Territorial Management in Indigenous Matrifocal Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

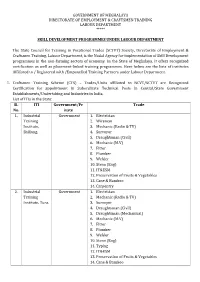

Skill Development Programmes Under Labour Department

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA DIRECTORATE OF EMPLOYMENT & CRAFTSMEN TRAINING LABOUR DEPARTMENT ***** SKILL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES UNDER LABOUR DEPARTMENT The State Council for Training in Vocational Trades (SCTVT) Society, Directorate of Employment & Craftsmen Training, Labour Department, is the Nodal Agency for implementation of Skill Development programmes in the non-farming sectors of economy in the State of Meghalaya. It offers recognized certification as well as placement-linked training programmes. Here below are the lists of institutes Affiliated to / Registered with /Empanelled Training Partners under Labour Department. 1. Craftsmen Training Scheme (CTS) – Trades/Units affiliated to NCVT/SCTVT are Recognized Certification for appointment in Subordinate Technical Posts in Central/State Government Establishments/Undertaking and Industries in India. List of ITIs in the State: Sl. ITI Government/Pr Trade No. ivate 1. Industrial Government 1. Electrician Training 2. Wireman Institute, 3. Mechanic (Radio & TV) Shillong. 4. Surveyor 5. Draughtsman (Civil) 6. Mechanic (M.V) 7. Fitter 8. Plumber 9. Welder 10. Steno (Eng) 11. IT&ESM 12. Preservation of Fruits & Vegetables 13. Cane & Bamboo 14. Carpentry 2. Industrial Government 1. Electrician Training 2. Mechanic (Radio & TV) Institute, Tura. 3. Surveyor 4. Draughtsman (Civil) 5. Draughtsman (Mechanical) 6. Mechanic (M.V) 7. Fitter 8. Plumber 9. Welder 10. Steno (Eng) 11. Typing 12. IT&ESM 13. Preservation of Fruits & Vegetables 14. Cane & Bamboo 15. Carpentry 3. Industrial Government 1. Dress Making Training 2. Hair & Skin Institute 3. Dress Making (Advanced) (Women), Shillong 4. Govt. Government 1. Wireman Industrial 2. Plumber Training 3. Mason (Building Constructor) Institute, Sohra 4. Painter General 5. Office Assistant cum Computer Operator 5. -

The Origins and Consequences of Kin Networks and Marriage Practices

The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices by Duman Bahramirad M.Sc., University of Tehran, 2007 B.Sc., University of Tehran, 2005 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences c Duman Bahramirad 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Duman Bahramirad Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Economics) Title: The origins and consequences of kin networks and marriage practices Examining Committee: Chair: Nicolas Schmitt Professor Gregory K. Dow Senior Supervisor Professor Alexander K. Karaivanov Supervisor Professor Erik O. Kimbrough Supervisor Associate Professor Argyros School of Business and Economics Chapman University Simon D. Woodcock Supervisor Associate Professor Chris Bidner Internal Examiner Associate Professor Siwan Anderson External Examiner Professor Vancouver School of Economics University of British Columbia Date Defended: July 31, 2018 ii Ethics Statement iii iii Abstract In the first chapter, I investigate a potential channel to explain the heterogeneity of kin networks across societies. I argue and test the hypothesis that female inheritance has historically had a posi- tive effect on in-marriage and a negative effect on female premarital relations and economic partic- ipation. In the second chapter, my co-authors and I provide evidence on the positive association of in-marriage and corruption. We also test the effect of family ties on nepotism in a bribery experi- ment. The third chapter presents my second joint paper on the consequences of kin networks. -

