Readerjun2009.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impartiality in Opinion Content (July 2008)

Quality Assurance Project 5: Impartiality (Opinion Content) Final Report July 2008 Advise. Verify. Review ABC Editorial Policies Editorial Policies The Editorial Policies of the ABC are its leading standards and a day-to-day reference for makers of ABC content. The Editorial Policies – • give practical shape to statutory obligations in the ABC Act; • set out the ABC’s self-regulatory standards and how to enforce them; and • describe and explain to staff and the community the editorial and ethical principles fundamental to the ABC. The role of Director Editorial Policies was established in 2007 and comprises three main functions: to advise, verify and review. The verification function principally involves the design and implementation of quality assurance projects to allow the ABC to assess whether it is meeting the standards required of it and to contribute to continuous improvement of the national public broadcaster and its content. Acknowledgements The project gained from the sustained efforts of several people, and the Director Editorial Policies acknowledges: Denis Muller, Michelle Fisher, Manager Research, and Jessica List, Executive Assistant. Thanks also to Ian Carroll and John Cameron, respectively the Directors of the Innovation Division and the News Division, and to their senior staff, whose engagement over the details of editorial decision-making gave the project layers that an assessment of this sort usually lacks. This paper is published by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation © 2008 ABC For information about the paper, please contact: Director Editorial Policies ABC Southbank Centre GPO Box 9994 Melbourne VIC 3001 Phone: +61 3 9626 1631 Email: [email protected] QA Project 05 – Final Report July 2008 ABC Editorial Policies Foreword Opinion and impartiality – are there any other words which, when paired, are more fraught for a public broadcaster? Is any other pair of words more apparently paradoxical? Opinion content is commissioned or acquired by the ABC to provide a particular perspective or point of view. -

Sugar Ray's Bitterness

Sugar Ray's bitterness By Greg Roberts Sydney Morning Herald 5 October 2002 Rivalry over government funding and political power has spilled over into a nasty brawl in outback Queensland. Greg Roberts reports. ONE of Australia's most powerful Aboriginal leaders points to a patch of dry mulga scrub outside the south-west Queensland town of Charleville. "That's where I grew up as a kid; that's where the tin shed was," says "Sugar" Ray Robinson, deputy chairman of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC). "It had a dirt floor; eight of us lived there. We carted water in a bucket from a tap every day. We ate bread and water with sugar sprinkled on it. There wasn't a day went past that I wasn't hungry." Robinson, 56, has come a long way. Today he heads the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services Secretariat and 13 other indigenous bodies. A powerbroker in ATSIC, he is a constant thorn in the side of the commission chairman, Geoff Clark. Robinson predicts that after the October 19 ATSIC elections, Clark will no longer be chairman. "Geoff Clark has a problem and the problem is he is not going to get in as chairman while I'm there," he booms in his trademark gravelly voice. "He hasn't got the numbers. He knows that if he's ever to get back as chairman, I'm his biggest threat." Robinson insists he does not covet the top job. Clark infuriated Robinson recently when he called for an investigation into allegations against his deputy in a series of articles in Brisbane's The Courier-Mail newspaper. -

Mcondon.Apology.Feb0

The Hardest Word Author: Matthew Condon QWeekend Magazine (Brisbane, Australia) - Courier Mail Saturday, February 7, 2009 Was Kevin Rudd's "sorry" speech an act of heartfelt reconciliation or an empty gesture? One year on, Qweekend asks 14 indigenous Australians. To read it now, one year on, it no longer contains the fire glow of its initial delivery, nor does it make its way so directly to the human heart, removed from its astonishing emotional context on that morning of February 13 last year. But Prime Minister Kevin Rudd's now famous "sorry" speech to Australia's Stolen Generations, his first major act of parliamentary business as leader of the nation, remains a significant specimen of political rhetoric. Flat on the page it continues to show life because we can still readily connect it to the memory of that cloudy Canberra day, and how the nation stopped in the manner of great sporting events or great tragedy. More than 1.3 million Australians watched Rudd read the speech live on television. Thousands of indigenous Australians converged on the capital, filling the House of Representatives visitors' gallery and spilling outside. As Australians, we are largely unused to witnessing first-hand the making of history, unless it comes from the blade of a cricket bat or the lunging head of a horse. Here we would be spectators to something as intangible, yet as elementary, as an apology from one group of human beings to another. Here, at nine o'clock on a Wednesday morning in late summer, a prime minister would open the 42nd Parliament of the Commonwealth by attempting to build a metaphorical bridge between white and black Australians using words alone. -

