Addressing International Reputation Through the Arts!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Amalia Damgaard

By Private Chef Amalia Damgaard CHILEAN PANORAMA Although it appears slim and small, Chile is a long and narrow country about the size of Texas, with a vast coast line covering about 3,998 miles. The Pacific Ocean borders to the west; Argentina is a neighbor to the east; Bolivia, to the northeast; and Peru, to the north. Because of its geographical location, Chile has an unusual and fun landscape, with deserts, beaches, fjords, glaciers and icebergs, fertile lands, the Andes mountains, over 600 volcanoes (some active), and sub-artic conditions in the South. Since Chile is below the equator, their seasons are different from ours in the United States. So, when we have winter they have summer, and so on. Even though Chile had years of political and economic turmoil, it has evolved into a market-oriented economy with strong foreign trade. Currently, it has the strongest economy in South America, with a relatively-low crime rate, and a high standard of living. Chile is a land rich in beauty, culture, and literature. It is called “the Switzerland of South America” because of its natural splendor. World renowned poets, Pablo Neruda and Gabriela Mistral, won Nobel Prizes. The majority of Chileans are descendants of Europeans, namely Spanish, French, and German, and others in smaller numbers. Allegedly, the original inhabitants of the region prior to Spanish conquest were not natives but merely nomads who lived in the area. Their descendants are today about 3% of the population. A mixture of the so-called natives and European settlers is called “mestizo.” Today’s mestizos are so well blended that they look mostly European. -

Periférica 2020 320-330.Pdf

/ AUTORA / CORREO-E María Paulina Soto Labbé. [email protected] / ADSCRIPCIÓN PROFESIONAL Doctora en la Universidad de las Artes de Ecuador. / TÍTULO FONDART: Balance político de un instrumento de fi nanciamiento cultural del Chile 1990-2010. / RESUMEN Analizamos tendencias internacionales de fi nanciación instrumento de fi nanciación analizado; y establecemos una sectorial; cuestionamos el carácter de política pública del relación entre el principio político-ideológico neoliberal Sub- instrumento Fondo Nacional de las Artes y la Cultura FON- sidiariedad y el crecimiento asimétrico que esta genera. El DART; evaluamos la relación crecimiento y profesionaliza- presente artículo es resultado de una investigación realizada ción sectorial respecto del aumento de exigencias sobre el en el año 2011. / PALABRAS CLAVE Financiamiento de la cultura; fondos concursables de cultura; subsidio en cultura. / Artículo recibido: 20/10/2020 / Artículo aceptado: 03/11/2020 / AUTHOR / E-MAIL María Paulina Soto Labbé. [email protected] / PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATION Doctor at the University of the Arts of Ecuador. / TITLE FONDART: Political balance of a cultural fi nancing instrument in Chile 1990-2010 . / ABSTRACT We analyze international trends in sector fi nancing; We in demands on the fi nancing instrument analyzed; and we question the character of public policy of the instrument establish a relationship between the neoliberal political- National Fund for Arts and Culture of Chile FONDART; ideological principle Subsidiarity and the asymmetric growth We evaluate the relationship between growth and that it generates. This article is the result of an investigation professionalization in the sector and its eff ects on the increase carried out in 2011. / KEYWORDS Financing of culture; competitive culture funds; subsidy in culture. -

