Fungus-Bacteria Interactions in Decomposing Wood: Unravelling Community Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

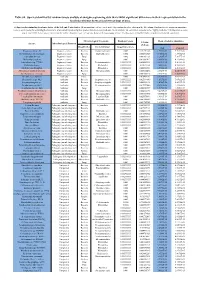

Table S5. the Information of the Bacteria Annotated in the Soil Community at Species Level

Table S5. The information of the bacteria annotated in the soil community at species level No. Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species The number of contigs Abundance(%) 1 Firmicutes Bacilli Bacillales Bacillaceae Bacillus Bacillus cereus 1749 5.145782459 2 Bacteroidetes Cytophagia Cytophagales Hymenobacteraceae Hymenobacter Hymenobacter sedentarius 1538 4.52499338 3 Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadales Gemmatimonadaceae Gemmatirosa Gemmatirosa kalamazoonesis 1020 3.000970902 4 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas indica 797 2.344876284 5 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Streptococcaceae Lactococcus Lactococcus piscium 542 1.594633558 6 Actinobacteria Thermoleophilia Solirubrobacterales Conexibacteraceae Conexibacter Conexibacter woesei 471 1.385742446 7 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas taxi 430 1.265115184 8 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas wittichii 388 1.141545794 9 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas sp. FARSPH 298 0.876754244 10 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sorangium cellulosum 260 0.764953367 11 Proteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria Myxococcales Polyangiaceae Sorangium Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 260 0.764953367 12 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas panacis 252 0.741416341 -

Improved Efficiency in Screening.Pdf

PLEASE NOTE! THIS IS SELF-ARCHIVED FINAL-DRAFT VERSION OF THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE To cite this Article: Kinnunen, A. Maijala, P., Järvinen, P. & Hatakka, A. 2017. Improved efficiency in screening for lignin-modifying peroxidases and laccases of basidiomycetes. Current Biotechnology 6 (2), 105–115. doi: 10.2174/2211550105666160330205138 URL:http://www.eurekaselect.com/140791/article Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] Current Biotechnology, 2016, 5, 000-000 1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Improved Efficiency in Screening for Lignin-Modifying Peroxidases and Laccases of Basidiomycetes Anu Kinnunen1, Pekka Maijala2, Päivi Järvinen3 and Annele Hatakka1,* aDepartment of Food and Environmental Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry, University of Helsinki, Finland; bSchool of Food and Agriculture, Applied University of Seinäjoki, Seinäjoki, Finland; cCentre for Drug Research, Division of Pharmaceutical Biosciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Helsinki, Finland Abstract: Background: Wood rotting white-rot and litter-decomposing basidiomycetes form a huge reservoir of oxidative enzymes, needed for applications in the pulp and paper and textile industries and for bioremediation. Objective: The aim was (i) to achieve higher throughput in enzyme screening through miniaturization and automatization of the activity assays, and (ii) to discover fungi which produce efficient oxidoreductases for industrial purposes. Methods: Miniaturized activity assays mostly using dyes as substrate were carried Annele Hatakka A R T I C L E H I S T O R Y out for lignin peroxidase, versatile peroxidase, manganese peroxidase and laccase. Received: November 24, 2015 Methods were validated and 53 species of basidiomycetes were screened for lignin modifying enzymes Revised: March 15, 2016 Accepted: March 29, 2016 when cultivated in liquid mineral, soy, peptone and solid state oat husk medium. -

