Reconceptualizing the Inherent Distinctiveness of Product Design Trade Dress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOGUEKNITTINGLIVE.COM SC HEDULE Thursday, October 23 Registration: 3 P.M

VOGU Eknitting CHICAGO THE ULTIMATE KNITTING EVENT OCTOBER 24 –26 ,2014 • PALMER HOUSE HILTON HOTEL PRINTABLE BROCHURE NEW& INSPIRATIONAL KNITWORTHY HAND KNITTING PRODUCTS CLASSES & LECTURES! VOGUEKNITTINGLIVE.COM SC HEDULE Thursday, October 23 Registration: 3 p.m. –7 p.m. OF EVENTS Classroom Hours: 6 p.m. –9 p.m. Friday, October 24 VOGUEknitting Registration: 8 a.m. –7:30 p.m. 3-hour Classroom Hours: 9 a.m.–12 p.m., 2 p.m.–5 p.m., 6 p.m. –9 p.m. 2-hour Classroom Hours: 9 a.m.–11 a.m., 2 p.m.–4 p.m. Marketplace: 5:00 p.m. –8:30 p.m. Please refer to VogueknittingLIVE.com for complete details. Saturday, October 25 HOTEL INFORMATION Registration: 8 a.m. –6:30 p.m. Vogue Knitting LIVE will be held in 3-hour Classroom Hours: 9 a.m.–12 p.m., 2 p.m.–5 p.m., 6 p.m. –9 p.m. downtown Chicago at the luxurious 2-hour Classroom Hours: Palmer House Hilton Hotel, located 9 a.m.–11 a.m., 2 p.m.–4 p.m. near Millennium Park in the heart of Marketplace: 10 a.m. –6:30 p.m. the theater, financial, and shopping districts of downtown Chicago. The Palmer House Hilton Hotel is within walking distance of the Windy City’s Sunday, October 26 most famous museums, shopping,a government, and corporate buildings. Registration: 8 a.m. –3 p.m. 3-hour Classroom Hours: The Palmer House Hilton Hotel 9 a.m.–12 p.m., 2 p.m.–5 p.m. -

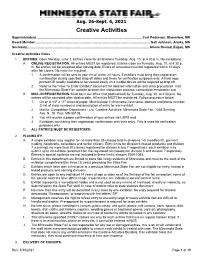

2021 Creative Activities Rules and Premiums

Aug. 26-Sept. 6, 2021 Creative Activities Superintendent..................................................................................................................... Curt Pederson, Shoreview, MN Board Member............................................................................................................................... Gail Johnson, Anoka, MN Secretary....................................................................................................................................... Arlene Restad, Eagan, MN Creative Activities Rules 1. ENTRIES. Open Monday, June 7. Entries close for all divisions Tuesday, Aug. 10, at 4:30 p.m. No exceptions. A. ONLINE REGISTRATION. All entries MUST be registered. Entries close on Tuesday, Aug. 10, at 4:30 p. m. No entries will be accepted after closing date. Errors or omissions must be registered within 10 days after fair closes. No entry fee required. 1. A confirmation will be sent to your email within 24 hours. Exhibitors must bring their registration confirmation during specified drop off dates and times for verification purposes only. A hard copy printed OR readily available to be viewed easily on a mobile device will be required at drop off. 2. Refer to the "How To Enter Exhibits" document for detailed information and entry procedures. Visit the Minnesota State Fair website to begin the registration process: competition.mnstatefair.org B. MAIL-IN REGISTRATION. Must be in our office (not postmarked) by Tuesday, Aug. 10, at 4:30 p.m. No entries will be accepted after closing date. All entries MUST be registered. Follow procedure below: 1. On an 8 1/2” x 11” sheet of paper. Must include 1) first name, last name, address and phone number; 2) list of class number(s) and description of entry for each exhibit. 2. Mail to: Competition Department - c/o: Creative Activities, Minnesota State Fair, 1265 Snelling Ave. N., St. Paul, MN 55108. -

