Third Eye Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Megalith.Pdf

PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER ETHNOLOGICAL SERIES No. Ill THE MEGALITHIC CULTURE OF INDONESIA Published by the University of Manchester at THE UNIVERSITY PRESS (H. M. MCKECHNIE, Secretary) 12 LIME GROVE, OXFORD ROAD, MANCHESTER LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. LONDON : 39 Paternoster Row : . NEW YORK 443-449 Fourth Avenue and Thirtieth Street CHICAGO : Prairie Avenue and Twenty-fifth Street BOMBAY : Hornby Road CALCUTTA: G Old Court House Street MADRAS: 167 Mount Road THE MEGALITHIC CULTURE OF INDONESIA BY , W. J. PERRY, B.A. MANCHESTEE : AT THE UNIVERSITY PBESS 12 LIME GROVE, OXFOBD ROAD LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. London, New York, Bombay, etc. 1918 PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER No. CXVIII All rights reserved TO W. H. R. RIVERS A TOKEN OF AFFECTION AND REGARD PREFACE. IN 1911 the stream of ethnological research was directed by Dr. Rivers into new channels. In his Presidential Address to the Anthropological Section of the British Association at Portsmouth he expounded some of the effects of the contact of diverse cul- tures in Oceania in producing new, and modifying pre-existent institutions, and thereby opened up novel and hitherto unknown fields of research, and brought into prominence once again those investigations into movements of culture which had so long been neglected. A student who wishes to study problems of culture mixture and transmission is faced with a variety of choice of themes and of regions to investigate. He can set out to examine topics of greater or less scope in circumscribed areas, or he can under- take world-wide investigations which embrace peoples of all ages and civilisations. -

Unit 10:Writing for Children

UNIT 10:WRITING FOR CHILDREN UNIT STRUCTURE 10.1 Learning Objectives 10.2 Introduction 10.3 Children’s Writing 10.4 Some famous children writers of Assam 10.5 How to write 10.6 Changing Trends 10.7 Let Us Sum Up 10.8 Further Readings 10.9 Possible Questions 10.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After going through this unit, you will be able to : describe the various ways of writing for children, discuss some of the famous children writers, write for children get to know about the changing trends in writing for children 10.2 INTRODUCTION Writing for children is essentially an important segment of Creative Writing. Again, Creative Writing is that kind of writing which is done in a free and imaginative way. It can also be called an exercise on free composition on any subject. There are some people who can write anything on any subject very freely. This ability however depends on one’s power of observation, imagination, innovation, presentation and, the last but not least, the power of one’s expression. Again, in order to strengthen the power of expression one must have a good command over language as also a strong vocabulary. Moreover, a person with creativity has that kind of talent which helps him or her discover a new situation and/or new facts in one’s day-to- day life and present them before others in the simplest possible manner. With a keen power of observation, such people can easily create and write a short story, novel, poem or any other writing for children. -

Doctor of Philosophy Riyaz Ahmad Kumar Professor Shugufta Shaheen

Themes and Trends in Contemporary Indian Children’s Literature in English: A Critical Survey Thesis submitted for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English By Riyaz Ahmad Kumar Under the Supervision of Professor Shugufta Shaheen Department of English School of Languages Linguistics and Indology MAULANA AZAD NATIONAL URDU UNIVERSITY Hyderabad-INDIA 2017 D E C L A R A T I O N I do hereby declare that this thesis entitled Themes and Trends in Contemporary Indian Children’s Literature in English: A Critical Survey is original research carried out by me. No part of this thesis was published, or submitted to any other University/Institution for the award of any Degree/Diploma. (Riyaz Ahmad Kumar) Place: Date: C E R T I F I C A T E This is to certify that the thesis entitled Themes and Trends in Contemporary Indian Children’s Literature in English: A Critical Survey, submitted for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, Department of English, School of Languages Linguistics and Indology, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad, is the result of the original research work carried out by Mr. Riyaz Ahmad Kumar under my supervision and to the best of my knowledge and belief, the work embodied in this thesis does not form part of any thesis/dissertation already submitted to any University/Institution for the award of any Degree/Diploma. Signature of Research Supervisor Dr. Shugufta Shaheen Dr. Shugufta Shaheen Head Department of English Prof. Naseemuddin Farees Dean School of Languages Linguistics and -

