A Preliminary Checklist of Arizona Macrofungi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Universidad De Concepción Facultad De Ciencias Naturales Y

Universidad de Concepción Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas Programa de Magister en Ciencias mención Botánica DIVERSIDAD DE MACROHONGOS EN ÁREAS DESÉRTICAS DEL NORTE GRANDE DE CHILE Tesis presentada a la Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Oceanográficas de la Universidad de Concepción para optar al grado de Magister en Ciencias mención Botánica POR: SANDRA CAROLINA TRONCOSO ALARCÓN Profesor Guía: Dr. Götz Palfner Profesora Co-Guía: Dra. Angélica Casanova Mayo 2020 Concepción, Chile AGRADECIMIENTOS Son muchas las personas que han contribuido durante el proceso y conclusión de este trabajo. En primer lugar quiero agradecer al Dr. Götz Palfner, guía de esta tesis y mi profesor desde el año 2014 y a la Dra. Angélica Casanova, quienes con su experiencia se han esforzado en enseñarme y ayudarme a llegar a esta instancia. A mis compañeros de laboratorio, Josefa Binimelis, Catalina Marín y Cristobal Araneda, por la ayuda mutua y compañía que nos pudimos brindar en el laboratorio o durante los viajes que se realizaron para contribuir a esta tesis. A CONAF Atacama y al Proyecto RT2716 “Ecofisiología de Líquenes Antárticos y del desierto de Atacama”, cuyas gestiones o financiamientos permitieron conocer un poco más de la diversidad de hongos y de los bellos paisajes de nuestro desierto chileno. Agradezco al Dr. Pablo Guerrero y a todas las personas que enviaron muestras fúngicas desertícolas al Laboratorio de Micología para identificarlas y que fueron incluidas en esta investigación. También agradezco a mi familia, mis padres, hermanos, abuelos y tíos, que siempre me han apoyado y animado a llevar a cabo mis metas de manera incondicional. -

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

A New Species of Antrodia (Basidiomycota, Polypores) from China

Mycosphere 8(7): 878–885 (2017) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/8/7/4 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences A new species of Antrodia (Basidiomycota, Polypores) from China Chen YY, Wu F* Institute of Microbiology, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing 100083, China Chen YY, Wu F 2017 –A new species of Antrodia (Basidiomycota, Polypores) from China. Mycosphere 8(7), 878–885, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/8/7/4 Abstract A new species, Antrodia monomitica sp. nov., is described and illustrated from China based on morphological characters and molecular evidence. It is characterized by producing annual, fragile and nodulose basidiomata, a monomitic hyphal system with clamp connections on generative hyphae, hyaline, thin-walled and fusiform to mango-shaped basidiospores (6–7.5 × 2.3– 3 µm), and causing a typical brown rot. In phylogenetic analysis inferred from ITS and nLSU rDNA sequences, the new species forms a distinct lineage in the Antrodia s. l., and has a close relationship with A. oleracea. Key words – Fomitopsidaceae – phylogenetic analysis – taxonomy – wood-decaying fungi Introduction Antrodia P. Karst., typified with Polyporus serpens Fr. (=Antrodia albida (Fr.) Donk (Donk 1960, Ryvarden 1991), is characterized by a resupinate to effused-reflexed growth habit, white or pale colour of the context, a dimitic hyphal system with clamp connections on generative hyphae, hyaline, thin-walled, cylindrical to very narrow ellipsoid basidiospores which are negative in Melzer’s reagent and Cotton Blue, and causing a brown rot (Ryvarden & Melo 2014). Antrodia is a highly heterogeneous genus which is closely related to Fomitopsis P. -

Los Alamos National Laboratory, Bandelier National Monument, and Los Alamos County

LA-13384-MS A Survey of Macromycete Diversity at Los Alamos National Laboratory, Bandelier National Monument, and Los Alamos County A Preliminary Report Los Alamos NATIONAL LABORATORY Los Alamos National Laboratory is operated by the University of California for the United States Department of Energy under contract W-7405-ENG-36. Edited by Hector Hinojosa, Group CIC-1 Photocomposition by Belinda Gutierrez, Group ESH-20 Cover: A fire road leading away from the Pajarito Ski Hill area where high-altitude surveys took place. (Photo by Fran J. Rogers.) An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither The Regents of the University of California, the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by The Regents of the University of California, the United States Government, or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of The Regents of the University of California, the United States Government, or any agency thereof. Los Alamos National Laboratory strongly supports academic freedom and a researcher's right to publish; as an institution, however, the Laboratory does not endorse the viewpoint of a publication or guarantee its technical correctness. -

