Sugar Ray's Bitterness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impartiality in Opinion Content (July 2008)

Quality Assurance Project 5: Impartiality (Opinion Content) Final Report July 2008 Advise. Verify. Review ABC Editorial Policies Editorial Policies The Editorial Policies of the ABC are its leading standards and a day-to-day reference for makers of ABC content. The Editorial Policies – • give practical shape to statutory obligations in the ABC Act; • set out the ABC’s self-regulatory standards and how to enforce them; and • describe and explain to staff and the community the editorial and ethical principles fundamental to the ABC. The role of Director Editorial Policies was established in 2007 and comprises three main functions: to advise, verify and review. The verification function principally involves the design and implementation of quality assurance projects to allow the ABC to assess whether it is meeting the standards required of it and to contribute to continuous improvement of the national public broadcaster and its content. Acknowledgements The project gained from the sustained efforts of several people, and the Director Editorial Policies acknowledges: Denis Muller, Michelle Fisher, Manager Research, and Jessica List, Executive Assistant. Thanks also to Ian Carroll and John Cameron, respectively the Directors of the Innovation Division and the News Division, and to their senior staff, whose engagement over the details of editorial decision-making gave the project layers that an assessment of this sort usually lacks. This paper is published by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation © 2008 ABC For information about the paper, please contact: Director Editorial Policies ABC Southbank Centre GPO Box 9994 Melbourne VIC 3001 Phone: +61 3 9626 1631 Email: [email protected] QA Project 05 – Final Report July 2008 ABC Editorial Policies Foreword Opinion and impartiality – are there any other words which, when paired, are more fraught for a public broadcaster? Is any other pair of words more apparently paradoxical? Opinion content is commissioned or acquired by the ABC to provide a particular perspective or point of view. -

The Complete Book of Cheese by Robert Carlton Brown

THE COMPLETE BOOK OF CHEESE BY ROBERT CARLTON BROWN Chapter One I Remember Cheese Cheese market day in a town in the north of Holland. All the cheese- fanciers are out, thumping the cannon-ball Edams and the millstone Goudas with their bare red knuckles, plugging in with a hollow steel tool for samples. In Holland the business of judging a crumb of cheese has been taken with great seriousness for centuries. The abracadabra is comparable to that of the wine-taster or tea-taster. These Edamers have the trained ear of music-masters and, merely by knuckle-rapping, can tell down to an air pocket left by a gas bubble just how mature the interior is. The connoisseurs use gingerbread as a mouth-freshener; and I, too, that sunny day among the Edams, kept my gingerbread handy and made my way from one fine cheese to another, trying out generous plugs from the heaped cannon balls that looked like the ammunition dump at Antietam. I remember another market day, this time in Lucerne. All morning I stocked up on good Schweizerkäse and better Gruyère. For lunch I had cheese salad. All around me the farmers were rolling two- hundred-pound Emmentalers, bigger than oxcart wheels. I sat in a little café, absorbing cheese and cheese lore in equal quantities. I learned that a prize cheese must be chock-full of equal-sized eyes, the gas holes produced during fermentation. They must glisten like polished bar glass. The cheese itself must be of a light, lemonish yellow. Its flavor must be nutlike. -

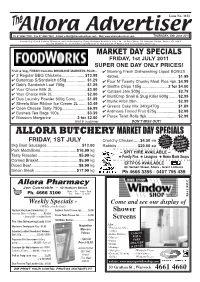

Allora Advertiser Ph 07 4666 3128 - Fax 07 4666 3822 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web THURSDAY, 30Th June 2011

Issue No. 3152 The Allora Advertiser Ph 07 4666 3128 - Fax 07 4666 3822 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web www.alloraadvertiser.com THURSDAY, 30th June 2011 Printed by David Patrick Gleeson and Published by Dairy Brokers Australia Pty. Ltd., at the Office, 53 Herbert Street, Allora, Q. 4362 Issued Weekly as an Advertising Medium to the people of Allora and surrounding Districts. MARKET DAY SPECIALS FRIDAY, 1st JULY 2011 SUPER ONE DAY ONLY PRICES! Fruit & Veg, FRESH from the BRISBANE MARKETS PLUS… ✔ Morning Fresh Dishwashing Liquid BONUS ✔ 2 Regular BBQ Chickens .................... $13.98 450mL .................................................... $1.99 ✔ Buttercup S/Sandwich 650g .................. $1.29 ✔ Four N' Twenty Chunky Meat Pies 4pk . $4.99 ✔ Deb's Sandwich Loaf 700g ................... $1.29 ✔ Smiths Chips 185g ....................... 2 for $4.00 ✔ Your Choice Milk 3L .............................. $3.00 ✔ Cottees Jam 500g ................................. $2.79 ✔ Your Choice Milk 2L .............................. $2.00 ✔ MultiCrop Snail & Slug Killer 600g ........ $2.99 ✔ Duo Laundry Powder 500g Conc. ........ $1.89 ✔ Multix Alfoil 20m .................................... $2.99 ✔ Streets Blue Ribbon Ice Cream 2L ....... $3.49 ✔ Greens Cake Mix 340g/470g ................ $1.89 ✔ Coon Cheese Tasty 750g ...................... $6.99 ✔ ✔ Bushels Tea Bags 100s ......................... $3.39 Ardmona Tinned Fruit 825g ................... $2.99 ✔ Blossom Margarine ...................... 2 for $2.00 ✔ Purex Toilet Rolls 9pk -

