Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Environmental History of the Middle Rio Grande Basin

United States Department of From the Rio to the Sierra: Agriculture Forest Service An Environmental History of Rocky Mountain Research Station the Middle Rio Grande Basin Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5 Dan Scurlock i Scurlock, Dan. 1998. From the rio to the sierra: An environmental history of the Middle Rio Grande Basin. General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-5. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 440 p. Abstract Various human groups have greatly affected the processes and evolution of Middle Rio Grande Basin ecosystems, especially riparian zones, from A.D. 1540 to the present. Overgrazing, clear-cutting, irrigation farming, fire suppression, intensive hunting, and introduction of exotic plants have combined with droughts and floods to bring about environmental and associated cultural changes in the Basin. As a result of these changes, public laws were passed and agencies created to rectify or mitigate various environmental problems in the region. Although restoration and remedial programs have improved the overall “health” of Basin ecosystems, most old and new environmental problems persist. Keywords: environmental impact, environmental history, historic climate, historic fauna, historic flora, Rio Grande Publisher’s Note The opinions and recommendations expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDA Forest Service. Mention of trade names does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the Federal Government. The author withheld diacritical marks from the Spanish words in text for consistency with English punctuation. Publisher Rocky Mountain Research Station Fort Collins, Colorado May 1998 You may order additional copies of this publication by sending your mailing information in label form through one of the following media. -

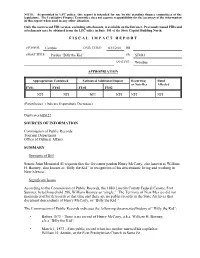

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 82 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2007 Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial Jennifer Nez Denetdale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. "Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial." New Mexico Historical Review 82, 3 (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol82/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival HISTORY, DINE/NAVAJO MEMORY, AND THE BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL Jennifer Nez Denetdale n 4 June 2005, hundreds ofDine and their allies gathered at Fort Sumner, ONew Mexico, to officially open the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Sitting under an arbor, visitors listened to dignitaries interpret the meaning of the Long Walk, explain the four years ofimprisonment at the Bosque Redondo, and discuss the Navajos' return to their homeland in1868. Earlier that morn ing, a small gathering ofDine offered their prayers to the Holy People. l In the past twenty years, historic sites have become popular tourist attrac tions, partially as a result ofpartnerships between state historic preservation departments and the National Park Service. With the twin goals ofeducat ing the public about the American past and promoting their respective states as attractive travel destinations, park officials and public historians have also included Native American sites. -

Constitution of the Zuni Tribe, Zuni Reservation, Zuni, New Mexico

CONSTITUTION OF THE ZUNI TRIBE ZUNI RESERVATION, ZUNI, NEW MEXICO PREAMBLE We, the members of the Zuni Tribe, Zuni Indian Reservation, New Mexico, in order to secure to us and to our posterity the political and civil rights guaranteed to us by treaties and by the Constitution and statutes of the United States; to secure educational advantage; to encourage good citizenship; to exercise the right of self-government; to administer both as a municipal body and as a proprietor of our tribal affairs; to utilize, increase and protect our tribal resources; to encourage and promote all movements and efforts leading to the general welfare of our tribe; to guarantee individual rights and freedom of religion; and to maintain our tribal customs and traditions; do ordain and establish this constitution. ARTICLE I – JURISDICTION The jurisdiction of the Zuni Tribe, Zuni Indian Reservation exercised through the Zuni Tribal Council, the Executive Department and the Judicial Department, acting in accordance with this constitution and the ordinances adopted in accordance herewith, shall extend to all tribal lands included within the present boundaries of the Zuni Indian Reservation and to such other lands as may hereafter be added thereto, unless otherwise provided by law. This jurisdiction shall apply to and be for the benefit and protection of all Indians who now, or may in the future, reside on the Zuni Reservation. The name of this organization shall be the Zuni Tribe. ARTICLE II – MEMBERSHIP Section 1. The membership of the Zuni Tribe, Zuni Indian Reservation, shall consist of the following: a. All persons enrolled on the Zuni Agency census roll of April 1, 1963; provided that the roll may be corrected at any time by the tribal council, subject to the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. -