Assamese Children Literature: an Introductory Study

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(4): 91-97 Article Received: 08th October, 2020; Article Revised: 15th February, 2021; Article Accepted: 20th March, 2021 Assamese Children Literature: An Introductory Study Dalimi Pathak Assistant Professor Sonapur College, Sonapur, Assam, India _________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION : Out of these, she has again shown the children Among the different branches of literature, literature of ancient Assam by dividing it into children literature is a remarkable one. Literature different parts, such as : written in this category for the purpose of the (A) Ancient Assam's Children Literature : children's well being, helps them to raise their (a) Folk literature level children literature mental health, intellectual, emotional, social and (b) Vaishnav Era's children literature moral feelings. Not just only the children's but a real (c) Shankar literature of the later period children's literature touches everyone's heart and (d) Pre-Independence period children literature gives immense happiness. Composing child's Based on the views of both the above literature is a complicated task. This class of mentioned researchers Assamese children literature exist in different languages all over the literature can be broadly divided into three major world. In our Assamese language too multiple levels : numbers of children literature are composed. (A) Assamese Children Literature of the Oral Era. While aiming towards the infant mind and mixing (B) Assamese Children Literature of the Vaishnav the mental intelligence of those kids with their Era. wisdom instinct, imagination and feelings, (C) Assamese Children Literature of the Modern literature in this category will also find a place on Era. the mind of the infants. -

Special Reference to Anubadar Katha by Krishna Kanta Handique)

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Relevance of translation (Special reference to Anubadar Katha by Krishna Kanta Handique) Jyotsna Devi Research scholar Gauhati University Abstract: Krishna Kanta Handique is a helmsman of modern Assamese language who has contributed to the granary of Assamese literature with writings and criticism on Western language and literature. He has also done a great amount of translation from Sanskrit and other European languages. Krishna Kanta Handique analyses various issues and aspects of literature in his original writings. Anubadar Katha by Krishna Kanta Handique is an essay associated to the issues of translation. In this article, he has analysed the role of translation to make a language and literature enrich with certain instances. He also talks about the relevance of translation in Assamese literature too. The objective of the paper is to analyse relevance of translation discussed by Krishna Kanta Handique in his Anubadar Katha Key words: Assamese literature, Krishna Kanta Handique, relevance, translation. Introduction Krishna Kanta Handique was one of the most renowned figures of modern Assamese literature whose contribution to Assamese literature is immense. He is a helmsman of Assamese language and literature with the knowledge of thirteen languages including Sanskrit, Latin, Greek, Russian, Italian, Spanish, Pali etc. Apart from the translation of ancient epical writings such as Yashastilak, Naishadh-Charita, Krishna Kanta Handique has enriched the literary field with his critical writings. Moreover, he has also contributed to the granary of Assamese literature with poems, paintings, philosophy, children literature, biographical writings and criticism on Western language and literature. -

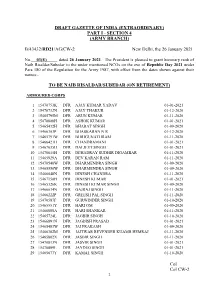

Col Col CW-2 DRAFT GAZETTE of INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I

DRAFT GAZETTE OF INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I - SECTION 4 (ARMY BRANCH) B/43432/RD21/AG/CW-2 New Delhi, the 26 January 2021 No. 03(E) dated 26 January 2021. The President is pleased to grant honorary rank of Naib Risaldar/Subedar to the under mentioned NCOs on the eve of Republic Day 2021 under Para 180 of the Regulation for the Army 1987, with effect from the dates shown against their names:- TO BE NAIB RISALDAR/SUBEDAR (ON RETIREMENT) ARMOURED CORPS 1 15470753K DFR AJAY KUMAR YADAV 01-01-2021 2 15470732N DFR AJAY THAKUR 01-12-2020 3 15465795M DFR ARUN KUMAR 01-11-2020 4 15470808H DFR ASHOK KUMAR 01-01-2021 5 15465432H DFR BHARAT SINGH 01-09-2020 6 15466303P DFR BHASKARAN N R 01-12-2020 7 15465791W DFR BHRIGUNATHRAM 01-11-2020 8 15466421H DFR CHANDRAMANI 01-01-2021 9 15467035H DFR DALJEET SINGH 01-01-2021 10 15470615H DFR DEHADRAY SUDHIR DIGAMBAR 01-11-2020 11 15465929A DFR DEV KARAN RAM 01-11-2020 12 15470540W DFR DHARMENDRA SINGH 01-09-2020 13 15465550W DFR DHARMENDRA SINGH 01-09-2020 14 15466048N DFR DINESH CHANDRA 01-11-2020 15 15467150H DFR DINESH KUMAR 01-01-2021 16 15465326K DFR DINESH KUMAR SINGH 01-09-2020 17 15466034N DFR GAJRAJ SINGH 01-11-2020 18 15466222P DFR GREESH PAL SINGH 01-11-2020 19 15470587F DFR GURWINDER SINGH 01-10-2020 20 15465551Y DFR HARI OM 01-09-2020 21 15466000A DFR HARI SHANKAR 01-11-2020 22 15465724L DFR JAGBIR SINGH 01-10-2020 23 15466891N DFR JAGDISH PRASAD 01-01-2021 24 15465483W DFR JAI PRAKASH 01-09-2020 25 15466302M DFR JAITWAR REVENDER KUAMR HEMRAJ 01-11-2020 26 15465802X DFR JASBIR SINGH 01-11-2020 -

