Balboa Park Station Area Plan Archeological Context (Final)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argonaut #2 2019 Cover.Indd 1 1/23/20 1:18 PM the Argonaut Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society Publisher and Editor-In-Chief Charles A

1/23/20 1:18 PM Winter 2020 Winter Volume 30 No. 2 Volume JOURNAL OF THE SAN FRANCISCO HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOL. 30 NO. 2 Argonaut #2_2019_cover.indd 1 THE ARGONAUT Journal of the San Francisco Historical Society PUBLISHER AND EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Charles A. Fracchia EDITOR Lana Costantini PHOTO AND COPY EDITOR Lorri Ungaretti GRapHIC DESIGNER Romney Lange PUBLIcatIONS COMMIttEE Hudson Bell Lee Bruno Lana Costantini Charles Fracchia John Freeman Chris O’Sullivan David Parry Ken Sproul Lorri Ungaretti BOARD OF DIREctORS John Briscoe, President Tom Owens, 1st Vice President Mike Fitzgerald, 2nd Vice President Kevin Pursglove, Secretary Jack Lapidos,Treasurer Rodger Birt Edith L. Piness, Ph.D. Mary Duffy Darlene Plumtree Nolte Noah Griffin Chris O’Sullivan Richard S. E. Johns David Parry Brent Johnson Christopher Patz Robyn Lipsky Ken Sproul Bruce M. Lubarsky Paul J. Su James Marchetti John Tregenza Talbot Moore Diana Whitehead Charles A. Fracchia, Founder & President Emeritus of SFHS EXECUTIVE DIREctOR Lana Costantini The Argonaut is published by the San Francisco Historical Society, P.O. Box 420470, San Francisco, CA 94142-0470. Changes of address should be sent to the above address. Or, for more information call us at 415.537.1105. TABLE OF CONTENTS A SECOND TUNNEL FOR THE SUNSET by Vincent Ring .....................................................................................................................................6 THE LAST BASTION OF SAN FRANCISCO’S CALIFORNIOS: The Mission Dolores Settlement, 1834–1848 by Hudson Bell .....................................................................................................................................22 A TENDERLOIN DISTRIct HISTORY The Pioneers of St. Ann’s Valley: 1847–1860 by Peter M. Field ..................................................................................................................................42 Cover photo: On October 21, 1928, the Sunset Tunnel opened for the first time. -

H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space

IV. Environmental Setting and Impacts H. Parks, Recreation and Open Space Environmental Setting The San Francisco Recreation and Park Department maintains more than 200 parks, playgrounds, and open spaces throughout the City. The City’s park system also includes 15 recreation centers, nine swimming pools, five golf courses as well as tennis courts, ball diamonds, athletic fields and basketball courts. The Recreation and Park Department manages the Marina Yacht Harbor, Candlestick (Monster) Park, the San Francisco Zoo, and the Lake Merced Complex. In total, the Department currently owns and manages roughly 3,380 acres of parkland and open space. Together with other city agencies and state and federal open space properties within the city, about 6,360 acres of recreational resources (a variety of parks, walkways, landscaped areas, recreational facilities, playing fields and unmaintained open areas) serve San Francisco.172 San Franciscans also benefit from the Bay Area regional open spaces system. Regional resources include public open spaces managed by the East Bay Regional Park District in Alameda and Contra Costa counties; the National Park Service in Marin, San Francisco and San Mateo counties as well as state park and recreation areas throughout. In addition, thousands of acres of watershed and agricultural lands are preserved as open spaces by water and utility districts or in private ownership. The Bay Trail is a planned recreational corridor that, when complete, will encircle San Francisco and San Pablo Bays with a continuous 400-mile network of bicycling and hiking trails. It will connect the shoreline of all nine Bay Area counties, link 47 cities, and cross the major toll bridges in the region. -