Mon-Khmer Studies Volume 41

Mon-Khmer Studies VOLUME 42 The journal of Austroasiatic languages and cultures Established 1964 Copyright for these papers vested in the authors Released under Creative Commons Attribution License Volume 42 Editors: Paul Sidwell Brian Migliazza ISSN: 0147-5207 Website: http://mksjournal.org Published in 2013 by: Mahidol University (Thailand) SIL International (USA) Contents Papers (Peer reviewed) K. S. NAGARAJA, Paul SIDWELL, Simon GREENHILL A Lexicostatistical Study of the Khasian Languages: Khasi, Pnar, Lyngngam, and War 1-11 Michelle MILLER A Description of Kmhmu’ Lao Script-Based Orthography 12-25 Elizabeth HALL A phonological description of Muak Sa-aak 26-39 YANIN Sawanakunanon Segment timing in certain Austroasiatic languages: implications for typological classification 40-53 Narinthorn Sombatnan BEHR A comparison between the vowel systems and the acoustic characteristics of vowels in Thai Mon and BurmeseMon: a tendency towards different language types 54-80 P. K. CHOUDHARY Tense, Aspect and Modals in Ho 81-88 NGUYỄN Anh-Thư T. and John C. L. INGRAM Perception of prominence patterns in Vietnamese disyllabic words 89-101 Peter NORQUEST A revised inventory of Proto Austronesian consonants: Kra-Dai and Austroasiatic Evidence 102-126 Charles Thomas TEBOW II and Sigrid LEW A phonological description of Western Bru, Sakon Nakhorn variety, Thailand 127-139 Notes, Reviews, Data-Papers Jonathan SCHMUTZ The Ta’oi Language and People i-xiii Darren C. GORDON A selective Palaungic linguistic bibliography xiv-xxxiii Nathaniel CHEESEMAN, Jennifer -

Megalith.Pdf

PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER ETHNOLOGICAL SERIES No. Ill THE MEGALITHIC CULTURE OF INDONESIA Published by the University of Manchester at THE UNIVERSITY PRESS (H. M. MCKECHNIE, Secretary) 12 LIME GROVE, OXFORD ROAD, MANCHESTER LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. LONDON : 39 Paternoster Row : . NEW YORK 443-449 Fourth Avenue and Thirtieth Street CHICAGO : Prairie Avenue and Twenty-fifth Street BOMBAY : Hornby Road CALCUTTA: G Old Court House Street MADRAS: 167 Mount Road THE MEGALITHIC CULTURE OF INDONESIA BY , W. J. PERRY, B.A. MANCHESTEE : AT THE UNIVERSITY PBESS 12 LIME GROVE, OXFOBD ROAD LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. London, New York, Bombay, etc. 1918 PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER No. CXVIII All rights reserved TO W. H. R. RIVERS A TOKEN OF AFFECTION AND REGARD PREFACE. IN 1911 the stream of ethnological research was directed by Dr. Rivers into new channels. In his Presidential Address to the Anthropological Section of the British Association at Portsmouth he expounded some of the effects of the contact of diverse cul- tures in Oceania in producing new, and modifying pre-existent institutions, and thereby opened up novel and hitherto unknown fields of research, and brought into prominence once again those investigations into movements of culture which had so long been neglected. A student who wishes to study problems of culture mixture and transmission is faced with a variety of choice of themes and of regions to investigate. He can set out to examine topics of greater or less scope in circumscribed areas, or he can under- take world-wide investigations which embrace peoples of all ages and civilisations. -

What I Wish My College Students Already Knew About PRC History

Social Education 74(1), pp 12–16 ©2010 National Council for the Social Studies What I Wish My College Students Already Knew about PRC History Kristin Stapleton ifferent generations of Americans understand China quite differently. This, Communist Party before 1949 because of course, is true of many topics. However, the turbulence of Chinese they believed its message of discipline Dhistory and U.S.-China relations in the 60 years since the founding of the and “power to the people” could unify People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949 has deepened the gaps in generational the country, defeat the Japanese invad- thinking about China.1 If you came of age in the America of the 1950s and 1960s, ers, and sweep out the weak, corrupt you remember when China seemed like North Korea does today—isolated, aggres- Nationalist government. sive, the land of “brain washing.” If you first learned about China in the 1970s, Like Wild Swans, other memoirs then perhaps, like me, you had teachers who were inspired by Maoist rhetoric and of the Red Guard generation explore believed young people could break out of the old culture of self-interest and lead why children born after the Communist the world to a more compassionate future. The disillusion that came with more “Liberation” of China in 1949 put such accurate understanding of the tragedies of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural faith in Mao and his ideas.2 Certainly Revolution led some of us to try to understand China more fully. Many of my the cult of personality played a major college-age students, though, seem to have dismissed most PRC history as just role. -

