1867 U.S. Topo Bureau Bosque Redondo Fort Stanton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kokoro Kara Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation

Fall 2016 KOKORO KARA HEART MOUNTAIN WYOMING FOUNDATION •”A Song of America:” 2016 Heart Mountain Pilgrimage •Exhibit Preview: Ansel Adams Meets Yoshio Okumoto The Walk Family: Generous Heart Mountain Champions All cover photographs from HMWF Okumoto Collection • Compassionate Witnesses: Chair Shirley Ann Higuchi “It was a miserably cold day and the documented the Heart Mountain journey, HMWF a Leadership in History Award people looked terribly cold. They got on and our longtime supporter Margot Walk, from the American Association for State the train and went away. My sister and I also provided tremendous emotional and Local History. He also brought in discovered we were crying. It wasn’t the support and compassion. more than $500,000 in grants to facilitate wind that was making us cry. It was such Executive Director Brian Liesinger, new programs, preserve buildings and a sad sight,” recalls 81-year-old LaDonna who came to us with lasting ties to Heart create special exhibitions. He has fostered Zall, one of our treasured board members Mountain, has also become one of those partnerships with the National Park who saw the last train of incarcerees leave individuals we esteem as a compassionate Service, the Japanese American National Heart Mountain in 1945. A pipeliner’s witness. When his World War II veteran Museum, the Wyoming Humanities daughter and our honorary Nisei, she grandparents acquired rights to collect Council and the Wyoming State Historic remembers the camp’s materials from the Preservation Office. Thank you, Brian, for eight-foot fence and camp, they crafted their all you have done to advance our mission guard towers and homestead from one of and your continued commitment to help continues to advocate the hospital buildings. -

Case Studies of the Early Reservation Years 1867-1901

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1983 Diversity of assimilation: Case studies of the early reservation years 1867-1901 Ira E. Lax The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lax, Ira E., "Diversity of assimilation: Case studies of the early reservation years 1867-1901" (1983). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5390. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5390 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR, Mansfield Library University of Montana Date : __JL 1 8 v «3> THE DIVERSITY OF ASSIMILATION CASE STUDIES OF THE EARLY RESERVATION YEARS, 1867 - 1901 by Ira E. Lax B.A., Oakland University, 1969 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1983 Ap>p|ov&d^ by : f) i (X_x.Aa^ Chairman, Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate Sdnool Date UMI Number: EP40854 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

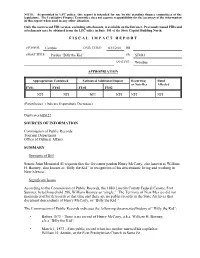

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

Kip Tokuda Civil Liberties Program

Kip Tokuda Civil Liberties Program 1. Purpose: The Kip Tokuda competitive grant program supports the intent of RCW 28A.300.405 to do one or both of the following: 1) educate the public regarding the history and lessons of the World War II exclusion, removal, and detention of persons of Japanese ancestry through the development, coordination, and distribution of new educational materials and the development of curriculum materials to complement and augment resources currently available on this subject matter; and 2) develop videos, plays, presentations, speaker bureaus, and exhibitions for presentation to elementary schools, secondary schools, community colleges, and other interested parties. 2. Description of services provided: Grants were provided to the following individuals and organizations: Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community (BIJAC): BIJAC offered workshops featuring four oral history documentary films of the Japanese American WWII experience and accompanying curricula aligning with OSPI-developed Assessments for use in distance-learning lessons during the COVID- 19 pandemic, and developed online interactive activities to use with the oral history films in online workshops. Erin Shigaki: In the first phase of the grant Erin used the funds to revise the design of three wall murals about the Japanese American exclusion and detention located in what was the historic Japantown or Nihonmachi in Seattle, WA. The first and second locations are in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District in “Nihonmachi Alley” and the third location is the side of the Densho building located on Jackson Street. Erin spent time working with a fabricator regarding material options and installation. Densho (JALP): From January to June, the content staff completed articles on a range of confinement sites administered by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA), the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), and the U.S. -

Overlooked No More: Ralph Lazo, Who Voluntarily Lived in an Internment Camp - the New York Times

