Fully Halogenated Chlorofluorocarbons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7, Haloalkanes, Properties and Substitution Reactions of Haloalkanes Table of Contents 1

Chapter 7, Haloalkanes, Properties and Substitution Reactions of Haloalkanes Table of Contents 1. Alkyl Halides (Haloalkane) 2. Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions (SNX, X=1 or 2) 3. Nucleophiles (Acid-Base Chemistry, pka) 4. Leaving Groups (Acid-Base Chemistry, pka) 5. Kinetics of a Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction: An SN2 Reaction 6. A Mechanism for the SN2 Reaction 7. The Stereochemistry of SN2 Reactions 8. A Mechanism for the SN1 Reaction 9. Carbocations, SN1, E1 10. Stereochemistry of SN1 Reactions 11. Factors Affecting the Rates of SN1 and SN2 Reactions 12. --Eliminations, E1 and E2 13. E2 and E1 mechanisms and product predictions In this chapter we will consider: What groups can be replaced (i.e., substituted) or eliminated The various mechanisms by which such processes occur The conditions that can promote such reactions Alkyl Halides (Haloalkane) An alkyl halide has a halogen atom bonded to an sp3-hybridized (tetrahedral) carbon atom The carbon–chlorine and carbon– bromine bonds are polarized because the halogen is more electronegative than carbon The carbon-iodine bond do not have a per- manent dipole, the bond is easily polarizable Iodine is a good leaving group due to its polarizability, i.e. its ability to stabilize a charge due to its large atomic size Generally, a carbon-halogen bond is polar with a partial positive () charge on the carbon and partial negative () charge on the halogen C X X = Cl, Br, I Different Types of Organic Halides Alkyl halides (haloalkanes) sp3-hybridized Attached to Attached to Attached -

Classifying Halogenoalkanes Reactions Of

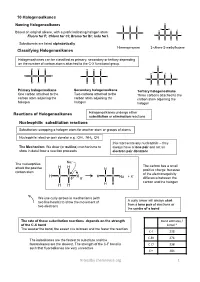

10 Halogenoalkanes H Naming Halogenoalkanes H H H H C H H H H Based on original alkane, with a prefix indicating halogen atom: H C C C H Fluoro for F; Chloro for Cl; Bromo for Br; Iodo for I. H C C C C H Br H H H Cl H H Substituents are listed alphabetically 1-bromopropane 2-chloro-2-methylbutane Classifying Halogenoalkanes Halogenoalkanes can be classified as primary, secondary or tertiary depending on the number of carbon atoms attached to the C-X functional group. H H H H H H H H C H H H H H C C C H H C C C H H C C C C H Br H H H Br H H Cl H H Primary halogenoalkane Secondary halogenoalkane Tertiary halogenoalkane One carbon attached to the Two carbons attached to the Three carbons attached to the carbon atom adjoining the carbon atom adjoining the carbon atom adjoining the halogen halogen halogen Reactions of Halogenoalkanes Halogenoalkanes undergo either substitution or elimination reactions Nucleophilic substitution reactions Substitution: swapping a halogen atom for another atom or groups of atoms - - Nucleophile: electron pair donator e.g. :OH , :NH3, CN :Nu represents any nucleophile – they The Mechanism: We draw (or outline) mechanisms to always have a lone pair and act as show in detail how a reaction proceeds electron pair donators Nu:- The nucleophiles The carbon has a small attack the positive H H H H positive charge because carbon atom of the electronegativity H C C X H C C + X- δ+ δ- Nu difference between the carbon and the halogen H H H H We use curly arrows in mechanisms (with A curly arrow will always two line heads) to show the movement of start from a of electrons or two electrons lone pair the centre of a bond The rate of these substitution reactions depends on the strength Bond enthalpy / of the C-X bond kJmol-1 The weaker the bond, the easier it is to break and the faster the reaction. -

Generic Functional Group Pattern in Ordero of Nomenclature Priority in Our Course. Specific Example Using Suffix (2D and 3D)