A New Species of Bondarzewia from India

Turkish Journal of Botany Turk J Bot (2015) 39: 128-133 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/botany/ © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1402-82 A new species of Bondarzewia from India 1, 1 2 Kanad DAS *, Arvind PARIHAR , Manoj Emanuel HEMBROM 1 Botanical Survey of India, Cryptogamic Unit, P. O. B. Garden, Howrah, India 2 Botanical Survey of India, Central National Herbarium, P. O. B. Garden, Howrah, India Received: 25.02.2014 Accepted: 18.07.2014 Published Online: 02.01.2015 Printed: 30.01.2015 Abstract: Bondarzewia zonata, collected from North Sikkim, is proposed here as new to science. It is characterized by basidiomata with strong zonate pilei, thin context turning persistent dark red with guaiacol, comparatively small spores with narrow ornamented ridges, and an absence of cystidioles. A detailed description coupled with macro- and micromorphological illustrations of this species is provided. Its relation to the allied species is discussed and a provisional key to the species of Bondarzewia is given. Key words: Macrofungi, Bondarzewia, Russulales, new species, taxonomy, Sikkim 1. Introduction Picea. After thorough macro- and micromorphological The genusBondarzewia was first described by Singer studies followed by a survey of the literature, it proved to (1940). Presently, it accommodates subtropical (Dai et be new to science. It is proposed as Bondarzewia zonata al., 2010) to temperate and wood-inhabiting parasitic and described here in detail with illustrations. Its relation (causing white rot) poroid macrofungi. Therefore, the with closely related taxa is also discussed. genus Bondarzewia can be characterized as pileate stipitate to substipitate basidiocarps, with a dimitic hyphal system 2. -

Basidiomycota) in Finland

Mycosphere 7 (3): 333–357(2016) www.mycosphere.org ISSN 2077 7019 Article Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/7/3/7 Copyright © Guizhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences Extensions of known geographic distribution of aphyllophoroid fungi (Basidiomycota) in Finland Kunttu P1, Kulju M2, Kekki T3, Pennanen J4, Savola K5, Helo T6 and Kotiranta H7 1University of Eastern Finland, School of Forest Sciences, P.O. Box 111, FI-80101 Joensuu, Finland 2Biodiversity Unit P.O. Box 3000, FI-90014 University of Oulu, Finland 3Jyväskylä University Museum, Natural History Section, P.O. BOX 35, FI-40014 University of Jyväskylä, Finland 4Pentbyntie 1 A 2, FI-10300 Karjaa, Finland 5The Finnish Association for Nature Conservation, Itälahdenkatu 22 b A, FI-00210 Helsinki, Finland 6Erätie 13 C 19, FI-87200 Kajaani, Finland 7Finnish Environment Institute, P.O. Box 140, FI-00251 Helsinki, Finland Kunttu P, Kulju M, Kekki T, Pennanen J, Savola K, Helo T, Kotiranta H 2016 – Extensions of known geographic distribution of aphyllophoroid fungi (Basidiomycota) in Finland. Mycosphere 7(3), 333–357, Doi 10.5943/mycosphere/7/3/7 Abstract This article contributes the knowledge of Finnish aphyllophoroid funga with nationally or regionally new species, and records of rare species. Ceriporia bresadolae, Clavaria tenuipes and Renatobasidium notabile are presented as new aphyllophoroid species to Finland. Ceriporia bresadolae and R. notabile are globally rare species. The records of Ceriporia aurantiocarnescens, Crustomyces subabruptus, Sistotrema autumnale, Trechispora elongata, and Trechispora silvae- ryae are the second in Finland. New records (or localities) are provided for 33 species with no more than 10 records in Finland. In addition, 76 records of aphyllophoroid species are reported as new to some subzones of the boreal vegetation zone in Finland. -

A Phylogenetic Overview of the Antrodia Clade (Basidiomycota, Polyporales)

Mycologia, 105(6), 2013, pp. 1391–1411. DOI: 10.3852/13-051 # 2013 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 A phylogenetic overview of the antrodia clade (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) Beatriz Ortiz-Santana1 phylogenetic studies also have recognized the genera Daniel L. Lindner Amylocystis, Dacryobolus, Melanoporia, Pycnoporellus, US Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Center for Sarcoporia and Wolfiporia as part of the antrodia clade Forest Mycology Research, One Gifford Pinchot Drive, (SY Kim and Jung 2000, 2001; Binder and Hibbett Madison, Wisconsin 53726 2002; Hibbett and Binder 2002; SY Kim et al. 2003; Otto Miettinen Binder et al. 2005), while the genera Antrodia, Botanical Museum, University of Helsinki, PO Box 7, Daedalea, Fomitopsis, Laetiporus and Sparassis have 00014, Helsinki, Finland received attention in regard to species delimitation (SY Kim et al. 2001, 2003; KM Kim et al. 2005, 2007; Alfredo Justo Desjardin et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2004; David S. Hibbett Dai et al. 2006; Blanco-Dios et al. 2006; Chiu 2007; Clark University, Biology Department, 950 Main Street, Worcester, Massachusetts 01610 Lindner and Banik 2008; Yu et al. 2010; Banik et al. 2010, 2012; Garcia-Sandoval et al. 2011; Lindner et al. 2011; Rajchenberg et al. 2011; Zhou and Wei 2012; Abstract: Phylogenetic relationships among mem- Bernicchia et al. 2012; Spirin et al. 2012, 2013). These bers of the antrodia clade were investigated with studies also established that some of the genera are molecular data from two nuclear ribosomal DNA not monophyletic and several modifications have regions, LSU and ITS. A total of 123 species been proposed: the segregation of Antrodia s.l. -

