Diplomacy and Life on Georgia's Boundary Line Caecilia J. Van Peski 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Akhalgori Deadlock

Contributor to the publication: Giorgi Kanashvili Responsible for the publication: Ucha Nanuashvili English text editor: Vikram Kona Copyrights: Democracy Research Institute (DRI) This report is developed by the Democracy Research Institute (DRI), within the project Supporting Human Rights Protection at Front Line, with the financial support of the European Endowment for Democracy (EED). The project aims at protecting human rights in conflict- affected territories which, among others, implies monitoring of the situation in terms of human rights protection to fill information lacunae. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the position of the EED. Tbilisi 2021 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 4 THE CONTEXT: GEORGIAN-OSSETIAN RELATIONS SINCE 2008 ....................................... 4 THE SITUATION OF THE POPULATION OF AKHALGORI BEFORE THE CHORCHANA- TSNELISI CRISIS ............................................................................................................................... 6 THE CHORCHANA-TSNELISI CRISIS AND CREEPING ETHNIC CLEANSING IN AKHALGORI ........................................................................................................................................ 8 THE FUTURE OF THE POPULATION OF AKHALGORI AND THE POLICY TO BE PURSUED BY GEORGIAN AUTHORITIES ................................................................................ 10 03 INTRODUCTION -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Instructions

MY DETAILS My Name: Jong B. Mobile No.: 0917-5877-393 Movie Library Count: 8,600 Titles / Movies Total Capacity : 36 TB Updated as of: December 30, 2014 Email Add.: jongb61yahoo.com Website: www.jongb11.weebly.com Sulit Acct.: www.jongb11.olx.ph Location Add.: Bago Bantay, QC. (Near SM North, LRT Roosevelt/Munoz Station & Congressional Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table Drive Capacity Loadable Space Est. No. of Movies/Titles 320 Gig 298 Gig 35+ Movies 500 Gig 462 Gig 70+ Movies 1 TB 931 Gig 120+ Movies 1.5 TB 1,396 Gig 210+ Movies 2 TB 1,860 Gig 300+ Movies 3 TB 2,740 Gig 410+ Movies 4 TB 3,640 Gig 510+ Movies Note: 1. 1st Come 1st Serve Policy 2. Number of Movies/Titles may vary depends on your selections 3. SD = Standard definition Instructions: 1. Please observe the Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table above 2. Mark your preferred titles with letter "X" only on the first column 3. Please do not make any modification on the list. 3. If you're done with your selections please email to [email protected] together with the confirmaton of your order. 4. Pls. refer to my location map under Contact Us of my website YOUR MOVIE SELECTIONS SUMMARY Categories No. of titles/items Total File Size Selected (In Gig.) Movies (2013 & Older) 0 0 2014 0 0 3D 0 0 Animations 0 0 Cartoon 0 0 TV Series 0 0 Korean Drama 0 0 Documentaries 0 0 Concerts 0 0 Entertainment 0 0 Music Video 0 0 HD Music 0 0 Sports 0 0 Adult 0 0 Tagalog 0 0 Must not be over than OVERALL TOTAL 0 0 the Loadable Space Other details: 1. -

Russia's Kosovo: a Critical Geopolitics of the August 2008 War Over South

Toal.fm Page 670 Monday, December 22, 2008 10:20 AM Russia’s Kosovo: A Critical Geopolitics of the August 2008 War over South Ossetia Gearóid Ó Tuathail (Gerard Toal)1 Abstract: A noted political geographer presents an analysis of the August 2008 South Ossetian war. He analyzes the conflict from a critical geopolitical perspective sensitive to the importance of localized context and agency in world affairs and to the limitations of state- centric logics in capturing the connectivities, flows, and attachments that transcend state bor- ders and characterize specific locations. The paper traces the historical antecedents to the August 2008 conflict and identifies major factors that led to it, including legacies of past vio- lence, the Georgian president’s aggressive style of leadership, and renewed Russian “great power” aspirations under Putin. The Kosovo case created normative precedents available for opportunistic localization. The author then focuses on the events of August 2008 and the competing storylines promoted by the Georgian and Russian governments. Journal of Eco- nomic Literature, Classification Numbers: H10, I31, O18, P30. 7 figures, 2 tables, 137 refer- ences. Key words: South Ossetia, Georgia, Russia, North Ossetia, Abkhazia, genocide, ethnic cleansing, Kosovo, Tskhinvali, Saakashvili, Putin, Medvedev, Vladikavkaz, oil and gas pipe- lines, refugees, internally displaced persons, Kosovo precedent. he brief war between Georgian government forces and those of the Russian Federation Tin the second week of August 2008 was the largest outbreak of fighting in Europe since the Kosovo war in 1999. Hundreds died in the shelling and fighting, which left close to 200,000 people displaced from their homes (UNHCR, 2008b). -