Govt. of Meghalaya Constitute the District Legal Services Authority In

NOTIFICATION Dated Shillong, the 24th February,2015. No. LA (B) 7/99/304- In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of Section 9 of the Legal Services Authority Act, 1987 read with Rule 10 of the Meghalaya_State · Legal Services Authority Rules, 1998,and in consultation with the· Hig-h Court of ~leghalaya, the Government of Meghalaya, hereby constitute the District Legal Servi - ·. Authority in West· -..; Khasi Hills District of the State- with the following members. ~ ~ 0·~~- ...,, 1"'-7 "Zc~ 1. The District & Sessions Judge, .. Chairman /jO'/ . /f1!.: I \'~~ West Khasi Hills District, Nongstoin l!f..J ; B L015 \ C 2. The Chief Judicial Magistrate, Secretary· ~~ i 26r E I (' '5 ' r r. West Khasi Hills District, Nongstoin ..·· . "· / .... .'\ ., ,. ~ q 1..-t 'YI(;;; 3. Add!. Deputy Commissioner (Judicial) , Member _ "\,,,.,...-....... .? ) /" r-, \, vch··,, -........! .... West Khasi Hills District, Nongstoin ~. (., ., -·.- 4. j The Superintendent of Police, Member - ..... West Khasi Hills District, Nongstoin 5. The Govt. Pleader/Public Prosecutor, Member West Kh.asi Hills District, Nongstoin 6. Smti F Marcelline Rymbai, Mawkhlam- Non-Official Member Nongpyndeng, B.P.O.- Nongpyndeng, West Khasi (Lady) , Hills District,Nongstoin-793119. The Notification No. LA.7/99/41, dated 3/12/2001, relatmg to constltuuon of District Legal Services Authority of West Khasi Hills District stands superseded. \:'~ ( L.M Sangma ) Secretary to the Govt. of Meghalaya, Law Department. Memo. No.LA (B) 7/99/304 -A, Dated Shillong, the 24th February, 2015. Copy forwarded to : J.. The Dit·ector of Printing & Station~.n', iviegha!Jya, ~~hillong for publishing the Notification in the next issue of the Gazette of Meghalaya. -

Volume 4-2:2011

JSEALS Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Managing Editor: Paul Sidwell (Pacific Linguistics, Canberra) Editorial Advisory Board: Mark Alves (USA) George Bedell (Thailand) Marc Brunelle (Canada) Gerard Diffloth (Cambodia) Marlys Macken (USA) Brian Migliazza (USA) Keralapura Nagaraja (India) Peter Norquest (USA) Amara Prasithrathsint (Thailand) Martha Ratliff (USA) Sophana Srichampa (Thailand) Justin Watkins (UK) JSEALS is the peer-reviewed journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, and is devoted to publishing research on the languages of mainland and insular Southeast Asia. It is an electronic journal, distributed freely by Pacific Linguistics (www.pacling.com) and the JSEALS website (jseals.org). JSEALS was formally established by decision of the SEALS 17 meeting, held at the University of Maryland in September 2007. It supersedes the Conference Proceedings, previously published by Arizona State University and later by Pacific Linguistics. JSEALS welcomes articles that are topical, focused on linguistic (as opposed to cultural or anthropological) issues, and which further the lively debate that characterizes the annual SEALS conferences. Although we expect in practice that most JSEALS articles will have been presented and discussed at the SEALS conference, submission is open to all regardless of their participation in SEALS meetings. Papers are expected to be written in English. Each paper is reviewed by at least two scholars, usually a member of the Advisory Board and one or more independent readers. Reviewers are volunteers, and we are grateful for their assistance in ensuring the quality of this publication. As an additional service we also admit data papers, reports and notes, subject to an internal review process. -

