The Opening Night Simulcast of Filmfour on Channel 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

Desiring Postcolonial Britain: Genre Fiction Since the Satanic Verses

Desiring Postcolonial Britain: Genre Fiction sinceThe Satanic Verses Sarah Post, BA (Hons), MA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2012 This thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere ProQuest Number: 11003747 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003747 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 1 Acknowledgements The completion of this project would not have been possible without the academic, financial and emotional support of a great number of people. I would like to thank all those that offered advice on early drafts of my work at conferences and through discussions in the department. Special thanks go to the Contemporary Gothic reading group at Lancaster for engendering lively debate that fed into my understanding of what the Gothic can do today. Equally, I could not have finished the project without financial support, for which I am grateful to the Lancaster English Department for a fee waiver and to Dr. -

Al Pacino Receives Bfi Fellowship

AL PACINO RECEIVES BFI FELLOWSHIP LONDON – 22:30, Wednesday 24 September 2014: Leading lights from the worlds of film, theatre and television gathered at the Corinthia Hotel London this evening to see legendary actor and director, Al Pacino receive a BFI Fellowship – the highest accolade the UK’s lead organisation for film can award. One of the world’s most popular and iconic stars of stage and screen, Pacino receives a BFI Fellowship in recognition of his outstanding achievement in film. The presentation was made this evening during an exclusive dinner hosted by BFI Chair, Greg Dyke and BFI CEO, Amanda Nevill, sponsored by Corinthia Hotel London and supported by Moët & Chandon, the official champagne partner of the Al Pacino BFI Fellowship Award Dinner. Speaking during the presentation, Al Pacino said: “This is such a great honour... the BFI is a wonderful thing, how it keeps films alive… it’s an honour to be here and receive this. I’m overwhelmed – people I’ve adored have received this award. I appreciate this so much, thank you.” BFI Chair, Greg Dyke said: “A true icon, Al Pacino is one of the greatest actors the world has ever seen, and a visionary director of stage and screen. His extraordinary body of work has made him one of the most recognisable and best-loved stars of the big screen, whose films enthral and delight audiences across the globe. We are thrilled to honour such a legend of cinema, and we thank the Corinthia Hotel London and Moët & Chandon for supporting this very special occasion.” Alongside BFI Chair Greg Dyke and BFI CEO Amanda Nevill, the Corinthia’s magnificent Ballroom was packed with talent from the worlds of film, theatre and television for Al Pacino’s BFI Fellowship presentation. -

Barbie Bake-Off and Risk Or Role the Apprentice Model? Documentary Pokémon Go Shorts

FEBRUARY 2017 ISSUE 59 POST-TRUTH RESEARCHING THE PAST BARBIE BAKE-OFF AND RISK OR ROLE THE APPRENTICE MODEL? DOCUMENTARY POKÉMON GO SHORTS MM59_cover_4_feb.indd 1 06/02/2017 14:00 Contents 04 Making the Most of MediaMag MediaMagazine is published by the English and Media 06 What’s the Truth in a Centre, a non-profit making Post-fact World? organisation. The Centre Nick Lacey explores the role publishes a wide range of of misinformation in recent classroom materials and electoral campaigns, and runs courses for teachers. asks who is responsible for If you’re studying English 06 gate-keeping online news. at A Level, look out for emagazine, also published 10 NW and the Image by the Centre. System at Work in the World Andrew McCallum explores the complexities of image and identify in the BBC television 30 16 adaptation of Zadie Smith’s acclaimed novel, NW. 16 Operation Julie: Researching the Past Screenwriter Mike Hobbs describes the challenges of researching a script for a sensational crime story forty years after the event. 20 20 Bun Fight: How The BBC The English and Media Centre 18 Compton Terrace Lost Bake Off to Channel 4 London N1 2UN and Why it Matters Telephone: 020 7359 8080 Jonathan Nunns examines Fax: 020 7354 0133 why the acquisition of Bake Email for subscription enquiries: Off may be less than a bun [email protected] in the oven for Channel 4. 25 Mirror, Mirror, on the Editor: Jenny Grahame Wall… Mark Ramey introduces Copy-editing: some of the big questions we Andrew McCallum should be asking about the Subscriptions manager: nature of documentary film Bev St Hill 10 and its relationship to reality. -