Film Criticism

ALEXANDER FEDOROV FILM CRITICISM FEDOROV, A. FILM CRITICISM. МOSCOW: ICO “INFORMATION FOR ALL”. 2015. 382 P. COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY ALEXANDER FEDOROV [email protected] ALL RIGHT RESERVED. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 2 1 FEDOROV, ALEXANDER. 1954-. FILM CRITICISM / ALEXANDER FEDOROV. P. CM. INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES. 1. FILM CRITICISM. 2. FILM STUDIES. 3. MEDIA LITERACY. 4. MEDIA EDUCATION. 5. MEDIA STUDIES. 6. FILM EDUCATION. 7. STUDENTS. 8. CINEMA. 9. FILM. 10. MASS MEDIA. 11. STUDY AND TEACHING. 2 Contents The Mystery of Russian Cinema ………………………………..…... ..6 Phenomenon of Russian Film-Hits ………………………………….. 10 Russian Screen Distribution …………………………………..………..12 Video-pirates from Russia ……………………………………..…….. 15 Film Criticism and Press in Russia …………………………………… 17 Russian Cinematography and the Screen Violence ………………....….21 The Gloom of Russian Fantastic Movie-Land …………….………..….27 Sex-Cinema: Made in Russia …………………………………… ..….. 29 America, America… ……………………………………………….… .31 French Motives and Russian Melodies ………………………….…… .33 Fistful of Russian Movies ……………………………………….…… .41 Nikita Mikhalkov before XXI Century ………………………….…… 78 Karen Shakhnazarov: a Fortune's Favorite? ……………………….… 86 Pyotr Todorovsky: Dramatic Romance ……………………….……. 92 Oleg Kovalov, Former Film Critic .........................................................99 How to Shoot the “True” Film about Russia …………………………102 Locarno Film Fest: The View of a Film Educator ……………………103 The Analysis of Detective Genre at Film Education in Students’ Audience ……………………………………………… ……….…..106 Hermeneutical -

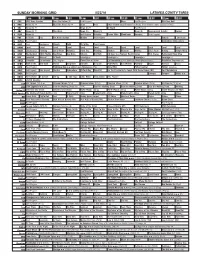

Sunday Morning Grid 5/22/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/22/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid 2016 French Open Tennis First Round. From Roland Garros Stadium in Paris. 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Supervisorial Debate Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program FabLab I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Somewhere Slow (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley Rick Steves Retirement Road Map 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

Georgian-South Ossetian Conflict: Researching Peace

Georgian-South Ossetian Conflict: Researching Peace Collection of South Ossetian Papers 2011 The preparation and publication of this work was made possible thanks to support from a variety of organizations and funds, including the Peacebuilding fund at George Mason University. Assistance with translation was provided by: Phil Gamaghelyan, Manana Gnolidze-Swanson, Olga Guschina, Dina Konysheva, and Nina Selwan. Project Coordinator: Kosta Dzugaev Editor: Susan Allen Nan Design: Artem Melik-Nubarov Copies printed: 250 © School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution, George Mason University; Center for Information Technology: Intellectual Resources. C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION Susan Allen Nan ... .. 4 FOREWORD TO THE SOUTH OSSETIAN COLLECTION Kosta Dzugaev ... 5 ECONOMIC REHABILITATION OF SOUTH OSSETIA: CURRENT PROBLEMS AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Batradz Kharebov ... 6 SOME ASPECTS OF SOLVING THE PROBLEMS OF REFUGEES AND INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS IN LIGHT OF GEORGIAN-OSSETIAN RELATIONS Merab Chigoev .... 33 LENINGOR REGION: ITS POLITICAL PECULIARITY, DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS, ECONOMY, AND BOUNDARY PROBLEMS Maria Kotaeva 52 INTRODUCTION The two sets of papers presented here were once simply an idea that seemed perhaps crazy. Without an introduction, the reader may find this volume schizophrenic. Holding the book in one direction, the reader will find three articles by Georgian researchers. Holding the book in another direction, the reader will find three articles by South Ossetian researchers. To read the other perspective, the reader must -