A Preliminary Checklist of Arizona Macrofungi

A PRELIMINARY CHECKLIST OF ARIZONA MACROFUNGI Scott T. Bates School of Life Sciences Arizona State University PO Box 874601 Tempe, AZ 85287-4601 ABSTRACT A checklist of 1290 species of nonlichenized ascomycetaceous, basidiomycetaceous, and zygomycetaceous macrofungi is presented for the state of Arizona. The checklist was compiled from records of Arizona fungi in scientific publications or herbarium databases. Additional records were obtained from a physical search of herbarium specimens in the University of Arizona’s Robert L. Gilbertson Mycological Herbarium and of the author’s personal herbarium. This publication represents the first comprehensive checklist of macrofungi for Arizona. In all probability, the checklist is far from complete as new species await discovery and some of the species listed are in need of taxonomic revision. The data presented here serve as a baseline for future studies related to fungal biodiversity in Arizona and can contribute to state or national inventories of biota. INTRODUCTION Arizona is a state noted for the diversity of its biotic communities (Brown 1994). Boreal forests found at high altitudes, the ‘Sky Islands’ prevalent in the southern parts of the state, and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa P.& C. Lawson) forests that are widespread in Arizona, all provide rich habitats that sustain numerous species of macrofungi. Even xeric biomes, such as desertscrub and semidesert- grasslands, support a unique mycota, which include rare species such as Itajahya galericulata A. Møller (Long & Stouffer 1943b, Fig. 2c). Although checklists for some groups of fungi present in the state have been published previously (e.g., Gilbertson & Budington 1970, Gilbertson et al. 1974, Gilbertson & Bigelow 1998, Fogel & States 2002), this checklist represents the first comprehensive listing of all macrofungi in the kingdom Eumycota (Fungi) that are known from Arizona. -

Aegis Boa (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) a New Neotropical Genus and Species Based on Morphological Data and Phylogenetic Evidences

Mycosphere 8(6): 1261–1269 (2017) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/8/6/11 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Aegis boa (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) a new neotropical genus and species based on morphological data and phylogenetic evidences Gómez-Montoya N1, Rajchenberg M2 and Robledo GL 1, 3* 1 Laboratorio de Micología, Instituto Multidisciplinario de Biología Vegetal, Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, CC 495, CP 5000 Córdoba, Argentina 2 Centro de Investigación y Extensión Forestal Andino Patagónico (CIEFAP), C.C. 14, 9200 Esquel, Chubut and Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia S.J. Bosco, Ingeniería Forestal, Ruta 259 km 14.6, Esquel, Chubut, Argentina 3 Fundación FungiCosmos, Av. General Paz 54, 4to piso, of. 4, CP 5000, Córdoba, Argentina. Gómez-Montoya N, Rajchenberg M, Robledo GL. 2017 – Aegis boa (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) a new neotropical genus and species based on morphological data and phylogenetic evidences. Mycosphere 8(6), 1261–1269, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/8/6/11 Abstract The new genus, Aegis Gómez-Montoya, Rajchenb. & Robledo, is described to accommodate the new species Aegis boa based on morphological data and phylogenetic evidences (ITS – LSU rDNA). It is characterized by a particular monomitic hyphal system with thick-walled, widening, inflated and constricted generative hyphae, and allantoid basidiospores. Phylogenetically Aegis is closely related to Antrodiella aurantilaeta, both species presenting an isolated position within Polyporales into Grifola clade. The new taxon is so far known from Yungas Mountain Rainforests of NW Argentina. Key words – Grifola – Neotropical polypores – Tyromyces Introduction Polypore diversity of NW Argentina was reviewed by Robledo & Rajchenberg (2007). -

Phanerochaete Porostereoides, a New Species in the Core Clade with Brown Generative Hyphae from China

Mycosphere 7 (5): 648–655 (2016) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/7/5/10 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Phanerochaete porostereoides, a new species in the core clade with brown generative hyphae from China Liu SL1 and He SH1* 1 Institute of Microbiology, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing 100083, China Liu SL, He SH 2016 – Phanerochaete porostereoides, a new species in the core clade with brown generative hyphae from China. Mycosphere 7(5), 648–655, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/7/5/10 Abstract A new species, Phanerochaete porostereoides, is described and illustrated from northwestern China based on the morphological and molecular evidence. It is characterized by a effused brown basidiocarp, a monomitic hyphal system, yellowish brown generative hyphae without clamp connections, numerous hyphal ends in hymenium and subhymenium, and small ellipsoid basidiospores 4.7–5.3 × 2.5–3.1 µm. Morphologically, P. porostereoides resembles Porostereum, but phylogenetic analyses inferred from the combined sequences of ITS and nLSU show that it is nested within the Phanerochaete s.s. clade, and not closely related to Porostereum spadiceum, type of the genus. Key words – Porostereum – taxonomy – wood-inhabiting fungi Introduction Phanerochaete P. Karst., typified by Thelephora velutina DC., is a widespread genus, and characterized by the membranaceous basidiocarps, a monomitic hyphal system, simple-septate generative hyphae (single or multiple clamps may present in subiculum), clavate basidia and smooth thin-walled inamyloid basidiospores (Eriksson et al. 1978, Burdsall 1985, Bernicchia & Gorjón 2010, Wu et al. 2010). Recent molecular research (de Koker et al. 2003, Wu et al. -

