CHAPTER I Historicizing 5 Days of War the Phrase the Historicity Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Register of Entertainers, Actors and Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa

Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1988_10 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 11/88 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1988-08-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1981 - 1988 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. REGISTER OF ENTERTAINERS, ACTORS AND OTHERS WHO HAVE PERFORMED IN APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA SINCE JANUARY 1981. -

October 23, 1993 . 2.95, US 5, ECU 4

Volume 10 . Issue 43 . October 23, 1993 . 2.95, US 5, ECU 4 AmericanRadioHistory.Com START SPREADING THE NEWS. CHARLES AZNAVOUR you make me feel so young ANITA BAKER witchcraft TONY BENNETT "new york, new york" BONO i've got you under my skin NATALIE COLE they can't take that away from me Frank Sinatra returns to the recording studio for the -first time in fifteen years. And he's GLORIA ESTEFAN come rain or come shine come home to the label and studio that are synonymous with the most prolific years of ARETHA FRANKLIN his extraordinary career. what now my love KENNY G Capitol Records proudly releases DUETS. all the way/one for my baby Thirteen new recordings of timeless Sinatra (and one more for the road) classics featuring the master of popular song JULIO IGLESIAS in vocal harmony with some of the world's summer wind greatest artists. LIZA MINNELLI. i've got the world on a string Once again, Sinatra re -invents his legend, and unites the generation gap, with a year's CARLY SIMON guess i'll hang my tears out to dry/ end collection of songs that make the perfect in the wee small hours of the morning holiday gift for any music fan. BARBRA STREISAND i've got a crush on you It's the recording event of the decade. LUTHER VANDROSS So start spreading the news. the lady is a tramp Produced by Phil Ramone and Hank Kattaneo Executive Producer: Don Rubin Released on October 25th Management: Premier Artists Services Recorded July -August 1993 CD MC LP EMI ) AmericanRadioHistory.Com . -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Diplomacy and Life on Georgia's Boundary Line Caecilia J. Van Peski 1

Diplomacy and life on Georgia’s boundary line Caecilia J. van Peski 1 Five days of war During the night of 7-8 August 2008, Georgia launched a large-scale military offensive against South Ossetia, in an attempt to reconquer the territory. Georgia claimed that it was responding to attacks on its peacekeepers and villages in South Ossetia, and that Russia was moving non-peacekeeping units into the country (Asmus, 2010).2 The Georgian attack caused casualties among Russian peacekeepers, who resisted the assault along with Ossetian militia. In the early hours of War, the Georgian army successfully captured most of Tskhinvali, the capital of South Ossetia. Russia reacted by deploying units of the Russian 58th Army and Russian Airborne Troops in South Ossetia, launching air strikes against Georgian forces in South Ossetia and military and logistical targets in Georgia proper. Russia claimed that these actions were a necessary humanitarian intervention and peace enforcement. Subsequently, Russian and Ossetian troops battled Georgian forces throughout South Ossetia for five days, with the heaviest fighting taking place in Tskhinvali. On August 9, Russian naval forces blockaded part of the Georgian coast and landed marines on the Abkhaz coast. The Georgian Navy attempted to intervene, but were defeated in a naval skirmish. Russian and Abkhaz forces then opened a second front by attacking the Kodori Gorge, held by Georgia.3 1 Caecilia J. van Peski is the founder of Van Peski Consult (www.vanpeskiconsult.org) and works as a policy officer for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In 2010, she was deployed to the Republic of Georgia as Deputy Team Leader Human Rights and Humanitarian Assistance within the European Union Monitoring Mission, EUMM. -