List of Acronyms

LIST OF ACRONYMS A______________________________ 20. ANARCICH: NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF COMMUNITY RADIOS 1. AP: PACIFIC ALLIANCE. AND CITIZENS OF CHILE. 2. ATN: SOCIETY OF AUDIOVISUAL 21. ARCHITECTURE OF CHILE: DIRECTORS, SCRIPTWRITERS AND SECTORAL BRAND OF THE DRAMATURGS. ARCHITECTURE SECTOR IN CHILE. 3. ACHS: CHILEAN SECURITY B______________________________ ASSOCIATION. 22. BAFONA: NATIONAL FOLK BALLET. 4. APCT: ASSOCIATION OF PRODUCERS AND FILM AND 23. BID: INTER-AMERICAN TELEVISION. DEVELOPMENT BANK. 5. AOA: ASSOCIATION OF OFFICES OF 24. BAJ: BALMACEDA ARTE JOVEN. ARCHITECTS OF CHILE. 25. BIPS: INTEGRATED BANK OF 6. APEC: ASIA PACIFIC ECONOMIC SOCIAL PROJECTS. COOPERATION FORUM. C______________________________ 7. AIC: ASSOCIATION OF ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS OF CHILE 26. CNTV: NATIONAL TELEVISION A.G. COUNCIL. 8. ACHAP: CHILEAN PUBLICITY 27. CHEC: CHILE CREATIVE ECONOMY. ASSOCIATION. 28. CPTPP: COMPREHENSIVE AND 9. ACTI: CHILEAN ASSOCIATION OF PROGRESSIVE AGREEMENT FOR INFORMATION TECHNOLOGIES TRANS-PACIFIC PARTNERSHIP. COMPANIES A.G. 29. CHILEACTORS: CORPORATION OF 10. ADOC: DOCUMENTARY ACTORS AND ACTRESSES OF CHILE. ASSOCIATION OF CHILE. 30. CORTECH: THEATER 11. ANIMACHI: CHILEAN ANIMATION CORPORATION OF CHILE. ASSOCIATION. 31. CRIN: CENTER FOR INTEGRATED 12. API CHILE: ASSOCIATION OF NATIONAL RECORDS. INDEPENDENT PRODUCERS OF CHILE. 32. UNESCO CONVENTION, 2005: 13. ADG: ASSOCIATION OF CONVENTION ON THE PROTECTION DIRECTORS AND SCRIPTWRITERS OF AND PROMOTION OF THE DIVERSITY CHILE. OF CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS. 14. ADTRES: GROUP OF DESIGNERS, 33. CNCA: NATIONAL COUNCIL OF TECHNICIANS AND SCENIC CULTURE AND ARTS. PRODUCERS. 34. CCHC: CHILEAN CHAMBER OF 15. APECH: ASSOCIATION OF CONSTRUCTION, A.G. PAINTERS AND SCULPTORS OF CHILE. 35. CCS: SANTIAGO CHAMBER OF 16. ANATEL: NATIONAL TELEVISION COMMERCE. ASSOCIATION OF CHILE. 36. CORFO: PRODUCTION 17. ACA: ASSOCIATED DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION. -

Open Master Thesis Carolyn Henzi.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF GOVERNMENT-SPONSORED INTERGENERATIONAL PROGRAMS AND PRACTICES IN CHILE A Thesis in Agricultural and Extension Education by Carolyn Mariel Henzi Plaza © 2020 Carolyn Mariel Henzi Plaza Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science December 2020 The thesis of Carolyn Mariel Henzi Plaza was reviewed and approved by the following: Matthew Kaplan Professor of Agricultural and Extension Education Intergenerational Programs and Aging, College of Agricultural Sciences. Thesis Advisor Nicole Webster Associate Professor of Youth and International Development and African Studies. Director of the 2iE-Penn State Centre for Collaborative Engagement in Burkina Faso, West Africa. Comparative and International Education Faculty (CIED), College of Education John Holst Associate Professor of Education, College of Education Mark Brennan Professor and UNESCO Chair in Community, Leadership, and Youth Development Director of Graduate Studies, Agricultural and Extension Education and Applied Youth, Family, and Community Education iii ABSTRACT The 21st century faces sociodemographic, educational, and economic challenges associated with the global increase in older adult populations and a decrease in the number of children. National and international organizations have called for spaces for all ages, with more age-inclusive policies and support services. Here, the concept of intergenerational (IG) solidarity is seen as a crucial element in the development and wellbeing of all generations (Stuckelberger & Vikat, 2007; WHO, 2007). Chile is not exempt from this call for paying increased attention to the needs of the young and the old. During the last few decades, public policies and programs have been developed to protect and provide opportunities for both older adults and children to increase their social participation and interaction, and to empower them in the exercise of their rights. -