11/24/2019 Overlooked No More: Ralph Lazo, Who Voluntarily Lived in an Internment Camp - The New York Times Overlooked No More: Ralph Lazo, Who Voluntarily Lived in an Internment Camp About 115,000 Japanese-Americans on the West Coast were incarcerated after Pearl Harbor, and Lazo, who was Mexican-American, joined them in a bold act of solidarity. July 3, 2019 Overlooked is a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The Times. By Veronica Majerol When Ralph Lazo saw his Japanese-American friends being forced from their homes and into internment camps during World War II, he did something unexpected: He went with them. In the spring of 1942, Lazo, a 17-year-old high school student in Los Angeles, boarded a train and headed to the Manzanar Relocation Center, one of 10 internment camps authorized to house Japanese-Americans under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s executive order in the wake of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor a few months earlier. The camps, tucked in barren regions of the United States, would incarcerate around 115,000 people living in the West from 1942 to 1946 — two-thirds of them United States citizens. Unlike the other inmates, Lazo did not have to be there. A Mexican-American, he was the only known person to pretend to be Japanese so he could be willingly interned. What compelled Lazo to give up his freedom for two and a half years — sleeping in tar-paper-covered barracks, using open latrines and showers and waiting on long lines for meals in mess halls, on grounds surrounded by barbed-wire fencing and watched by guards in towers? He wanted to be with his friends. -

History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 82 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2007 Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial Jennifer Nez Denetdale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. "Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial." New Mexico Historical Review 82, 3 (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol82/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival HISTORY, DINE/NAVAJO MEMORY, AND THE BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL Jennifer Nez Denetdale n 4 June 2005, hundreds ofDine and their allies gathered at Fort Sumner, ONew Mexico, to officially open the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Sitting under an arbor, visitors listened to dignitaries interpret the meaning of the Long Walk, explain the four years ofimprisonment at the Bosque Redondo, and discuss the Navajos' return to their homeland in1868. Earlier that morn ing, a small gathering ofDine offered their prayers to the Holy People. l In the past twenty years, historic sites have become popular tourist attrac tions, partially as a result ofpartnerships between state historic preservation departments and the National Park Service. With the twin goals ofeducat ing the public about the American past and promoting their respective states as attractive travel destinations, park officials and public historians have also included Native American sites. -

![79 Stat. ] Public Law 89-188-Sept. 16, 1965 793](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7711/79-stat-public-law-89-188-sept-16-1965-793-387711.webp)

79 Stat. ] Public Law 89-188-Sept. 16, 1965 793

79 STAT. ] PUBLIC LAW 89-188-SEPT. 16, 1965 793 Public Law 89-188 AIM APT September 16, 1Q65 ^^^^^^ [H. R. 10775] To authorize certain eoiistruotion at military installations, and for other purposes. Be it enacted hy the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled^ stmction^Aia°hori- zation Act, 1966. TITLE I SEC. 101. The Secretary of the Army may establish or develop ^""^y- military installations and facilities by acquiring, constructing, con verting, rehabilitating, or installing permanent or temporary public vv^orks, including site preparations, appurtenances, utilities and equip ment for the following projects: INSIDE THE UNITED STATES CONTINENTAL UNITED STATES, LESS ARMY MATERIEL COMMAND (First Army) Fort Devens, Massachusetts: Hospital facilities and troop housing, $11,008,000. Fort Dix, New Jersey: Maintenance facilities, medical facilities, and troop housing, $17,948,000. Federal Office Building, Brooklyn, New York: Administrative facilities, $636,000. _ United States Military Academy, West Point, New York: Hospital facilities, troop housing and community facilities, and utilities, $18,089,000. (Second Army) Fort Belvoir, Virginia: Training facilities, and hospital facilities, $2,296,000. East Coast Radio Transmitter Station, Woodbridge, Virginia: Utilities, $211,000. Fort Eustis, Virginia: Utilities, $158,000. Fort Knox, Kentucky: Training facilities, maintenance facilities, troop housing, and community facilities, $15,422,000. Fort Lee, Virginia: Community facilities, $700,000. Fort Meade, Maryland: Ground improvements, $550,000. Fort Monroe, Virginia: Administrative facilities, $4,950,000. Vint Hill Farms, Virginia: Maintenance facilities, troop housing and utilities, $1,029,000. (Third Army) Fort Benning, Georgia: Maintenance facilities, troop housing and utilities, $5,325,000. -