Download Download

LITERATURE UPDATE FOR TEXAS FLESHY BASIDIOMYCOTA WITH NEW VOUCHERED RECORDS FOR SOUTHEAST TEXAS David P. Lewis Clark L. Ovrebo N. Jay Justice 262 CR 3062 Department of Biology 16055 Michelle Drive Newton, Texas 75966, U.S.A. University of Central Oklahoma Alexander, Arkansas 72002, U.S.A. [email protected] Edmond, Oklahoma 73034, U.S.A. [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT This is a second paper documenting the literature records for Texas fleshy basidiomycetous fungi and includes both older literature and recently published papers. We report 80 literature articles which include 14 new taxa described from Texas. We also report on 120 new records of fleshy basdiomycetous fungi collected primarily from southeast Texas. RESUMEN Este es un segundo artículo que documenta el registro de nuevas especies de hongos carnosos basidiomicetos, incluyendo artículos antiguos y recientes. Reportamos 80 artículos científicamente relacionados con estas especies que incluyen 14 taxones con holotipos en Texas. Así mismo, reportamos unos 120 nuevos registros de hongos carnosos basidiomicetos recolectados primordialmente en al sureste de Texas. PART I—MYCOLOGICAL LITERATURE ON TEXAS FLESHY BASIDIOMYCOTA Lewis and Ovrebo (2009) previously reported on literature for Texas fleshy Basidiomycota and also listed new vouchered records for Texas of that group. Presented here is an update to the listing which includes literature published since 2009 and also includes older references that we previously had not uncovered. The authors’ primary research interests center around gilled mushrooms and boletes so perhaps the list that follows is most complete for the fungi of these groups. We have, however, attempted to locate references for all fleshy basidio- mycetous fungi. -

Hymenomycetes from Multan District

Pak. J. Bot., 39(2): 651-657, 2007. HYMENOMYCETES FROM MULTAN DISTRICT KISHWAR SULTANA, MISBAH GUL*, SYEDA SIDDIQA FIRDOUS* AND REHANA ASGHAR* Pakistan Museum of Natural History, Garden Avenue, Shakarparian, Islamabad, Pakistan. *Department of Botany, University of Arid Agriculture, Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Author for correspondence. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Twenty samples of mushroom and toadstools (Hymenomycetes) were collected from Multan district during July-October 2003. Twelve species belonging to 8 genera of class Basidiomycetes were recorded for the 1st time from Multan: Albatrellus caeruleoporus (Peck.) Pauzar, Agaricus arvensis Sch., Agaricus semotus Fr., Agaricus silvaticus Schaef., Coprinus comatus (Muell. ex. Fr.), S.F. Gray, Hypholoma marginatum (Pers.) Schroet., Hypholoma radicosum Lange., Marasmiellus omphaloides (Berk.) Singer, Panaeolus fimicola (Pers. ex. Fr.) Quel., Psathyrella candolleana (Fr.) Maire, Psathyrella artemisiae (Pass.) K. M. and Podaxis pistilaris (L. ex. Pers.) Fr. Seven of these species are edible or of medicinal value. Introduction Multan lies between north latitude 29’-22’ and 30’-45’ and east longitude 71’-4’ and 72’ 4’55. It is located in a bend created by five confluent rivers. It is about 215 meters (740 feet) above sea level. The mean rainfall of the area surveyed is 125mm in the Southwest and 150 mm in the Northeast. The hottest months are May and June with the mean temperature ranging from 107°F to 109°F, while mean temperature of Multan from July to October is 104°F. The mean rainfall from July to October is 18 mm. The soils are moderately calcareous with pH ranging from 8.2 to 8.4. -

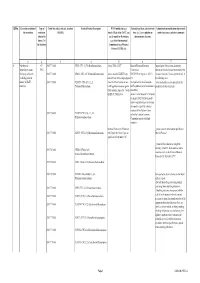

Phylum Order Number of Species Number of Orders Family Genus Species Japanese Name Properties Phytopathogenicity Date Pref

