Guide to the Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

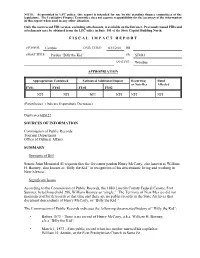

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 82 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2007 Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial Jennifer Nez Denetdale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. "Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial." New Mexico Historical Review 82, 3 (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol82/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival HISTORY, DINE/NAVAJO MEMORY, AND THE BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL Jennifer Nez Denetdale n 4 June 2005, hundreds ofDine and their allies gathered at Fort Sumner, ONew Mexico, to officially open the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Sitting under an arbor, visitors listened to dignitaries interpret the meaning of the Long Walk, explain the four years ofimprisonment at the Bosque Redondo, and discuss the Navajos' return to their homeland in1868. Earlier that morn ing, a small gathering ofDine offered their prayers to the Holy People. l In the past twenty years, historic sites have become popular tourist attrac tions, partially as a result ofpartnerships between state historic preservation departments and the National Park Service. With the twin goals ofeducat ing the public about the American past and promoting their respective states as attractive travel destinations, park officials and public historians have also included Native American sites. -

Navajo Nation to Obtain an Original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 Document

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2019 Navajo Nation to obtain an original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 document WINDOW ROCK – Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer are pleased to announce the generous donation of one of three original Navajo Treaty of 1868, also known as Naaltsoos Sání, documents to the Navajo Nation. On June 1, 1868, three copies of the Treaty of 1868 were issued at Fort Sumner, N.M. One copy was presented to the U.S. Government, which is housed in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington D.C. The second copy was given to Navajo leader Barboncito – its current whereabouts are unknown. The third unsigned copy was presented to the Indian Peace Commissioner, Samuel F. Tappan. The original document is also known as the “Tappan Copy” is being donated to the Navajo Nation by Clare “Kitty” P. Weaver, the niece of Samuel F. Tappan, who was the Indian Peace Commissioner at the time of the signing of the treaty in 1868. “On behalf of the Navajo Nation, it is an honor to accept the donation from Mrs. Weaver and her family. The Naaltsoos Sání holds significant cultural and symbolic value to the Navajo people. It marks the return of our people from Bosque Redondo to our sacred homelands and the beginning of a prosperous future built on the strength and resilience of our people,” said President Nez. Following the signing of the Treaty of 1868, our Diné people rebuilt their homes, revitalized their livestock and crops that were destroyed at the hands of the federal government, he added. -

Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Thanks to the New Mexico Humanities Council and the Western National Parks and Monuments Association for their important contributions to this study. DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Apache, Coconino, Navajo Counties, Arizona; Bernalillo, Cibola, De Baca, Guadalupe, Lincoln, McKinley, Mora, Otero, Santa Fe, Sandoval, Torrance, Valencia Counties, New Mexico The purpose of this study is to evaluate the suitability and feasibility of designating the routes known as the “Long Walk” of the Mescalero Apache and the Navajo people (1862-1868) as a national historic trail under the study provisions of the National Trails System Act (Public Law 90-543). This study provides necessary information for evaluating the national significance of the Long Walk, which refers to the U.S. Army’s removal of the Mescalero Apache and Navajo people from their homelands to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in eastern New Mexico, and for potential designation of a national historic trail. Detailed administrative recommendations would be developed through the subsequent preparation of a comprehensive management plan if a national historic trail is designated. The three criteria for national historic trails, as defined in the National Trails System Act, have been applied and have been met for the proposed Long Walk National Historic Trail. The trail routes possess a high degree of integrity and significant potential for historical interest based on historic interpretation and appreciation. -

Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 10-2-1909 Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub. Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news Recommended Citation Review Pub. Co.. "Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news/9 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lie rort Sumner Review VOL 2--- 12. FORT SUMNER, (Sunnyside Post office), GUADALUPE COUNTY, N. M., OCTOBER 2, 1909. $1 A YEAR, CASH. JL Murder of Miss Hattonl. Thc !oenf of the ,imeis with-- ! The Small Holding . in a mue or aanta Kosa, among ; LOCALETTES i I at Santa Rosa. ' the hilla overlooking the city, Claims. and while wild, yet the roitd (Special Correspondence. ) within a short distance is much AU persons who are .claiming Rosa, N M, Sept. 27- .- land because they have lived on Our Invitation George B. Deen, wife, and Santa traveled. Miss 18, the same for years little son, were called to Portales Sarah Hatton, daughter Miss Hatton was a beautiful twent' or Mrs. R. I. young i more, these claims 'being com- - Tuesday to attend the funeral of Mr. and Hatton of lady, a leader among the of a little nephew. Los Tanos, a small station on the young folks of her town and had monly kno.wn as "small holding Rack Island, nine miles east of many friends here. -

Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson Was Born in Madison County, Kentucky on December 24, 18092, Christmas Eve, to Lindsey and Rebecca Carson

Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson1 Christopher Houston “Kit” Carson was born in Madison County, Kentucky on December 24, 18092, Christmas Eve, to Lindsey and Rebecca Carson. There were already ten other children in the family by the time Christopher was born: five from Lindsey’s first wife, Lucy Bradley, and five from his second, Rebecca Robertson; they went on to have four more children. Lindsey Carson was originally from Iredell County, North Carolina and Rebecca Robertson was from Greenbrier County, Virginia.3 Lindsey and Lucy lived in Iredell County until the urge to follow Daniel Boone drew them Westward (probably between 1773 and 1782). In 1773 Lindsey loaded his wagon with his wife Lucy and their four children: William, Sarah, Andrew, and Moses, and followed where Boone had led over the uneven, rutted Wilderness Road. Soon after their arrival in Kentucky, a second daughter, Sophie, was born. Not long afterward Lucy died. Two years later, Lindsey married Rebecca Robertson. Six of their children were born in Kentucky: Elizabeth, Nancy, Robert, Matilda, Hamilton, and Christopher Houston. He came into the world the day before Christmas in 1809, making thirteen persons to share the log cabin Lindsey had built on Tate’s Creek in Madison, County, Kentucky. When Christopher was about two years old, Lindsey moved the family to Howard County, Missouri where Christopher grew up.4 Lindsey lost his life working at his endless project of clearing the land. One day in early September 1818, while he was working near a burning tree, a flaming limb broke away and fell on him, killing him instantly. -

The Navajo: a Brief History

TheThe NavajoNavajo: A Brief HistorHistory:y According to scientists who study different cultures, the first Navajo lived in western Canada some one thousand years ago. They belonged to an American Indian group called the Athapaskans and they called themselves "Dine" or "The People". As time passed, many of the Athapaskans migrated southward and some settled along the Pacific Ocean. They still live there today and belong to the Northwest Coast Indian tribes. A number of Athapaskan bands, including the first Navajos, migrated southwards across the plains and through the mountains. It was a long, slow trip, but the bands weren't in a hurry. When they found a good place to stay, they would often live there for a long period of time and then move on. For hundreds of years, the early Athapaskan bands followed the herds of wandering animals and searched for good gathering grounds. Scientists, believe that some Athapaskan bands first came to the American Southwest around the year 1300. Some settled in southern Arizona and New Mexico and became the different Apache tribes. Apache languages sound very much like Navajo. The Navajo Athapaskans settled among the mesas, canyons, and rivers of northern New Mexico. The first Navajo land was called Dine’tah. Three rivers - the San Juan, the Gobernador, and the Largo ran through Dine’tah, which was situated just east of Farmington, New Mexico. By the year 1400, the Navajos came in touch with Pueblo Indians. The Navajos learned farming from the Pueblo Indians and by the 1600s, they had become fully capable of raising their own food. -

Museum of New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES FORT SUMNER BRIDGE: THE TESTING OF TWO SITES AND A DATA RECOVER PLAN FOR LA 111917, DE BACA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO Peter Y. Bullock Submitted by Yvonne R. Oakes Principal Investigator ARCHAEOLOGY NOTES 212 SANTA FE 1997 NEW rnXIC0 ADMINISTRATIVE SUMMARY Between September 30, 1996, and January 28, 1997, the Office of Archaeological Studies, Museum of NewMexico, conducted limited testingat two sites in Fort Sumner, De Baca County, New Mexico. Limited testing was conductedat LA 111917 andLA 11 1918 at the request of the New Mexico State Highway andTransportation Department (NMSHTD) to determine the extent and importanceof cultural resources within the proposedproject area of planned improvements to U.S. 60 in Fort Sumner. The two sites are surface ceramic and lithic artifact scatters: peripheral portions of larger habitation sites. No intact cultural features or deposits were found at LA 11 1918. The resources have been adequately documented, and no additional investigations are recommended. Two intact stratified midden deposits were found within the proposedproject limits at LA 111917. We recommend that data recovery investigations be conducted at LA 111917. A third site, LA 111919, was originally within the proposed project area. After changes in project limits, resurvey of this site during testing showed that it is completely outside of the project area. Submitted in fulfillment of Joint Powers Agreement 500122 between the New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department and the Officeof Archaeological Studies, Museum of New Mexico. CPRC Archaeological Survey Permit No. SP-96-027 NMSHTD Project BR-(US)-060-5(31)327, CN 1683 MNM Project 41.623 (Fort Sumner Bridge) iii CONTENTS Administrative Summary ........................................ -

