Volume 61 — Issue 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Environment Is All Rights: Human Rights, Constitutional Rights and Environmental Rights

Advance Copy THE ENVIRONMENT IS ALL RIGHTS: HUMAN RIGHTS, CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS RACHEL PEPPER* AND HARRY HOBBS† Te relationship between human rights and environmental rights is increasingly recognised in international and comparative law. Tis article explores that connection by examining the international environmental rights regime and the approaches taken at a domestic level in various countries to constitutionalising environmental protection. It compares these ap- proaches to that in Australia. It fnds that Australian law compares poorly to elsewhere. No express constitutional provision imposing obligations on government to protect the envi- ronment or empowering litigants to compel state action exists, and the potential for draw- ing further constitutional implications appears distant. As the climate emergency escalates, renewed focus on the link between environmental harm and human harm is required, and law and policymakers in Australia are encouraged to build on existing law in developing broader environmental rights protection. CONTENTS I Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 II Human Rights-Based Environmental Protections ................................................... 8 A International Environmental Rights ............................................................. 8 B Constitutional Environmental Rights ......................................................... 15 1 Express Constitutional Recognition .............................................. -

Impartiality in Opinion Content (July 2008)

Quality Assurance Project 5: Impartiality (Opinion Content) Final Report July 2008 Advise. Verify. Review ABC Editorial Policies Editorial Policies The Editorial Policies of the ABC are its leading standards and a day-to-day reference for makers of ABC content. The Editorial Policies – • give practical shape to statutory obligations in the ABC Act; • set out the ABC’s self-regulatory standards and how to enforce them; and • describe and explain to staff and the community the editorial and ethical principles fundamental to the ABC. The role of Director Editorial Policies was established in 2007 and comprises three main functions: to advise, verify and review. The verification function principally involves the design and implementation of quality assurance projects to allow the ABC to assess whether it is meeting the standards required of it and to contribute to continuous improvement of the national public broadcaster and its content. Acknowledgements The project gained from the sustained efforts of several people, and the Director Editorial Policies acknowledges: Denis Muller, Michelle Fisher, Manager Research, and Jessica List, Executive Assistant. Thanks also to Ian Carroll and John Cameron, respectively the Directors of the Innovation Division and the News Division, and to their senior staff, whose engagement over the details of editorial decision-making gave the project layers that an assessment of this sort usually lacks. This paper is published by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation © 2008 ABC For information about the paper, please contact: Director Editorial Policies ABC Southbank Centre GPO Box 9994 Melbourne VIC 3001 Phone: +61 3 9626 1631 Email: [email protected] QA Project 05 – Final Report July 2008 ABC Editorial Policies Foreword Opinion and impartiality – are there any other words which, when paired, are more fraught for a public broadcaster? Is any other pair of words more apparently paradoxical? Opinion content is commissioned or acquired by the ABC to provide a particular perspective or point of view. -

The Complete Book of Cheese by Robert Carlton Brown

THE COMPLETE BOOK OF CHEESE BY ROBERT CARLTON BROWN Chapter One I Remember Cheese Cheese market day in a town in the north of Holland. All the cheese- fanciers are out, thumping the cannon-ball Edams and the millstone Goudas with their bare red knuckles, plugging in with a hollow steel tool for samples. In Holland the business of judging a crumb of cheese has been taken with great seriousness for centuries. The abracadabra is comparable to that of the wine-taster or tea-taster. These Edamers have the trained ear of music-masters and, merely by knuckle-rapping, can tell down to an air pocket left by a gas bubble just how mature the interior is. The connoisseurs use gingerbread as a mouth-freshener; and I, too, that sunny day among the Edams, kept my gingerbread handy and made my way from one fine cheese to another, trying out generous plugs from the heaped cannon balls that looked like the ammunition dump at Antietam. I remember another market day, this time in Lucerne. All morning I stocked up on good Schweizerkäse and better Gruyère. For lunch I had cheese salad. All around me the farmers were rolling two- hundred-pound Emmentalers, bigger than oxcart wheels. I sat in a little café, absorbing cheese and cheese lore in equal quantities. I learned that a prize cheese must be chock-full of equal-sized eyes, the gas holes produced during fermentation. They must glisten like polished bar glass. The cheese itself must be of a light, lemonish yellow. Its flavor must be nutlike. -

Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?

