Cheísevaríerlí^

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Complete Book of Cheese by Robert Carlton Brown

THE COMPLETE BOOK OF CHEESE BY ROBERT CARLTON BROWN Chapter One I Remember Cheese Cheese market day in a town in the north of Holland. All the cheese- fanciers are out, thumping the cannon-ball Edams and the millstone Goudas with their bare red knuckles, plugging in with a hollow steel tool for samples. In Holland the business of judging a crumb of cheese has been taken with great seriousness for centuries. The abracadabra is comparable to that of the wine-taster or tea-taster. These Edamers have the trained ear of music-masters and, merely by knuckle-rapping, can tell down to an air pocket left by a gas bubble just how mature the interior is. The connoisseurs use gingerbread as a mouth-freshener; and I, too, that sunny day among the Edams, kept my gingerbread handy and made my way from one fine cheese to another, trying out generous plugs from the heaped cannon balls that looked like the ammunition dump at Antietam. I remember another market day, this time in Lucerne. All morning I stocked up on good Schweizerkäse and better Gruyère. For lunch I had cheese salad. All around me the farmers were rolling two- hundred-pound Emmentalers, bigger than oxcart wheels. I sat in a little café, absorbing cheese and cheese lore in equal quantities. I learned that a prize cheese must be chock-full of equal-sized eyes, the gas holes produced during fermentation. They must glisten like polished bar glass. The cheese itself must be of a light, lemonish yellow. Its flavor must be nutlike. -

Specialty Cheese Some Items May Require Pre-Order Contact Your Sales Representative for More Information California Blue Item Origin / Milk Description

Specialty Cheese Some items may require pre-order Contact your sales representative for more information California Blue Item Origin / Milk Description Point Reyes Marshall, CA Made with milk from cows that graze on the Original Blue Raw certified organic, green pastured hills overlooking 9172 ~6 LB Wheel Cow Milk Tomales Bay, this blue is made with hours of 11565 5 LB Crumbles milking and then ages for a minimum of six Pre-order: months resulting in a creamier style. Point Reyes Marshall, CA Inspired by the sheer natural beauty and cool Bay Blue Pasteurized coastal climate of Point Reyes, Bay Blue is a 17293 ~5 LB Wheel Cow Milk rustic-style blue cheese, with a beautiful natural Pre-order: rind, fudgy texture, and a sweet, salted caramel finish. Shaft's CA / WI A savory, full flavored blue cheese aged for a Blue Cheese Pasteurized minimum of one year. Made in Wisconsin by a 8267 ~6 LB Wheel Cow Milk Master Cheesemaker, this cheese is aged in Pre-order: HYW California - in an abandoned gold mine converted into the perfect aging facility. Shaft's CA / WI A classic, elegant bleu vein cheese aged for a Ellie's Blue Cheese Pasteurized minimum of 24 months. The additional aging 12492 ~3 LB Wheel Cow Milk process creates a rare and unique cheese that Pre-order: HYW has a smooth, creamy taste with a sweet finish. Cheddar Item Origin / Milk Description Fiscalini Cheese Co Modesto, CA Fiscalini's Bandage Wrapped Cheddar is made Bandage Wrapped Pasteurized using traditional methods and aged for at least 16 Cheddar Cow Milk months. -

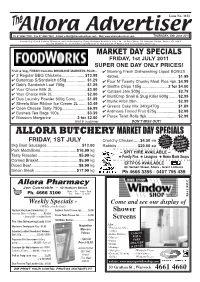

Allora Advertiser Ph 07 4666 3128 - Fax 07 4666 3822 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web THURSDAY, 30Th June 2011