Robson on Toowoomba Mosque by Frank Robson

SBS report by Frank Robson on Toowoomba Mosque https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/life/feature/garden-city-burning-who-set-mosque-fire By Frank Robson Grainy CCTV shows the man police believe set fire to a mosque – twice. Who is the arsonist targeting Toowoomba’s Muslim community? Published August 3, 2016. Reading time: 20 mins On a cold and starry night during the holy month of Ramadan, wind whistles through the fire-damaged timbers of Toowoomba’s Garden City Mosque. Once a Christian church, the brick and timber chapel with its distinctive arched roof became the city’s first mosque amid much rejoicing early in 2014. CCTV released by Queensland Police shows the suspected arsonist. At the time, there were predictions “10,000 rednecks” would oppose the mosque, set on a large corner block in a leafy residential suburb near the CBD. But it didn’t happen. Apart from some neighbours' complaints over parking problems, and a few obscenities shouted from passing vehicles, peace and harmony prevailed in the Darling Downs city once described as “the buckle on Queensland’s Bible belt”. Then, in January and April last year, the mosque in West Street, Harristown, was hit by two still unsolved arson attacks. The first, in a wooden outbuilding, did little damage. But the second effectively destroyed the interior of the mosque, rendering it unusable. Both fires were deliberately lit between 1am and 2am, probably by the same person, but despite an ongoing investigation, police admit they’re no closer to making an arrest than when they began. Imam of Garden City Mosque, Abdul Kader, explains what happened. -

NSW Nurses and Midwives Association Professional Day: Diversity in Healthcare 19 July

NSW Nurses and Midwives Association Professional Day: Diversity in Healthcare 19 July http://www.nswnma.asn.au/professional-day-2016/ 1. Introduction Good morning colleagues, and thank you so much to the organisers for this opportunity to talk to you today about some matters that are very close to my heart. Nursing and Midwifery history, acceptance of a shared history, racism and cultural safety and how the professions can make amends. I am proud Nurrunga Kaurna woman -- which means I am from the York Peninsula in South Australia, more specifically Point Pearce mission. I would like to begin by paying my respects to the Traditional Custodians of this land the Darrak people and to Elders past and present, and to future emerging generations. I would also like to acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander colleagues who are here today, including members of the Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives, the organisation which I have the great privilege to lead. I would also like to acknowledge all the Indigenous nurses and midwives who have gone before us; I like to introduce people to May Yarrowick, an Aboriginal nurse who trained in obstetric nursing in Sydney in 1903. Just take a moment to imagine what it must have been like for her, to work as an Aboriginal nurse in that era, - treating and caring for both Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal peoples. And she may well be our first Aboriginal woman qualified in western nursing. We now have more than 3,000 Indigenous Nurses and Midwives working across this great country. -

The Process and Importance of Writing Aboriginal Fiction for Young Adult Readers Exegesis Accompanying the Novel “Calypso Summers”

The process and importance of writing Aboriginal fiction for young adult readers Exegesis accompanying the novel “Calypso Summers” Jared Thomas Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities Discipline of English University of Adelaide September 2010 Dedication For the Nukunu and all Indigenous people in our quest to live, reclaim, document and maintain culture. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION................................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT...................................................................................................... 4 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY ..................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 7 PART A: ABORIGINAL REPRESENTATION AND NEGOTIATING PROTOCOL ......................................................................................................................... 9 Representation of Aboriginal people and culture in film and fiction................ 10 Who can represent Aboriginal Australia and how? ........................................ 13 Identity and its impact on engagement with protocols ................................... 21 Writing in accord with Aboriginal cultural protocols ....................................... -