Fordham Law Review Volume 86 Issue 6 Article 12 2018 Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete? Kevin Brown Indiana University Maurer School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Brown, Evolution of the Racial Identity of Children of Loving: Has Our Thinking About Race and Racial Issues Become Obsolete?, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 2773 (2018). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol86/iss6/12 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLUTION OF THE RACIAL IDENTITY OF CHILDREN OF LOVING: HAS OUR THINKING ABOUT RACE AND RACIAL ISSUES BECOME OBSOLETE? Kevin Brown* It is a special honor for me to have this opportunity to discuss the U.S. Supreme Court’s opinion in Loving v. Virginia1 at a Symposium held in honor of its fiftieth anniversary. I served on the panel entitled “The Children of Loving,”2 which for me has two connotations. First, as an African American who married a white woman twenty years after the decision, I am a child of Loving in the sense that I was in an interracial marriage. But as a father of two black-white biracial children, I am also a father of two Loving children. -

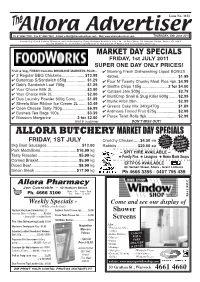

Allora Advertiser Ph 07 4666 3128 - Fax 07 4666 3822 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web THURSDAY, 30Th June 2011

Issue No. 3152 The Allora Advertiser Ph 07 4666 3128 - Fax 07 4666 3822 - E-Mail [email protected] - Web www.alloraadvertiser.com THURSDAY, 30th June 2011 Printed by David Patrick Gleeson and Published by Dairy Brokers Australia Pty. Ltd., at the Office, 53 Herbert Street, Allora, Q. 4362 Issued Weekly as an Advertising Medium to the people of Allora and surrounding Districts. MARKET DAY SPECIALS FRIDAY, 1st JULY 2011 SUPER ONE DAY ONLY PRICES! Fruit & Veg, FRESH from the BRISBANE MARKETS PLUS… ✔ Morning Fresh Dishwashing Liquid BONUS ✔ 2 Regular BBQ Chickens .................... $13.98 450mL .................................................... $1.99 ✔ Buttercup S/Sandwich 650g .................. $1.29 ✔ Four N' Twenty Chunky Meat Pies 4pk . $4.99 ✔ Deb's Sandwich Loaf 700g ................... $1.29 ✔ Smiths Chips 185g ....................... 2 for $4.00 ✔ Your Choice Milk 3L .............................. $3.00 ✔ Cottees Jam 500g ................................. $2.79 ✔ Your Choice Milk 2L .............................. $2.00 ✔ MultiCrop Snail & Slug Killer 600g ........ $2.99 ✔ Duo Laundry Powder 500g Conc. ........ $1.89 ✔ Multix Alfoil 20m .................................... $2.99 ✔ Streets Blue Ribbon Ice Cream 2L ....... $3.49 ✔ Greens Cake Mix 340g/470g ................ $1.89 ✔ Coon Cheese Tasty 750g ...................... $6.99 ✔ ✔ Bushels Tea Bags 100s ......................... $3.39 Ardmona Tinned Fruit 825g ................... $2.99 ✔ Blossom Margarine ...................... 2 for $2.00 ✔ Purex Toilet Rolls 9pk -

Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology Versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 21:31 Atlantis Critical Studies in Gender, Culture & Social Justice Études critiques sur le genre, la culture, et la justice Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta Volume 39, numéro 2, 2018 Résumé de l'article This article explores how race and gender become distinguished from each URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064075ar other in contemporary scholarly and activist debates on the comparison DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar between transracialism and transgender identities. The article argues that transracial-transgender distinctions often reinforce divides between Aller au sommaire du numéro autological (self-determined) and genealogical (inherited) aspects of subjectivity and obscure the constitution of this division through modern technologies of power. Éditeur(s) Mount Saint Vincent University ISSN 1715-0698 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Dutta, A. (2018). Allegories of Gender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism. Atlantis, 39(2), 86–98. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064075ar All Rights Reserved © Mount Saint Vincent University, 2018 Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ Special Section: Research Allegories ofGender: Transgender Autology versus Transracialism Aniruddha Dutta is an Assistant Professor in the de- Introduction: Two Scenes ofTransgender partments of Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies Recognition and Asian and Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Iowa. -

Checking the Checking Value in the Teapot Dome Scandal

Communication Law Review Volume 15, Issue 2 (2015) Checking the Checking Value in the Teapot Dome Scandal David R. Dewberry, Ph.D. Rider University This article examines the history of journalism in the initial reporting of the Teapot Dome scandal to argue that the press falls short in fulfilling the checking value of the First Amendment. Similar arguments have been made about the press in other major scandals (e.g., Watergate, Iran-Contra, etc.). But this article exclusively focuses on the key journalistic agents in Teapot Dome including Frederick G. Bonfils and H. H. Tammen of the Denver Post, John C. Schaffer of the Rocky Mountain News, Carl Magee of New Mexico, and Paul Y. Anderson of the St. Louis Post- Dispatch, to demonstrate how they were more protagonists in the scandal, rather than members of the fourth estate. INTRODUCTION Political scandals reveal the worst and also the best of our democracy. The worst is that our public leaders have transgressed some norm or rule. The best is that the presence of scandals also suggests that a free press was able to enact what noted First Amendment scholar Vincent Blasi called “the checking value.” The checking value is “that free speech, a free press, and free assembly can serve in checking the abuse of power by public officials.”1 Furthermore, Blasi believes that free speech was a central and critical principle for the drafters of the First Amendment to “guard against breaches of trust by public officials.”2 As such, the American press is often dubbed the “watchdogs of democracy.”3 Given the press’s status in our democracy, its reputation sometimes reaches an undeserved mythic status. -