Issue No. 3152 The Allora Advertiser Ph 07 4666 3128 - Fax 07 4666 3822 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web www.alloraadvertiser.com THURSDAY, 30th June 2011 Printed by David Patrick Gleeson and Published by Dairy Brokers Australia Pty. Ltd., at the Office, 53 Herbert Street, Allora, Q. 4362 Issued Weekly as an Advertising Medium to the people of Allora and surrounding Districts. MARKET DAY SPECIALS FRIDAY, 1st JULY 2011 SUPER ONE DAY ONLY PRICES! Fruit & Veg, FRESH from the BRISBANE MARKETS PLUS… ✔ Morning Fresh Dishwashing Liquid BONUS ✔ 2 Regular BBQ Chickens .................... $13.98 450mL .................................................... $1.99 ✔ Buttercup S/Sandwich 650g .................. $1.29 ✔ Four N' Twenty Chunky Meat Pies 4pk . $4.99 ✔ Deb's Sandwich Loaf 700g ................... $1.29 ✔ Smiths Chips 185g ....................... 2 for $4.00 ✔ Your Choice Milk 3L .............................. $3.00 ✔ Cottees Jam 500g ................................. $2.79 ✔ Your Choice Milk 2L .............................. $2.00 ✔ MultiCrop Snail & Slug Killer 600g ........ $2.99 ✔ Duo Laundry Powder 500g Conc. ........ $1.89 ✔ Multix Alfoil 20m .................................... $2.99 ✔ Streets Blue Ribbon Ice Cream 2L ....... $3.49 ✔ Greens Cake Mix 340g/470g ................ $1.89 ✔ Coon Cheese Tasty 750g ...................... $6.99 ✔ ✔ Bushels Tea Bags 100s ......................... $3.39 Ardmona Tinned Fruit 825g ................... $2.99 ✔ Blossom Margarine ...................... 2 for $2.00 ✔ Purex Toilet Rolls 9pk -

2020 World Championship Cheese Contest

2020 World Championship Cheese Contest Winners, Scores, Highlights March 3-5, 2020 | Madison, Wisconsin ® presented by the Cheese Reporter and the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association World Cheese Contest ® Champions 2020 1998 1976 MICHAEL SPYCHER & PER OLESEN RYKELE SYTSEMA GOURMINO AG Denmark Netherlands Switzerland 1996 1974 2018 HANS DEKKERS GLEN WARD MICHEL TOUYAROU & Netherlands Wisconsin, USA SAVENCIA CHEESE USA France 1994 1972 JENS JENSEN DOMENICO ROCCA 2016 Denmark Italy TEAM EMMI ROTH USA Fitchburg, Wisconsin USA 1992 1970 OLE BRANDER LARRY HARMS 2014 Denmark Iowa, USA GERARD SINNESBERGER Gams, Switzerland 1990 1968 JOSEF SCHROLL HARVEY SCHNEIDER 2012 Austria Wisconsin, USA TEAM STEENDEREN Wolvega, Netherlands 1988 1966 DALE OLSON LOUIS BIDDLE 2010 Wisconsin, USA Wisconsin, USA CEDRIC VUILLE Switzerland 1986 1964 REJEAN GALIPEAU IRVING CUTT 2008 Ontario, Canada Ontario, Canada MICHAEL SPYCHER Switzerland 1984 1962 ROLAND TESS VINCENT THOMPSON 2006 Wisconsin, USA Wisconsin, USA CHRISTIAN WUTHRICH Switzerland 1982 1960 JULIE HOOK CARL HUBER 2004 Wisconsin, USA Wisconsin, USA MEINT SCHEENSTRA Netherlands 1980 1958 LEIF OLESEN RONALD E. JOHNSON 2002 Denmark Wisconsin, USA CRAIG SCENEY Australia 1978 1957 FRANZ HABERLANDER JOHN C. REDISKE 2000 Austria Wisconsin, USA KEVIN WALSH Tasmania, Australia Discovering the Winning World’s Best Dairy Results Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association was honored to host an international team of judges and an impressive array of samples of 2020 cheese, butter, yogurt and dairy ingredients from around the globe at the 2020 World Championship Cheese Contest March 3-5 in Madison. World Champion It was our largest event ever, with a breath-taking 3,667 entries from Michael Spycher, Mountain 26 nations and 36 American states. -

Innovation and Marketing Strategies for PDO Products: the Case of “Parmigiano Reggiano” As an Ingredient

Innovation and marketing strategies for PDO products: the case of “Parmigiano Reggiano” as an ingredient Maria Cecilia Mancini – Claudio Consiglieri Department of Economics - Parma University The aim } The aim is to examine one type of innovation, the use of placed-based products as ingredients and a strategy to re-launch those products having a mature market. } The research aims to focus on possible consequences on the market and identify medium - long term critical aspects. Outline } The context of the research } The theoretical framework: product life cycle and information asymmetry } The case study: the PDO Parmigiano Reggiano cheese as ingredient in processed cheese (triangles and slices) } Final remarks The context of the research } Typical products and sustainable development of rural areas } Typical products and their positioning in the framework of the new patterns of food consumption } Consumer needs change depending on consumption contexts } What are efficient marketing strategies for typical products? } There’s no a single strategy. The theoretical framework: the product life cycle Life cycle of an agri-food product Source: Kotler and Scott, 1998 The theoretical framework: the information asymmetry } Information asymmetry exists on a market where not all agents have the necessary information available to make an optimum allocation of resources (Akerlof, 1970; Klein and Leffler, 1981, Shapiro, 1983, Stiglitz 1987) and this leads to lack of information which works to consumers’ disadvantage when they are not able to verify credence attributes (Darby and Kami, 1973; Anania and Nisticò, 2004). Relationship between information asimmetry and “PDO product as ingredient” strategy PDO PRODUCT AS INGREDIENT Credence attributes asimmetry PROCESSED FOOD PRODUCTS Communication of credence attributes Information MARKET A case study from the dairy sector: PDO Parmigiano Reggiano cheese In Italy, Parmigiano Reggiano cheese is an example of a PDO product in the commercial stage of maturity. -