Instructions

MY DETAILS My Name: Jong B. Mobile No.: 0917-5877-393 Movie Library Count: 8,600 Titles / Movies Total Capacity : 36 TB Updated as of: December 30, 2014 Email Add.: jongb61yahoo.com Website: www.jongb11.weebly.com Sulit Acct.: www.jongb11.olx.ph Location Add.: Bago Bantay, QC. (Near SM North, LRT Roosevelt/Munoz Station & Congressional Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table Drive Capacity Loadable Space Est. No. of Movies/Titles 320 Gig 298 Gig 35+ Movies 500 Gig 462 Gig 70+ Movies 1 TB 931 Gig 120+ Movies 1.5 TB 1,396 Gig 210+ Movies 2 TB 1,860 Gig 300+ Movies 3 TB 2,740 Gig 410+ Movies 4 TB 3,640 Gig 510+ Movies Note: 1. 1st Come 1st Serve Policy 2. Number of Movies/Titles may vary depends on your selections 3. SD = Standard definition Instructions: 1. Please observe the Drive Capacity & Loadable/Free Space Table above 2. Mark your preferred titles with letter "X" only on the first column 3. Please do not make any modification on the list. 3. If you're done with your selections please email to [email protected] together with the confirmaton of your order. 4. Pls. refer to my location map under Contact Us of my website YOUR MOVIE SELECTIONS SUMMARY Categories No. of titles/items Total File Size Selected (In Gig.) Movies (2013 & Older) 0 0 2014 0 0 3D 0 0 Animations 0 0 Cartoon 0 0 TV Series 0 0 Korean Drama 0 0 Documentaries 0 0 Concerts 0 0 Entertainment 0 0 Music Video 0 0 HD Music 0 0 Sports 0 0 Adult 0 0 Tagalog 0 0 Must not be over than OVERALL TOTAL 0 0 the Loadable Space Other details: 1. -

Film Criticism

ALEXANDER FEDOROV FILM CRITICISM FEDOROV, A. FILM CRITICISM. МOSCOW: ICO “INFORMATION FOR ALL”. 2015. 382 P. COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY ALEXANDER FEDOROV [email protected] ALL RIGHT RESERVED. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 2 1 FEDOROV, ALEXANDER. 1954-. FILM CRITICISM / ALEXANDER FEDOROV. P. CM. INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES. 1. FILM CRITICISM. 2. FILM STUDIES. 3. MEDIA LITERACY. 4. MEDIA EDUCATION. 5. MEDIA STUDIES. 6. FILM EDUCATION. 7. STUDENTS. 8. CINEMA. 9. FILM. 10. MASS MEDIA. 11. STUDY AND TEACHING. 2 Contents The Mystery of Russian Cinema ………………………………..…... ..6 Phenomenon of Russian Film-Hits ………………………………….. 10 Russian Screen Distribution …………………………………..………..12 Video-pirates from Russia ……………………………………..…….. 15 Film Criticism and Press in Russia …………………………………… 17 Russian Cinematography and the Screen Violence ………………....….21 The Gloom of Russian Fantastic Movie-Land …………….………..….27 Sex-Cinema: Made in Russia …………………………………… ..….. 29 America, America… ……………………………………………….… .31 French Motives and Russian Melodies ………………………….…… .33 Fistful of Russian Movies ……………………………………….…… .41 Nikita Mikhalkov before XXI Century ………………………….…… 78 Karen Shakhnazarov: a Fortune's Favorite? ……………………….… 86 Pyotr Todorovsky: Dramatic Romance ……………………….……. 92 Oleg Kovalov, Former Film Critic .........................................................99 How to Shoot the “True” Film about Russia …………………………102 Locarno Film Fest: The View of a Film Educator ……………………103 The Analysis of Detective Genre at Film Education in Students’ Audience ……………………………………………… ……….…..106 Hermeneutical -

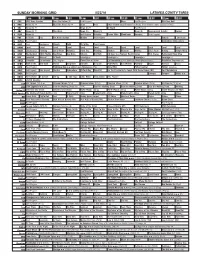

Sunday Morning Grid 5/22/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/22/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid 2016 French Open Tennis First Round. From Roland Garros Stadium in Paris. 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Supervisorial Debate Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program FabLab I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Somewhere Slow (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley Rick Steves Retirement Road Map 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho La Comadrita (1978, Comedia) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Firehouse Dog ›› (2007) Josh Hutcherson. -