HISTORIC HOMESTEADS and RANCHES in NEW MEXICO: a HISTORIC CONTEXT R

HISTORIC HOMESTEADS AND RANCHES IN NEW MEXICO: A HISTORIC CONTEXT r Thomas Merlan Historic Preservation Division, Office of Cultural Affairs, State ofNew Mexico, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 87501. Professional Services Contract No. 08505 70000021, Department of Cultural Affairs, March, 2008 Prepared for: Historic Homestead Workshop, September 25-26,2010 HISTORIC HOMESTEADS AND RANCHES IN NEW MEXICO: A HISTORIC CONTEXT Thomas Merlan Historic Preservation Division, Office ofCultural Affairs, State ofNew Mexico, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 87501. Professional Services Contract No. 08505 70000021, Department of Cultural Affairs, March, 2008 Prepared for: Historic Homestead Workshop, September 25 -26, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... i HOMESTEAD AND RANCH CHRONOLOGY ... .. ...................................................... ...................... iii 1 GENERAL HISTORY OF RANCHES AND HOMESTEADS IN NEW MEXICO ......................... 1 Sheep Ranching and Trade ..................................................................... ................... ... ... ......................... 1 Human Behavior-Sheep Ranching ........................................................................................................ 6 Clemente Gutierrez ....................................... ........................................................................................ 6 Mariano Chaves y Castillo .............. -

The Bosque Redondo Memorial Long Deserved, Long Overdue

BOSQUE REDONDO The Bosque Redondo Memorial Long Deserved, Long Overdue BY JOSE CISNEROS Director, Museum of New Mexico State Monuments and GREGORY SCOTT SMITH Manager, Fort Sumner State Monument eginning in 1863, the U.S. Army forcibly relocated thou- like cattle by Carleton’s field commander, Colonel sands of Navajo men, women and children from their Christopher “Kit” Carson. Bhomeland in present-day northeastern Arizona and In his latest history of the Navajos, entitled DINE, author northwestern New Mexico to the Bosque Redondo Indian Paul Iverson calls the Long Walk what it really was: a forced Reservation at Fort Sumner, a distance of about 450 miles. march driven by harshness and cruelty. And it was not one Hundreds died en route, in particular the very old and the forced march but several, with at least a dozen different very young. Hundreds more died on the reservation. groups traveling four different routes between Fort Defiance Those who survived what came to be known as the Long and Fort Sumner. Regardless of the heat of the summer or Walk faced a harsh struggle for survival on the desolate plains the cold of the winter, the soldiers escorting them pushed of eastern New Mexico. Some succumbed to pneumonia or the people as fast as they could go. According to stories of dysentery, a few died in fights with the soldiers, others sim- survivors, stragglers, no matter their age or their health, ply starved to death. The conditions at Fort Sumner spared including women who were in the throes of childbirth, no one, and many Navajos buried both their parents and might be shot for falling out of line. -

Kit Carson: Pathbreaker, Patriot and Humanitarian

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 1 Number 4 Article 2 10-1-1926 Kit Carson: Pathbreaker, Patriot and Humanitarian Francis T. Cheetham Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Cheetham, Francis T.. "Kit Carson: Pathbreaker, Patriot and Humanitarian." New Mexico Historical Review 1, 4 (1926). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol1/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. ADVERTISEMENT FOR THE RUNAWAY BOY, C. CARSON NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW Vol. I. October, 1926. No.4. KIT CARSON Pathbreaker, Patriot and Humanitarian By F. T. CHEETHAM Just one hundred years ago, next month, there arrived in Santa Fe, with a belated caravan from the Missouri River, a run-away boy of sixteen years, who was destined to win the spurs of fame on the American frontier. Though of such tender years, he possessed a modesty of demeanor coupled with a firm self-reliance that became outstanding characteristics of his career. His name was Christopher Carson, but he soon became affectionately know by all who knew and loved him as "Kit" Carson. During the two years next preceding he had .b.een ap prenticed to David Workman in a saddlery. He loved the great out-of-doors and the work at a bench became irk some to him. He therefore ran away. -

Jesus Arviso Biography (Ca

Jesus Arviso Biography (ca. 1847 - 1932) Mexican captive and Navajo interpreter, he was born in the state of Sonora, Mexico. About 1850, while yet a child, he was stolen by Apaches from Arizona and held captive for about 5 months. He was treated badly by them, but finally was exchanged for a black pony to a Navajo named B’ee Lizhini “Black Shirt”, at Dusty, New Mexico. Jesus was raised by the Navajo and lived with the band of the headman Tl’aii, “Lefty”. During the Canby Campaign of 1860–1861, Arviso was sent by his Navajo masters on No- vember 19, 1860, to ask for peace of troops operating near Oak Springs south of Fort Defiance. Approaching the troops on horseback he waved a piece of white sheepskin as a flag of truce, shout- ing in Spanish to the troops. Captain Lafayette McLaws, commanding, ordered the troops to hold their fire. Arviso approached and stated his message, but Captain McLaws, not being authorized to grant peace, offered him the choice of either returning to the Navaos or remaining with the troops to serve as guide. Jesus accepted the offer as guide and though yet quite youthful he proved very knowledgable with the country. McLaws later proposed paying him as the principal guide stating that he was the best to be had. In 1863 Arviso served as Navajo interpreter at Fort Wingate. At this time he accompanied three Navajo headmen – Barboncito, Delgadito and Sarracino to that post from the area beyond Zuni to discuss Carleton’s surrender with colonel Chavez, Commander at Ft.