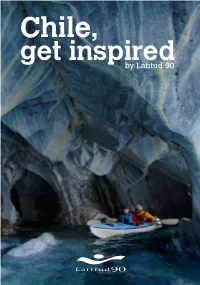

Latitud 90 Get Inspired.Pdf

Dear reader, To Latitud 90, travelling is a learning experience that transforms people; it is because of this that we developed this information guide about inspiring Chile, to give you the chance to encounter the places, people and traditions in most encompassing and comfortable way, while always maintaining care for the environment. Chile offers a lot do and this catalogue serves as a guide to inform you about exciting, adventurous, unique, cultural and entertaining activities to do around this beautiful country, to show the most diverse and unique Chile, its contrasts, the fascinating and it’s remoteness. Due to the fact that Chile is a country known for its long coastline of approximately 4300 km, there are some extremely varying climates, landscapes, cultures and natures to explore in the country and very different geographical parts of the country; North, Center, South, Patagonia and Islands. Furthermore, there is also Wine Routes all around the country, plus a small chapter about Chilean festivities. Moreover, you will find the most important general information about Chile, and tips for travellers to make your visit Please enjoy reading further and get inspired with this beautiful country… The Great North The far north of Chile shares the border with Peru and Bolivia, and it’s known for being the driest desert in the world. Covering an area of 181.300 square kilometers, the Atacama Desert enclose to the East by the main chain of the Andes Mountain, while to the west lies a secondary mountain range called Cordillera de la Costa, this is a natural wall between the central part of the continent and the Pacific Ocean; large Volcanoes dominate the landscape some of them have been inactive since many years while some still present volcanic activity. -

Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty Of

Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brad T. Eidahl December 2017 © 2017 Brad T. Eidahl. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile by BRAD T. EIDAHL has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Patrick M. Barr-Melej Professor of History Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT EIDAHL, BRAD T., Ph.D., December 2017, History Writing the Opposition: Power, Coercion, Legitimacy and the Press in Pinochet's Chile Director of Dissertation: Patrick M. Barr-Melej This dissertation examines the struggle between Chile’s opposition press and the dictatorial regime of Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990). It argues that due to Chile’s tradition of a pluralistic press and other factors, and in bids to strengthen the regime’s legitimacy, Pinochet and his top officials periodically demonstrated considerable flexibility in terms of the opposition media’s ability to publish and distribute its products. However, the regime, when sensing that its grip on power was slipping, reverted to repressive measures in its dealings with opposition-media outlets. Meanwhile, opposition journalists challenged the very legitimacy Pinochet sought and further widened the scope of acceptable opposition under difficult circumstances. Ultimately, such resistance contributed to Pinochet’s defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, initiating the return of democracy. -

Fredrik Reinfeldt

2014 Press release 03 June 2014 Prime Minister's Office REMINDER: German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte to Harpsund On Monday and Tuesday 9-10 June, Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt will host a high-level meeting with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, British Prime Minister David Cameron and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte at Harpsund. The European Union needs to improve job creation and growth now that the EU is gradually recovering from the economic crisis. At the same time, the EU is facing institutional changes with a new European Parliament and a new European Commission taking office in the autumn. Sweden, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands are all reform and growth-oriented countries. As far as Sweden is concerned, it will be important to emphasise structural reforms to boost EU competitiveness, strengthen the Single Market, increase trade relations and promote free movement. These issues will be at the centre of the discussions at Harpsund. Germany, the UK and the Netherlands, like Sweden, are on the World Economic Forum's list of the world's ten most competitive countries. It is natural, therefore, for these countries to come together to compare experiences and discuss EU reform. Programme points: Monday 9 June 18.30 Chancellor Merkel, PM Cameron and PM Rutte arrive at Harpsund; outdoor photo opportunity/door step. Tuesday 10 June 10.30 Joint concluding press conference. Possible further photo opportunities will be announced later. Accreditation is required through the MFA International Press Centre. Applications close on 4 June at 18.00. -