ED240217.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 240 217 UD 023 393 TITLE Selected Multicultural Instructional Materials. INSTITUTION Seattle School District 1, Wash.; Washington Office of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Olympia. PUB DATE Aug 83 NOTE 724p.; Light print. Published by the Office for Multicultural and Equity Education. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRICE MF04/PC29 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Class Activities; *Cultural Activities; Elementary Education; *Ethnic Groups; Foreign Countries; Instructional Materials; *Multicultural Education IDENTIFIERS *Holidays ABSTRACT This is a compilation of ten multicultural instructional booklets that were prepared and published by the Seattle, Washington, School District. The first booklet, entitled "Selected Multi-ethnic/Multicultural Events and Personalities," lists and describes (1) major holidays and events celebrated in the United States, and (2) American ethnic minority and majority individuals and their achievements. Booklet 2, "Chinese New Year," contains background information and classroom activities about that holiday, as well as Korean and Vietnamese New Year's customs. Booklet 3 presents activities and assembly suggestions prepared to assist schools in commemorating January 15, the birthdate of Martin. Luther King, Jr. The information and activities in Booklet 4 focus on the celebration of Afro-American History Month. Booklet 5; "Lei Day," focuses on Hawaiian history, culture, and statehood. Booklet 6 is entitled "Cinco de Mayo," and presents information about the Mexican defeat of French troops in 1862, as well as other Mexican events and cultural activities. Booklet 7 centers around Japan and the Japanese holiday, "Children's Day." The Norwegian celebration "Styyende Mai" (Constitution Day, May 17), is described in Booklet 8, along with other information about and cultural activities from Norway. -

List of Stamps from 1852 Onwards

LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS POSTAGE STAMPS – PRE-INDEPENDENCE Year Denomination Particulars 1 1852 /2a SCINDE DAWK 1 1854 /2a EAST INDIA CO, ISSUES 1a -do- 4a -do- 1854 4a QUEEN VICTORIA 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 1855 4a -do- 8a -do- 1 1856-64 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- UNDER THE CROWN - QUEEN 1860 8p VICTORIA 1 1865 /2a Elephant’s Head Watermark 8p -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- 1866 6a -do- 1866-67 4a Octagonal design 6a8p -do- 1868 8a Die II 1 1873 /2a -do- 1874 9p -do- 1r -do- 1876 6a 12a 1 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 1 1882-88 /2a Empire of India – Queen Victoria 9p -do- 1a -do- 1a6p -do- 2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 4a6p -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1R -do- 1 1891 2 /2a Surcharged 1 1892-97 2 /2a 1r 1895 2r 3r 5r 1 1898 /4a 1899 3p 1900-02 3p 1 /2a 1a 2a 1 2 /2a 1902-11 3p KING EDWARD VII 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 6a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 2 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 3r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1 1905 /4a Surcharged 1 1906 /2a Postage and Revenue 1a -do- 1911 3p KING GEORGE V 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 1 1 /2a -do- 2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 6a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1921 9p Surcharged 1 1922 /4a -do- 1922-26 1a Colours changed 1 1 /2a -do- 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 1926-31 3p Printed at ISP Nasik 1 /2a -do- 1a -do- 1 1 /2a -do- 2a -do- 3 LIST OF STAMPS FROM 1852 ONWARDS 1 2 /2a -do- 3a -do- 4a -do- 8a -do- 12a -do- 1r -do- 2r -do- 5r -do- 10r -do- 15r -do- 25r -do- 1929 2a Air Mail Series 3a -do- 4a -