COMANCHE COUNTY Oklahoma

COMANCHE COUNTY Oklahoma COMMUNITY HEALTH ASSESSMENT Initial Release December 2016 . Revised September 2017 Contents Section One Community Contributors 1 Introduction 2 Mobilizing for Action Through Planning and Partnerships MAPP 3 Section Two Community Description and Demographics 4 Mortality and Leading Causes of Deaths 5 Social Determinants of Health 5 Education, and Income 6 Section Three MAPP Assessments: Community Health Status 7 Community Themes and Strengths 8 Forces of Change 9 Local Public Health System 11 Section Four Five Priority Elements Mental Health 12 Poverty 13 Obesity 14 Violence and Crime 15 Substance Abuse (Tobacco, Alcohol, Drugs) 16 Next Steps 17 Resources References Cited Works R1 Appendix A Comanche County Demographics, US Census Bureau A1 Appendix B Comanche County State of the County Report B1 Appendix C 2014 State of the State’s Health, page 66 C1 Appendix D County Health Ranking and Roadmaps D1 Appendix E Kids Count Report E1 Appendix F Comanche County Community Themes and Strengths Survey Results F1 Appendix G Comanche County Forces of Change Survey Results G1 Appendix H Comanche County Local Public Health System Results H1 Appendix I Comanche County Asset Mapping I1 CHA Updated September 2017 Contents Continued Resources Added – Revised September 2017 Appendix J 500 Cities Project J1 Appendix K Comanche County State of the County Health Report K1 Appendix L Lawton Consolidation Plan L1 Appendix M Lawton Consolidation Plan Aerial View M1 CHA Updated September 2017 Comanche County Community Health Assessment Section 1—page 1 Community Contributors A special thank you to all the Community Contributors who volunteer their time and energy. -

Military and Veterans' Affairs Committee

MILITARY AND VETERANS' AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 2012 INTERIM FINAL REPORT New Mexico Legislature Legislative Council Service 411 State Capitol Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 MILITARY AND VETERANS' AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 2012 INTERIM FINAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 2012 Interim Summary 2012 Work Plan and Meeting Schedule Agendas Minutes Endorsed Legislation 2012 INTERIM SUMMARY MILITARY AND VETERANS' AFFAIRS COMMITTEE 2012 INTERIM SUMMARY The Military and Veterans' Affairs Committee held five meetings in 2012. The committee focused on many areas affecting veterans and military personnel, including: (1) housing issues; (2) family and community support; (3) treatment options for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); and (4) opportunities at educational institutions around the state. Don Arnold, a United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) prior approval lender and veteran advocate, gave a presentation to the committee on the problems some veterans are having with losing their homes and the foreclosure process. The committee suggested that Mr. Arnold work with Secretary of Veterans' Services Timothy L. Hale to discuss the issues and develop possible solutions. Representatives from Cannon Air Force Base and from the National Guard spoke about the comprehensive community and family support services provided to military personnel. These programs include relocation and transition assistance, financial management, youth and community programs and help with behavioral health, suicide prevention and sexual assault issues. The committee heard several presentations on the topic of PTSD, including the services available from community-based outpatient clinics and the New Mexico VA health care system. The VA is striving to provide effective treatments that can be accessed by all veterans in the state, including through telehealth services. -

Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 49 Number 2 Article 2 4-1-1974 Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946 Jake W. Spidle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Spidle, Jake W.. "Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946." New Mexico Historical Review 49, 2 (2021). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol49/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 93 AXIS INVASION OF THE AMERICAN WEST: POWS IN NEW MEXICO, 1942-1946 JAKE W. SPIDLE ON A FLAT, virtually treeless stretch of New Mexico prame, fourteen miles southeast of the town of Roswell, the wind now kicks up dust devils where Rommel's Afrikakorps once marched. A little over a mile from the Orchard Park siding of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific railroad line, down a dusty, still unpaved road, the concrete foundations of the Roswell Prisoner of War Internment Camp are still visible. They are all that are left from what was "home" for thousands of German soldiers during the period 1942-1946. Near Lordsburg there are similar ruins of another camp which at various times during the years 1942-1945 held Japanese-American internees from the Pacific Coast and both Italian and German prisoners of war. -

Microfilm Publication M617, Returns from U.S

Publication Number: M-617 Publication Title: Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916 Date Published: 1968 RETURNS FROM U.S. MILITARY POSTS, 1800-1916 On the 1550 rolls of this microfilm publication, M617, are reproduced returns from U.S. military posts from the early 1800's to 1916, with a few returns extending through 1917. Most of the returns are part of Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office; the remainder is part of Record Group 393, Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, and Record Group 395, Records of United States Army Overseas Operations and Commands, 1898-1942. The commanding officer of every post, as well ad commanders of all other bodies of troops such as department, division, brigade, regiment, or detachment, was required by Army Regulations to submit a return (a type of personnel report) to The Adjutant General at specified intervals, usually monthly, on forms provided by that office. Several additions and modifications were made in the form over the years, but basically it was designed to show the units that were stationed at a particular post and their strength, the names and duties of the officers, the number of officers present and absent, a listing of official communications received, and a record of events. In the early 19th century the form used for the post return usually was the same as the one used for regimental or organizational returns. Printed forms were issued by the Adjutant General’s Office, but more commonly used were manuscript forms patterned after the printed forms.