Studies on a Newly Developed White Cheese. Edward Halim Youssef Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 Studies on a Newly Developed White Cheese. Edward Halim Youssef Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Youssef, Edward Halim, "Studies on a Newly Developed White Cheese." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2101. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2101 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-3537 YOUSSEF, Edward Halim, 1939- STUDIES ON A NEWLY DEVELOPED WHITE CHEESE. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1971 Agriculture, general I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan @ 1971 EDWARD HALIM YOUSSEF ALL RIGHTS RESERVED THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED STUDIES ON A NEWLY DEVELOPED WHITE CHEESE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Hie Department of Dairy Science by Edward Halim Youssef B.S., Ain Shames University, Cairo, Egypt, 1959 M.S., Ain Shames University, Cairo, Egypt, 1966 August, 1971 t / PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have in d is tin c t prin t. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to his major Professor, Dr. J. -

Flavor Description and Classification of Selected Natural Cheeses Delores H

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by K-State Research Exchange Culinary Arts and Sciences V: Global and National Perspectives, 2005, ed. Edwards, J.S.A., Kowrygo, B, & Rejman, K. pp 641-654, Publisher, Worshipful Company of Cooks Research Centre, Bournemouth, Poole, UK Flavor description and classification of selected natural cheeses Delores H. Chambers1, Edgar Chambers IV1 and Dallas Johnson2 1The Sensory Analysis Center, Department of Human Nutrition, Kansas State University, Justin Hall, Manhattan, KS 66506-1407, USA 2Department of Statistics, Kansas State University, Dickens Hall, Manhattan, KS 66506, USA Abstract Intensities of 30 flavor attributes were measured for 42 cheeses. Rated intensities of flavor characteristics generally fell in the low to moderate range for all cheeses. Some of the flavor characteristics (dairy fat, dairy sour, dairy sweet, sharp, astringent, bitter, salty, sour, and sweet) were present in all cheeses, and some (cooked milk, animalic, goaty, fruity, moldy, mushroom, and nutty) were specific to only a few of the cheeses evaluated in this study. The flavor of each of the 42 cheeses is described. Similarities in flavor were observed among many of the individual cheeses. Therefore, a clustering scheme was developed to show the overall flavor relationships among the cheeses. Those relationships are schematically represented by a tree diagram. Proximity on the tree diagram indicates a high degree of flavor similarity among the types of cheese. Introduction In most countries, consumption of cheese has been on the rise over the past decades (Richards, 1989; Magretti, 1996; Havrila, 1997; Hoebermann, 1997; Anonymous, 2002). -

