Restocking the Navajo Reservation After the Bosque Redondo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navajo Baskets and the American Indian Voice: Searching for the Contemporary Native American in the Trading Post, the Natural History Museum, and the Fine Art Museum

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-07-18 Navajo Baskets and the American Indian Voice: Searching for the Contemporary Native American in the Trading Post, the Natural History Museum, and the Fine Art Museum Laura Paulsen Howe Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Art Practice Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Howe, Laura Paulsen, "Navajo Baskets and the American Indian Voice: Searching for the Contemporary Native American in the Trading Post, the Natural History Museum, and the Fine Art Museum" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 988. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. by Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Brigham Young University All Rights Reserved BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. ________________________ ______________________________________ Date ________________________ ______________________________________ Date ________________________ ______________________________________ Date BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY As chair of the candidate’s graduate committee, I have read the format, citations and bibliographical -

The Navajo Creation Story and Modern Tribal Justice

Tribal Law Journal Volume 15 Volume 15 (2014-2015) Article 2 1-1-2014 She Saves Us from Monsters: The Navajo Creation Story and Modern Tribal Justice Heidi J. Todacheene University of New Mexico - School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/tlj Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Todacheene, Heidi J.. "She Saves Us from Monsters: The Navajo Creation Story and Modern Tribal Justice." Tribal Law Journal 15, 1 (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/tlj/vol15/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tribal Law Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. SHE SAVES US FROM MONSTERS: THE NAVAJO CREATION STORY AND MODERN TRIBAL JUSTICE Heidi J. Todacheene After we get back to our country it will brighten up again and the Navajos will be as happy as the land, black clouds will rise and there will be plenty of rain. –Barboncito, 1868 Introduction Traditional Navajos believe the Diné Bahane’1 or the “Navajo creation story” and journey narrative was given to the Navajo people by the Holy Beings. Changing Woman is the Holy Being that created the four original clans of the Navajo and saved humans from the monsters that were destroying the earth. The Navajo tribe is matrilineal because Changing Woman created the clan system in the creation story. -

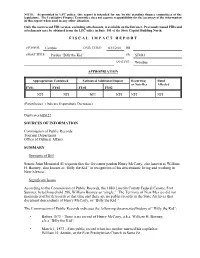

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 82 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2007 Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial Jennifer Nez Denetdale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. "Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial." New Mexico Historical Review 82, 3 (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol82/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival HISTORY, DINE/NAVAJO MEMORY, AND THE BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL Jennifer Nez Denetdale n 4 June 2005, hundreds ofDine and their allies gathered at Fort Sumner, ONew Mexico, to officially open the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Sitting under an arbor, visitors listened to dignitaries interpret the meaning of the Long Walk, explain the four years ofimprisonment at the Bosque Redondo, and discuss the Navajos' return to their homeland in1868. Earlier that morn ing, a small gathering ofDine offered their prayers to the Holy People. l In the past twenty years, historic sites have become popular tourist attrac tions, partially as a result ofpartnerships between state historic preservation departments and the National Park Service. With the twin goals ofeducat ing the public about the American past and promoting their respective states as attractive travel destinations, park officials and public historians have also included Native American sites. -

Diné Binaadââ' Ch'iyáán Traditional Navajo Corn Recipes

Sà’ah Nagháí Bik’eh Hózhóón Dinétah since 1996 Catalog 2016 – 2017 Naadàà’ Ãees’áán Dootã’izhí Blue Corn Bread Sà’ah Nagháí Bik’eh Hózhóón New Diné Binaadââ’ Ch’iyáán Traditional Navajo Corn Recipes www.nativechild.com PO Box 30456 Flagstaff, AZ 86003 voice 505 820 2204 fax 480 559 8626 [email protected] Bilingual Units Item No Quantity Title Amount 1008 Colors paper edition $ 19.80 1009 Colors card stock edition $ 29.80 2001 24 Shapes paper edition $ 29.80 2002 24 Shapes card stock edition $ 45.00 1003 Feelings paper edition $ 17.80 1004 Feelings card stock edition $ 25.80 1113 Numbers paper edition $ 27.80 1114 Numbers + activities card stock edition $ 37.80 2004 35 Diné Letters: Photo edition card stock in binder $ 65.00 6017 35 Diné Letters: Photo edition laminated, boxed version $ 69.95 2018 Food 70 Photos paper edition $ 89.00 2019 Food 70 Photos card stock edition $ 125.00 2005 50 Animals paper edition $ 65.00 2006 50 Animals card stock edition $ 98.00 2030 60 Plants from Navajoland paper edition $ 78.00 2031 60 Plants from Navajoland card stock edition $ 114.00 2040 50 Traditional Diné items paper edition $ 65.00 2041 50 Traditional Diné items card stock edition $ 98.00 6001 Transportation/Money paper edition $ 29.50 6002 Transportation/Money card stock edition $ 45.00 6005 Nature 35 photos paper edition $ 48.00 6006 Nature 35 photos card stock edition $ 69.00 6015 50 Insects and Spiders paper edition $ 65.00 6016 50 Insects and Spiders card stock edition $ 98.00 6018 50 Birds of Navajoland paper edition $ 65.00 6019 50 Birds of Navajoland card stock edition $ 98.00 Please add 10% to cover FEDEX Shipping and Handling The material is organized in deluxe three ring binders for convenient use and storage. -