Generic Functional Group Pattern Specific Example Specific Example in ordero of nomenclature priority Using Suffix (2D and 3D) Using Prefix when in our course. when highest priority FG lower priority FG 1. carboxylic acid (2D) carboxylic acid (3D) O Condensed line formula IUPAC: ethanoic acid O H H prefix example C H common: acetic acid RCO2H or HO2CR C C R O #-carboxy H O RCH(CO H)R' H suffix: -oic acid 2 O not used in our course FG on FG on C H (acids are the highest priority prefix: #-carboxy the right the left H3C O group that we use) FG in the carbonyl resonance (2D) middle (C=O) is possible 2. anhydride (2D) Condensed line formula anhydride (3D) IUPAC: ethanoic propanoic anhydride O O RCO2COR' or ROCO2CR' H H O O H C C C CH C 3 R O R H3C O C H H 2 prefix example H O C H suffix: -oic -oic anhydride (2D) (just one -oic anhydride, O O O C C O if symmetrical) 3 1 H 4 H 2 prefix: #-acyloxyalkanecarbonyl O O OH (prefix not required for us) carbonyl resonance 4-acyloxymethanebutanoic acid (C=O) is possible (prefix not required for us - too difficult) 3. ester (2D) alkyl name (goes in front as separate word) ester (3D) H H H IUPAC: propyl ethanoate O C Condensed line formula C O C common: propyl acetate C R' H H R O RCO2R' or R'O2CR H H C C H O H H2 RCH(CO2CH3)R' prefix: alkyl suffix: -oate H C C CH3 O H C O C prefix example 3 H prefix: #-alkoxycarbonyl 2 O O (2D) 3 1 carbonyl resonance 4 2 (C=O) is possible O OH 4-methoxycarbonylbutanoic acid 4. -

A Perovskite-Based Paper Microfluidic Sensor for Haloalkane Assays

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 26 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.682006 A Perovskite-Based Paper Microfluidic Sensor for Haloalkane Assays Lili Xie 1, Jie Zan 1, Zhijian Yang 1, Qinxia Wu 1, Xiaofeng Chen 1, Xiangyu Ou 1, Caihou Lin 2*, Qiushui Chen 1,3* and Huanghao Yang 1,3* 1 Ministry of Education (MOE) Key Laboratory for Analytical Science of Food Safety and Biology, Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Analysis and Detection Technology for Food Safety, College of Chemistry, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou, China, 2 Department of Neurosurgery, Fujian Medical University Union Hospital, Fuzhou, China, 3 Fujian Science and Technology Innovation Laboratory for Optoelectronic Information of China, Fuzhou, China Detection of haloalkanes is of great industrial and scientific importance because some Edited by: haloalkanes are found serious biological and atmospheric issues. The development Jinyi Lin, of a flexible, wearable sensing device for haloalkane assays is highly desired. Here, Nanjing Tech University, China we develop a paper-based microfluidic sensor to achieve low-cost, high-throughput, Reviewed by: Xiaobao Xu, and convenient detection of haloalkanes using perovskite nanocrystals as a nanoprobe Nanjing University of Science and through anion exchanging. We demonstrate that the CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, or I) Technology, China nanocrystals are selectively and sensitively in response to haloalkanes (CH2Cl2, CH2Br2), Xuewen Wang, Northwestern Polytechnical and their concentrations can be determined as a function of photoluminescence University, China spectral shifts of perovskite nanocrystals. In particular, an addition of nucleophilic trialkyl *Correspondence: phosphines (TOP) or a UV-photon-induced electron transfer from CsPbX3 nanocrystals is Caihou Lin [email protected] responsible for achieving fast sensing of haloalkanes. -

Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes

05 Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes Polyethylene is the most widely used plastic, making up items such as packing foam, plastic bottles, and plastic utensils (top: © Jon Larson/iStockphoto; middle: GNL Media/Digital Vision/Getty Images, Inc.; bottom: © Lakhesis/iStockphoto). Inset: A model of ethylene. KEY QUESTIONS 5.1 What Are the Characteristic Reactions of Alkenes? 5.8 How Can Alkynes Be Reduced to Alkenes and 5.2 What Is a Reaction Mechanism? Alkanes? 5.3 What Are the Mechanisms of Electrophilic Additions HOW TO to Alkenes? 5.1 How to Draw Mechanisms 5.4 What Are Carbocation Rearrangements? 5.5 What Is Hydroboration–Oxidation of an Alkene? CHEMICAL CONNECTIONS 5.6 How Can an Alkene Be Reduced to an Alkane? 5A Catalytic Cracking and the Importance of Alkenes 5.7 How Can an Acetylide Anion Be Used to Create a New Carbon–Carbon Bond? IN THIS CHAPTER, we begin our systematic study of organic reactions and their mecha- nisms. Reaction mechanisms are step-by-step descriptions of how reactions proceed and are one of the most important unifying concepts in organic chemistry. We use the reactions of alkenes as the vehicle to introduce this concept. 129 130 CHAPTER 5 Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes 5.1 What Are the Characteristic Reactions of Alkenes? The most characteristic reaction of alkenes is addition to the carbon–carbon double bond in such a way that the pi bond is broken and, in its place, sigma bonds are formed to two new atoms or groups of atoms. Several examples of reactions at the carbon–carbon double bond are shown in Table 5.1, along with the descriptive name(s) associated with each. -

In This Handout, All of Our Functional Groups Are Presented As Condensed Line Formulas, 2D and 3D Formulas and with Nomenclature Prefixes and Suffixes (If Present)

In this handout, all of our functional groups are presented as condensed line formulas, 2D and 3D formulas and with nomenclature prefixes and suffixes (if present). Organic names are built on a foundation of alkanes, alkenes and alkynes. Those examples are presented first and you need to know those rules. The strategies can be found in Chapter 4 of our textbook (alkanes: pages 93-98, cycloalkanes 102-104, alkenes: pages 104-110, alkynes: pages 112-113 and combinations of all of them 113-115). After introducing examples of alkanes, alkenes, alkynes and combinations of them, the functional groups are presented in order of priority. A few nomenclature examples are provided for each of the functional groups. Examples of the various functional groups are presented on pages 115-135 in the textbook. Two overview pages are on pages 136-137. Some functional groups have a suffix name when they are the highest priority functional group and a prefix name when they are not the highest priority group, and these are added to the skeletal names with identifying numbers and stereochemistry terms (E and Z for alkenes, R and S for chiral centers and cis and trans for rings). Several low priority functional groups only have a prefix name. A few additional special patterns are shown on pages 98-102. The only way to learn this topic is practice (over and over). The best practice approach is to actually write out the names (on an extra piece of paper or on a white board, and then do it again). The same functional groups are used throughout the entire course. -

Haloalkanes, Alcohols and Amines. Year 1 Dr

Haloalkanes, Alcohols and Amines. Year 1 Dr. Chris Braddock [[email protected], Rm 440]: 10 lectures Aims of course: To introduce the functional group chemistry of haloalkanes, alcohols and amines, building on the functional group approach of Dr Smith's course where alkanes, alkenes, alkynes and benzene were discussed. Course objectives: At the end of this course you should be able to: • Identify correctly the various functional groups and reagents introduced on this course; • Recognise characteristic IR and NMR signals in their spectra; • Predict the product of a reaction involving an haloalkane, alcohol or amine with a given reagent; • Select reagents for the common transformations of haloalkanes, alcohols and amines into other functionalities; • Select reagents for the preparation of haloalkanes, alcohols and amines from other substrates; • Explain the mechanistic rationale underpinning the above. Recommended Texts Vollhardt and Schore, Organic Chemistry, 3rd edition, WH Freeman & Co, New York, 1999. Sykes A Primer to Mechanism in Organic Chemistry Longman, Harlow, 1995 Clayden, Greeves, Warren and Wothers Organic Chemistry OUP, Oxford 2001. Course Content A. Haloalkane Group Chemistry (Alkyl Halides) (a) Structure and Physical Properties: nomenclature; physical properties; spectroscopic properties. β (b) Haloalkane group reactivity: Nucleophilic substitution S N1 and SN2; - elimination; metal-halogen exchange. (c) Synthesis of haloalkanes: electrophilic addition to alkenes; radical addition to alkenes; from alcohols. B. Hydroxyl Group Chemistry (Alcohols) (a) Structure and Physical Properties: Structure; H-bonding; spectroscopic properties . (b) Alcohol group reactivity: Hydroxyl group acidity; Nucleophilic reactions of hydroxyl groups without C-O cleavage; nucleophilic reactions of hydroxyl groups which convert the OH into a good leaving group; nucleophilic reactions of hydroxyl groups which place a good leaving group on oxygen. -