Servizio Informativo N° 28/2020 Del 10 Luglio 2020 - RISERVATO AGLI ASSOCIATI

A S S O C A S E A R I ASSOCIAZIONE COMMERCIO PRODOTTI LATTIERO - CASEARI Servizio informativo N° 28/2020 del 10 Luglio 2020 - RISERVATO AGLI ASSOCIATI - NORME E NOTIZIE MERCATO LATTIERO-CASEARIO - Andamento settimanale PAG. 02 BIOLOGICO - Etichettatura, le modifiche al regolamento: www.alimentando.info PAG. 03 SCAMBI UE/MERCOSUR - Accordo, aggiornamenti sui prossimi step PAG. 03 ESPORTAZIONI VERSO PAESI TERZI - BRASILE - Preoccupazioni commerciali della Commissione UE PAG. 03 STATI UNITI E FRANCIA - I formaggi tradizionali reagiscono al Covid-19: Clal PAG. 04 STATI UNITI - Esteso il "Farmers to Families Food Box Program" PAG. 05 OCEANIA - Situazione dal 22 giugno al 3 luglio 2020: Clal PAG. 05 FORMAGGI D.O.P. E I.G.P. - Nuovi testi normativi PAG. 06 FORMAGGI D.O.P. - "PARMIGIANO REGGIANO" - In vendita a Natale lo stagionato 40 mesi PAG. 07 FORMAGGI D.O.P. - "PARMIGIANO REGGIANO" - Dal produttore al consumatore, nasce il nuovo shop on- line: www.parmigianoreggiano.it PAG. 07 FORMAGGI - Nasce il presidio Slow Food del pecorino di Carmasciano: www.alimentando.info PAG. 08 FORMAGGI D.O.P. - "PECORINO ROMANO" - Avviato un progetto promozionale in Giappone PAG. 08 FORMAGGI D.O.P. - "ASIAGO" - Futuro sempre più naturale e salutare: www.asiagocheese.it PAG. 08 FIERE ED EVENTI – CremonaFiere conferma tutte le manifestazioni in autunno: www.alimentando.info PAG. 09 MERCATO AGROALIMENTARE E LATTIERO-CASEARIO - Le news di Formaggi&Consumi dal 4 al 10 luglio 2020 PAG. 10 MERCATO LATTIERO-CASEARIO - Asta Global Dairy Trade del 07/07/20: Clal PAG. 13 FORMAGGI D.O.P. - "GORGONZOLA" - Produzione giugno 2020: Consorzio di Tutela del Formaggio Gorgonzola PAG. -

Business Class

BUSINESS CLASS MENÙ DEL PIEMONTE Piemonte Cucina raffinata, cibi freschi e sapori antichi della Regione BEST AIRLINE CUISINE Per la settima volta consecutiva Alitalia vince il Best Airline Cuisine, che premia la qualità gastronomica dei menù serviti a bordo ITALIANO Volare ha il sapore della cucina italiana La cucina italiana è conosciuta e apprezzata in tutto il mondo: ogni piatto raccoglie in sé la storia, la cultura e la tradizione del nostro Paese e delle sue Regioni. Alitalia è orgogliosa di offrirle i suoi esclusivi menù regionali, dandole l’opportunità di assaporare il vero “Made of Italy” su ogni volo. Oggi vi accompagniamo alla scoperta dei profumi e dei sapori del Piemonte. La cucina piemontese è tra le più raffinate e varie d’Italia, avendo unito le vecchie tradizioni contadine all’influenza gastronomica della vicina Francia. I particolari distintivi di questa cucina sono: l’utilizzo di verdure crude, i saporiti formaggi, la presenza estesa dei tartufi e l’uso attento dell’aglio che ha dato origine alla tradizionale bagna cauda. Un elemento importante nella cucina tipica della regione è il riso, che ha in questa zona la maggior produzione a livello europeo. I prodotti tipici della regione soddisfano i gusti e le esigenze dei Piemontesi: dall’aperitivo con i famosi grissini torinesi, alla farinata e il fritto misto, fino ai dolci di fantasiosa pasticceria come gli amaretti, il torrone alla nocciola e il gianduia. Durante il nostro viaggio, vi faremo sperimentare il meglio del Piemonte in ricette reinterpretate in chiave moderna -