Australia's Blackest Sporting Moments: the Top 100

Australia's Blackest Sporting Moments: The Top 100 Australia's Blackest Sporting Moments: The Top 100; 2006; Ngalga Warralu Publishing Pty Ltd, 2006; Stephen Hagan; 1921212004, 9781921212000 Internationally renowned academic, political advocate and award winning author, Stephen Hagan reveals the darker side of racism in sport and exposes Australian ugly underbelly. Australia's Blackest Sporting Moments: The Top 100 is a painfully easy read of incidents of racism in Australian sport. Hagan has cleverly used a diverse range of professional non-Indigenous contributors to review 10 separate articles and in doing so adds balanced perspectives of this regrettable past. The contrast in styles and interpretations of the 100 incidents is appealing in its simplicity. The book has 46 cartoons illustrating various incidents in humorous way. Hagan takes the reader on a journey not many of them would like to go. However the compelling read of iconic figures identified in his book is so profound that the reader's initial anxiety of 'not another black arm band book?' is quickly relieved. It is demonstrably clear from Henry Lawson's 1908 remarks of African American Jack Johnson defeat of Tommy Burns 'for a nigger smacked your face' to Yvonne Goolagong receiving abuse 'That's the first time I've ever been beaten by a nigger' to the infamous Queensland Cricket Captain, Jimmy Maher's, comments "full as a coon's Valiant'', that the author's extensive research has not missed an incident of note since the time of colonisation. Hagan's deliberate inclusion of Indigenous perpetrators of racial abuse gives creditability to an otherwise bias book. -

Walking My Path

Walking My Path An Autoethnographic Study of Identity Davina B Woods Dip. of Teaching NBCAE, B. Ed QUT, Grad. Cert Aboriginal Studies UniSA, MA Monash, Grad. Cert. Ter. Ed. VU Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts and Education Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia June 2018 1 | P a g e Abstract ‘Walking My Path: An Autoethnographic Study of Identity’ is a doctoral thesis written in first person narrative about my search for my ancestral country in Far North Queensland. Incorporating both physical walking on country and metaphorical walking of trauma trails (Atkinson 2002) the story of my matrilineal Grandfather’s childhood builds on Shirleen Robinson’s (2008) ‘Something like Slavery?’. Enabling me to explore First-Nations philosophical concepts, I explain how I practise this philosophy inside my First-Nations family and community in the 21st century. Embedding my research in Indigenous Standpoint Theory and gathering the data, using a methodological net that includes yarning and dadirri, I am honouring First-Nations peoples. Finding that much of the data was distressing I have developed Creative Healing Inquiry (CHI), a process that supports the rebalancing of an individual’s psyche. CHI also makes the thesis both intertextual and serves as a mechanism that acknowledges multiliteracies. The Cusp Generation, children born between the end of WWII (1945) and Australia’s withdrawal from Vietnam (1972), are the people I propose would benefit most from public pedagogy that tells of Australia’s history. With the release of the Australian Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report in 1991 and the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s Bringing Them Home report in 1997; my work makes shared history more relevant through its direct connection with actual people rather than abstract statistics. -

Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander

NOVEMBER 2007 ■ VOL 4 ■ ISSUE 2 ABORIGINAL & nFROMe THE NwATIONAL s TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIA Going home to Kinchella Tayenebe NAIDOC 50th Anniversary Who You Callin’ Urban? Forum 2 Message from the Director of the National Museum of Australia MESSAGE FROM THE 3 Message from the Principal Advisor (Indigenous) MESSAGE FROM THE MESSAGE FROM to the Director, and Senior Curator PRINCIpAL ADVISOR THE ABORIGINAL AND DIRECTOR OF THE (INDIGENOUS) TO 3 Message from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER Islander Program Director NATIONAL MUSEUM THE DIRECTOR, AND OF AUSTRALIA PROGRAM DIRECTOR 4 Mates SENIOR CURATOR 5 Celebrating NAIDOC’s 50th anniversary, Photo: Dean McNicoll by Barbara Paulson 6 NAIDOC Week celebrations at the Museum, by Helena Bezzina I would like to acknowledge the Ngambri and Welcome. We acknowledge the traditional custodians of this Hi, and welcome to this issue. On behalf of ATSIP 8 70% Urban, by Barbara Paulson Ngunnawal peoples as traditional custodians of the lands upon area, the Ngambri and Ngunnawal peoples, and others who are now I’d like to acknowledge the Ngambri and Ngunnawal peoples, both as 9 Who You Callin’ Urban?, by Margo Neale which the National Museum is built. part of our Indigenous Canberra community. the traditional owners of the Canberra region and as valued friends of the Museum. 10 Going back home, by Jay Arthur There are always exciting things happening at the Museum. In the last issue, I outlined a number of initiatives that would help Contents 11 Martu community members visit the Museum, The celebration of NAIDOC Week’s 50th anniversary and us get things moving at a faster and more sustainable pace in the Life for the ATSIP team continues to be busy. -