Scenic Trips to the Geologic Past No. 4: Southern Zuni Mountains. Zuni

SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST No. No. 1—Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1968 ($1.00). No. 2—Taos-Red River-Eagle Nest, New Mexico, Circle Drive 1968 ($1.00). No. 3—Roswell-Capitan-Ruidoso and Bottomless Lakes Park, New Mexico, 1967 ($1.00). No. 4—Southern Zuni Mountains, New Mexico, 1971 ($1.50). No. No. 5—Silver City-Santa Rita-Hurley, New Mexico, 1967 ($1.00). No. 6—Trail Guide to the Upper Pecos, New Mexico, 1967 ($1.50). No. 7—High Plains—Northeastern New Mexico, Raton-Capulin Mountain- Clayton, 1967 ($1.50). No. 8—Mosaic of New Mexico's Scenery, Rocks, and History, 1967 ($1.50). No. 9—Albuquerque-Its Mountains, valley, Water, and Volcanoes, 1969 ($1.50). No. 10—Southwestern New Mexico, 1971 ($1.50). Cover: SHALAKO WARRIOR DOLL “Man-made highways and automobiles crisscross this world but hardly penetrate it…” J. FRANK DOBIE Apache Gold and Yaqui Silver SCENIC TRIPS TO THE GEOLOGIC PAST NO. 4 Southern Zuni Mountains Zuni-Cibola Trail BY ROY W. FOSTER PHOTOGRAPHS BY H. L. JAMES SKETCHES BY PATRICIA C. GICLAS 1971 STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY CAMPUS STATION SOCORRO, NEW MEXICO 87801 NEW MEXICO STATE BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERAL RESOURCES DON H. BAKER, JR., Director A Division of NEW MEXICO INSTITUTE OF MINING AND TECHNOLOGY STIRLING A. COLGATE, President THE REGENTS MEMBERS EX OFFICIO The Honorable Bruce King ...............................Governor of New Mexico Leonard DeLayo .............................Superintendent of Public Instruction APPOINTED MEMBERS William G. Abbott .......................................................................... Hobbs Henry S. Birdseye ................................................................Albuquerque Ben Shantz ................................................................................Silver City Steve S. -

Triassic Stratigraphy of the Southeastern Colorado Plateau, West-Central New Mexico Spencer G

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: https://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/72 Triassic stratigraphy of the southeastern Colorado Plateau, west-central New Mexico Spencer G. Lucas, 2021, pp. 229-240 in: Geology of the Mount Taylor area, Frey, Bonnie A.; Kelley, Shari A.; Zeigler, Kate E.; McLemore, Virginia T.; Goff, Fraser; Ulmer-Scholle, Dana S., New Mexico Geological Society 72nd Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 310 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 2021 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, Color Plates, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Geology and Coal Resources of Atarque Lake Quadrangle, Cibola

GEOLOGY AND COAL RESOURCESOF THE ATARQUE LAKEQUADRANGLE, CIBOLA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF MINES AND MINERALRESOURCES OPEN-FILEREPORT 167 bY ORIN J. ANDERSON June, 1982 (revised,1983) Contents: (1) Discussion of Geology and CoalResources (attached) (2) Geologic map with cross sesction (accompanying) Table of Contents GEOLOGY General P. Study Area P. Structure P. Stratigraphy P. COAL RESOURCES p. 22 REFERENCES p. 23 Figures 1 - Measured section of Zuni and Dakota SS. p. 11 2 - Measured section of Atarque and Moreno Hill Fms. p. 18 GEOLOGY General The Atarque Lake quadrangle lies in the southwestern part of the Zuni Basin, a broad,shallow structural element that extends southwestward from the Zuni Mountains of New Mexico into east- central Arizona. As such it liesnear the southeastern margin ofthe Colorado Plateau. The regionaldip in the study area is very gently northeastward toward the Gallup Sag which comprises thenortheastern part of the Basin. There are, however, broad, gentle NW-SE trending folds which result in local southwestward dips, and at least twoabrupt monoclinal flexures, up on the northeastside, (opposed to regional dip) that clearly define the NW-SE structural grain of the area, as well as minor faulting. These structural trends parallel the axis of the Zuni Uplift, but perhaps more importantly they appear to represent the southeastward extension of the structural axes that wrap aroundthe southern end of the Defiance Uplift, as shown by Davis andKiven (1975), and theyalso align very well with the northwest-trendingdike system in the Fence Lake (the Dyke quadrangle),Techado, Adams Diggings,and Pietown areas. Of the three structural features mentioned - broadfolds, monoclines and faulting - monoclinesare the most pronounced and significantnot only locally, but in a much broadercontext. -

Cenozoic Thermal, Mechanical and Tectonic Evolution of the Rio Grande Rift

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 91, NO. B6, PAGES 6263-6276, MAY 10, 1986 Cenozoic Thermal, Mechanical and Tectonic Evolution of the Rio Grande Rift PAUL MORGAN1 Departmentof Geosciences,Purdue University,West Lafayette, Indiana WILLIAM R. SEAGER Departmentof Earth Sciences,New Mexico State University,Las Cruces MATTHEW P. GOLOMBEK Jet PropulsionLaboratory, CaliforniaInstitute of Technology,Pasadena Careful documentationof the Cenozoicgeologic history of the Rio Grande rift in New Mexico reveals a complexsequence of events.At least two phasesof extensionhave been identified.An early phase of extensionbegan in the mid-Oligocene(about 30 Ma) and may have continuedto the early Miocene (about 18 Ma). This phaseof extensionwas characterizedby local high-strainextension events (locally, 50-100%,regionally, 30-50%), low-anglefaulting, and the developmentof broad, relativelyshallow basins, all indicatingan approximatelyNE-SW •-25ø extensiondirection, consistent with the regionalstress field at that time.Extension events were not synchronousduring early phase extension and were often temporally and spatiallyassociated with major magmatism.A late phaseof extensionoccurred primarily in the late Miocene(10-5 Ma) with minor extensioncontinuing to the present.It was characterizedby apparently synchronous,high-angle faulting givinglarge verticalstrains with relativelyminor lateral strain (5-20%) whichproduced the moderuRio Granderift morphology.Extension direction was approximatelyE-W, consistentwith the contemporaryregional stress field. Late phasegraben or half-grabenbasins cut and often obscureearly phasebroad basins.Early phase extensionalstyle and basin formation indicate a ductilelithosphere, and this extensionoccurred during the climax of Paleogenemagmatic activity in this zone.Late phaseextensional style indicates a more brittle lithosphere,and this extensionfollowed a middle Miocenelull in volcanism.Regional uplift of about1 km appearsto haveaccompanied late phase extension, andrelatively minor volcanism has continued to thepresent. -