San Mateo Countywide Transportation Plan 2040 SMCTP 2040

February 9, 2017 San Mateo Countywide Transportation Plan 2040 SMCTP 2040 Prepared by the City/County Association of Governments of San Mateo County Adopted February 9, 2017 City/County Association of Governments of San Mateo County Acknowledgements A special thanks to the following individuals for their vital participation throughout the planning and implementing process for the San Mateo Countywide Transportation Plan 2040. C/CAG Board of Directors Elizabeth Lewis, Atherton Doug Kim, Belmont Cliff Lentz, Brisbane Ricardo Ortiz, Burlingame Diana Colvin, Colma Judith Christensen, Daly City Lisa Gauthier, East Palo Alto Herb Perez, Foster City Debbie Ruddock, Half Moon Bay Larry May, Hillsborough Catherine Carlton, Menlo Park Gina Papan, Millbrae Mike O’Neill, Pacifica Maryann Moise Derwin, Portola Valley - Vice Chair Alicia Aguirre, Redwood City - Chair Irene O’Connell, San Bruno Mark Olbert, San Carlos Diane Papan, City of San Mateo David Canepa, San Mateo County Karyl Matsumoto, South San Francisco and San Mateo County Transportation Authority Deborah Gordon, Woodside C/CAG Congestion Management and Environmental Quality / Policy Advisory Committee Alicia Aguirre, Metropolitan Transportation Commission Emily Beach, Burlingame Charles Stone, Belmont Elizabeth Lewis, Atherton Irene O’Connell, San Bruno Linda Koelling, Business Community John Keener, Pacifica Lennie Roberts, Environmental Community Mike O’Neill, Pacifica -Vice Chair Adina Levin, Agencies with Transportation Interests Richard Garbarino, South San Francisco -Chair Rick Bonilla, -

AQ Conformity Amended PBA 2040 Supplemental Report Mar.2018

TRANSPORTATION-AIR QUALITY CONFORMITY ANALYSIS FINAL SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT Metropolitan Transportation Commission Association of Bay Area Governments MARCH 2018 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Jake Mackenzie, Chair Dorene M. Giacopini Julie Pierce Sonoma County and Cities U.S. Department of Transportation Association of Bay Area Governments Scott Haggerty, Vice Chair Federal D. Glover Alameda County Contra Costa County Bijan Sartipi California State Alicia C. Aguirre Anne W. Halsted Transportation Agency Cities of San Mateo County San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission Libby Schaaf Tom Azumbrado Oakland Mayor’s Appointee U.S. Department of Housing Nick Josefowitz and Urban Development San Francisco Mayor’s Appointee Warren Slocum San Mateo County Jeannie Bruins Jane Kim Cities of Santa Clara County City and County of San Francisco James P. Spering Solano County and Cities Damon Connolly Sam Liccardo Marin County and Cities San Jose Mayor’s Appointee Amy R. Worth Cities of Contra Costa County Dave Cortese Alfredo Pedroza Santa Clara County Napa County and Cities Carol Dutra-Vernaci Cities of Alameda County Association of Bay Area Governments Supervisor David Rabbit Supervisor David Cortese Councilmember Pradeep Gupta ABAG President Santa Clara City of South San Francisco / County of Sonoma San Mateo Supervisor Erin Hannigan Mayor Greg Scharff Solano Mayor Liz Gibbons ABAG Vice President City of Campbell / Santa Clara City of Palo Alto Representatives From Mayor Len Augustine Cities in Each County City of Vacaville -

Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report

Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report May 7, 2015 Prepared jointly by CDM Smith and the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District, Office of Civil Rights 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Section 1: Introduction 6 Section 2: Project Description 7 Section 3: Methodology 14 Section 4: Service Analysis Findings 23 Section 5: Fare Analysis Findings 27 Appendix A: 2011 Warm Springs Survey 33 Appendix B: Proposed Service Options Description 36 Public Participation Report 4 1 2 Warm Springs Extension Title VI Equity Analysis and Public Participation Report Executive Summary In June 2011, staff completed a Title VI Analysis for the Warm Springs Extension Project (Project). Per the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Title VI Circular (Circular) 4702.1B, Title VI Requirements and Guidelines for Federal Transit Administration Recipients (October 1, 2012), the District is required to conduct a Title VI Service and Fare Equity Analysis (Title VI Equity Analysis) for the Project's proposed service and fare plan six months prior to revenue service. Accordingly, staff completed an updated Title VI Equity Analysis for the Project’s service and fare plan, which evaluates whether the Project’s proposed service and fare will have a disparate impact on minority populations or a disproportionate burden on low-income populations based on the District’s Disparate Impact and Disproportionate Burden Policy (DI/DB Policy) adopted by the Board on July 11, 2013 and FTA approved Title VI service and fare methodologies. Discussion: The Warm Springs Extension will add 5.4-miles of new track from the existing Fremont Station south to a new station in the Warm Springs district of the City of Fremont, extending BART’s service in southern Alameda County. -

2015 Station Profiles

2015 BART Station Profile Study Station Profiles – Non-Home Origins STATION PROFILES – NON-HOME ORIGINS This section contains a summary sheet for selected BART stations, based on data from customers who travel to the station from non-home origins, like work, school, etc. The selected stations listed below have a sample size of at least 200 non-home origin trips: • 12th St. / Oakland City Center • Glen Park • 16th St. Mission • Hayward • 19th St. / Oakland • Lake Merritt • 24th St. Mission • MacArthur • Ashby • Millbrae • Balboa Park • Montgomery St. • Civic Center / UN Plaza • North Berkeley • Coliseum • Oakland International Airport (OAK) • Concord • Powell St. • Daly City • Rockridge • Downtown Berkeley • San Bruno • Dublin / Pleasanton • San Francisco International Airport (SFO) • Embarcadero • San Leandro • Fremont • Walnut Creek • Fruitvale • West Dublin / Pleasanton Maps for these stations are contained in separate PDF files at www.bart.gov/stationprofile. The maps depict non-home origin points of customers who use each station, and the points are color coded by mode of access. The points are weighted to reflect average weekday ridership at the station. For example, an origin point with a weight of seven will appear on the map as seven points, scattered around the actual point of origin. Note that the number of trips may appear underrepresented in cases where multiple trips originate at the same location. The following summary sheets contain basic information about each station’s weekday non-home origin trips, such as: • absolute number of entries and estimated non-home origin entries • access mode share • trip origin types • customer demographics. Additionally, the total number of car and bicycle parking spaces at each station are included for context. -

Transit Information Millbrae Station Millbrae

BASE Schedules & Fares Horario y precios del tránsito 時刻表與車費 Transit For more detailed information about BART Information service, please see the BART schedule, BART system map, and other BART information displays in this station. Millbrae San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Schedule Information e ective June, 2020 Early Bird Express bus service SamTrans provides bus service Schedule Information e ective August 16, 2020 throughout San Mateo County Transit (BART) rail service connects runs weekdays from 4:00 a.m. to 5:00 Check before you go: up-to-date schedules are available at samtrans.com. The SamTrans Mobile app also provides Check before you go: up-to-date schedules are available on www.bart.gov and the o cial and to Peninsula BART stations, Station the San Francisco Peninsula with a.m., before BART opens. Early Bird both real time information and schedules. Or, call 1-800-660-4287 for schedule information. A quick reference guide BART app. Overhead real time displays can be found on station platforms. A reference guide Caltrain stations, and downtown Oakland, Berkeley, Berryessa, Express bus service connects East Bay, to service hours is shown. Walnut Creek, Dublin/Pleasanton, and to transfer information for trains without direct service is shown. San Francisco, and Peninsula BART stations. San Francisco. For more information visit other cities in the East Bay, as well as San For more information, call 510-465-2278. www.samtrans.com, or call 1-800-660-4287 Departing from Millbrae BART Francisco International Airport (SFO) and or 650-508-6448 (TTY). Mon-Fri Sat Sun/Holidays Route 38 Millbrae Oakland International Airport (OAK). -