Eyolf Østrem

thingsTT twice Eyolf Østrem Contents Preface vii IYou’ve Been With the Professors 1 1 Analysing Dylan Songs 3 Methodological Considerations The Object............................ 3 The harmony........................... 7 Analysing an Idea......................... 8 2 ‘Beauty may Only Turn to Rust’ 13 The Beautiful world of Bob Dylan................ 14 Beauty and the Beast....................... 16 Proportion and expression..................... 20 Expression and style........................ 22 3 ‘Going Through All These Things Twice’ 25 The Ritual of a Bob Dylan Concert The External Similarites: Ceremony................ 27 The Rolling Thunder Revue................... 30 The Gospel Years......................... 33 The Voice of a Generation.................... 33 Secular Ritual........................... 37 Functions and means....................... 41 Dylan and ritual revisited..................... 45 Postscript............................. 49 4 The Momentum of Standstill 51 or: Time Out Of Mind and the Blues Dylan and the Blues....................... 53 i ii CONTENTS In the Evening.......................... 53 I Pity The Poor Immigrant.................... 55 Standing (Still) in the Doorway.................. 57 Ring Them Bells......................... 62 Highlands............................ 65 II Harmony and Understanding 67 5 ‘What I learned from Lonnie’ 69 An exploration of some remarks in Chronicles Secrets in the back room..................... 69 Melodies out of triplets – Axioms and numbers.......... 71 Rhythm: The Link Wray ‘Rumble’ -

A Comparative Study of the Shadow Lines and Tamas

Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas A Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab For the Award of Master of Philosophy In Comparative Literature By Pardeep Kaur Supervisor- Dr. Rajinder Kumar Sen Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab, Bathinda July, 2013 CERTIFICATE I declare that the dissertation entitled “Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas” has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. Rajinder Kumar Sen, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Pardeep Kaur) Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: ii CERTIFICATE I certify that Pardeep Kaur has prepared her dissertation entitled “Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas” for the award of M.Phil degree of the Central University of Punjab, under my guidance. She has carried out this work at the Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. Rajinder Kumar Sen) Assistant Professor Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: iii ABSTRACT Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas Name of student : Pardeep Kaur Registration Number : CUP/MPh-PhD/SLLC/CPL/2011-12/07 Degree for which submitted : Master of Philosophy Supervisor : Dr. -

Terroryści (1986) Hou Wyprodukował

5. FESTIWAL FILMOWY PIĘĆ SMAKÓW 5. FIVE FLAVOURS FILM FESTIVAL Spis treści: Hou Hsiao-hsien – biografia............................ 2 Tożsamość wyspy – esej.................................... 3 Focus: Tajwan. Filmy Hou Hsiao-hsiena....... 6 Focus: Tajwan. Nowa Fala................................. 18 Focus: Tajwan. Nowe Kino Tajwanu.............. 24 Taste of Korea. Hong Sang-soo...................... 32 Taste of Korea........................................................ 40 Taste of Korea. Koreańska Noc Grozy........... 48 Nowe Kino Azji..................................................... 52 5. FESTIWAL FILMOWY PIĘĆ SMAKÓW Sushi Typhoon...................................................... 62 Azja w obiektywie............................................... 66 19 – 26 X 2011 – WARSZAWA, KINO MURANÓW i KINO.LAB Wydarzenia towarzyszące................................... 70 26 – 31 X 2011 KRAKÓW, KINO POD BARANAMI / 12 – 15 XI 2011 POZNAŃ, KINO MUZA Indeks...................................................................... 72 Tożsamość wyspy: Hou Hsiao-hsien Niespodziewanej inspiracji dostarczyło tajwańskim filmowcom samo życie: Hou Hsiao-hsien w 1988 roku zmarł prezydent Chang Ching-kuo (syn i następca Chang Kaj-szeka), i kino tajwańskiej Nowej Fali trwający 38 lat stan wyjątkowy został zniesiony, zliberalizowano cenzurę i dotychczasowe tabu mogły stać się tematem filmów. Najważniejszym z nich był Incydent 28 lutego, kiedy w czasie trwającej miesiąc pacyfikacji wyspy Na Tajwanie historia kina splata się z burzliwymi losami kraju, który