Draft Genome Sequences of Three Fungal-Interactive Paraburkholderia

Pratama et al. Standards in Genomic Sciences (2017) 12:81 DOI 10.1186/s40793-017-0293-8 EXTENDED GENOME REPORT Open Access Draft genome sequences of three fungal-interactive Paraburkholderia terrae strains, BS007, BS110 and BS437 Akbar Adjie Pratama1* , Irshad Ul Haq1, Rashid Nazir2, Maryam Chaib De Mares1 and Jan Dirk van Elsas1* Abstract Here, we report the draft genome sequences of three fungal-interactive Paraburkholderia terrae strains, denoted BS110, BS007 and BS437. Phylogenetic analyses showed that the three strains belong to clade II of the genus Burkholderia, which was recently renamed Paraburkholderia. This novel genus primarily contains environmental species, encompassing non-pathogenic plant- as well as fungal-interactive species. The genome of strain BS007 consists of 11,025,273 bp, whereas those of strains BS110 and BS437 have 11,178,081 and 11,303,071 bp, respectively. Analyses of the three annotated genomes revealed the presence of (1) a large suite of substrate capture systems, and (2) a suite of genetic systems required for adaptation to microenvironments in soil and the mycosphere. Thus, genes encoding traits that potentially confer fungal interactivity were found, such as type 4 pili, type 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 secretion systems, and biofilm formation (PGA, alginate and pel) and glycerol uptake systems. Furthermore, the three genomes also revealed the presence of a highly conserved five-gene cluster that had previously been shown to be upregulated upon contact with fungal hyphae. Moreover, a considerable number of prophage-like and CRISPR spacer sequences was found, next to genetic systems responsible for secondary metabolite production. Overall, the three P. -

An Overview of Aphyllophorales (Wood Rotting Fungi) from India

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2013) 2(12): 112-139 ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 2 Number 12 (2013) pp. 112-139 http://www.ijcmas.com Review Article An overview of Aphyllophorales (wood rotting fungi) from India Kiran Ramchandra Ranadive* Waghire College, Saswad, Tal-Purandar, Dist. Pune, Maharashtra (India) *Corresponding author A B S T R A C T K e y w o r d s During field and literature surveys, a rich mycobiota was observed in the vegetation of India. The heavy rainfall and high humidity favours the growth of Fungi; Aphyllophoraceous fungi. The present work materially adds to our knowledge of Aphyllophorales; Poroid and Non-Poroid Aphyllophorales from all over India. A total of more than Basidiomycetes; 190 genera of 52 families and total 1175 species of from poroid and non-poroid semi-evergreen Aphyllophorales fungi were reported from Indian literature till 2012.The checklist gives the total count of aphyllophoraceous fungal diversity from India which is also forest.. a valued addition for comparing aphyllophoraceous diversity in the world. Introduction Aphyllophorales order was proposed by in culture are recognized by Stalper. Rea, after Patouillard, for Basidiomycetes (Stalper,1978). having macroscopic basidiocarps in which the hymenophore is flattened Much of the literature of the order is based (Thelephoraceae), club-like on the traditional family groupings and as (Clavariaceae), tooth-like (Hydnaceae) or under the current re-arrangements, one has the hymenium lining tubes family may exhibit several different types (Polyporaceae) or some times on lamellae, of hymenophore (e.g. Gomphaceae has the poroid or lamellate hymenophores effuse, clavarioid, hydnoid and being tough and not fleshy as in the cantharelloid hymenophores). -