Casting Announced for BBC One's the Pale Horse

Casting announced for BBC One’s The Pale Horse Date: 31.07.2019 Casting for the latest Agatha Christie drama, The Pale Horse has been announced by BBC One, Mammoth Screen and Agatha Christie Limited. Rufus Sewell (The Man In The High Castle, The Marvellous Mrs. Maisel, The Father), plays Mark Easterbrook and is joined by Kaya Scodelario (Crawl, Extremely Wicked and Shockingly Evil And Vile) playing Hermia, Bertie Carvel (Doctor Foster, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell) as Zachariah Osborne, Sean Pertwee (Gotham, Elementary) as Detective Inspector Lejeune, Henry Lloyd-Hughes (Killing Eve, Indian Summers) as David Ardingly, and Poppy Gilbert (Call The Midwife) as Thomasina Tuckerton, Madeleine Bowyer (Black Mirror, Britannia) as Jessie Davis and Ellen Robertson (Snowflake, Britney Soho) as Poppy. Sarah Woodward (Queens Of Mystery, Loving Miss Hatto), Georgina Campbell (His Dark Materials, Black Mirror) and Claire Skinner (Outnumbered, Vanity Fair) will also star. Completing the cast are Rita Tushingham (Vera, A Taste Of Honey) as Bella, Sheila Atim (Girl From The North Country, Bloodmoon) as Thryza Grey and Kathy Kiera Clarke (Derry Girls, Tartuffe) as Sybil Stamford who will play the trio of witches. The Pale Horse follows Mark Easterbrook as he tries to uncover the mystery of a list of names found in the shoe of a dead woman. His investigation leads him to the peculiar village of Much Deeping, and The Pale Horse, the home of a trio of rumoured witches. Word has it that the witches can do away with wealthy relatives by means of the dark arts, but as the bodies mount up, Mark is certain there has to be a rational explanation. -

Norwich Film Festival Is Accredited by Both the British Independent Film Awards and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts

NORWICH FILMFESTIVAL #NFF2019 6-17 NOVEMBER 2019 Supported by THANK YOU TO ALL OUR SUPPORTERS SPONSORS OF BEST SPONSORS OF BEST SPONSORS OF BEST DOCUMENTARY FILM EAST ANGLIAN FILM SHORT FILM THE TIMOTHY COLMAN TRUST NORWICH FILM FESTIVAL IS ACCREDITED BY BOTH THE BRITISH INDEPENDENT FILM AWARDS AND THE BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND TELEVISION ARTS BIFA BAFTA QUALIFYING FESTIVAL QUALIFYING FESTIVAL BRITISH SHORT FILM BRITISH SHORT FILM CONTENTS WELCOME NOTES 4 OUR TEAM 5 FESTIVAL MAP 6 SUMMARY OF EVENTS 8 LAUNCH NIGHT 12 DAY ONE 13 DAY TWO 14 DAY THREE 15 DAY FOUR 18 DAY FIVE 21 DAY SIX 22 DAY SEVEN 24 DAY EIGHT 26 DAY NINE 30 DAY TEN 35 OFFICIAL SELECTION 38 OUR JUDGES 40 NOMINATED FILMS 42 FESTIVAL TIMETABLE 46 norwichfilmfestival.co.uk 3 WE’RE BACK and we’re incredibly excited to bring you the ninth Norwich Film Festival! We’ve had a record number of submissions this year, and we’ve spent months carefully choosing our Official Selection to present to you this month. We have 111 great short films, as well as 10 brilliant feature films, and a huge selection of industry sessions and talks. We’re extremely grateful for the continued support of our sponsors, partners, and friends, and we wouldn’t be where we are today without your help. We’re also proud of the ongoing commitment from our team of volunteers and the staff of all the venues hosting us across the city. The festival is what it is because of them, but also because of you, our audience. -

Independent Television Producers in England

Negotiating Dependence: Independent Television Producers in England Karl Rawstrone A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Creative Industries, University of the West of England, Bristol November 2020 77,900 words. Abstract The thesis analyses the independent television production sector focusing on the role of the producer. At its centre are four in-depth case studies which investigate the practices and contexts of the independent television producer in four different production cultures. The sample consists of a small self-owned company, a medium- sized family-owned company, a broadcaster-owned company and an independent- corporate partnership. The thesis contextualises these case studies through a history of four critical conjunctures in which the concept of ‘independence’ was debated and shifted in meaning, allowing the term to be operationalised to different ends. It gives particular attention to the birth of Channel 4 in 1982 and the subsequent rapid growth of an independent ‘sector’. Throughout, the thesis explores the tensions between the political, economic and social aims of independent television production and how these impact on the role of the producer. The thesis employs an empirical methodology to investigate the independent television producer’s role. It uses qualitative data, principally original interviews with both employers and employees in the four companies, to provide a nuanced and detailed analysis of the complexities of the producer’s role. Rather than independence, the thesis uses network analysis to argue that a television producer’s role is characterised by sets of negotiated dependencies, through which professional agency is exercised and professional identity constructed and performed. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M. -