Directing Approaches from Contemporary Chilean Women

EXPANDING THEATRE: DIRECTING APPROACHES FROM CONTEMPORARY CHILEAN WOMEN DIRECTORS A THESIS IN Theatre Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS by MARY ALLISON JOSEPH B.A., University of South Carolina, 2009 Kansas City, Missouri 2020 © 2020 MARY ALLISON JOSEPH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED EXPANDING THEATRE: DIRECTING APPROACHES FROM CONTEMPORARY CHILEAN WOMEN DIRECTORS Mary Allison Joseph, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2020 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the careers, theatrical ideologies, and directing methodologies of three contemporary Chilean women stage directors: Andrea Giadach, Alexandra von Hummel, and Ignacia González. Respective chapters provide an overview of each director’s career that includes mention of formative moments. Each chapter also includes a synthesis of the director’s thinking as distilled from personal interviews and theoretical works, followed by a methodological case study that allows for analysis of specific directing methods, thus illuminating the director’s beliefs in action. In each chapter, the author asserts that the director’s innovative thinking and creative practices constitute expansions of the theatrical artform. Finally, the author traces similarities across the directing approaches of the three directors, which suggest guiding ideas for expanding the theatrical artform. Chapter one explores the directing career of Andrea Giadach, with highlights including her acting experiences in La lluvia de verano (2005) and Mateluna (2012) and her iii directing projects Mi mundo patria (2008) and Penélope ya no espera (2014). Her beliefs about political theatre are illuminated through a directing case study of her 2019 production of El Círculo. -

Permanent War on Peru's Periphery: Frontier Identity

id2653500 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com ’S PERIPHERY: FRONT PERMANENT WAR ON PERU IER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH CENTURY CHILE. By Eugene Clark Berger Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History August, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Date: Jane Landers August, 2006 Marshall Eakin August, 2006 Daniel Usner August, 2006 íos Eddie Wright-R August, 2006 áuregui Carlos J August, 2006 id2725625 pdfMachine by Broadgun Software - a great PDF writer! - a great PDF creator! - http://www.pdfmachine.com http://www.broadgun.com HISTORY ’ PERMANENT WAR ON PERU S PERIPHERY: FRONTIER IDENTITY AND THE POLITICS OF CONFLICT IN 17TH-CENTURY CHILE EUGENE CLARK BERGER Dissertation under the direction of Professor Jane Landers This dissertation argues that rather than making a concerted effort to stabilize the Spanish-indigenous frontier in the south of the colony, colonists and indigenous residents of 17th century Chile purposefully perpetuated the conflict to benefit personally from the spoils of war and use to their advantage the resources sent by viceregal authorities to fight it. Using original documents I gathered in research trips to Chile and Spain, I am able to reconstruct the debates that went on both sides of the Atlantic over funds, protection from ’ th pirates, and indigenous slavery that so defined Chile s formative 17 century. While my conclusions are unique, frontier residents from Paraguay to northern New Spain were also dealing with volatile indigenous alliances, threats from European enemies, and questions about how their tiny settlements could get and keep the attention of the crown. -

This Is Not a Textual Record. This Is Used As an Administrative Marker by the Chnton Presidential Library Staff