VOGUEKNITTINGLIVE.COM SC HEDULE Thursday, October 23 Registration: 3 P.M

VOGU Eknitting CHICAGO THE ULTIMATE KNITTING EVENT OCTOBER 24 –26 ,2014 • PALMER HOUSE HILTON HOTEL PRINTABLE BROCHURE NEW& INSPIRATIONAL KNITWORTHY HAND KNITTING PRODUCTS CLASSES & LECTURES! VOGUEKNITTINGLIVE.COM SC HEDULE Thursday, October 23 Registration: 3 p.m. –7 p.m. OF EVENTS Classroom Hours: 6 p.m. –9 p.m. Friday, October 24 VOGUEknitting Registration: 8 a.m. –7:30 p.m. 3-hour Classroom Hours: 9 a.m.–12 p.m., 2 p.m.–5 p.m., 6 p.m. –9 p.m. 2-hour Classroom Hours: 9 a.m.–11 a.m., 2 p.m.–4 p.m. Marketplace: 5:00 p.m. –8:30 p.m. Please refer to VogueknittingLIVE.com for complete details. Saturday, October 25 HOTEL INFORMATION Registration: 8 a.m. –6:30 p.m. Vogue Knitting LIVE will be held in 3-hour Classroom Hours: 9 a.m.–12 p.m., 2 p.m.–5 p.m., 6 p.m. –9 p.m. downtown Chicago at the luxurious 2-hour Classroom Hours: Palmer House Hilton Hotel, located 9 a.m.–11 a.m., 2 p.m.–4 p.m. near Millennium Park in the heart of Marketplace: 10 a.m. –6:30 p.m. the theater, financial, and shopping districts of downtown Chicago. The Palmer House Hilton Hotel is within walking distance of the Windy City’s Sunday, October 26 most famous museums, shopping,a government, and corporate buildings. Registration: 8 a.m. –3 p.m. 3-hour Classroom Hours: The Palmer House Hilton Hotel 9 a.m.–12 p.m., 2 p.m.–5 p.m. -

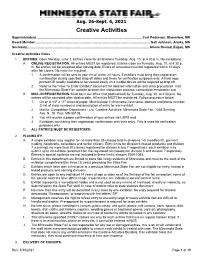

2021 Creative Activities Rules and Premiums

Aug. 26-Sept. 6, 2021 Creative Activities Superintendent..................................................................................................................... Curt Pederson, Shoreview, MN Board Member............................................................................................................................... Gail Johnson, Anoka, MN Secretary....................................................................................................................................... Arlene Restad, Eagan, MN Creative Activities Rules 1. ENTRIES. Open Monday, June 7. Entries close for all divisions Tuesday, Aug. 10, at 4:30 p.m. No exceptions. A. ONLINE REGISTRATION. All entries MUST be registered. Entries close on Tuesday, Aug. 10, at 4:30 p. m. No entries will be accepted after closing date. Errors or omissions must be registered within 10 days after fair closes. No entry fee required. 1. A confirmation will be sent to your email within 24 hours. Exhibitors must bring their registration confirmation during specified drop off dates and times for verification purposes only. A hard copy printed OR readily available to be viewed easily on a mobile device will be required at drop off. 2. Refer to the "How To Enter Exhibits" document for detailed information and entry procedures. Visit the Minnesota State Fair website to begin the registration process: competition.mnstatefair.org B. MAIL-IN REGISTRATION. Must be in our office (not postmarked) by Tuesday, Aug. 10, at 4:30 p.m. No entries will be accepted after closing date. All entries MUST be registered. Follow procedure below: 1. On an 8 1/2” x 11” sheet of paper. Must include 1) first name, last name, address and phone number; 2) list of class number(s) and description of entry for each exhibit. 2. Mail to: Competition Department - c/o: Creative Activities, Minnesota State Fair, 1265 Snelling Ave. N., St. Paul, MN 55108. -