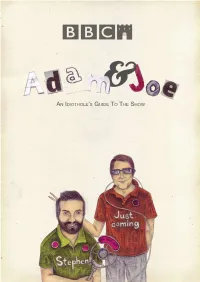

An Idiothole's Guide to the Show

AN ID I OTHOLE ’S GU I DE TO THE SHOW ABOUT THE SHOW AN INTRODUCT I ON The Adam and Joe Show is a BBC6 Music radio slot on Saturday morning that starts at an un-godly 9:00am and ends at a much more reasonable 12:00pm. To date I must confess I have only ever once dragged myself out of bed to listen to the show. It was hard, but worth it if only for the communal idea of us all being...um...awake at the same time. (Not sure if I could manage it again. My partner grumbled about my early morning homage the whole way through. “Adam & Joe! Stupid Adam and Joe! I’m going to call them and tell them they are ruining my life!“ said with no small level of venom.) The show is hosted by Adam Buxton, a comedian, actor and music buff & Joseph Murray Cornish a writer, occasional actor and movie fanatic. Once upon a time they used to be on TV hosting their home-made pop-culture laden show on Channel 4 which for some reason Channel 4 ended after four seasons (what fools!). Luckily all the shows have been archived online and are free to watch at leisure. (Go to the Useful Links page for the web link. The show features music broken up by listener interactive elements and a lot of chit-chat bewteen the duo (who have known each other since they were in school) that you can giggle at while on the way to work, at work or even as suggested by A&J, on the loo. -

The Old Collyerians' Association Spring 2016

TheThe OldOld Collyerians’Collyerians’ AssociationAssociation Spring 2016 President’s welcome words itting in the waiting room, on my Alongside I saw a new addition to the bi-annual visit to the dentist, I literature: a shelf full books which had Susually like to browse through the been left by fellow patients, and which magazines, which are usually the up could be purchased by giving a voluntary market variety, e.g. Tatler, Country Life, donation to the local hospice. Naturally The Lady etc. But on my most recent there was quite an assortment of visit, these were no longer available, so I reading material but I selected on a book was left with outdated copies of Hello written by a 91 year old in 2013 on the and OK magazines, purported to many social and economic changes represent the trials and tribulations of throughout his lifetime. what is euphemistically know as the "A The book, with the fascinating title of list". Harry’s Last Stand, was described by the However, after a short while I quickly publisher as "a lyrical, searing modern came to the conclusion that most invective that shows what the past can photographs and articles covered birds, teach us, how the future is ours for the brides, babies and BAFTAs, not to taking". Harry, or to give him his full mention the Beckhams, so the term ‘B name Harry Leslie Smith, was born into list’ would seem far more appropriate. poverty in Barnsley, Yorkshire, his early Contact us President: Eric Austin Vice-President: Dave Picknell Secretary: Andrew Campbell Assistant Secretary/Recorder: Derek Sturt * Treasurer: Stewart Mackman Membership Secretary: Mark Collins, 4 Stallett Way, Tilney St Lawrence, Kings Lynn, Norfolk PE34 4HT Newsletter: Bill Thomson, The Haven, 18 Fern Road, Storrington, W. -

Rebecca Frayn Writer-Director

Rebecca Frayn Writer-Director Rebecca Frayn was trained by the BBC as a film editor, before going on to develop a successful career as a freelance director for signature documentaries, a screenwriter and commercials director. She is represented for commercials by Arden Sutherland Dodd. Agents Natasha Galloway Associate Agent Talia Tobias [email protected] + 44 (0) 20 3214 0860 Credits Drama Production Company Notes THE LADY Left Bank Screenplay. Luc Besson directing. Starring 2010 Films/Europacorp Michelle Yeoh and David Thewlis. WHOSE BABY? Granada/ ITV 90′ single film, starring Sophie Okenodo and 2004 Andrew Lincoln. Tx November 2004 SINGLE Tiger Aspect/ ITV 3 episodes of 3 x 60′. Starring Michelle Collins. 2002 Producer: Amanda Davis. Writer: Peter Bowker. Exec Producer: Jane Fallon. TX: from 25th October 03, 9.30pm. ROCKING THE LWT 1 hour pilot for 6 part series. CRADLE Producer: Sally Head 1997 KAVANAGH QC IV: Carlton 90′ script. Producer: Chris Kelly 'ONLY THE LONELY' 1997 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes SCREEN ONE ONE - Middlemarch Films / Based on the true story of Sara Thornton. KILLING ME SOFTLY BBC 2 Broadcast 7/7/96. 1995 Produced by Belinda Allen & Elinor Day. Directed by Stephen Whittaker. Starring Maggie O’Neill & Peter Howitt. BEGGAR MAN, THIEF Middlemarch Films / Original screenplay developed for Film on Four. 1994 Channel 4 Producer: Belinda Allen HE PLAY/SHE PLAY - Middlemarch Films / Contemporary version of OTHELLO. Broadcast THE LAST LAUGH Channel 4 28/4/93.