Gravity and Aeromagnetic Studies of the Santo Domingo Basin Area, New Mexico

Gravity and Aeromagnetic Studies of the Santo Domingo Basin Area, New Mexico By V.J.S. Grauch, David A. Sawyer, Scott A. Minor, Mark R. Hudson, and Ren A. Thompson Chapter D of The Cerrillos Uplift, the La Bajada Constriction, and Hydrogeologic Framework of the Santo Domingo Basin, Rio Grande Rift, New Mexico Edited by Scott A. Minor Professional Paper 1720–D U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Abstract .........................................................................................................................................................63 Introduction...................................................................................................................................................63 Gravity Data and Methods..........................................................................................................................64 Data Compilation .................................................................................................................................64 Estimating Thickness of Basin Fill ...................................................................................................64 Locating Faults From Gravity Data ...................................................................................................66 Aeromagnetic Data and Methods .............................................................................................................69 Data Compilation .................................................................................................................................69 -

Navajo Nation to Obtain an Original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 Document

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2019 Navajo Nation to obtain an original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 document WINDOW ROCK – Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer are pleased to announce the generous donation of one of three original Navajo Treaty of 1868, also known as Naaltsoos Sání, documents to the Navajo Nation. On June 1, 1868, three copies of the Treaty of 1868 were issued at Fort Sumner, N.M. One copy was presented to the U.S. Government, which is housed in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington D.C. The second copy was given to Navajo leader Barboncito – its current whereabouts are unknown. The third unsigned copy was presented to the Indian Peace Commissioner, Samuel F. Tappan. The original document is also known as the “Tappan Copy” is being donated to the Navajo Nation by Clare “Kitty” P. Weaver, the niece of Samuel F. Tappan, who was the Indian Peace Commissioner at the time of the signing of the treaty in 1868. “On behalf of the Navajo Nation, it is an honor to accept the donation from Mrs. Weaver and her family. The Naaltsoos Sání holds significant cultural and symbolic value to the Navajo people. It marks the return of our people from Bosque Redondo to our sacred homelands and the beginning of a prosperous future built on the strength and resilience of our people,” said President Nez. Following the signing of the Treaty of 1868, our Diné people rebuilt their homes, revitalized their livestock and crops that were destroyed at the hands of the federal government, he added. -

U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Prepared in cooperation with New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources 1997 MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Cover: View looking south to the east side of the northeastern Organ Mountains near Augustin Pass, White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico. Town of White Sands in distance. (Photo by Susan Bartsch-Winkler, 1995.) MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO By SUSAN BARTSCH-WINKLER, Editor ____________________________________________________ U. S GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OPEN-FILE REPORT 97-521 U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources, Socorro U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Mark Shaefer, Interim Director For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Service Center Box 25286, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government MINERAL AND ENERGY RESOURCES OF THE MIMBRES RESOURCE AREA IN SOUTHWESTERN NEW MEXICO Susan Bartsch-Winkler, Editor Summary Mimbres Resource Area is within the Basin and Range physiographic province of southwestern New Mexico that includes generally north- to northwest-trending mountain ranges composed of uplifted, faulted, and intruded strata ranging in age from Precambrian to Recent. -

Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 10-2-1909 Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub. Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news Recommended Citation Review Pub. Co.. "Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news/9 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lie rort Sumner Review VOL 2--- 12. FORT SUMNER, (Sunnyside Post office), GUADALUPE COUNTY, N. M., OCTOBER 2, 1909. $1 A YEAR, CASH. JL Murder of Miss Hattonl. Thc !oenf of the ,imeis with-- ! The Small Holding . in a mue or aanta Kosa, among ; LOCALETTES i I at Santa Rosa. ' the hilla overlooking the city, Claims. and while wild, yet the roitd (Special Correspondence. ) within a short distance is much AU persons who are .claiming Rosa, N M, Sept. 27- .- land because they have lived on Our Invitation George B. Deen, wife, and Santa traveled. Miss 18, the same for years little son, were called to Portales Sarah Hatton, daughter Miss Hatton was a beautiful twent' or Mrs. R. I. young i more, these claims 'being com- - Tuesday to attend the funeral of Mr. and Hatton of lady, a leader among the of a little nephew. Los Tanos, a small station on the young folks of her town and had monly kno.wn as "small holding Rack Island, nine miles east of many friends here.