Netsci Transportation Information

The Transportation Information for NetSci 2014 1. SFO to Clark Kerr and Claremont Airport Shuttles from San Francisco International Airport to Clark Kerr and Claremont Hotel Airport shuttles provide door-to-door service. The price is $34 for one person and 15 for additional person. The total occupancy of the shuttle is for 7 people. Reservations are recommended. Bay Porter Express 1-877-467-1800 (Bay Area toll free) • 1-415-467-1800 (outside Bay Area) East Bay Transportation 1-877-526-0304, 1-510-526-0304 Airport Commuter 1-888-876-1777 Taxi Taxi fare to Berkeley will be approximately $78 from the San Francisco airport. http://www.veteranstaxicab.com/ BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) BART is the Bay Area's subway system. The campus is closest to the Downtown Berkeley station on the Richmond line and to the Rockridge station on the Pittsburg/Bay Point line. There is no direct connection to downtown Berkeley from San Francisco on Sundays and evenings. At those times, take the Pittsburg/Bay Point train and transfer to a Richmond train at the 12th Street (Oakland) station (traveling to San Francisco at those times, transfer at MacArthur station). Monday - Friday, 4 a.m. to midnight* Saturday, 6:00 a.m. to midnight* Sunday, 8:00 a.m. to midnight* *In many cases, BART service extends past midnight. Individual station closing times are coordinated with the schedule for the last train, beginning at around midnight. BART trains typically run every 15 minutes on weekdays and every 20 minutes on evenings, weekends and holidays. For exact times, check the following website. -

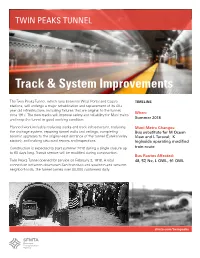

Track & System Improvements

TWIN PEAKS TUNNEL Track & System Improvements The Twin Peaks Tunnel, which runs between West Portal and Castro TIMELINE stations, will undergo a major rehabilitation and replacement of its 40+ year old infrastructure, including fixtures that are original to the tunnel, When: circa 1917. The new tracks will improve safety and reliability for Muni trains and keep the tunnel in good working condition. Summer 2018 Planned work includes replacing tracks and track infrastructure, replacing Muni Metro Changes: the drainage system, repairing tunnel walls and ceilings, completing Bus substitute for M Ocean seismic upgrades to the original east entrance of the tunnel (Eureka Valley View and L Taraval; K station), and making structural repairs and inspections. Ingleside operating modified Construction is expected to start summer 2018 during a single closure up train route to 60 days long. Transit service will be modified during construction. Bus Routes Affected: Twin Peaks Tunnel opened for service on February 3, 1918. A vital 48, 57, Nx, L OWL, 91 OWL connection between downtown San Francisco and southern and western neighborhoods, the tunnel carries over 80,000 customers daily. sfmta.com/twinpeaks Taraval Bus Ingleside • SF Zoo via Dewey/Woodside to Castro • Trains will operate between Sloat/St. Francis Station (will not stop at Church or West and Balboa Park Station and continue as Portal Stations) J Church to Embarcadero • Transfer at Sloat/St. Francis for M Ocean Ocean View Bus View or Forest Hill Shuttle buses • Balboa Park via West Portal/Vicente to • Transfer to BART for faster trips Church Station (will not stop at Forest Hill downtown or Castro Stations) To downtown Taraval & WawonaDewey & Woodside Church Castro 48 Taraval & MUNI METRO 14th Ave SF Zoo • J, N, T, and S trains running increased service. -