North Cascades Sweaterscapes

North Cascades Sweaterscapes Climbers find some of the world's most challenging ascents in the rugged Picket Range of Washington state.. We hope you will enjoy the challenge of knitting this sweater as well! An Intar sia Landscape Sweater design by Lynne & Douglas Barr Copyright ©2009 Lynne & Doug las Barr e-mail: [email protected] www.sweaterscapes.c om Instructions Finished Sweater Measurements Begin neck shaping on row 140. Chest: 39 (42,45) inches We recommend using short-row wrapping for the neck opening. It eliminates the seam between sweater and Length: 24 (26,28) inches neck rib and produces a neck opening with the proper Equipment stretch. #4 and #6 needles (or size needed to obtain gauge) Illustrated instructions can be viewed at Row Counter www.sweaterscapes.com. Bobbins Sweater Back Materials Using size 4 needle and White yarn, cast on 6(8,10) Green Mountain Spinnery yarns, 4 ounces/250 yard stitches. Then cast on 92(98,104) sts with Indigo yarn. skeins Rib in K2, P2 pattern for 2 inches, twisting the yarns when changing colors as when knitting intarsia. 4(4,5) oz Champlain Blue 8 oz Indigo Change to size 6 needles and follow sweater chart for 6 oz Light Grey the back. 6 oz Natural Grey Knit stitches on chart: 4 oz White small 9-106 medium 5-110 large 1-114 1 oz Blue Spruce Knit rows on chart: 1 oz Ivy small 17-171 medium 7-175 large 1-179 1 oz Blueberry 1 oz Aquamarine Finishing Gauge Weave in the ends from the intarsia knitting. -

40Th FREE with Orders Over

By Appointment To H.R.H. The Duke Of Edinburgh Booksellers London Est. 1978 www.bibliophilebooks.com ISSN 1478-064X CATALOGUE NO. 366 OCT 2018 PAGE PAGE 18 The Night 18 * Before FREE with orders over £40 Christmas A 3-D Pop- BIBLIOPHILE Up Advent th Calendar 40 with ANNIVERSARY stickers PEN 1978-2018 Christmas 84496, £3.50 (*excluding P&P, Books pages 19-20 84760 £23.84 now £7 84872 £4.50 Page 17 84834 £14.99 now £6.50UK only) 84459 £7.99 now £5 84903 Set of 3 only £4 84138 £9.99 now £6.50 HISTORY Books Make Lovely Gifts… For Family & Friends (or Yourself!) Bibliophile has once again this year Let us help you find a book on any topic 84674 RUSSIA OF THE devised helpful categories to make useful you may want by phone and we’ll TSARS by Peter Waldron Including a wallet of facsimile suggestions for bargain-priced gift buying research our database of 3400 titles! documents, this chunky book in the Thames and Hudson series of this year. The gift sections are Stocking FREE RUBY ANNIVERSARY PEN WHEN YOU History Files is a beautifully illustrated miracle of concise Fillers under a fiver, Children’s gift ideas SPEND OVER £40 (automatically added to narration, starting with the (in Children’s), £5-£20 gift ideas, Luxury orders even online when you reach this). development of the first Russian state, Rus, in the 9th century. tomes £20-£250 and our Yuletide books Happy Reading, Unlike other European countries, Russia did not have to selection. -