Mcondon.Apology.Feb0

The Hardest Word Author: Matthew Condon QWeekend Magazine (Brisbane, Australia) - Courier Mail Saturday, February 7, 2009 Was Kevin Rudd's "sorry" speech an act of heartfelt reconciliation or an empty gesture? One year on, Qweekend asks 14 indigenous Australians. To read it now, one year on, it no longer contains the fire glow of its initial delivery, nor does it make its way so directly to the human heart, removed from its astonishing emotional context on that morning of February 13 last year. But Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's now famous "sorry" speech to Australia's Stolen Generations, his first major act of parliamentary business as leader of the nation, remains a significant specimen of political rhetoric. Flat on the page it continues to show life because we can still readily connect it to the memory of that cloudy Canberra day, and how the nation stopped in the manner of great sporting events or great tragedy. More than 1.3 million Australians watched Rudd read the speech live on television. Thousands of indigenous Australians converged on the capital, filling the House of Representatives visitors' gallery and spilling outside. As Australians, we are largely unused to witnessing first-hand the making of history, unless it comes from the blade of a cricket bat or the lunging head of a horse. Here we would be spectators to something as intangible, yet as elementary, as an apology from one group of human beings to another. Here, at nine o'clock on a Wednesday morning in late summer, a prime minister would open the 42nd Parliament of the Commonwealth by attempting to build a metaphorical bridge between white and black Australians using words alone. -

2012 Annual Report 2012 Rna Rna Royal Queensland Food and Wine Show

The RoyAl NAtional AgRicultural and iNdustRiAl AssociAtioN of QueeNsland annual report 2012 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2012 RNA PRESIDENT’S REPORT PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2 Change brings RNA Showgrounds Regeneration Project opportunity. Almost a decade ago we set out to HIGHLIGHTS 3 2012 was a year build on our strong foundation with two of significant MISSION, VISION AND VALUES 4 critical goals in mind—to keep the Royal change for The Queensland Show (Ekka) at its birthplace, RNA CORPORATE 6 Royal National the RNA Showgrounds, and cement Agricultural the long-term financial viability of the THROUGH THE YEARS 10 and Industrial association so that the RNA can continue Association of Queensland (RNA) to fulfil its charter. ROYAL QUEENSLAND SHOW / and a year where we pursued every EKKA 14 opportunity. The RNA’s regeneration project resulted. RNA SHOWGROUNDS 20 We continued with our efforts to unlock Approved in November 2010 with the ROYAL INTERNATIONAL the potential of the RNA Showgrounds ground broken in April the following year, CONVENTION CENTRE 22 for the benefit of all stakeholders and the 2012 focused on redeveloping the iconic community at large, while staying true Industrial Pavilion to create the world- 2 ROYAL QUEENSLAND to the association’s charter. class convention centre. FOOD AND WINE SHOW 26 Your association made significant Other stage one works undertaken DIGITAL INTERACTION 28 headway on the $2.9 billion RNA during the year included the removal of OFFICE BEARERS 31 Showgrounds Regeneration Project— several buildings allowing construction the largest Brownfield development of the Plaza fronting the convention IN MEMORIAM 32 of its kind in Australia. -

Robson on Toowoomba Mosque by Frank Robson

SBS report by Frank Robson on Toowoomba Mosque https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/life/feature/garden-city-burning-who-set-mosque-fire By Frank Robson Grainy CCTV shows the man police believe set fire to a mosque – twice. Who is the arsonist targeting Toowoomba’s Muslim community? Published August 3, 2016. Reading time: 20 mins On a cold and starry night during the holy month of Ramadan, wind whistles through the fire-damaged timbers of Toowoomba’s Garden City Mosque. Once a Christian church, the brick and timber chapel with its distinctive arched roof became the city’s first mosque amid much rejoicing early in 2014. CCTV released by Queensland Police shows the suspected arsonist. At the time, there were predictions “10,000 rednecks” would oppose the mosque, set on a large corner block in a leafy residential suburb near the CBD. But it didn’t happen. Apart from some neighbours' complaints over parking problems, and a few obscenities shouted from passing vehicles, peace and harmony prevailed in the Darling Downs city once described as “the buckle on Queensland’s Bible belt”. Then, in January and April last year, the mosque in West Street, Harristown, was hit by two still unsolved arson attacks. The first, in a wooden outbuilding, did little damage. But the second effectively destroyed the interior of the mosque, rendering it unusable. Both fires were deliberately lit between 1am and 2am, probably by the same person, but despite an ongoing investigation, police admit they’re no closer to making an arrest than when they began. Imam of Garden City Mosque, Abdul Kader, explains what happened. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