Case Number: 2009-1155-F FOIA MARKER This is not a textual record. This is used as an administrative marker by the CHnton Presidential Library Staff. Folder Title: Chile-Summit I, 1998 [Summit of the Americas] [6] Staff Office-Individual: Inter-American Affairs Original OA/ID Number: 1934 Row: Section: Shelf: Position: Stack: 37 6 7 1 V THE WHITE HOUSE WASH INGTON April 10, 1998 MEMORANDUM TO JOHN PODESTA MACK McLARTY JIM STEINBERG GENE SPERLING FROM: THURGOOD MARSHALL, JR. KRIS BALDERSTON ,,yl^ SUBJECT: CABINET PARTICIPATION IN THE CHILE TRIP UPDATE The following attachment is an updated version of the schedule for the Cabinet's participation in the President's trip to Santiago, Chile. Please contact us if you have any questions. Attachment cc: David Beaubaire Nelson Cunningham Nichole Elkon Laura Graham Sara Latham Laura Marcus Elisa Millsap Janet Murguia Ted Piccone Jaycee Pribulsky Steve Ronnel Cabinet Schedules SUMMIT OF THE AMERICAS-SANTIAGO, CHILE ARIL 1998 Time POTUS Schedule Time Cabinet Schedule WEDNESDAY. APRIL 15TH 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route Santiago 8:45 pm Depart AAFB en route [flight time: 10 hours, 15 minutes] Santiago [time change: none] Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey depart RON AIR FORCE ONE RON A IR FORCE ONE THURSDAY APRIL 16TH 7:00 am Arrive Santiago 7:00 Arrive Santiago Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, McCaffrey arrive 7:10 am- Arrival Ceremony 7:10- Arrival Ceremony 7:25 am TARMAC 7:25 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky Santiago Airport McCaffrey attend Open Press 8:00 am Arrive Hyatt Regency Hotel 8:00 am- Down Time 9:30 am Hyatt Regency Hotel 10:25 am- State Arrival Ceremony 10:25- State Arrival Ceremony 10:35 am Courtyard - La Moneda Palace 10:35 Daley, Riley, Barshefsky, Press TBD McCaffrey attend 10:35 am- Restricted Bilateral with President Frei 11:25 am President's Office - La Moneda Palace Official Photo Only Note: Potus plus 5. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

El-Arte-De-Ser-Diaguita.Pdf

MUSEO CHILENO DE ARTE PRECOLOMBINO 35 AÑOS 1 MUSEO CHILENO MINERA ESCONDIDA DE ARTE OPERADA POR PRECOLOMBINO BHP BILLITON 35 AÑOS PRESENTAN Organiza Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino Auspician Ilustre Municipalidad de Santiago Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y de las Artes Proyecto acogido a la Ley de Donaciones Culturales Colaboran Museo Arqueológico de La Serena – DIBAM Museo del Limarí – DIBAM Museo Nacional de Historia Natural – DIBAM Museo Histórico Nacional – DIBAM Museo de Historia Natural de Concepción – DIBAM Museo Andino, Fundación Claro Vial Instituto Arqueológico y Museo Prof. Mariano Gambier, San Juan, Argentina Gonzalo Domínguez y María Angélica de Domínguez Exposición Temporal Noviembre 2016 – Mayo 2017 EL ARTE DE SER DIAGUITA THE ART OF BEING Patrones geométricos representados en la alfarería Diaguita | Geometric patterns depicted in the Diaguita pottery. Gráca de la exposición El arte de ser Diaguita. DIAGUITA INTRODUCTION PRESENTACIÓN We are pleased to present the exhibition, The Art of Being Diaguita, but remains present today in our genetic and cultural heritage, La exhibición El Arte de ser Diaguita, que tenemos el gusto de Esta alianza de más de 15 años, ha dado nacimiento a muchas which seeks to delve into matters related to the identity of one of and most importantly in present-day indigenous peoples. presentar trata de ahondar en los temas de identidad de los pueblos, exhibiciones en Antofagasta, Iquique, Santiago y San Pedro de Chile’s indigenous peoples — the Diaguita, a pre-Columbian culture This partnership of more than 15 years has given rise to many en este caso, de los Diaguitas, una cultura precolombina que existía a Atacama.