T.G.S.W. Library Catalogue

T.G.S.W. LIBRARY CATALOGUE AUTHOR FIRST NAME TITLE YR PUBLISHED BY TYPE SIZE Telos Art Publishing, Reference Art Textiles of the World:-Japan 1997 Winchester, G.B. books The British Wool Marketing British Sheep Breeds,Their Wool and Spinning Board, Isleworth Middlesex, Its Uses books G.B. Jeanne's list of Natural Dye Materials 1975 North Fork Press Dyeing books Weaving Tapestry -- A Woven Narrative 2012 Black Dog Publishing books Yarn Samples A. Jay and Abrams Building Craft Equipment 1976 Praeger Publishers Carol W. April 2016 T.G.S.W. LIBRARY CATALOGUE A. Jay and Building Craft Equipment: An Praeger Publishers, New Abrams 1976 Carol W. Illustrated Manual York Craft books Weaving Traditions of Highland Craft and Folk Museum, Los Weaving Adelson Takami L. and B. 1979 Bolivia Angelos, USA. books Adrosko Rita J. Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing Dyeing books Smithsonian Institution Adrosko Rita J. Natural Dyes in the United States 1968 Press Dyeing books Albers Josef Interaction of Colour 1977 Yale University Press Colour design Wesleyan University Press, Albers Anni On Designing 1971 Colour and Middletown,CON. design Albers Anni On weaving 1965 Weslyan University Press Weaving books Interweave Press, Alderman Sharon Handweavers Notebook 1990 Weaving Loveland,CO books Alderman Sharon Mastering Weave Structures 2004 Interweave press Weaving books April 2016 T.G.S.W. LIBRARY CATALOGUE Alderman & Sharon & Handwoven, Tailormade Interweave Press Wartenberger Kathryn Ontario Agriculture and Alex J.F. Ontario Weeds Food Ministry, Publication Switzer G.M. 505 Dyeing books Interweave Press, Loveland, Alexander Kathryn Spinning Energized Yarns 2012 DVD and CO. Videos Allard Mary Rug Making 1963 Chilton Company Designer’s Guide to Japanese Colour and Allen 2000 Jeanne Patterns 2 Chronicle Books design Interweave Press, Loveland, Amos Alden Big book of Handspinning 2001 Spinning CO. -

By Author As of 102711

THSG Library By Author As of 102711 100 3M 2004 Respirator Selection Guide 3M 532 A131n New Zealand Guide to Handmade Felt Abbott, Tim 364 A152m Multiple Harness Patterns From the Early 1700's (The Snavely Patterns) Able, Isable I. 095.4 A228w Weaving Traditions of Highland Bolivia Adelson, Lauri, and Takami 311 A242a American Loom: Plans for Making a 19th Century Loom Adrosko, Rita J. 120 A242n Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing Adrosko, Rita J. 361 A242w Weavers Draft Book and Clothiers Assistant, The Adrosko, Rita J. 367.2 WSN James Koehler Workshop: Hatching and Color Gradation Techniques for Tapestry Aiken, Roxanne 400 A294f Fiberarts Book of Wearable Art, The Aimone, Katherine Duncan 304 A325o Ojo de Dios - Eye of God Albaum, Charlet 331 A329o On Weaving Albers, Anni 022 A333u An Unthymely Death and Other Garden Mysteries Albert, Susan Wittig 022 A333i Indigo Dyeing Albert, Susan Wittig 351 A361m Mastering Weave Structures Alderman, Sharon 374 A361h Handweaver's Notebook, A Alderman, Sharon, and Wertenberger 376 A361h Handwoven, Tailormade Alderman, Sharon, and Wertenberger 401 C319g Good Houskeeping Needlecraft Encyclopedia, The Alice Carroll 333 A425w Weavers Way: Navajo Profiles, The Allen, Dodie 335 A426w Weaving Contemporary Rag Rugs Allen, Heather 400 ALF Late Victorian Needlework for Victorian Houses American Life Foundation 010 Ref Glossary of Wool Fabric Terms American Wool Council 300 AWC Weaving: A Timeless Craft American Wool Council 200 A525a Alden Amos Big Book of Handspinning, The Amos, Alden 002 A545n Needlecrafters' Travel Companion 4th Edition 2007-2009 Anderson, Audrey , and Swales 020 A545c Creative Spinning Weaving and Dyeing Anderson, Beryl 432 A545c Crewel Embroidery Anderson, F. -