Multi-Dimensional Mycelia Interactions

Multi-dimensional mycelia interactions A thesis submitted to Cardiff University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jade O’Leary, B.Sc (Hons) February 2018 DECLARATION This work has not been submitted in substance for any other degree or award at this or any other university or place of learning, nor is being submitted concurrently in candidature for any degree or other award. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. The views expressed are my own. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… STATEMENT 4: PREVIOUSLY APPROVED BAR ON ACCESS I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter- library loans after expiry of a bar on access previously approved by the Academic Standards & Quality Committee. Signed ………………………………………… (candidate) Date ………………………… i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Carsten Müller and Professor Dan Eastwood for all their time and advice, and especially Professor Lynne Boddy for her tireless dedication and infectious enthusiasm. Thanks to the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) for studentship NE/L00243/1 and for funding UHPLC-MS analyses at the NERC Biomolecular Analysis Facility, Birmingham (NBAF-B). -

Title: Finding Fungal Ecological Strategies: Is Recycling an Option? Amy E. Zanne1, Jeff R. Powell2, Habacuc Flores-Moreno1, E

Title: Finding fungal ecological strategies: Is recycling an option? Amy E. Zanne1, Jeff R. Powell2, Habacuc Flores-Moreno1, E. Toby Kiers3, Anouk van ’t Padje3, William K. Cornwell4 1Biological Sciences, George Washington University, Washington, DC, 20052, USA 2Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, Western Sydney University, Penrith, NSW, 2751, Australia 3Department of Ecological Science, Vrije Universiteit, De Boelelaan 108, 1081 HV Amsterdam, the Netherlands 4Evolution & Ecology Research Centre, School of Biological Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia Address for manuscript correspondence: Department of Biological Sciences, George Washington University, Science and Engineering Hall, 800 22nd Street NW, Suite 6000, Washington, DC 20052 USA; Phone: +12029948751; E-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract: High-throughput sequencing (e.g., amplicon and shotgun) has provided new insight into the diversity and distribution of fungi around the globe, but developing a framework to understand this diversity has proved challenging. Here we review key ecological strategy theories developed for macro-organisms and discuss ways that they can be applied to fungi. We suggest that while certain elements may be applied, an easy translation does not exist. Particular aspects of fungal ecology, such as body size and growth architecture, which are critical to many existing strategy schemes, as well as guild shifting, need special consideration in fungi. Moreover, data on shifts in traits across environments, important to the development of strategy schemes for macro-organisms, also does not yet exist for fungi. We end by suggesting a way forward to add data. Additional data can open the door to the development of fungi- specific strategy schemes and an associated understanding of the trait and ecological strategy dimensions employed by the world’s fungi. -

Molecular Signatures and Phylogenomic Analysis Of

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 19 December 2014 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00429 Molecular signatures and phylogenomic analysis of the genus Burkholderia: proposal for division of this genus into the emended genus Burkholderia containing pathogenic organisms and a new genus Paraburkholderia gen. nov. harboring environmental species Amandeep Sawana , Mobolaji Adeolu and Radhey S. Gupta* Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences, Health Sciences Center, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada Edited by: The genus Burkholderia contains large number of diverse species which include many Scott Norman Peterson, Sanford clinically important organisms, phytopathogens, as well as environmental species. Burnham Medical Research However, currently, there is a paucity of biochemical or molecular characteristics which can Institute, USA reliably distinguish different groups of Burkholderia species. We report here the results Reviewed by: Loren John Hauser, Oak Ridge of detailed phylogenetic and comparative genomic analyses of 45 sequenced species National Laboratory, USA of the genus Burkholderia. In phylogenetic trees based upon concatenated sequences William Charles Nierman, J. Craig for 21 conserved proteins as well as 16S rRNA gene sequence based trees, members Venter Institute, USA of the genus Burkholderia grouped into two major clades. Within these main clades *Correspondence: a number of smaller clades including those corresponding to the clinically important Radhey S. Gupta, Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) and the Burkholderia pseudomallei groups were also Sciences, Health Sciences Center, clearly distinguished. Our comparative analysis of protein sequences from Burkholderia McMaster University, 1200 Main spp. has identified 42 highly specific molecular markers in the form of conserved sequence Street West, Hamilton, ON L8N indels (CSIs) that are uniquely found in a number of well-defined groups of Burkholderia 3Z5, Canada e-mail: [email protected] spp. -

