HISTORIC HOMESTEADS and RANCHES in NEW MEXICO: a HISTORIC CONTEXT R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College Disability Offices New Mexico

College Disability Offices New Mexico Four-year Colleges and Universities Diné College Eastern New Mexico University (ENMU) Student Success Center, Disability Support Services Disability Services and Testing, Portales, NM Shiprock, NM 575-562-2280 928-724-6855 (main campus number in Tsaile, AZ) www.sfcc.edu/disability_services www.dinecollege.edu/services/student-services.php Navajo Technical University Institute of American Indian Arts Student Support Services, Crownpoint, NM Disability Support Services, Santa Fe, NM 505-786-4138 505-424-5707 www.navajotech.edu/campus-life/student-support- iaia.edu/student-success-center/disability-support- services services/ New Mexico Institute for Technology (NM Tech) New Mexico Highlands University (NMHU) Counseling and Disability Services, Socorro, NM Office of Accessibility Services, Las Vegas, NM 575-835-6619 505-454-3252 www.nmt.edu/disability-services www.nmhu.edu/campus-services/accessibility-services/ Northern New Mexico College New Mexico State University (NMSU) Accessibility Resource Center, Espanola, NM Student Accessibility Services, Las Cruces, NM 505-747-2152 575-646-6840 nnmc.edu/home/student-gateway/accessibility- sas.nmsu.edu resource-center-1/ Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] University of New Mexico (UNM) Western New Mexico University (WNMU) Accessibility Resource Center, Albuquerque, NM Disability Support Services, Silver City, NM 505-277-3506 575-538-6400 as2.unm.edu/ wnmu.edu/specialneeds/contact.shtml Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Questions? Call the CDD Information Network at 1-800-552-8195 or 505-272-8549 www.cdd.unm.edu/infonet More on back The information contained in this document is for general purposes only. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

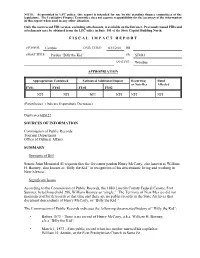

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

Ranching Catalogue

Catalogue Ten –Part Four THE RANCHING CATALOGUE VOLUME TWO D-G Dorothy Sloan – Rare Books box 4825 ◆ austin, texas 78765-4825 Dorothy Sloan-Rare Books, Inc. Box 4825, Austin, Texas 78765-4825 Phone: (512) 477-8442 Fax: (512) 477-8602 Email: [email protected] www.sloanrarebooks.com All items are guaranteed to be in the described condition, authentic, and of clear title, and may be returned within two weeks for any reason. Purchases are shipped at custom- er’s expense. New customers are asked to provide payment with order, or to supply appropriate references. Institutions may receive deferred billing upon request. Residents of Texas will be charged appropriate state sales tax. Texas dealers must have a tax certificate on file. Catalogue edited by Dorothy Sloan and Jasmine Star Catalogue preparation assisted by Christine Gilbert, Manola de la Madrid (of the Autry Museum of Western Heritage), Peter L. Oliver, Aaron Russell, Anthony V. Sloan, Jason Star, Skye Thomsen & many others Typesetting by Aaron Russell Offset lithography by David Holman at Wind River Press Letterpress cover and book design by Bradley Hutchinson at Digital Letterpress Photography by Peter Oliver and Third Eye Photography INTRODUCTION here is a general belief that trail driving of cattle over long distances to market had its Tstart in Texas of post-Civil War days, when Tejanos were long on longhorns and short on cash, except for the worthless Confederate article. Like so many well-entrenched, traditional as- sumptions, this one is unwarranted. J. Evetts Haley, in editing one of the extremely rare accounts of the cattle drives to Califor- nia which preceded the Texas-to-Kansas experiment by a decade and a half, slapped the blame for this misunderstanding squarely on the writings of Emerson Hough. -

History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 82 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2007 Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial Jennifer Nez Denetdale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. "Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial." New Mexico Historical Review 82, 3 (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol82/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival HISTORY, DINE/NAVAJO MEMORY, AND THE BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL Jennifer Nez Denetdale n 4 June 2005, hundreds ofDine and their allies gathered at Fort Sumner, ONew Mexico, to officially open the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Sitting under an arbor, visitors listened to dignitaries interpret the meaning of the Long Walk, explain the four years ofimprisonment at the Bosque Redondo, and discuss the Navajos' return to their homeland in1868. Earlier that morn ing, a small gathering ofDine offered their prayers to the Holy People. l In the past twenty years, historic sites have become popular tourist attrac tions, partially as a result ofpartnerships between state historic preservation departments and the National Park Service. With the twin goals ofeducat ing the public about the American past and promoting their respective states as attractive travel destinations, park officials and public historians have also included Native American sites. -