Firstchoice Wusf

firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • noVemBer 2008 Rolling On the River with Burt Wolf Each week, WUSF TV/DT viewers join Burt Wolf, the genial host of Burt Wolf: Travels & Traditions, on his journeys around the world. Wolf has traveled by plane, train and automobile — but a river cruise is his favorite way to see Europe. This month, on November 12, during a two-hour special, Wolf takes us through the heart of Europe on three voyages along the winding Danube River. In Cruising the Danube, Wolf kicks off his leisurely journey in Budapest and then stops off at the fairy tale castles and hidden streets of Burt Wolf’s two- Bratislava, Dürnstein, Melk, Grein, Linz hour river cruise and Passau before coming full circle to Budapest. On his second expedition, special airs Christmas in Vienna, Wolf sets shore November 12 in Vienna, Austria, exploring ancient Christmas traditions (some edible!) at 8 p.m. and festivities at locations ranging WUSF TV/DT from the magnificent Habsburg castle to Vienna’s celebrated outdoor Channel 16 Christmas markets. On the last leg of the voyage, Austrian Monasteries, Wolf takes us inside the abbeys at Melk and Klosterneuburg — each a fascinating realm of history, tradition and treasure. Wolf concludes his journey with lunch at the restaurant of one of Europe’s most talented chefs. Intrigued? If you’re more than an armchair traveler, you can join Burt Wolf in July 2009 on a Danube River cruise with other WUSF friends. Find more information about this once-in-a-lifetime voyage inside! wusf: FIRST choice WUSF Public WUSF TV/DT Broadcasting: November Highlights A range of media choices WORLDFOCUS brings American audiences a deeper understanding WUSF 89.7 of the stories shaping the world provides NPR news and today. -

The Sword, April 2019

APRIL 2019 VOLUME 61 | ISSUE 1 EST. 1966 THE SWORD 5 The Muellor Report BY ETHAN LANGEMO 9 Earth Day 101: How to Make a Difference BY ALEXANDRIA GOSEN 14 CSP's New Sport Makes a Splash BY HARRY LIEN 19 Dancing the Semester Away Theatre and Dance Spotlight: Hannah Wudtke BY EDEN GARMAN Photography provided by Jan Puffer Pictured above is Hannah Wudtke, center of this month's theatre spotlight, more on the story on page 19 THIS IS NOT AN OFFICIAL CSP PUBLICATION AND DOES NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEWS OF THE ADMINISTRATION, FACULTY, OR STAFF. SPECIAL THANKS TO THE CONTRIBUTING SPONSORS. 1 The Sword Newspaper APRIL 2019 VOLUME 61 | ISSUE 1 NEWS EDITOR IN CHIEF CONCORDIA ST. PAUL’S OFFICIAL STUDENT NEWSPAPER SINCE 1966 Brooke Steigauf NEWS EDITOR Halle Martin Possible Border Closure Could Prove Costly SPORTS EDITOR BY VICTORIA TURCIOS BEN DIERS ARTS & VARIETY EDITOR rump’s administration has threatened to close the In an official statement, the Border Trade Alliance, North MARA GRAU u.s.–Mexico border, raising the concern of many and America’s premier advocate for cross-border trade, strongly OPINION EDITOR Tleaving officials of the Department of Homeland Security rejected President Trump’s call to close the border. “Discussion COURTNI HOLLOWAY alarmed and confused. The New York Times reported that in of closing the border creates uncertainty in the border economy a conversation with Kevin McAleenan (who Trump is about and puts at risk the commerce and travel that links the U.S PHOTO EDITOR to name acting secretary of homeland security), the president and Mexico, and that is responsible for millions of jobs.” It is VICTORIA TURCIOS urged him to close the Southwestern border. -

Day 127 - Monday 27Th July @ 11.04Pm I Feel Like I’Ve Been Punched in the Stomach

Day 127 - Monday 27th July @ 11.04pm I feel like I’ve been punched in the stomach. This may be not only the worst day of lockdown, but one of the worst days of my entire life. So, my friends are all seeing each other tomorrow whilst I’m being left out. I... feel so many emotions I’ve not felt in months. I thought they were my friends, apparently not. So, it’s short tonight, but for good reason. My friends are leaving me out and I’ve probably annoyed my best friend. Please fix this. Until tomorrow. Day 126 - Sunday 26th July @ 11.24pm Today wasn’t the greatest. We visited grandparents for a while which was nice to see them again. It’s strange seeing family more often since the change in lockdown. I played for a wee while this afternoon with friends but they all eventually moved on to competitive which made me feel not the best. I brought it up with a friend who seemed supportive but I really don’t know anymore. Please bring back the past couple of weeks. Until tomorrow. Day 125 - Saturday 25th July @ 11.50pm See yesterday’s entry: nothing has really changed today. I played with friends today which was awesome to be able to but I still can’t do competitive so... I feel slightly left out (of course unintentionally and it’s all on me). I just feel worried about playing it and messing up in front of friends. Thanks anyway for the great past couple of weeks so far! Until tomorrow.