30 March 2015 ASX Announcement Re: General meeting of Warrnambool Cheese and Butter Factory Company Holdings Limited (Company) and Proxy Form Please find attached the following documents: Notice of General Meeting and Explanatory Memorandum; and Proxy Form. Yours faithfully, Paul Moloney Company Secretary For personal use only Warrnambool Cheese and Butter Factory Company Holdings Limited 5331 Great Ocean Road, Allansford Victoria 3277 Australia Telephone: (03) 5565 3100 Facsimile: (03) 5565 3156 Website: wcbf.com.au ACN 071 945 232 ABN 15 071 945 232 Notice of general meeting and explanatory memorandum Warrnambool Cheese and Butter Factory Company Holdings Limited ACN 071 945 232 Date: Thursday, 30 April 2015 Time: 8.00 am (Melbourne time) Place: Clayton Utz Level 18, 333 Collins Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000 THE DIRECTORS UNANIMOUSLY RECOMMEND THAT NON-ASSOCIATED SHAREHOLDERS VOTE IN FAVOUR OF THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION. THE INDEPENDENT EXPERT, GRANT THORNTON CORPORATE FINANCE PTY LTD ACN 003 265 987, AFSL 247140, HAS CONCLUDED THAT THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION IS FAIR AND REASONABLE TO NON-ASSOCIATED SHAREHOLDERS. This is an important document and requires your immediate attention. You should read the whole of this document before you decide whether and how to vote on the Resolution in the Notice of Meeting. If you are in doubt as to what you should do, please consult your financial or professional adviser. For personal use only CONTENTS Chairman's Letter Page 3 Notice of general meeting Page 4 Instructions for voting and proxies Page 5 Explanatory Memorandum Page 8 Independent Expert's Report Page 12 Key dates Date of this document Thursday, 26 March 2015 Proxy form to be received no later than Tuesday, 28 April 2015 at 8.00 am (Melbourne time) General Meeting Thursday, 30 April 2015 at 8.00 am (Melbourne time) DISCLAIMER AND IMPORTANT NOTICES Important This booklet is an important document. -

NSW Nurses and Midwives Association Professional Day: Diversity in Healthcare 19 July

NSW Nurses and Midwives Association Professional Day: Diversity in Healthcare 19 July http://www.nswnma.asn.au/professional-day-2016/ 1. Introduction Good morning colleagues, and thank you so much to the organisers for this opportunity to talk to you today about some matters that are very close to my heart. Nursing and Midwifery history, acceptance of a shared history, racism and cultural safety and how the professions can make amends. I am proud Nurrunga Kaurna woman -- which means I am from the York Peninsula in South Australia, more specifically Point Pearce mission. I would like to begin by paying my respects to the Traditional Custodians of this land the Darrak people and to Elders past and present, and to future emerging generations. I would also like to acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander colleagues who are here today, including members of the Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives, the organisation which I have the great privilege to lead. I would also like to acknowledge all the Indigenous nurses and midwives who have gone before us; I like to introduce people to May Yarrowick, an Aboriginal nurse who trained in obstetric nursing in Sydney in 1903. Just take a moment to imagine what it must have been like for her, to work as an Aboriginal nurse in that era, - treating and caring for both Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal peoples. And she may well be our first Aboriginal woman qualified in western nursing. We now have more than 3,000 Indigenous Nurses and Midwives working across this great country. -