Navajo Nation to Obtain an Original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 Document

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2019 Navajo Nation to obtain an original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 document WINDOW ROCK – Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer are pleased to announce the generous donation of one of three original Navajo Treaty of 1868, also known as Naaltsoos Sání, documents to the Navajo Nation. On June 1, 1868, three copies of the Treaty of 1868 were issued at Fort Sumner, N.M. One copy was presented to the U.S. Government, which is housed in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington D.C. The second copy was given to Navajo leader Barboncito – its current whereabouts are unknown. The third unsigned copy was presented to the Indian Peace Commissioner, Samuel F. Tappan. The original document is also known as the “Tappan Copy” is being donated to the Navajo Nation by Clare “Kitty” P. Weaver, the niece of Samuel F. Tappan, who was the Indian Peace Commissioner at the time of the signing of the treaty in 1868. “On behalf of the Navajo Nation, it is an honor to accept the donation from Mrs. Weaver and her family. The Naaltsoos Sání holds significant cultural and symbolic value to the Navajo people. It marks the return of our people from Bosque Redondo to our sacred homelands and the beginning of a prosperous future built on the strength and resilience of our people,” said President Nez. Following the signing of the Treaty of 1868, our Diné people rebuilt their homes, revitalized their livestock and crops that were destroyed at the hands of the federal government, he added. -

Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Thanks to the New Mexico Humanities Council and the Western National Parks and Monuments Association for their important contributions to this study. DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Apache, Coconino, Navajo Counties, Arizona; Bernalillo, Cibola, De Baca, Guadalupe, Lincoln, McKinley, Mora, Otero, Santa Fe, Sandoval, Torrance, Valencia Counties, New Mexico The purpose of this study is to evaluate the suitability and feasibility of designating the routes known as the “Long Walk” of the Mescalero Apache and the Navajo people (1862-1868) as a national historic trail under the study provisions of the National Trails System Act (Public Law 90-543). This study provides necessary information for evaluating the national significance of the Long Walk, which refers to the U.S. Army’s removal of the Mescalero Apache and Navajo people from their homelands to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in eastern New Mexico, and for potential designation of a national historic trail. Detailed administrative recommendations would be developed through the subsequent preparation of a comprehensive management plan if a national historic trail is designated. The three criteria for national historic trails, as defined in the National Trails System Act, have been applied and have been met for the proposed Long Walk National Historic Trail. The trail routes possess a high degree of integrity and significant potential for historical interest based on historic interpretation and appreciation. -

Navajo N a Lion Scholarship and Financial Assistance

The Department of Dine Education Off;ce o/ Navajo N a lion Scholarship and Financial Assistance P.O. Box 1870 Window Rock, AZ. 86515 (928) 871-7444, 1-800-243-2956, WWW.Onnsfa.org llen D. Yazzie was one of que for high school. In 1942, Allen Athe first Navajo students was drafted. While in the Army, to receive a Bachelor's he saw Africa, Sicily, France, and Degree in Education from Alizona Italy. When he came home, he State College in Flagstaff, Arizona. enrolled in college. Back then , stu It was 1953. dents received $1,200. At the time, When he was eight years the Navajo Nation Scholarship old in 1925 Steamboat, A1izona, policy stated, "Recipients of aid his father, Deneb, was prepar- from said funds shall be members ing him for an entirely different of the Navajo Tribe at least one future - to be a medicine man half Indian Blood, shall be gradu teaching him Navajo ceremonies ates of high schools, and shall be and songs. Coming from a family chosen on the basis of previous of six children, he was also needed scholastic achievement, personal at home to herd sheep and plant ity, characte1; general premise, and the com fields. He twice asked his ability." ONNSFA Staff (l-R): Rowena Becenti, Carol Yazzie, leon Curtis, Grace father to let him go to school ; twice Today, the Office of Navajo Cooley, Maxine Damon, Kay Nave-Mark, l ena Joe, Winona Kay, Eltavisa Begay, Shirley Tunney, Orlinda Brown, Rose Graham, and Ang~la Gilmore. his father said no. Asking a th ird Nation Scholarship and Financial time, Allen was told, "It's up to Assistance is still dedicated to classes, as well as our own local and foremost, who took the time your mom." She consented. -

