summer assignments. I believe summer should be a time to re-charge and relax. However, in the world of AP classes, we have to face a very stark reality: we start school much later than most of the country, yet we all take AP exams on the same day. Simply, we have less time to learn the material and prepare for the exam than most of the nation. Summer assignments are essential in an AP course so we can hit the ground running in September. This Summer assignment is due to Mr. Shrager in class on the first day of school. As you work, if you have any questions, trouble with links, or just want to “talk psychology” feel free to email [email protected]. Summer Scavenger Hunt: Getting to Know Psychology Directions: Complete the following questions as an introduction to psychology.