“To Be Part of an Aboriginal Dream of Self-Determination” Aboriginal Activism in Redfern in the 1970S

“To be Part of an Aboriginal Dream of Self-Determination” Aboriginal activism in Redfern in the 1970s Johanna Perheentupa A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Languages Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences August 2013 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. Date …………………………………………….............. COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ‘I hereby grant the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or part in the University libraries in all forms of media, now or here after known, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I retain all proprietary rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. -

Sports and Recreation

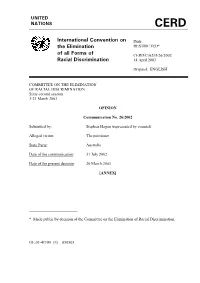

SPORTS AND RECREATION III. JURISPRUDENCE CERD · Hagan v. Australia (26/2002), CERD, A/58/18 (20 March 2003) 139 (CERD/C/62/D/26/2002) at paras. 1, 2.1, 7.2, 7.3 and 8. 1. The petitioner, Stephen Hagan, is an Australian national, born in 1960, with origins in the Kooma and Kullilli tribes of south-western Queensland. He alleges to be a victim of a violation by Australia of articles 2, in particular, paragraph 1 (c); 4; 5, paragraphs d (i) and (ix), e (vi) and f; 6 and 7 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. He is represented by counsel. 2.1 In 1960, the grandstand of an important sporting ground in Toowoomba, Queensland, where the author lives, was named the “E.S. ‘Nigger’ Brown Stand”, in honour of a well-known sporting and civic personality, Mr. E.S. Brown. The word “nigger” (“the offending term”) appears on a large sign on the stand. Mr. Brown, who was also a member of the body overseeing the sports ground and who died in 1972, was of white Anglo-Saxon extraction who acquired the offending term as his nickname, either “because of his fair skin and blond hair or because he had a penchant for using ‘Nigger Brown’ shoe polish”. The offending term is also repeated orally in public announcements relating to facilities at the ground and in match commentaries. ... 7.2 The Committee has taken due account of the context within which the sign bearing the offending term was originally erected in 1960, in particular the fact that the offending term, as a nickname probably with reference to a shoeshine brand, was not designed to demean or diminish its bearer, Mr. -

International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

70+6'& 0#6+105 %'4& +PVGTPCVKQPCN%QPXGPVKQPQP Distr. VJG'NKOKPCVKQP RESTRICTED* QHCNN(QTOUQH CERD/C/62/D/26/2002 4CEKCN&KUETKOKPCVKQP 14 April 2003 Original: ENGLISH COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION Sixty-second session 3-21 March 2003 OPINION Communication No. 26/2002 Submitted by: Stephen Hagan (represented by counsel) Alleged victim: The petitioner State Party: Australia Date of the communication: 31 July 2002 Date of the present decision: 20 March 2003 [ANNEX] * Made public by decision of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. GE.03-41199 (E) 050503 CERD/C/62/D/26/2002 page 2 Annex OPINION OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE ELIMINATION OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION UNDER ARTICLE 14 OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION ON THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION sixty-second session concerning Communication No. 26/2002 Submitted by: Stephen Hagan (represented by counsel) Alleged victim: The petitioner State party: Australia Date of the communication: 31 July 2002 The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, established under article 8 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Meeting on 20 March 2003, Adopts the following: Opinion 1. The petitioner, Stephen Hagan, is an Australian national, born in 1960, with origins in the Kooma and Kullilli Tribes of South Western Queensland. He alleges to be a victim of a violation by Australia of articles 2, in particular, paragraph 1 (c); 4; 5, paragraphs d (i) and (ix), e (vi) and f; 6 and 7 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.