Haloalkanes and Haloarenes

1010Unit Objectives HaloalkanesHaloalkanes andand After studying this Unit, you will be able to HaloarHaloarHaloarHaloarenesenesenesenesenesenes • name haloalkanes and haloarenes according to the IUPAC system of nomenclature from their given structures; Halogenated compounds persist in the environment due to their • describe the reactions involved in resistance to breakdown by soil bacteria. the preparation of haloalkanes and haloarenes and understand various reactions that they The replacement of hydrogen atom(s) in an aliphatic undergo; or aromatic hydrocarbon by halogen atom(s) results • correlate the structures of in the formation of alkyl halide (haloalkane) and aryl haloalkanes and haloarenes with halide (haloarene), respectively. Haloalkanes contain various types of reactions; halogen atom(s) attached to the sp3 hybridised carbon • use stereochemistry as a tool for atom of an alkyl group whereas haloarenes contain understanding the reaction halogen atom(s) attached to sp2 hybridised carbon mechanism; atom(s) of an aryl group. Many halogen containing • appreciate the applications of organic compounds occur in nature and some of organo-metallic compounds; these are clinically useful. These classes of compounds • highlight the environmental effects of polyhalogen compounds. find wide applications in industry as well as in day- to-day life. They are used as solvents for relatively non-polar compounds and as starting materials for the synthesis of wide range of organic compounds. Chlorine containing antibiotic, chloramphenicol, produced by microorganisms is very effective for the treatment of typhoid fever. Our body produces iodine containing hormone, thyroxine, the deficiency of which causes a disease called goiter. Synthetic halogen compounds, viz. chloroquine is used for the treatment of malaria; halothane is used as an anaesthetic during surgery. -

Survey of Key Functional Groups Overview Overview Overview

11/2/2009 Overview Survey of Key Functional Groups Ch 8.1 Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 Overview Overview Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 1 11/2/2009 Concerns Functional Group Names Getting overwhelmed Alcohol Strange new formulas Strange new names Strange new reagents Alkyl halide, Haloalkane Many new relationships leads to brain meltdown !!! Info builds ONE step at a Thiol time Ch 8 surveys FG Names, drawings, properties No new reactions (almost) Ether Sulfide Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 RX Names Common or Substitutive (IUPAC)? Special Compounds Use Common Names Alkyl halide Haloalkane Haloforms Alkyl group attached Halogen substitutent methylene chloride to Halogen attached to Alkane chloroform ()(dichloromethane) bromoform Methyl chloride Chloromethane iodoform Ethyl bromide Bromoethane Useful solvents Special compounds carbon tetrachloride - hydrophobic Special groups - moderately polar carbon tetrabromide - volatile methylene, allyl, vinyl, benzyl but all linked to health problems Special history allyl bromide these slides will be posted Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 2 11/2/2009 Give “haloalkane” (IUPAC) names Give “haloalkane” (IUPAC) names 2- fluoropropane cis-121,2-dibromocyc lo hexane Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 Chem 201 – Functional Group Survey 11/2/2009 ROR’ Names ROR’ Names Common & Substitutive -

91165 Organic Chemistry Cornell Notes

No Brain Too Small CHEMISTRY AS91165 Introduction to Organic Chemistry What are Contain hydrogen and carbon atoms only hydrocarbons? Influence reactivity – give similar chemical and physical properties What are the • alkanes C-C functional groups • alkenes C=C to know at level • alkynes C≡ C 2? • haloalkanes R-X (where X is F, Cl, Br, I) • alcohols R-OH • carboxylic acids R-COOH • amines R-NH2 R is rest of molecule # of C atoms in the molecule. 1 meth- 2 eth- 3 prop- 4 but- What are the 5 pent- 6 hex - 7 hept- 8 oct- prefixes for C 1- 8? CnH2n+2 Each C atom bonded to 4 other atoms; no spare bOnds within What is the molecule for further atoms to be added, contain only C-C single general formula bonds; this is called a saturated molecule for alkanes and what are they saturated hydrocarbons? SUMMARY: Organic chemistry is study of compounds containing carbon. Homologous series have fixed functional groups which give the compound its characteristic properties. Alkanes are saturated hydrocarbons having single bonds between carbon atoms. No Brain Too Small CHEMISTRY AS91165 Types of Formula What does the Identifies the number and type of atoms molecular formula e.g. C5H12 tell you? What does the Shows how the atoms are arranged and bonded to each other structural formula show you? How do we write a structural or CH3CH2CH2CH2CH3 or formula as a even CH3(CH2)3CH3 condensed structural formula? or CH3CH(CH3)CH2CH3 SUMMARY: We can write the formulae of organic molecules in a number of different ways; molecular, structural and condensed structural formula. -