Top-Down Raglan Pullover Lesson.Pdf

About Top-Down Raglan Pullovers the underarm is complete and the raglan piece joined to be worked in the round. The top-down raglan design is of "sea ms" are decreased to the neckline. From Continue increasing every other row until comparatively recent origin in terms of the top-down, the sleeve/body stitches are the piece is long/large enough to meet at swea ter design. Raglan construction was increased to the underarms and then th e the underarms. The sleeves/front/back arc created as a supplement to or replacement sleeves, front and back stitches separated separated at this point. Some designers have of the saddle shoulder sweater. See Suzanne and wo rked to the edgings as three separate the knitter work the sleeves first so they are Bryan's article "Raglan Sleeved Sweaters tubes. worked down to the wrist and finished off. from the Bottom Up" on page 46 for more Others instruct the knitter to work the body discussion o n the history of this design. Construct ion first and then the sleeves. In that instance, The hallmark of the raglan is the diagonal A top-down raglan is essentially a seamless the body is worked as a tube to the desired shaping lines moving from the top of the rectangular yoke. Once the math for gauge length and finished. Regardless of which neckline, to the underarm. Thus, the sleeve is complete, cast o n placing markers at is done first, some additional stitches may top is integrated into the neckline. This the four points dividing the back/sleeve/ be cast on for the underarms to reach the design eliminates the problem of excess front/sleeve (see Swatch 1) . -

Sweater-101-Sampler-Copy.Pdf

Sweater 101 How to Plan Sweaters that Fit ... and Organize Your Knitting Life at the Same Time In print again, Sweater 101 is called “a Timeless Classic” Cheryl Brunette For Lena and Magdalena, my mother and grandmother, through whose hands a million miles of threads flowed. Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................... 13 Knitting in the mid- 20th Century . 13 Knitting Today . 13 Goals of Sweater 101 . 14 Tools that Enhance Sweater 101........................................ 15 Your Knitting Notebook .............................................. 16 2 Basic Sweater Styles . 17 Making Fabric • Tubes vs Flat Pieces.................................... 17 Drop Shoulder . 19 Set-In Sleeve . 20 The Raglan . 21 3 A Couple of Math Skills ............................... 22 Your Calculator Memory.............................................. 22 More-or-Less-Right Formula Explained................................. 24 More-or-Less-Right Formula in a Nutshell . 28 4 Finding Your Gauge . 29 What is Gauge? • The Gauge Swatch ................................... 29 Row Gauge . 32 The Gauge Record Sheet.............................................. 33 5 How to Size a Sweater to Get the Fit You Really Want . 35 Three Sources of Information . 35 Longer or Shorter . 37 The Non-Hourglass Figure . 38 6 How to Take Body Measurements...................... 40 7 How to Assign Pattern Measurements................ 42 8 Filling in a Picture Pattern . .44 Charting a Drop Shoulder Pattern ..................................... 46 A Drop Shoulder Charting Example & Tips ............................ 50 Knitting Shoulders Together.......................................... 51 Charting a Set-In Pattern............................................. 53 Charting a Set-In Sleeve Cap . 56 A Set-In Charting Example & Tips . 59 Charting a Raglan Pattern . 62 A Raglan Charting Example & Tips.................................... 65 9 Beyond the Basics . 68 Playing with the Neckline • Collars • Plackets . 68 The V-Neck . 70 The Square Shawl . -

WEBS Spring Retreat

What’s Included? Instructors We have some of the most Sumptuous swag bags that will be mailed talented instructors to attendees sharing their expertise Two full days of online classes, as well as this weekend! morning yoga Virtual trunk shows and Q&A sessions Lily Chin with our sponsors Patty Lyons An all-day lounge for you to join at your WEBS Spring Knitting Retreat leisure with events and games taking Gudrun Johnston April 29th - May 2nd, 2021 place each day Keith Leonard Our WEBS Knitting Retreat has An exclusive shopping coupon code just Josh Bennett gone virtual for May 2021! We for retreat attendees Laura Nelkin want you to have the fun of the Retreat from the safety of your living room or craft space, and we all hope you'll be excited to try this new adventure with us! Teacher Bios Lily Chin Gudrun Johnston Lily M. Chin is an internationally famous Patty Lyons Gudrun was born in Shetland in the 70’s while knitter and crocheter who has worked in the Patty Lyons (http://pattylyons.com/) is a nationally her mother, Patricia Johnston, was running the yarn industry for more than 30 years, as a recognized knitting teacher and technique expert successful knitwear design company, The designer, instructor, and author of 8 books on who is known for teaching the “why” not just the Shetland Trader. She has made a name for knitting and crochet. Lily teaches around the “how” in her pursuit of training the “mindful herself among a new generation of knitwear world and now has instructional DVDs out as knitter”. -