Muni Metro Guide 1986

METRO GUIDE INTRODUCTION Welcome to Muni Metro! This brochure introduces you to Muni's light rail system, and offers a full descrip tion of its features. Five lines operate in the Muni Metro. Cars of the J, K, L, M and N lines run in the Market Street subway downtown, and branch off to serve dif ferent neighborhoods of the city. Tunnel portals are located at Duboce Avenue and Church Street and at West Portal. The light rail vehi cles feature high/low steps at center doors. In the subway, these steps remain flush with the car floor and station platforms. For street operation, the steps lower for easy access to the pavement. SUBWAY STATIONS MEZZANINE Muni Metro has nine subway stations: Embarcadero, The mezzanine is the Montgomery, Powell, Civic Center, Van Ness, Church, level immediately below Castro, Forest Hill, and West Portal. the street, where you pay your fare and enter STATION ENTRANCES the Metro system. At Embarcadero, Mont Orange Muni or BART/ gomery, Powell, and Muni signposts mark Civic Center Stations, subway entrances on Muni Metro shares the the street. Near the top mezzanine with BART, of the stairs, brown the Bay Area Rapid Transit system. BART and Muni signs list the different maintain separate station agent booths and faregates. Metro lines which stop Muni booths are marked with orange and BART with below. blue. Change machines may be used by all passen gers. Ticket machines issue BART tickets only. Though BART and Muni share the mezzanine level, they do not share the same platforms andrai/lines. Be sure to choose the right faregates. -

Mission District

CITY WITHIN A CITY: HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT FOR SAN FRANCISCO’S MISSION DISTRICT November 2007 Prepared by: City and County of San Francisco Planning Department ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Mayor Gavin Newsom Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board Lily Chan Robert W. Cherny, Vice President Courtney Damkroger Ina Dearman Karl Hasz M. Bridget Maley, President Alan Martinez Johanna Street Planning Department Dean Macris, Director of Planning Neil Hart, Chief of Neighborhood Planning Mark Luellen, Preservation Coordinator Matt Weintraub, Citywide Survey Project Manager (Author) Thanks also to: N. Moses Corrette, Rachel Force, and Beth Skrondal of the Historic Resources Survey Team Survey Advisory Committee Charles Edwin Chase San Francisco Architectural Heritage (former Executive Director), Historic Preservation Fund Committee Courtney Damkroger Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board Neil Hart Planning Department Tim Kelley Kelley & VerPlank Historical Resources Consulting M. Bridget Maley Architectural Resources Group, Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board Mark Ryser San Francisco Beautiful Marie Nelson California Office of Historic Preservation Christopher VerPlank Kelley & VerPlank Historical Resources Consulting CITY WITHIN A CITY: HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT FOR SAN FRANCISCO’S MISSION DISTRICT The activity which is the subject of this Historic Context Statement has been financed in part with Federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, through the California Office of Historic Preservation. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the California Office of Historic Preservation. Regulations of the U.S. -

SRTP Cover V2

Solano Transportation Authority Short Range Transit Plan Fairfield and Suisun Transit (FAST) August 20, 2013 Solano Transportation Authority Short Range Transit Plan Fairfield and Suisun Transit (FAST) Page intentionally left blank August 20, 2013 | Arup North America Ltd Solano Transportation Authority Short Range Transit Plan Fairfield and Suisun Transit (FAST) Fairfield and Suisun Transit Short Range Transit Plan FINAL REPORT August 2013 Prepared for Solano Transportation Authority One Harbor Center, Suite 130 Suisun City, CA 94585 Fairfield and Suisun Transit 2000 Cadenasso Drive Fairfield, CA CA 94533 Prepared by Arup 560 Mission Street, Suite 700 San Francisco, CA 94105 August 30, 2013 | Arup North America Ltd Solano Transportation Authority Short Range Transit Plan Fairfield and Suisun Transit (FAST) Page intentionally left blank August 20, 2013 | Arup North America Ltd Solano Transportation Authority Short Range Transit Plan Fairfield and Suisun Transit (FAST) Fairfield and Suisun Transit (FAST) Short Range Transit Plan FY2012-13 to FY2022-23 Date Approved by Governing Board: August 20, 2013 Date Approved by STA Board: September 11, 2013 Federal transportation statutes require that the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC), in partnership with state and local agencies, develop and periodically update a long-range Regional Transportation Plan (RTP), and a Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) which implements the RTP by programming federal funds to transportation projects contained in the RTP. In order to effectively execute these planning and programming responsibilities, MTC requires that each transit operator in its region which receives federal funding through the TIP, prepare, adopt, and submit to MTC a Short Range Transit Plan (SRTP). The Board adopted resolution follows this page.