David Scott in North-East India 1802-1831

'Its interesting situation between Hindoostan and China, two names with which the civilized world has been long familiar, whilst itself remains nearly unknown, is a striking fact and leaves nothing to be wished, but the means and opportunity for exploring it.' Surveyor-General Blacker to Lord Amherst about Assam, 22 April, 1824. DAVID SCOTT IN NORTH-EAST INDIA 1802-1831 A STUDY IN BRITISH PATERNALISM br NIRODE K. BAROOAH MUNSHIRAM MANOHARLAL, NEW DELHI TO THE MEMORY OF DR. LALIT KUMAR BAROOAH PREFACE IN THE long roll of the East India Company's Bengal civil servants, placed in the North-East Frontier region. the name of David Scott stands out, undoubtably,. - as one of the most fasci- nating. He served the Company in the various capacities on the northern and eastern frontiers of the Bengal Presidency from 1804 to 1831. First coming into prominrnce by his handling of relations with Bhutan, Sikkim, and Tibet during the Nepal war of 1814, Scott was successively concerned with the Garo hills, the Khasi and Jaintia hills and the Brahma- putra valley (along with its eastern frontier) as gent to the Governor-General on the North-East Frontier of Bengal and as Commissioner of Assam. His career in India, where he also died in harness in 1831, at the early age of forty-five, is the subject of this study. The dominant feature in his ideas of administration was Paternalism and hence the sub-title-the justification of which is fully given in the first chapter of the book (along with the importance and need of such a study). -

Acquisition of Land for Up-Gradation to 2-Lane of NH44E-Shillong-Nongstoin-Tura Road From

GOVERNMENT OF MEGHALAYA REVENUE & DISASTER MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT SHILLONG. FORM VIII (See rule (1) of rule 13) Declaration No: ____________ Date: __________________ Whereas it appears to the Government that a total of 13203.50 Sq.meters land is required from Mawpun-H up-to Shahlang villages District West Khasi Hills for public purpose, namely, for up-gradation to 2-Lane of NH44E-Shillong-Nongstoin-Tura Road- 41.600Kms-93.800Kms) (renamed as NH127B) Therefore declaration is made that the plot of land measuring more or less 13203.50 Sq.meters of standard measurement in the Villages from from Mawpun-H up-to Shahlang villages District West Khasi Hills as per detail scheduled description enclosed is under acquisition for the above said project and is required to be taken by the Government for public purposes :- This declaration is made under section 19 (1) of Act No. 30/2013 after hearing of objections of persons interested and due enquiry as provided u/s 15 of the Act No-30/2013. The number of families likely to be resettled due to Land Acquisition is NIL for whom Resettlement area has been identified, whose brief description is as followings:- Village NIL District______NIL_____Area___NIL___ The Map/plan of the above land may be inspected in the office of the District Collector West Khasi Hills District Nongstoin on any working day. A summary of the Rehabilitation and Resettlement Scheme is appended. Approved Jt. Secretary to the Govt.of Meghalaya Revenue & Disaster Management Department, Shillong. SCHEDULE OF BOUNDARIES IN RESPECT OF LAND FOR UP-GRADATION TO TWO LANE OF NH44E- SHILLONG-NONGSTOIN-TURA ROAD PORTION NH127B- SUNAPAHAR-NONGSHRAM(41.600Kms- 93.8Kms) Sl.No. -