Downloading Or Purchasing Online At

Properties, Processing and Performance of Rare and Natural Fibres A review and interpretation of existing research results OCTOBER 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/150 Properties, Processing and Performance of Rare Natural Animal Fibres A review and interpretation of existing research results by B.A. McGregor October 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/150 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-002521 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-333-8 ISSN 1440-6845 Properties, Processing and Performance of Rare Natural Animal Fibres: A review and interpretation of existing research results Publication No. 11/150 Project No. PRJ-002521 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. -

Autumn Aspens Sweaterscapes

Autumn Aspens Sweaterscapes This sweater captures ththee brilliance and milemile----highhigh blue sky of ColoradoColorado.... An Intarsia Landscape Sweater design by Lynne & Douglas Barr Copyright ©2009 Lynne & Doug las Barr e-mail: [email protected] www.sweaterscapes.com Instructions Finished Sweater Measurements Begin neck shaping on row 128. We recommend using short-row wrapping for the neck Chest: 42 (45,48) inches opening. It eliminates the seam between sweater and Length: 25 (27,29) inches neck rib and produces a neck opening with the proper Equipment stretch. #6 and #8 needles (or size needed to obtain gauge) Illustrated instructions can be viewed at Row Counter www.sweaterscapes.com. Bobbins Sweater Back Materials Using Shaba Green yarn and size 8 needle, cast on Peace Fleece yarns, 4 ounces/200 yard skeins 82(90,94) stitches. Change to size 6 needles, and rib in K2, P2 pattern for 2 inches. Increase 2(0,2) stitches 14 oz Galooboy Blue after rib. 8 oz Shaba Green 5 oz Khrushchev Corn Change to size 8 needles and follow sweater chart for 4 oz Antarctica White the back (page 7). 2 oz Hand-dyed Gold Knit stitches on chart: 2 oz Negotiation Grey small 1-84 medium 1-90 large 1-96 2 oz Violet Vyehchyeerom Knit rows on chart: 2 oz Soyuz-Apollo Teal small 13-151 medium 7-155 large 1-159 1 oz Latvian Lavender 1 oz Baikal-Superior Green 1 oz Glastnost Gold Finishing Gauge Weave in the ends from the intarsia knitting. Stockinette Stitch: Using size 8 needles (or size needed Block sweater pieces before assembling and knitting to obtain gauge): 16 sts by 21 rows will make a 4 inch the neck rib. -

KITOW 1St Printing Index.Indd

Index is revised index applies only to the first printing of Knitting in the Old Way. If your book is from the first printing, the first word on page is Sweden. e affected pages are –, in which two electronic files swapped positions. e index supplied here corresponds to the printed page numbers. It complements a corresponding, revised version of page in the Contents. As an alternative, you may use the Contents and index as printed in the book by simply renumbering pages – as – (Chapter , Color Stranding; Norway) and pages – as – (Sweden). A intarsia, 199 Danish blouses, 132, 135, horizontal, 67 shepherd’s knitting, 295 234–38 with tubular-cord edging, 121 Abbey, Barbara, 51, 66 Austria and Germany, knitting of boat necklines vertical, 68 abbreviations Berchtesgaden Sweater, 276–77 basic directions, 128–29 elimination of when using Man’s Bavarian Vests, 271, 274 Icelanders, 174 C charts, 75 textured designs, 268–77 in Norwegian knitting, 146, for stitches, 57, 58, 72–73 traveling stitches, 224 154 cabled cast-on, 55 absorbency Tyrolean Jackets, 274, 275, 277 bobbles cables synthetic fibers, 34 Woman’s Bavarian Vest, 270 Aran fishing shirts, 260, 262, methods, 226–27 wool, 26 Woman’s Bavarian Waistcoat, 265 in patterns, 241, 255, 260, 261, acrylic yarns, 34, 35 268, 269 directions for, 228–29 275 Africa, origins of knitting, 23 B Tyrolean Jackets, 274 symbols for, 73, 226, 227 Alafoss Spinning Mill, 176 calculators, as knitting tool, 40, 81 backward knitting, see knitting in Bohus knitting allergies, to wool, 28 camel, 33 reverse Bohus