The Bosque Redondo Memorial Long Deserved, Long Overdue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribal Higher Education Contacts.Pdf

New Mexico Tribes/Pueblos Mescalero Apache Contact Person: Kelton Starr Acoma Pueblo Address: PO Box 277, Mescalero, NM 88340 Phone: (575) 464-4500 Contact Person: Lloyd Tortalita Fax: (575) 464-4508 Address: PO Box 307, Acoma, NM 87034 Phone: (505) 552-5121 Fax: (505) 552-6812 Nambe Pueblo E-mail: [email protected] Contact Person: Claudene Romero Address: RR 1 Box 117BB, Santa Fe, NM 87506 Cochiti Pueblo Phone: (505) 455-2036 ext. 126 Fax: (505) 455-2038 Contact Person: Curtis Chavez Address: 255 Cochiti St., Cochiti Pueblo, NM 87072 Phone: (505) 465-3115 Navajo Nation Fax: (505) 465-1135 Address: ONNSFA-Crownpoint Agency E-mail: [email protected] PO Box 1080,Crownpoint, NM 87313 Toll Free: (866) 254-9913 Eight Northern Pueblos Council Fax Number: (505) 786-2178 Email: [email protected] Contact Person: Rob Corabi Website: http://www.onnsfa.org/Home.aspx Address: 19 Industrial Park Rd. #3, Santa Fe, NM 87506 (other ONNSFA agency addresses may be found on the Phone: (505) 747-1593 website) Fax: (505) 455-1805 Ohkay Owingeh Isleta Pueblo Contact Person: Patricia Archuleta Contact Person: Jennifer Padilla Address: PO Box 1269, Ohkay Owingeh, NM 87566 Address: PO Box 1270, Isleta,NM 87022 Phone: (505) 852-2154 Phone: (505) 869-9720 Fax: (505) 852-3030 Fax: (505) 869-7573 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.isletapueblo.com Picuris Pueblo Contact Person: Yesca Sullivan Jemez Pueblo Address: PO Box 127, Penasco, NM 87553 Contact Person: Odessa Waquiu Phone: (575) 587-2519 Address: PO Box 100, Jemez Pueblo, -

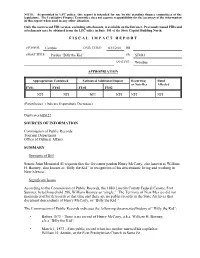

F I S C a L I M P a C T R E P O

NOTE: As provided in LFC policy, this report is intended for use by the standing finance committees of the legislature. The Legislative Finance Committee does not assume responsibility for the accuracy of the information in this report when used in any other situation. Only the most recent FIR version, excluding attachments, is available on the Intranet. Previously issued FIRs and attachments may be obtained from the LFC office in Suite 101 of the State Capitol Building North. F I S C A L I M P A C T R E P O R T SPONSOR: Campos DATE TYPED: 03/12/01 HB SHORT TITLE: Pardon “Billy the Kid” SB SJM43 ANALYST: Woodlee APPROPRIATION Appropriation Contained Estimated Additional Impact Recurring Fund or Non-Rec Affected FY01 FY02 FY01 FY02 NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI NFI (Parenthesis ( ) Indicate Expenditure Decreases) Duplicates HJM27 SOURCES OF INFORMATION Commission of Public Records Tourism Department Office of Cultural Affairs SUMMARY Synopsis of Bill Senate Joint Memorial 43 requests that the Governor pardon Henry McCarty, also known as William H. Bonney, also known as “Billy the Kid” in recognition of his descendants living and working in New Mexico. Significant Issues According to the Commission of Public Records, the 1880 Lincoln County Federal Census, Fort Sumner, listed household 286, William Bonney as “single.” The Territory of New Mexico did not maintain civil birth records at that time and there are no public records in the State Archives that document descendants of Henry McCarty, or “Billy the Kid.” The Commission of Public Records indicates the following documented history of “Billy the Kid”: • Before 1873 - There is no record of Henry McCarty, a.k.a. -

History, Dinã©/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 82 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2007 Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial Jennifer Nez Denetdale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. "Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival: History, Diné/Navajo Memory, and the Bosque Redondo Memorial." New Mexico Historical Review 82, 3 (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol82/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Discontinuities, Remembrances, and Cultural Survival HISTORY, DINE/NAVAJO MEMORY, AND THE BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL Jennifer Nez Denetdale n 4 June 2005, hundreds ofDine and their allies gathered at Fort Sumner, ONew Mexico, to officially open the Bosque Redondo Memorial. Sitting under an arbor, visitors listened to dignitaries interpret the meaning of the Long Walk, explain the four years ofimprisonment at the Bosque Redondo, and discuss the Navajos' return to their homeland in1868. Earlier that morn ing, a small gathering ofDine offered their prayers to the Holy People. l In the past twenty years, historic sites have become popular tourist attrac tions, partially as a result ofpartnerships between state historic preservation departments and the National Park Service. With the twin goals ofeducat ing the public about the American past and promoting their respective states as attractive travel destinations, park officials and public historians have also included Native American sites. -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