Alkyl Halides

3/12/2012 Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Alkyl halides Alkyl halides Alkyl: Halogen, X, is directly bonded to sp3 carbon A compound with a halogen atom bonded to one of the sp3 hybrid carbon atoms of an alkyl group + - C X 1 2 Nomenclature of Alkyl halides Substitutive nomenclature • Substitutive nomenclature of alkyl halides • functional class nomenclature treats the halogen as a halo- ( fluoro-, chloro-, – The alkyl group and the halide ( fluoride, chloride, bromo-, or iodo-) substituent on an alkane bromide, or iodide) are designated as separate chain. words. – The alkyl group is named on the basis of its • The carbon chain is numbered in the direction longest continuous chain beginning at the carbon that gives the substituted carbon the lower to which the halogen is attached. locant. Cl Cl Br H3C I Br CH I 3 1-Bromo-butane Iodomethane Chloro-cyclopentane n-Butyl bromide Methyl iodide Cyclopentyl Chloride 3 4 n-Butyl bromide Methyl iodide Cyclopentyl Chloride 1 3/12/2012 Naming Alkyl Halides using Substitutive nomenclature Substitutive Nomenclature • When the carbon chain bears both a halogen • Find longest chain, name it as parent chain and an alkyl substituent, the two substituents – (Contains double or triple bond if present) are considered of equal rank, and the chain is – Number from end nearest any substituent (alkyl or numbered so as to give the lower number to halogen) the substituent nearer the end of the chain. • Substitutive names are preferred, but functional class names are sometimes more convenient or more familiar and -

Chapter 7: Haloalkanes

188 Chapter 7: Haloalkanes Chapter 7: Haloalkanes Problems 7.1 Write the IUPAC name for each compound: CH3 (a) (b) Br Cl 1-chloro-3-methyl-2-butene 1-bromo-1-methylcyclohexane Cl Cl (c) (d) CH3CHCH2Cl 1,2-dichloropropane 2-chloro-1,3-butadiene 7.2 Determine whether the following haloalkanes underwent substitution, elimination, or both substitution and elimination: O (a) KOCCH Br 3 O +KBr CH3COOH O In this reaction, the haloalkane underwent substitution. The bromine group was replaced by an acetate (CH3COO−) group. NaOCH CH (b) 2 3 + +NaCl CH3CH2OH Cl OCH2CH3 In this reaction, the haloalkane underwent both substitution and elimination. In the substitution, the chlorine group was replaced by an ethoxy (CH3CH2O−) group. Chapter 7: Haloalkanes 189 7.3 Complete these nucleophilic substitution reactions: (a) – + + – Br +CH3CH2S Na SCH2CH3 +NaBr O O (b) – + + – Br + CH3CO Na OCCH3 +NaBr 7.4 Answer the following questions: (a) Potassium cyanide, KCN, reacts faster than trimethylamine, (CH3)3N, with 1-chloropentane. What type of substitution mechanism does this haloalkane likely undergo? The rate of this reaction is influenced by the strength of the nucleophile, suggesting that the mechanism of substitution is SN2. The cyanide ion is a much better nucleophile than an amine. (b) Compound A reacts faster with dimethylamine, (CH3)2NH, than compound B.What does this reveal about the relative ability of each haloalkane to undergo SN2? SN1? Br Br A B Compound A is more able to undergo SN2, which involves backside attack by the nucleophile, because it is sterically less hindered than B. Both compounds A and B have about the same reactivity towards SN1, because both A and B can ionize to give carbocations of comparable stability.