Cheeses of Italy Hard 2396.Pdf

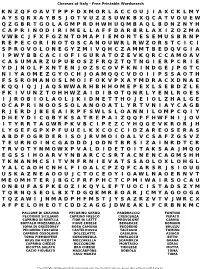

Cheeses of Italy - Free Printable Wordsearch KNZQFOAVTPPFDXMORLACC OUJIAXCKLMY AYSQRXAYBSJOTVUZZSUW KBXQCATVOUEW QZGBRTGOLAGMPRDHWHUQMBA QLBDNZNYH CAPRINODIRIMELLAFF DARBRLAXIZOZMA VWBCJFXFGZNTOMAPIEMO NTESEMUSBRNP REPECORINOTOSCANOUWRL RWZORSTCICI SPROVOLONEGYZMIVQHCZA MMTBEDQVGIA IPWYBBCACIOFIGURATO ZEVKQRCCAMOAV CASUMARZUPUBOSZFRQZTQ TNGIERPCRIE YDJNOLFXNTENJOZSCOV FKNINDGEJPGTC NIYAOMEZGYOCHJOAMQQCV DOIIPSSAOTH FSSROMANOSLMOIFOKVPXA YMDRACXDNAE KQQIQJJAQSWWARHBHHOME PEXLSEBDZLE FKIVUNZTOHHWZAIDIBO TQNRLYENLROES IJROBIOLAOLJKIDNE TTHOJEIOLZHALGE OCAPRINOOSSOLANOOATL YRTVNIAYCAGB RJERDJBEEAIRPFSWLS LOANNILOMPCQIY DHEYDICGBYKSATREPAI ZQQFFHWFNIJOV ITYRRTAGWRPKVBCIPEZ CYHQGEVKRORJH LYGEFGPXPFUUELKXCOCC IDZAREOSERAS ABDFOGRDERISOJRVMOI OALVCSAFZGSVZ TEURNOINCGADDDJODNTB RSIZAINRDTCR TRVOTYNMOWXPVALDIDETO ITAKSAAJMQO EGSSIHOARVYNBARCCSRT ACNENCAGMSHH TKNANMCSITVNFRNIEVA TSSAOLOXLOHGL YALCAOHCNHLFIOALCPZ QFCARSRJSIOUG USKAZNEAOOUJCTOCEOYI GAWLNAOERNVT MEOMHTERJBGCFRFPHCTC PMIWAIRSOCAU ONBUFASPKEOZIKQYLEF TUOCISTADSZYM TQRNQSEOLBXTDGQKMREOAR JCMYAGOOGA TQZAWIJNMADPHFMSTJYS AZRZVTVJWRCX AFPELOHEOTCDDZAGGJDW EAKLFCRBNKMC PALLONE DI GRAVINA PECORINO SARDO PADDRACCIO FONTINA PECORINO SICILIANO CAPRINO FRESCO CRESCENZA PEPATO CAPRINO DI RIMELLA FIOR DI LATTE PROVOLONE CARNIA BUFFALO MOZZARELLA PIAVE CHEESE BERGKASE ROMANO TOMA DI GRESSONEY ROSA CAMUNA PECORINO BRUZZU PECORINO TOSCANO CASTELROSSO TALEGGIO TOMINO CAPRINO OSSOLANO DOLCELATTE CASALINA ASIAGO TOMA PIEMONTESE GORGONZOLA MORLACCO BITTO BRUS DA RICOTTA MOZZARELLA SCAMORZA GRANA CAPRINO -

B-168835 Use of Monterey Cheese Imported from New Zealand

B-1168835 Dear Senator Nelson: Reference is made to your letter dated April 16, 1970, in which you requested that we invest‘igate whether Monterey cheese imported from New Zealand under the quota category of "Other cheese" is being used in place of cheddar cheese in the manufacture of American-type processed cheese or cheese foods. You stated that the standards of identrty of the Food__-- and - Drug- -,,..._Administration do not authorize the use of Monterey cheese for manufacturing processed American cheese or processed American cheese foods. You suggested that we make a spot check of-a limited number of shipments imported from New Zealand to determine whether Government reg- ulations are being violated. D Part.19 of title 21, Code-of Federal Regulations (CFR), sets forth definitions and standard-s under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (21 U.S.C. 301) for cheese and cheese products. Sections 19.750(a)(6) and 19.750(e)<2)(ii.I which pertain to pasteurized process cheese state: "The weight of each variety of cheese in a pasteurized process cheese made from two varieties of cheese is not less than 25 percent of the total weight of bothg* * *. These limits do not apply to the quantity of cheddar cheeses washed curd cheese, Colby cheese and granular cheese in mixtures which are designated as 'American cheese9 as prescribed in paragraph (e)(2)(ii) of this section. Such mixtures are considered as one variety of cheese for the purposes of this subparagraph." "II-I case it is made of cheddar cheese, washed curd cheese, colby cheese, or -

Bovine Benefactories: an Examination of the Role of Religion in Cow Sanctuaries Across the United States

BOVINE BENEFACTORIES: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN COW SANCTUARIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES _______________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________ by Thomas Hellmuth Berendt August, 2018 Examing Committee Members: Sydney White, Advisory Chair, TU Department of Religion Terry Rey, TU Department of Religion Laura Levitt, TU Department of Religion Tom Waidzunas, External Member, TU Deparment of Sociology ABSTRACT This study examines the growing phenomenon to protect the bovine in the United States and will question to what extent religion plays a role in the formation of bovine sanctuaries. My research has unearthed that there are approximately 454 animal sanctuaries in the United States, of which 146 are dedicated to farm animals. However, of this 166 only 4 are dedicated to pigs, while 17 are specifically dedicated to the bovine. Furthermore, another 50, though not specifically dedicated to cows, do use the cow as the main symbol for their logo. Therefore the bovine is seemingly more represented and protected than any other farm animal in sanctuaries across the United States. The question is why the bovine, and how much has religion played a role in elevating this particular animal above all others. Furthermore, what constitutes a sanctuary? Does