CHAPTER I Historicizing 5 Days of War the Phrase the Historicity Of

CHAPTER I Historicizing 5 Days of War The phrase the historicity of text and textuality of history has been popular among new historicists ever since the 1960s. They examine the dialectical relationship between history and literature. They interpret a literary text as a product and a producer of history. History cannot be divorced from textuality. Neither the text can be divorced from historicity, nor the text from contexts. Louis A. Montrose, a new historicist, in "Introduction: Professing the Renaissance: The poetics and Politics of Culture" underscores a reciprocal relationship between historicity and literature. While examining the dynamic dialogue between literature and history he appears with a phrase, "the historicity of texts and textuality of history". He further clarifies, "By the historicity of texts, I mean to suggest the cultural specificity, the social embedment, of all modes of writing" (20). Montrose suggests that history itself is a text and a literary text is bound up in its historical context. History is not something absolute and unchanging. It is a dynamic process of making, breaking and remaking of a text and its meanings. There is no one true version of history, just as there is no one true interpretation of the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. When historicists write history, they do not just re-state facts and figures but interpret these data. Historians compose history in the same way an author composes a literary text. Hence, literature is historically determined: 1 By the textuality of history, I mean to suggest, firstly, -

6 North and South Ossetia: Old Conflicts and New Fears

6 North and South Ossetia: Old conflicts and new fears Alan Parastaev Erman village in the high Caucasus mountains of South Ossetia PHOTO: PETER NASMYTH Summary The main source of weapons in South Ossetia during the conflict with Georgian forces in the early 1990s was Chechnya, but towards the end of the conflict arms were also obtained from Russian troops in North Ossetia. Following the end of the conflict in 1992, the unrecognised Republic of South Ossetia began to construct its own security structures. The government has made some attempts to control SALW proliferation and collect weapons from the population, as has the OSCE, though these programmes have had limited success. In North Ossetia it was much easier to acquire weapons from Russian military sources than in the South. North Ossetia fought a short war against the Ingush in 1992, and though relations between the two are now stable, North Ossetia is still very sensitive to events elsewhere in the North Caucasus. Recently, however, the increase in Russian military activity in the region has acted as a stabilising factor. Unofficial estimates of the amount of SALW in North Ossetia range between 20,000 and 50,000. 2 THE CAUCASUS: ARMED AND DIVIDED · NORTH AND SOUTH OSSETIA The years of The events at the end of the 1980s ushered in by perestroika – the move by the leader- conflict ship of the CPSU towards the democratisation of society – had an immediate impact on the social and political situation in South Ossetia and Georgia as a whole. In both Tbilisi and the South Ossetian capital Tskhinval national movements sprang to life which would in time evolve into political parties and associations. -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

The Analysis of Stereotypes of Politically Engaged Media Texts In

European Researcher, 2012, Vol.(35), № 11-3 UDC 372 The Analysis of Stereotypes of Politically Engaged Media Texts in Media Studies in Student Audience (by the Example of Renny Harlin’s films “Born American” (1986) and “Five Days of War” (2011) Alexander V. Fedorov Anton Chekhov Taganrog State Pedagogical Institute, Russia Iniciativnaya street 48, Taganrog city, Rostovskaya oblast, 347936 Dr. (Education), Professor E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The development of skills for the analysis of media texts is an important task of media education. However, media literacy practice shows that students have problems with the discussion / analysis of some genres in the early stages of media studies, for example, the difficulties in the process of understanding and interpreting the author's conception, plot and genre features. This article substantiates the methodological approaches to the analysis of politically engaged media texts in media studies in the student audience. Keywords: Media education; media literacy; media competence; media text; analysis; universities; students; media studies; film; cold war; policy; ideologies. Introduction. The famous British theorist of media education Len Masterman has repeatedly emphasized that it is necessary to teach the audience to understand the following: 1) who is responsible for the creation of media texts? who owns the media and controls them? 2) how is the effect achieved? 3) what value orientations are created? 4) how does the audience perceive it? [Masterman, 1985]. Of course, this kind of approach is mostly related to the texts which are outside the artistic sphere, and is not suitable for the outstanding works of media culture. However I think it is quite suitable for the opuses designed for mass audience, especially for the clearly politicized ones. -

Protection of Internally Displaced Persons in Georgia: a Gap Analysis

Protection of Internally Displaced Persons in Georgia: A Gap Analysis This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union. July 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................. 6 1. Context ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.1. Demographic profile .......................................................................................................................... 10 1.2. Meaningful participation.................................................................................................................... 10 1.3. Solution Oriented Approach .............................................................................................................. 11 1.5.1. Focus on return as the only durable solution ................................................................................. 11 1.5.2. Humanitarian space and access.....................................................................................................