Navajo Indians of the Southwest History Worksheets

Navajo Indians of the Southwest Americans built a fort, named Fort Defiance in Navajo territory in September 1851. The Americans seized the valuable grazing land around the fort. In 1860, when the Navajo’s livestock strayed onto pastures, U.S. soldiers slaughtered a number of Navajo horses. The Navajos raided army herds in order to replenish their losses. The Navajo eventually led two attacks against the fort, one in 1856 and one in 1860. Nearly 1,000 Navajo warriors attacked the Fort in the 1860 raid, but Maneulito (below right) and Barboncito (right) did not have enough weapons to take the fort. Navajo continued their hit and run attacks. A militia unit, the Second New Mexico Mounted Volunteers, was formed to fight the Navajos and Apaches. In January 1861, Maneulito and other leaders met with Colonel Canby to sign a new peace treaty. The Navajo were anxious to get back to their crops and livestock and signed the treaty. A second fort, called Fort Fauntleroy, was built in 1860. (Later it was renamed Fort Wingate.) Manuel Chaves became the commander of the fort. The Navajo gathered at the fort for rations and friendly horse races. There had been heavy betting. Allegations of cheating in a horse race led to a fight between Chaves’s men and visiting Navajos. Chaves ordered his men to fire at the Navajo. In all, the troops killed twelve Navajo men, women, and children and wounded around forty more. In 1862, Fort Wingate was moved. The Civil War was in full swing. Navajo raids increased. Citizens in the area complained that nearly 30,000 sheep were stolen in 1862. -

Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 10-2-1909 Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub. Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news Recommended Citation Review Pub. Co.. "Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news/9 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lie rort Sumner Review VOL 2--- 12. FORT SUMNER, (Sunnyside Post office), GUADALUPE COUNTY, N. M., OCTOBER 2, 1909. $1 A YEAR, CASH. JL Murder of Miss Hattonl. Thc !oenf of the ,imeis with-- ! The Small Holding . in a mue or aanta Kosa, among ; LOCALETTES i I at Santa Rosa. ' the hilla overlooking the city, Claims. and while wild, yet the roitd (Special Correspondence. ) within a short distance is much AU persons who are .claiming Rosa, N M, Sept. 27- .- land because they have lived on Our Invitation George B. Deen, wife, and Santa traveled. Miss 18, the same for years little son, were called to Portales Sarah Hatton, daughter Miss Hatton was a beautiful twent' or Mrs. R. I. young i more, these claims 'being com- - Tuesday to attend the funeral of Mr. and Hatton of lady, a leader among the of a little nephew. Los Tanos, a small station on the young folks of her town and had monly kno.wn as "small holding Rack Island, nine miles east of many friends here. -

Report No. 211/20

OEA/Ser.L/V/II REPORT No. 211 /20 Doc. 225 August 24, 2020 CASE 13.570 Original: English REPORT ON ADMISSIBILITY AND MERITS (PUBLICATION) LEZMOND C. MITCHELL UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Approved electronically by the Commission on August 24, 2020. Cite as: IACHR, Report No. 211 /20. Case 13.570. Admissibility and Merits (Publication). Lezmond C. Mitchell. United States of America. August 24, 2020. www.iachr.org INDEX I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 II. POSITIONS OF THE PARTIES .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 A. Petitioners ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 B. State ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 III. ADMISSIBILITY................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 A. Competence, duplication of procedures and international res judicata .......................................................................... -

Guide to the Museum

Join Us in Supporting History! Become a Member of the Kit Carson Home and Museum! It is not an easy task to preserve America’s historic treasures! The Kit Carson Home in Taos is a designated National Landmark, but the Museum receives no federal or state support. We depend on members and donors to help us preserve the site and keep it open to the public. The Kit Carson Home was important in the history of the American Southwest. Please join us in our efforts to preserve it by becoming a Friend of the KCHM today! Senior/Student $20 Individual $35 Corporate $45 GUIDE TO THE MUSEUM Donor $100 - 499 Christopher (Kit) Carson was one of the most dramatic and Patron $500 - 999 Lifetime controversial characters of the American West. He was a trapper, scout, and rancher, officer in the United States Army, transcontinental Other Donation _____________________________________ courier and U.S. Indian agent. Carson was instrumental in discovering the passageway to the Pacific Ocean. He was a rugged frontiersman All memberships include a membership card, free admission to the who understood the ways of tribal Native America. A true enigma, Museum, notice of upcoming events and The Carson Courier, the Carson remains to this day a revered yet misunderstood historical Museum’s semi-annual newsletter. figure. Yes! I want to be a member! I will pay by: _____check Modern biographers portray Carson as a complex and enigmatic man _____cash who participated in many of the major historical events of America’s _____credit card (please call the Museum to pay via cc) westward expansion.