3285-Aamar0614.Pdf

Celebrating Issue No. 3285 Years of service to the The community Published Allora by Dairy Brokers Australia Pty. Ltd., at the AdvertiserOffice, 53 Herbert Street, Allora, Q. 4362 Issued Weekly as an Advertising Medium to the people of Allora and surrounding Districts. Your FREE Local Ph 07 4666 3128 - Fax 07 4666 3822 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web www.alloraadvertiser.com THURSDAY, 6th MARCH 2014 MARKET DAY SPECIALS FRIDAY, 7th MARCH 2014 SUPER ONE DAY ONLY PRICES! Fruit & Veg, FRESH from the ✔ Omo Laundry Powder 1kg ......... ✔ Lettuce ........................ $1.99 ea BRISBANE MARKETS PLUS… ......................................... $5.99 ✔ Avocados .................... $1.69 ea ✔ Kraft Cheese Colby Block 1kg ... ✔ Nescafe Mild Roast 250g $7.99 ✔ Pumpkin Jap ...................89¢ kg ......................................... $8.00 ✔ ✔ Small Watermelon ..........99¢ kg Arnotts Chocolate Tim Tam ✔ Dairy Farmers Yoghurt 600g ..... ✔ Tomatoes .....................$2.49 kg 200g ................................. $1.99 ......................................... $3.75 ✔ Zammit Leg Ham .......$10.99 kg ✔ Kleenex Toilet Rolls 8pk .. $3.99 ✔ Coon Cheese Tasty Block 1kg ... ✔ ✔ Golden Circle Drink 6x250mL .... ......................................... $8.00 2 x Regular BBQ Chickens ........ ......................................... $2.50 ✔ Nanna Apple Crumble 550g ...... ....................................... $14.00 ✔ Golden Circle Cordial 2L . $2.89 ......................................... $2.99 ✔ Primo Middle Bacon ........ $8.99 -

The Process and Importance of Writing Aboriginal Fiction for Young Adult Readers Exegesis Accompanying the Novel “Calypso Summers”

The process and importance of writing Aboriginal fiction for young adult readers Exegesis accompanying the novel “Calypso Summers” Jared Thomas Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities Discipline of English University of Adelaide September 2010 Dedication For the Nukunu and all Indigenous people in our quest to live, reclaim, document and maintain culture. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT...................................................................................................... 4 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ..................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 7 PART A: ABORIGINAL REPRESENTATION AND NEGOTIATING PROTOCOL ......................................................................................................................... 9 Representation of Aboriginal people and culture in film and fiction................ 10 Who can represent Aboriginal Australia and how? ........................................ 13 Identity and its impact on engagement with protocols ................................... 21 Writing in accord with Aboriginal cultural protocols ....................................... -

Holland Park Australia

PO Box 5151 Mt Gravatt East 4122 Meetings: 9.30 a.m. to 11.45 a.m. every third Thursday of the month. Venue: Newnham Hotel, Newnham Rd, Upper Mt Gravatt https://www.probussouthpacific.org/microsites/hollandparkcentral/Home [email protected] Editor: [email protected] January 2021 Issue No.149 The HP Source – It’s a bottler! bottler!bbbbbbbbottler!bottbottlerbottler! Jill’s Jottings It’s three days before Christmas and I still have two gifts to buy and another two to post to America which, of course, will not arrive in time. Fortunately, my daughter is understanding of the time delay. Our Christmas celebrations were very much enjoyed by all who attended. Many thanks to Bill and Lynne for their organisation. Our thanks to the Newnham hotel whose staff did an outstanding job of decorating the room which set the mood as soon as we entered. The meal lived up to our expectations and the entertainment was very good. What a difficult year it has been for people around the world. This nasty virus has caused grief and loss for so many families around the world. We are truly blessed here in Australia. If we put it in perspective, approximately one-third of the world’s population was infected with the Spanish flu in 1918. That equated to about 500 million people infected, and it is estimated between 20- 50 million people died world-wide. Did you know the Spanish flu probably did not originate in Spain? It has been suggested that France, Britain, and China were the source of the infection, and also the USA, as the first documented case was reported at a military base in Kansas in early 1918. -

Australia's Coon Cheese to Change Name in Effort to Help 'Eliminate Racism'

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Australia’s Coon cheese to change name in effort to help ‘eliminate racism' Company has previously resisted calls to change branding, saying it was named after American cheesemaker Edward William Coon Australian cheese brand Coon will change its name after Black Lives Matter protests once again put the focus on the brand and a campaign stating it was offensive to Indigenous Australians. Photograph: Bianca de Marchi/AAP Elias Visontay 24 Jul 2020 The Australian cheese brand Coon will change its name to help “eliminate racism” following a campaign stating the product name was offensive to Indigenous Australians. Friday’s announcement by Saputo, the dairy company that owns Coon, “to retire the Coon brand name”, comes after a decades-long effort to rename the cheese, including an unsuccessful 1999 complaint to the Australian Human Rights Commission from Indigenous activist Dr Stephen Hagan. Hagan told the Guardian on Friday the decision was “a total vindication of 20 years of campaigning”. Coon, along with other businesses, artists and cultural symbols, has come under fresh scrutiny over racial connotations in recent months as the Black Lives Matter movement gained momentum in Australia. 2 The brand, which was first sold in 1935, has long resisted calls to change its name, defending its historical decision to name the cheese after American cheesemaker Edward William Coon, who, according to the brand’s website, “patented a unique ripening process” used to make the dairy product. A new name for Coon has not yet been decided, but Saputo said it was “working to develop a new brand name that will honour the brand-affinity felt by our valued consumers while aligning with current attitudes and perspectives”.