Languages of the World--Indo-Pacific Fascicle Eight

REPORT RESUMES ED 010 367 48 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD--INDO-PACIFIC FASCICLE EIGHT. ST- VOEGELI1, C.F. VOEGELIN, FLORENCE M. INDIANA UNIV., BLOOMINGTON REPORT NUMBER NDEA- VI -63 -20 PUB DATE. APR 66 CONTRACT OEC-SAE-9480 FURS PRICE MF-$Q.18HC-52.80 70P. ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS, 8(4)/1-64, APRIL 1966 DESCRIPTORS- *LANGUAGES, *INDO PACIFIC LANGUAGES, ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA THIS REPORT DESCRIBES SOME OF THE LANGUAGES AND LANGUAGE FAMILIES OF THE SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA REGIONS OF THE INDO-PACIFIC AREA. THE LANGUAGE FAMILIES DISCUSSED WERE JAKUM, SAKAI, SEMANG, PALAUNG-WA (SALWEEN), MUNDA, AND DRAVIDIAN. OTHER LANGUAGES DISCUSSED WERE ANDAMANESE, N/COBAnESE, KHASI, NAHALI, AND BCRUSHASKI. (THE REPORT IS PART OF A SERIES, ED 010 350 TO ED 010 367.) (JK) +.0 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION AND WELFARE b D Office of Education tr's This document has been reproduced exactlyas received from the S.,4E" L es, C=4.) person or organiz3t1on originating It. Points of view or opinions T--I stated do not nocessart- represent official °dice of Edumdion poeWon or policy. AnthropologicalLinguistics Volume 8 Number 4 April 116 6 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD: INDO- PACIFIC FASCICLE EIGHT A Publication of the ARCHIVES OFLANGUAGES OF THEWORLD Anthropology Department Indiana University ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS is designed primarily, but not exclusively, for the immediate publication of data-oriented papers for which attestation is available in the form oftape recordings on deposit in the Archives of Languages of the World. -

A Comparative Study of the Shadow Lines and Tamas

Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas A Dissertation submitted to the Central University of Punjab For the Award of Master of Philosophy In Comparative Literature By Pardeep Kaur Supervisor- Dr. Rajinder Kumar Sen Centre for Comparative Literature School of Languages, Literature and Culture Central University of Punjab, Bathinda July, 2013 CERTIFICATE I declare that the dissertation entitled “Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas” has been prepared by me under the guidance of Dr. Rajinder Kumar Sen, Assistant Professor, Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. No part of this dissertation has formed the basis for the award of any degree or fellowship previously. (Pardeep Kaur) Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: ii CERTIFICATE I certify that Pardeep Kaur has prepared her dissertation entitled “Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas” for the award of M.Phil degree of the Central University of Punjab, under my guidance. She has carried out this work at the Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab. (Dr. Rajinder Kumar Sen) Assistant Professor Centre for Comparative Literature, School of Languages, Literature and Culture, Central University of Punjab, Bathinda-151001. Date: iii ABSTRACT Revisiting History and the Question of Identity: A Comparative Study of The Shadow Lines and Tamas Name of student : Pardeep Kaur Registration Number : CUP/MPh-PhD/SLLC/CPL/2011-12/07 Degree for which submitted : Master of Philosophy Supervisor : Dr. -

Female Inheritance, Inmarriage, and the Status of Women

Keeping It in the Family: Female Inheritance, Inmarriage, and the Status of Women Duman Bahrami-Rad∗ October 15, 2019 Abstract While female property ownership is associated with positive outcomes for women, their right to inherit property in male-dominated societies may also result in more constraining marriage and gen- der norms. I develop and test the following hypothesis: Where a woman inherits property, her male relatives are more likely to arrange her marriage within the same community in order to avoid frag- mentation of the land. Arranging the marriage also requires controlling the woman’s relations and mobility, which negatively impacts her economic participation. By analyzing datasets on pre-industrial societies and Indonesian individuals, I find that female inheritance is associated with a higher preva- lence of cousin and arranged marriages as well as lower female economic participation and premarital sexual freedom. Using a difference-in-differences design that exploits exogenous variation induced by a reform of inheritance laws in India, I also provide evidence for a causal effect of female inheritance on cousin marriage and female economic participation rates. These findings have implications for the evolution of marriage and gender norms in Islamic societies, where female inheritance is mandated by Islamic law. JEL classifications: D01, J12, J16, N30, Z12, Z13 Keywords: female inheritance, culture, gender inequality, marriage, female economic participation ∗Harvard University, Department of Human Evolutionary Biology. Email: