History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japan Has Still Yet to Recognize Ryukyu/Okinawan Peoples

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan Prepared for 128th Session, Geneva, 2 March - 27 March, 2020 Submitted by Cultural Survival Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 [email protected] www.culturalsurvival.org International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Alternative Report Submission: Violations of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Japan I. Reporting Organization Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC since 2005. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples’ rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly, and on its website: www.cs.org. II. Introduction The nation of Japan has made some significant strides in addressing historical issues of marginalization and discrimination against the Ainu Peoples. However, Japan has not made the same effort to address such issues regarding the Ryukyu Peoples. Both Peoples have been subject to historical injustices such as suppression of cultural practices and language, removal from land, and discrimination. Today, Ainu individuals continue to suffer greater rates of discrimination, poverty and lower rates of academic success compared to non-Ainu Japanese citizens. Furthermore, the dialogue between the government of Japan and the Ainu Peoples continues to be lacking. The Ryukyu Peoples continue to not be recognized as Indigenous by the Japanese government and face the nonconsensual use of their traditional lands by the United States military. -

American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Approved in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic June 14, 2016 During the Forty-sixth Ordinary Period of Sessions of the OAS General Assembly AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES Organization of American States General Secretariat Secretariat of Access to Rights and Equity Department of Social Inclusion 1889 F Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 | USA 1 (202) 370 5000 www.oas.org ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 More rights for more people OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Organization of American States. General Assembly. Regular Session. (46th : 2016 : Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples : AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) : (Adopted at the thirds plenary session, held on June 15, 2016). p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.P) ; (OAS. Official records ; OEA/ Ser.D) ISBN 978-0-8270-6710-3 1. American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2016). 2. Indigenous peoples--Civil rights--America. 3. Indigenous peoples--Legal status, laws, etc.--America. I. Organization of American States. Secretariat for Access to Rights and Equity. Department of Social Inclusion. II. Title. III. Series. OEA/Ser.P AG/RES.2888 (XLVI-O/16) OEA/Ser.D/XXVI.19 AG/RES. 2888 (XLVI-O/16) AMERICAN DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES (Adopted at the third plenary session, held on June 15, 2016) THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY, RECALLING the contents of resolution AG/RES. 2867 (XLIV-O/14), “Draft American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,” as well as all previous resolutions on this issue; RECALLING ALSO the declaration “Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas” [AG/DEC. -

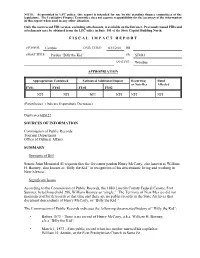

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples of the Pacific

-1- CULTURAL AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF THE PACIFIC Aroha Te Pareake Mead Suva, Fiji 4 September 1996 _____________________________________________________________________ Mr. Chairman, on behalf of Maori Congress I would like to convey to the Prime Minister, the Government and people of Fiji, the Planning Committee, resource people and indigenous participants from throughout Te Moana-Nui-A-Kiwa, our deepest respect. It is indeed a great honour to be invited to participate in this historical regional meeting on the UN Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Before I begin my discussion on cultural and intellectual property rights, I would like to make some brief observations about a few of the issues that were raised at this workshop yesterday. On my first day here in Suva, it was my birthday. My age is reaching a stage where a birthday is not necessarily a celebration anymore, it is more a commemoration, a time for reflection. So on my birthday I reflected on the fact that in the year I was born there were 63 member states in the United Nations. Now, in 1996, there are 185, which means that in my short but ever lengthening life, 122 new countries have realised their right to self-determination, their right to decolonisation and to independence. Nothing in current world events suggests that 185 countries is the final number. Indeed I expect that within the rest of my lifetime, that number will surpass 200 and many of the new states will be indigenous from here in the Pacific basin. This is not a dream it is an inevitable reality. -

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Light of the UN Declaration on The

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Light of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples GUATEMALA Prepared for United Nations Human Rights Council: Universal Periodic Review JANUARY, 2008 CULTURAL SURVIVAL Cultural Survival is an international indigenous rights organization with a global indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of indigenous peoples' rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly; in a newspaper, Voices, that educates indigenous peoples about their rights; and on its website: www.cs.org. In preparing this report, Cultural Survival collaborated with student researchers from Harvard University and consulted with a broad range of indigenous and human rights organizations, advocates, and other sources of verifiable information on Guatemala. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Since the 1996 Peace Accords ended the Guatemalan civil war, the country has made strides to legally recognize the rights of its indigenous peoples and has criminalized racial discrimination. However, political exclusion, discrimination, and economic marginalization of indigenous peoples still regularly occur due to the lack of resources and political will to stop them. Precarious land tenure, delays in land restitution, disproportionately extreme poverty, and geographical remoteness result in indigenous Guatemalans having less access to healthcare, clean water, and security, and lower living standards than the country's Ladino population. Most indigenous children do not have access to bilingual education. Many crimes against indigenous peoples are not investigated or go unpunished; by comparison, indigenous leaders are frequently attacked or prosecuted for defending their claims to their lands. -

Navajo Nation to Obtain an Original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 Document

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2019 Navajo Nation to obtain an original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 document WINDOW ROCK – Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer are pleased to announce the generous donation of one of three original Navajo Treaty of 1868, also known as Naaltsoos Sání, documents to the Navajo Nation. On June 1, 1868, three copies of the Treaty of 1868 were issued at Fort Sumner, N.M. One copy was presented to the U.S. Government, which is housed in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington D.C. The second copy was given to Navajo leader Barboncito – its current whereabouts are unknown. The third unsigned copy was presented to the Indian Peace Commissioner, Samuel F. Tappan. The original document is also known as the “Tappan Copy” is being donated to the Navajo Nation by Clare “Kitty” P. Weaver, the niece of Samuel F. Tappan, who was the Indian Peace Commissioner at the time of the signing of the treaty in 1868. “On behalf of the Navajo Nation, it is an honor to accept the donation from Mrs. Weaver and her family. The Naaltsoos Sání holds significant cultural and symbolic value to the Navajo people. It marks the return of our people from Bosque Redondo to our sacred homelands and the beginning of a prosperous future built on the strength and resilience of our people,” said President Nez. Following the signing of the Treaty of 1868, our Diné people rebuilt their homes, revitalized their livestock and crops that were destroyed at the hands of the federal government, he added. -

Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Thanks to the New Mexico Humanities Council and the Western National Parks and Monuments Association for their important contributions to this study. DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Apache, Coconino, Navajo Counties, Arizona; Bernalillo, Cibola, De Baca, Guadalupe, Lincoln, McKinley, Mora, Otero, Santa Fe, Sandoval, Torrance, Valencia Counties, New Mexico The purpose of this study is to evaluate the suitability and feasibility of designating the routes known as the “Long Walk” of the Mescalero Apache and the Navajo people (1862-1868) as a national historic trail under the study provisions of the National Trails System Act (Public Law 90-543). This study provides necessary information for evaluating the national significance of the Long Walk, which refers to the U.S. Army’s removal of the Mescalero Apache and Navajo people from their homelands to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in eastern New Mexico, and for potential designation of a national historic trail. Detailed administrative recommendations would be developed through the subsequent preparation of a comprehensive management plan if a national historic trail is designated. The three criteria for national historic trails, as defined in the National Trails System Act, have been applied and have been met for the proposed Long Walk National Historic Trail. The trail routes possess a high degree of integrity and significant potential for historical interest based on historic interpretation and appreciation. -

Genocide, Ethnocide, Ecocide, with Special Reference to Indigenous Peoples: a Bibliography

Genocide, Ethnocide, Ecocide, with Special Reference to Indigenous Peoples: A Bibliography Robert K. Hitchcock Department of Anthropology and Geography University of Nebraska-Lincoln Lincoln, NE 68588-0368 [email protected] Adalian, Rouben (1991) The Armenian Genocide: Context and Legacy. Social Education 55(2):99-104. Adalian, Rouben (1997) The Armenian Genocide. In Century of Genocide: Eyewitness Accounts and Critical Views, Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons and Israel W. Charny eds. Pp. 41-77. New York and London: Garland Publishing Inc. Adams, David Wallace (1995) Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875-1928. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. Africa Watch (1989) Zimbabwe, A Break with the Past? Human Rights and Political Unity. New York and Washington, D.C.: Africa Watch Committee. Africa Watch (1990) Somalia: A Government at War With Its Own People. Testimonies about the Killings and the Conflict in the North. New York, New York: Human Rights Watch. African Rights (1995a) Facing Genocide: The Nuba of Sudan. London: African Rights. African Rights (1995b) Rwanda: Death, Despair, and Defiance. London: African Rights. African Rights (1996) Rwanda: Killing the Evidence: Murders, Attacks, Arrests, and Intimidation of Survivors and Witnesses. London: African Rights. Albert, Bruce (1994) Gold Miners and Yanomami Indians in the Brazilian Amazon: The Hashimu Massacre. In Who Pays the Price? The Sociocultural Context of Environmental Crisis, Barbara Rose Johnston, ed. pp. 47-55. Washington D.C. and Covelo, California: Island Press. Allen, B. (1996) Rape Warfare: The Hidden Genocide in Bosnia-Herzogovina and Croatia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. American Anthropological Association (1991) Report of the Special Commission to Investigate the Situation of the Brazilian Yanomami, June, 1991. -

Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 10-2-1909 Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub. Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news Recommended Citation Review Pub. Co.. "Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news/9 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lie rort Sumner Review VOL 2--- 12. FORT SUMNER, (Sunnyside Post office), GUADALUPE COUNTY, N. M., OCTOBER 2, 1909. $1 A YEAR, CASH. JL Murder of Miss Hattonl. Thc !oenf of the ,imeis with-- ! The Small Holding . in a mue or aanta Kosa, among ; LOCALETTES i I at Santa Rosa. ' the hilla overlooking the city, Claims. and while wild, yet the roitd (Special Correspondence. ) within a short distance is much AU persons who are .claiming Rosa, N M, Sept. 27- .- land because they have lived on Our Invitation George B. Deen, wife, and Santa traveled. Miss 18, the same for years little son, were called to Portales Sarah Hatton, daughter Miss Hatton was a beautiful twent' or Mrs. R. I. young i more, these claims 'being com- - Tuesday to attend the funeral of Mr. and Hatton of lady, a leader among the of a little nephew. Los Tanos, a small station on the young folks of her town and had monly kno.wn as "small holding Rack Island, nine miles east of many friends here. -

Guide to the Museum

Join Us in Supporting History! Become a Member of the Kit Carson Home and Museum! It is not an easy task to preserve America’s historic treasures! The Kit Carson Home in Taos is a designated National Landmark, but the Museum receives no federal or state support. We depend on members and donors to help us preserve the site and keep it open to the public. The Kit Carson Home was important in the history of the American Southwest. Please join us in our efforts to preserve it by becoming a Friend of the KCHM today! Senior/Student $20 Individual $35 Corporate $45 GUIDE TO THE MUSEUM Donor $100 - 499 Christopher (Kit) Carson was one of the most dramatic and Patron $500 - 999 Lifetime controversial characters of the American West. He was a trapper, scout, and rancher, officer in the United States Army, transcontinental Other Donation _____________________________________ courier and U.S. Indian agent. Carson was instrumental in discovering the passageway to the Pacific Ocean. He was a rugged frontiersman All memberships include a membership card, free admission to the who understood the ways of tribal Native America. A true enigma, Museum, notice of upcoming events and The Carson Courier, the Carson remains to this day a revered yet misunderstood historical Museum’s semi-annual newsletter. figure. Yes! I want to be a member! I will pay by: _____check Modern biographers portray Carson as a complex and enigmatic man _____cash who participated in many of the major historical events of America’s _____credit card (please call the Museum to pay via cc) westward expansion. -

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in the Democratic Republic of Congo Prepared for: The 33rd Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review February 2019 Submission date: October 2018 Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC since 2005. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous Peoples' rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly; and on its website: www.cs.org. Cultural Survival also produces and distributes quality radio programs that strengthen and sustain Indigenous languages, cultures, and civil participation. Submitted by Cultural Survival Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 [email protected] www.culturalsurvival.org Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Democratic Republic of Congo I. Background Information Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) has experienced instability and conflict throughout much of its independence since 1960. There has been a resurgence of violence particularly in the east of the country, despite a peace agreement signed with the National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), a primarily Tutsi rebel group. An attempt to integrate CNDP members into the Congolese military failed, prompting their defection in 2012 and the formation of the M23 armed group, and led to continuous conflict causing the displacement of large populations and human rights abuses before the M23 was pushed out of DRC to Uganda and Rwanda in late 2013 by a joint DRC and UN offensive. -

Reclaiming Spaces Between: Coast Salish Two Spirit Identities and Experiences

Reclaiming Spaces Between: Coast Salish Two Spirit Identities and Experiences by Corrina Sparrow Bachelor of Social Work, University of Victoria, 2006 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK in the School of Social Work Corrina Sparrow, 2018 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Reclaiming Spaces Between: Coast Salish Two Spirit Identities and Experiences by Corrina Sparrow Bachelor of Social Work - Indigenous, University of Victoria, 2006 Supervisory Committee Dr. Billie Allan, School of Social Work Supervisor Dr. Robina Thomas, School of Social Work Co-Supervisor iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Billie Allan, School of Social Work Supervisor Dr. Robina Thomas, School of Social Work Co-Supervisor The seed for this research germinated deep in the lands of our Coast Salish ancestors thousands of years ago. As a Coast Salish Two Spirit researcher, I noticed there is a striking absence of west coast Indigenous and Coast Salish specific knowledge about Two Spirit identities, experiences and vision work in academic and community circles. Therefore, this research was conducted exclusively on Coast Salish territories, with Coast Salish identified Two Spirit participants and allies. I apply my Four House Posts Coast Salish methodology in an Indigenous research framework, and through storytelling and art-based methods, this study asks - How does recognition of Coast Salish Two Spirit identity and experience contribute to community wellness and cultural resurgence? The intention of this study is to offer pathways for intergenerational healing and reconnections, cultural revitalization and transformation by weaving traditional Indigenous knowledges with contemporary narratives, in order to increase voice and visibility of Coast Salish Two Spirit People.