Phylum Order Number of species Number of orders family genus species Japanese name properties phytopathogenicity date Pref. points R inhibition H inhibition R SD H SD Basidiomycota Polyporales 98 12 Meruliaceae Abortiporus Abortiporus biennis ニクウチワタケ saprobic "+" 2004-07-18 Kumamoto Haru, Kikuchi 40.4 -1.6 7.6 3.2 Basidiomycota Agaricales 171 1 Meruliaceae Abortiporus Abortiporus biennis ニクウチワタケ saprobic "+" 2004-07-16 Hokkaido Shari, Shari 74 39.3 2.8 4.3 Basidiomycota Agaricales 269 1 Agaricaceae Agaricus Agaricus arvensis シロオオハラタケ saprobic "-" 2000-09-25 Gunma Kawaba, Tone 87 49.1 2.4 2.3 Basidiomycota Polyporales 181 12 Agaricaceae Agaricus Agaricus bisporus ツクリタケ saprobic "-" 2004-04-16 Gunma Horosawa, Kiryu 36.2 -23 3.6 1.4 Basidiomycota Hymenochaetales 129 8 Agaricaceae Agaricus Agaricus moelleri ナカグロモリノカサ saprobic "-" 2003-07-15 Gunma Hirai, Kiryu 64.4 44.4 9.6 4.4 Basidiomycota Polyporales 105 12 Agaricaceae Agaricus Agaricus moelleri ナカグロモリノカサ saprobic "-" 2003-06-26 Nagano Minamiminowa, Kamiina 70.1 3.7 2.5 5.3 Basidiomycota Auriculariales 37 2 Agaricaceae Agaricus Agaricus subrutilescens ザラエノハラタケ saprobic "-" 2001-08-20 Fukushima Showa 67.9 37.8 0.6 0.6 Basidiomycota Boletales 251 3 Agaricaceae Agaricus Agaricus subrutilescens ザラエノハラタケ saprobic "-" 2000-09-25 Yamanashi Hakusyu, Hokuto 80.7 48.3 3.7 7.4 Basidiomycota Agaricales 9 1 Agaricaceae Agaricus Agaricus subrutilescens ザラエノハラタケ saprobic "-" 85.9 68.1 1.9 3.1 Basidiomycota Hymenochaetales 129 8 Strophariaceae Agrocybe Agrocybe cylindracea ヤナギマツタケ saprobic "-" 2003-08-23 -

A Note on Battarrea Phalloides in Turkey

MANTAR DERGİSİ/The Journal of Fungus Nisan(2021)12(1)1-9 Geliş(Recevied) :26.09.2020 Research Article Kabul(Accepted) :12.11.2020 Doi: 10.30708.mantar.800585 A Note on Battarrea phalloides in Turkey 1*, 2 1 Ilgaz AKATA Deniz ALTUNTAŞ , Ergin ŞAHİN , Hakan ALLI3, ŞANLI KABAKTEPE4 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Ankara University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Ankara, Turkey Orcid ID: 0000-0002-1731-1302/ [email protected] Orcid ID: 0000-0003-1711-738X/ [email protected] 2Ankara University, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Ankara, Turkey Orcid ID: 0000-0003-0142-6188/ [email protected] 3Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, Muğla, Turkey Orcid ID: 0000-0001-8781-7089/ [email protected] 4Malatya Turgut Ozal University, Battalgazi Vocat Sch., Battalgazi, Malatya, Turkey Orcid ID: 0000-0001-8286-9225/[email protected] Abstract: The current study was conducted based on a Battarrea sample obtained from Muğla province (Turkey). The sample was identified based on both conventional methods and ITS rDNA region-based molecular phylogeny. By taking into account the high sequence similarity between the sample (ANK Akata & Altuntaş 690) and Battarrea phalloides the relevant specimen was considered to be B. Phalloides and the morphological data also strengthen this finding. In this study, photos of macro and microscopic structures, a short description, scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of spores and elaters, and the ITS rDNA region-based molecular phylogeny of the samples were given. Also, the distribution of B. phalloides specimens identified thus far from Turkey was revealed for the first time in this study. -

Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area

Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area • Giuseppe Venturella Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Edited by Giuseppe Venturella Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Diversity www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Editor Giuseppe Venturella MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Giuseppe Venturella University of Palermo Italy Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Diversity (ISSN 1424-2818) (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/diversity/special issues/ fungal diversity). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03936-978-2 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03936-979-9 (PDF) c 2020 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Giuseppe Venturella Fungal Diversity in the Mediterranean Area Reprinted from: Diversity 2020, 12, 253, doi:10.3390/d12060253 .................... 1 Elias Polemis, Vassiliki Fryssouli, Vassileios Daskalopoulos and Georgios I.