Table S8. Species Identified by Random Forests Analysis of Shotgun Sequencing Data That Exhibit Significant Differences In

Table S8. Species identified by random forests analysis of shotgun sequencing data that exhibit significant differences in their representation in the fecal microbiomes between each two groups of mice. (a) Species discriminating fecal microbiota of the Soil and Control mice. Mean importance of species identified by random forest are shown in the 5th column. Random forests assigns an importance score to each species by estimating the increase in error caused by removing that species from the set of predictors. In our analysis, we considered a species to be “highly predictive” if its importance score was at least 0.001. T-test was performed for the relative abundances of each species between the two groups of mice. P-values were at least 0.05 to be considered statistically significant. Microbiological Taxonomy Random Forests Mean of relative abundance P-Value Species Microbiological Function (T-Test) Classification Bacterial Order Importance Score Soil Control Rhodococcus sp. 2G Engineered strain Bacteria Corynebacteriales 0.002 5.73791E-05 1.9325E-05 9.3737E-06 Herminiimonas arsenitoxidans Engineered strain Bacteria Burkholderiales 0.002 0.005112829 7.1580E-05 1.3995E-05 Aspergillus ibericus Engineered strain Fungi 0.002 0.001061181 9.2368E-05 7.3057E-05 Dichomitus squalens Engineered strain Fungi 0.002 0.018887472 8.0887E-05 4.1254E-05 Acinetobacter sp. TTH0-4 Engineered strain Bacteria Pseudomonadales 0.001333333 0.025523638 2.2311E-05 8.2612E-06 Rhizobium tropici Engineered strain Bacteria Rhizobiales 0.001333333 0.02079554 7.0081E-05 4.2000E-05 Methylocystis bryophila Engineered strain Bacteria Rhizobiales 0.001333333 0.006513543 3.5401E-05 2.2044E-05 Alteromonas naphthalenivorans Engineered strain Bacteria Alteromonadales 0.001 0.000660472 2.0747E-05 4.6463E-05 Saccharomyces cerevisiae Engineered strain Fungi 0.001 0.002980726 3.9901E-05 7.3043E-05 Bacillus phage Belinda Antibiotic Phage 0.002 0.016409765 6.8789E-07 6.0681E-08 Streptomyces sp. -

Black Cherry (Prunus Serotina Ehrh.) Colonization by Macrofungi in the Fourth Season of Its Decline Due to Different Control Measures in the Kampinos National Park

Folia Forestalia Polonica, Series A – Forestry, 2020, Vol. 62 (2), 78–87 ORIGINAL ARTICLE DOI: 10.2478/ffp-2020-0009 Black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) colonization by macrofungi in the fourth season of its decline due to different control measures in the Kampinos National Park Katarzyna Marciszewska1 , Andrzej Szczepkowski2, Anna Otręba3 1 Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Institute of Forest Sciences, Department of Forest Botany, Nowoursynowska 159, 02-776 Warsaw, Poland, e-mail: [email protected] 2 Warsaw University of Life Sciences – SGGW, Institute of Forest Sciences, Department of Forest Protection and Ecology, Nowoursynowska 159, 02-776 Warsaw, Poland 3 Kampinos National Park, Tetmajera 38, 05-080 Izabelin, Poland AB STRACT The experiment conducted in the Kampinos National Park since 2015 was aimed at assessing the sprouting ability of black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) in response to different measures of mechanical control and mycobiota coloniz- ing the dying trees. Basal cut-stump, cutting at ca. 1 m above the ground and girdling were performed on 4 terms, two plots and applied to 25 trees, 600 trees in total. Sprouts were removed every 8 weeks since the initial treatment for 4 consecutive growing seasons, except winter-treated trees. At the end of the fourth season of control, 515 out of 600 trees were dead (86%): 81% on Lipków and 90% on Sieraków plot. Among 18 experiment variants with sprouts removal, 17 showed more than 80% of dead trees. The lowest, 76% share, concerned summer cut-stump at the base of the tree. For winter measures, the share of dead trees was lower in all cases and ranged from 28% to 64% proving that sprouts removal contributes to the drop of sprouting strength and quicker dying of the trees.