2020-22 GRADUATE CATALOG | Eastern New Mexico University

2020-22 TABLE OF CONTENTS University Notices..................................................................................................................2 About Eastern New Mexico University ...........................................................................3 About the Graduate School of ENMU ...............................................................................4 ENMU Academic Regulations And Procedures ........................................................... 5 Program Admission .............................................................................................................7 International Student Admission ...............................................................................8 Degree and Non-Degree Classification ......................................................................9 FERPA ................................................................................................................................. 10 Graduate Catalog Graduate Program Academic Regulations and Procedures ......................................................11 Thesis and Non-Thesis Plan of Study ......................................................................11 Graduation ..........................................................................................................................17 Graduate Assistantships ...............................................................................................17 Tuition and Fees ................................................................................................................... -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Women Cattle Drovers Discussion (Oct 1996)

H-Women Women Cattle Drovers Discussion (Oct 1996) Page published by Kolt Ewing on Thursday, June 12, 2014 Women Cattle Drovers Discussion (Oct 1996) Query from Heather Munro Prescott Prescott @ccsua.ctstateu.edu 23 Oct 1996 A student asked me whether it was true that women were used as cattle drivers in the nineteenth century West. I told her I had never heard of this. Is it true? Query X-Posted to H-West Responses: >From Stan Gibson [email protected] 24 Oct 1996 ...I think the answer depends on what is meant by "cattle driving." IMHO, 19c women on the ranges were usually too smart to get entangled in long drives to shipping or sale points--if they did so, they probably were also too smart to boast about it, especially when they were aware of the hardscrabble wages offered. As for the 19c cowmen, there wasn't much reason to note the roles played by their unpaid womenfolks. Moving cattle from summer to winter pasture, and other short drives, however, were undoubtedly common--and probably acceptable--chores for ranchers' wives, daughters, and perhaps even the odd girlfriend. It must have been nice change from heating water on woodstoves, separating and churning, giving birth without nitrous oxide or spinal blocks, and just generally being "useful" back at the ranch. A day or two in the saddle, even today, is fun--and, from my observations recently, still fairly common on western ranches. I have also noted that the well-praised western male courtliness can have its limits, depending on the circumstances. -

The 239 Year Timeline of America's Involvement in Military Conflict

The 239 Year Timeline Of America’s Involvement in Military Conflict By Isaac Davis Region: USA Global Research, December 20, 2015 Theme: History, US NATO War Agenda Activist Post 18 December 2015 I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one. – President Theodore Roosevelt The American public and the world have long since been warned of the dangers of allowing the military industrial complex to become such an integral part of our economic survival. The United States is the self-proclaimed angel of democracy in the world, but just as George Orwell warned, war is the health of the state, and in the language of newspeak, democracy is the term we use to hide the reality of the nature of our warfare state. In truth, the United States of America has been engaged in some kind of war during 218 out of the nation’s total 239 years of existence. Put another way, in the entire span of US history, this country has only experienced 21 years without conflict. For a sense of perspective on this sobering statistic, consider these4 facts about the history of US involvement in military conflict: Pick any year since 1776 and there is about a 91% chance that America was involved in some war during that calendar year. No U.S. president truly qualifies as a peacetime president. Instead, all U.S. presidents can technically be considered “war presidents.” The U.S. has never gone a decade without war. The only time the U.S. went five years without war (1935-40) was during the isolationist period of the Great Depression. -

36 Kansas History DRUNK DRIVING OR DRY RUN?

A Christmas Carol, which appears in Done in the Open: Drawings by Frederick Remington (1902), offers a stereotypical image of the ubiquitous western saloon like those frequented by cowboys at the end of the long drive. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 30 (Spring 2007): 36–51 36 Kansas History DRUNK DRIVING OR DRY RUN? Cowboys and Alcohol on the Cattle Trail by Raymond B. Wrabley Jr. he cattle drive is a central fi xture in the popular mythology of the American West. It has been immortalized—and romanticized—in the fi lms, songs, and literature of our popular culture. It embodies some of the enduring elements of the western story—hard (and dan- gerous) work and play; independence; rugged individualism; cour- Tage; confl ict; loyalty; adversity; cowboys; Indians; horse thieves; cattle rustlers; frontier justice; and the vastness, beauty, and unpredictable bounty and harsh- ness of nature. The trail hand, or cowboy, stands at the interstices of myth and history and has been the subject of immense interest for cultural mythmakers and scholars alike. The cowboy of popular culture is many characters—the loner and the loyal friend; the wide-eyed young boy and the wise, experienced boss; the gentleman and the lout. He is especially the life of the cowtown—the drinker, fi ghter, gambler, and womanizer. Raymond B. Wrabley Jr. received his Ph.D. from Arizona State University and is associate professor of political science at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown, Pennsylvania. The author would like to thank Sara Herr of Pitt-Johnstown’s Owen Library for her efforts in tracking down hard-to-fi nd sources and Richard Slatta for his helpful comments on a draft of the article. -

RED000953.Pdf

IDENTIFICACION Y RECONSTRUCCION DE LA RED DE APOYO A JOSE URREA EN SONORA DURANTE SU CONFLICTO ARMADO CON MANUEL MARIA GANDARA 1837-1845 Tesis que para obtener el grado de Maestro en Ciencias Sociales Línea de investigación: Estudios Históricos de Región y Frontera Presenta Ivan Aarón Torres Chon Directora de Tesis: Dra. Zulema Trejo Contreras Hermosillo, Sonora Febrero del 2011 INTRODUCCION I Planteamiento del problema III CAPITULO I. El SISTEMA DE GOBIERNO FEDERAL. I.1. Balance historiográfico sobre la pugna entre gobierno federalista y centralista. 1 I.2. El pronunciamiento por el federalismo-centralismo en la frontera norte. 5 I.3. José Urrea en la historiografía sonorense. 7 CAPITULO II. ANALISIS DE RED SOCIAL II.1. Análisis de redes en sociología, antropología e historia. 14 II.2 Marco Teórico referencial. 26 CAPITULO III. SONORA EN LA PRIMERA MITAD DEL SIGLO XIX. III.1.Descripción geográfica de Sonora en las décadas de 1830 y 1840. 34 III.2 Principales poblaciones sonorenses. 37 III.2.1 Población general de Sonora. 42 III.2.1.1 Arizpe. 43 III.2.1.2 Horcasitas y Ures. 44 III.2.1.3 Hermosillo. 45 III.2.1.4 Álamos. 46 III.3 Tribus y asentamientos indígenas. 46 III.3.1 Incursiones Apache y sublevaciones indígenas en Sonora. 52 III.4 El intercambio comercial en Sonora en la década de 1830. 54 III.4.1 Agricultura. 55 III.4.2 Ganadería. 56 III.4.3 Minería. 57 III.5 Sistema de gobierno Nacional. 59 III.5.1 Grupos representativos de la política regional. 62 III.5.2 Participación de los militares en la administración estatal. -

Spain's Arizona Patriots in Its 1779-1783 War

W SPAINS A RIZ ONA PA TRIOTS J • in its 1779-1783 WARwith ENGLAND During the AMERICAN Revolutuion ThirdStudy of t he SPANISH B ORDERLA NDS 6y Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough ~~~i~!~~¸~i ~i~,~'~,~'~~'~-~,:~- ~.'~, ~ ~~.i~ !~ :,~.x~: ~S..~I~. :~ ~-~;'~,-~. ~,,~ ~!.~,~~~-~'~'~ ~'~: . Illl ........ " ..... !'~ ~,~'] ." ' . ,~i' v- ,.:~, : ,r~,~ !,1.. i ~1' • ." ~' ' i;? ~ .~;",:I ..... :"" ii; '~.~;.',',~" ,.', i': • V,' ~ .',(;.,,,I ! © Copyright 1999 ,,'~ ;~: ~.~:! [t~::"~ "~, I i by i~',~"::,~I~,!t'.':'~t Granville W. and N.C. Hough 3438 Bahia blanca West, Aprt B Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 k ,/ Published by: SHHAR PRESS Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 http://mcmbers.aol.com/shhar SHHARPres~aol.com (714) $94-8161 ~I,'.~: Online newsletter: http://www.somosprimos.com ~" I -'[!, ::' I ~ """ ~';I,I~Y, .4 ~ "~, . "~ ! ;..~. '~/,,~e~:.~.=~ ........ =,, ;,~ ~c,z;YA':~-~A:~.-"':-'~'.-~,,-~ -~- ...... .:~ .:-,. ~. ,. .... ~ .................. PREFACE In 1996, the authors became aware that neither the NSDAR (National Society for the Daughters of the American Revolution) nor the NSSAR (National Society for the Sons of the American Revolution) would accept descendants of Spanish citizens of California who had donated funds to defray expenses ,-4 the 1779-1783 war with England. As the patriots being turned down as suitable ancestors were also soldiers,the obvious question became: "Why base your membership application on a money contribution when the ancestor soldier had put his life at stake?" This led to a study of how the Spanish Army and Navy had worked during the war to defeat the English and thereby support the fledgling English colonies in their War for Independence. After a year of study, the results were presented to the NSSAR; and that organization in March, 1998, began accepting descendants of Spanish soldiers who had served in California.