Journal of Arizona History Index, M

Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 NOTE: the index includes two citation formats. The format for Volumes 1-5 is: volume (issue): page number(s) The format for Volumes 6 -54 is: volume: page number(s) M McAdams, Cliff, book by, reviewed 26:242 McAdoo, Ellen W. 43:225 McAdoo, W. C. 18:194 McAdoo, William 36:52; 39:225; 43:225 McAhren, Ben 19:353 McAlister, M. J. 26:430 McAllester, David E., book coedited by, reviewed 20:144-46 McAllester, David P., book coedited by, reviewed 45:120 McAllister, James P. 49:4-6 McAllister, R. Burnell 43:51 McAllister, R. S. 43:47 McAllister, S. W. 8:171 n. 2 McAlpine, Tom 10:190 McAndrew, John “Boots”, photo of 36:288 McAnich, Fred, book reviewed by 49:74-75 books reviewed by 43:95-97 1 Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 McArtan, Neill, develops Pastime Park 31:20-22 death of 31:36-37 photo of 31:21 McArthur, Arthur 10:20 McArthur, Charles H. 21:171-72, 178; 33:277 photos 21:177, 180 McArthur, Douglas 38:278 McArthur, Lorraine (daughter), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Lorraine (mother), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Louise, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Perry 43:349 McArthur, Warren, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Warren, Jr. 33:276 article by and about 21:171-88 photos 21:174-75, 177, 180, 187 McAuley, (Mother Superior) Mary Catherine 39:264, 265, 285 McAuley, Skeet, book by, reviewed 31:438 McAuliffe, Helen W. -

Exemplary Programs in Indian Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 445 845 RC 022 569 AUTHOR Chavers, Dean, Ed. TITLE Exemplary Programs in Indian Education. Third Edition. INSTITUTION Native American Scholarship Fund, Inc., Albuquerque, NM. ISBN ISBN-1-929964-01-3 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 129p. AVAILABLE FROM Native American Scholarship Fund, Inc., 8200 Mountain Rd. NE, Suite 203, Albuquerque, NM 87110; Tel: 505-262-2351 ($39.95 plus $3.50 shipping). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132)-- Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Academic Achievement; Adult Education; *American Indian Education; American Indians; *Demonstration Programs; *Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; Evaluation Criteria; Higher Education; Program Descriptions ABSTRACT This book presents 16 exemplary programs in schools that enroll American Indian or Alaska Native students. Exemplary, by definition, means the top 5 percent of education programs in student outcomes. In most cases, these programs are in the top 1 percent. Each program entryincludes contact information, a narrative description, and in some cases, awards received, documentation of student outcomes, and other relevant information. Schools range from elementary through college and include public, private, tribal, and nonprofit. Programs address student support services, comprehensive school improvement, dropout prevention, adult education, college preparation, technology integration, and other areas. All 16 programs are summarized on one page in the beginning of the book, and program characteristics are presented in chart form. A brief history of Indian education is followed by a description of the 11 elements that are characteristic of exemplary programs: acknowledgement of the problem; set priorities for problems; vision, planning; commitment; restructuring and retraining; goal setting; experimentation, testing, and evaluation; outreach; expertise; and administrative support. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Navajo Nation to Obtain an Original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 Document

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 22, 2019 Navajo Nation to obtain an original Naaltsoos Sání – Treaty of 1868 document WINDOW ROCK – Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer are pleased to announce the generous donation of one of three original Navajo Treaty of 1868, also known as Naaltsoos Sání, documents to the Navajo Nation. On June 1, 1868, three copies of the Treaty of 1868 were issued at Fort Sumner, N.M. One copy was presented to the U.S. Government, which is housed in the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington D.C. The second copy was given to Navajo leader Barboncito – its current whereabouts are unknown. The third unsigned copy was presented to the Indian Peace Commissioner, Samuel F. Tappan. The original document is also known as the “Tappan Copy” is being donated to the Navajo Nation by Clare “Kitty” P. Weaver, the niece of Samuel F. Tappan, who was the Indian Peace Commissioner at the time of the signing of the treaty in 1868. “On behalf of the Navajo Nation, it is an honor to accept the donation from Mrs. Weaver and her family. The Naaltsoos Sání holds significant cultural and symbolic value to the Navajo people. It marks the return of our people from Bosque Redondo to our sacred homelands and the beginning of a prosperous future built on the strength and resilience of our people,” said President Nez. Following the signing of the Treaty of 1868, our Diné people rebuilt their homes, revitalized their livestock and crops that were destroyed at the hands of the federal government, he added. -

Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Draft Long Walk National Historic Trail Feasibility Study / Environmental Impact Statement Arizona • New Mexico DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Thanks to the New Mexico Humanities Council and the Western National Parks and Monuments Association for their important contributions to this study. DRAFT LONG WALK NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAIL FEASIBILITY STUDY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Apache, Coconino, Navajo Counties, Arizona; Bernalillo, Cibola, De Baca, Guadalupe, Lincoln, McKinley, Mora, Otero, Santa Fe, Sandoval, Torrance, Valencia Counties, New Mexico The purpose of this study is to evaluate the suitability and feasibility of designating the routes known as the “Long Walk” of the Mescalero Apache and the Navajo people (1862-1868) as a national historic trail under the study provisions of the National Trails System Act (Public Law 90-543). This study provides necessary information for evaluating the national significance of the Long Walk, which refers to the U.S. Army’s removal of the Mescalero Apache and Navajo people from their homelands to the Bosque Redondo Reservation in eastern New Mexico, and for potential designation of a national historic trail. Detailed administrative recommendations would be developed through the subsequent preparation of a comprehensive management plan if a national historic trail is designated. The three criteria for national historic trails, as defined in the National Trails System Act, have been applied and have been met for the proposed Long Walk National Historic Trail. The trail routes possess a high degree of integrity and significant potential for historical interest based on historic interpretation and appreciation. -

Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 10-2-1909 Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909 Review Pub. Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news Recommended Citation Review Pub. Co.. "Fort Sumner Review, 10-02-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ft_sumner_review_news/9 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fort Sumner Review, 1909-1911 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. lie rort Sumner Review VOL 2--- 12. FORT SUMNER, (Sunnyside Post office), GUADALUPE COUNTY, N. M., OCTOBER 2, 1909. $1 A YEAR, CASH. JL Murder of Miss Hattonl. Thc !oenf of the ,imeis with-- ! The Small Holding . in a mue or aanta Kosa, among ; LOCALETTES i I at Santa Rosa. ' the hilla overlooking the city, Claims. and while wild, yet the roitd (Special Correspondence. ) within a short distance is much AU persons who are .claiming Rosa, N M, Sept. 27- .- land because they have lived on Our Invitation George B. Deen, wife, and Santa traveled. Miss 18, the same for years little son, were called to Portales Sarah Hatton, daughter Miss Hatton was a beautiful twent' or Mrs. R. I. young i more, these claims 'being com- - Tuesday to attend the funeral of Mr. and Hatton of lady, a leader among the of a little nephew. Los Tanos, a small station on the young folks of her town and had monly kno.wn as "small holding Rack Island, nine miles east of many friends here. -

Alamo Navajo Community School “Home of the Cougars” Alamo Navajo School Board Basketball Schedule President: 2019-2020 Raymond Apachito Sr

Alamo Navajo Community School “Home of the Cougars” Alamo Navajo School Board Basketball Schedule President: 2019-2020 Raymond Apachito Sr. 11/22 Quemado Tournament TBA JH Vice-President: 12/03 Tohajiilee-HOME 4 pm JH 12/5-12/7 Steer Stampede Tournament V John Apachito Jr Magdalena TBA V Members: 12/5-12/7 Rehoboth Boys JV Tournament Steve Guerro Gallup TBA JHB 12/10 Mountainair-AWAY 4 pm JVB, V Charlotte Guerro 12/12-12/14 Mescalero Holiday Classic Mescalero TBA V Fighting for Native Rights 12/17 Mountainair-HOME 4 pm JVB, V 12/19 Reserve-HOME 3 pm JVB, V By: Kenyon Apachito 12/20 Evangel Christian-AWAY 3:30 pm V November is the month that hosts National Native 12/26-12/27 Striking Eagle Tournament American Heritage Month. What better way to celebrate the month than remember our Native Albuquerque TBA V American icons? Most people could easily 01/03 Magdalena JH & JV Tournament TBA recognize Geronimo, Sitting Bull, Manuelito, Crazy 01/04 Quemado -AWAY 11 am JH, JV, V Horse, and also Sacagawea. They each hold their 01/06 Magdalena -HOME 4 pm JH purposes of unique ventures, but do you know 01/09 Reserve-HOME 4 pm JH, JVB about the Native American who emerged from the 01/10 Quemado -HOME 11 am JH, JV, V Oglala Lakota tribe? Born in 1868, he was one of 01/14 Jemez-HOME 5 pm V the many Native American icons to fight for Native 01/16 Tohajiilee-AWAY 4 pm JH rights. 01/16 Walatowa -AWAY 4 pm V His white name was “Luther Standing Bear” and his family name was Óta Kté, which meant 01/18 Pine Hill-AWAY 1 pm JV, V “Plenty Kill”.