DVD List As of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret

A LIST OF THE NEWEST DVDS IS LOCATED ON THE WALL NEXT TO THE DVD SHELVES DVD list as of 2/9/2013 2 Days in Paris 3 Idiots 4 Film Favorites(Secret Garden, The Witches, The Neverending Story, 5 Children & It) 5 Days of War 5th Quarter, The $5 A Day 8 Mile 9 10 Minute Solution-Quick Tummy Toners 10 Minute Solution-Dance off Fat Fast 10 Minute Solution-Hot Body Boot Camp 12 Men of Christmas 12 Rounds 13 Ghosts 15 Minutes 16 Blocks 17 Again 21 21 Jumpstreet (2012) 24-Season One 25 th Anniversary Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Concerts 28 Weeks Later 30 Day Shred 30 Minutes or Less 30 Years of National Geographic Specials 40-Year-Old-Virgin, The 50/50 50 First Dates 65 Energy Blasts 13 going on 30 27 Dresses 88 Minutes 102 Minutes That Changed America 127 Hours 300 3:10 to Yuma 500 Days of Summer 9/11 Commission Report 1408 2008 Beijing Opening Ceremony 2012 2016 Obama’s America A-Team, The ABCs- Little Steps Abandoned Abandoned, The Abduction About A Boy Accepted Accidental Husband, the Across the Universe Act of Will Adaptation Adjustment Bureau, The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D Adventures of Teddy Ruxpin-Vol 1 Adventures of TinTin, The Adventureland Aeonflux After.Life Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Murder of Roger Ackroyd Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Sad Cypress Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-The Hollow Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Five Little Pigs Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Lord Edgeware Dies Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Evil Under the Sun Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Murder in Mespotamia Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Death on the Nile Agatha Cristie’s Poirot-Taken at -

![CRISPR-Cas Arxiv:1712.09865V1 [Q-Bio.PE] 28 Dec 2017](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7770/crispr-cas-arxiv-1712-09865v1-q-bio-pe-28-dec-2017-2607770.webp)

CRISPR-Cas Arxiv:1712.09865V1 [Q-Bio.PE] 28 Dec 2017

The physicist's guide to one of biotechnology's hottest new topics: CRISPR-Cas Melia E. Bonomo1;3 and Michael W. Deem1;2;3 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA 2Department of Bioengineering, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA 3Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, Rice University, Houston, TX 77005, USA Abstract Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR- associated proteins (Cas) constitute a multi-functional, constantly evolving immune system in bacteria and archaea cells. A heritable, molecular memory is generated of phage, plasmids, or other mobile genetic elements that attempt to attack the cell. This memory is used to recognize and interfere with subsequent invasions from the same genetic elements. This versatile prokaryotic tool has also been used to advance applications in biotechnology. Here we review a large body of CRISPR-Cas research to explore themes of evolution and selection, population dynamics, horizontal gene transfer, specific and cross-reactive interactions, cost and regulation, as well as non- defensive CRISPR functions that boost host cell robustness. Physical understanding of the CRISPR-Cas system will advance applications, such as efficient and specific genetic engineering, cell labeling and information storage, and combating antibiotic resistance. 1 Introduction In 1987, Ishino and colleagues had set out to identify the encoded protein and primary structure of a particular gene in Escherichia coli by analyzing its chromosomal DNA seg- arXiv:1712.09865v1 [q-bio.PE] 28 Dec 2017 ment and flanking regions [1]. They found an interesting sequence structure at the gene's 3'-end flanking region, in which five homologous sequences of 29 nucleotides were arranged as direct repeats with 32-nucleotide sequences spaced between them. -

The Analysis of Stereotypes of Politically Engaged Media Texts In

European Researcher, 2012, Vol.(35), № 11-3 UDC 372 The Analysis of Stereotypes of Politically Engaged Media Texts in Media Studies in Student Audience (by the Example of Renny Harlin’s films “Born American” (1986) and “Five Days of War” (2011) Alexander V. Fedorov Anton Chekhov Taganrog State Pedagogical Institute, Russia Iniciativnaya street 48, Taganrog city, Rostovskaya oblast, 347936 Dr. (Education), Professor E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The development of skills for the analysis of media texts is an important task of media education. However, media literacy practice shows that students have problems with the discussion / analysis of some genres in the early stages of media studies, for example, the difficulties in the process of understanding and interpreting the author's conception, plot and genre features. This article substantiates the methodological approaches to the analysis of politically engaged media texts in media studies in the student audience. Keywords: Media education; media literacy; media competence; media text; analysis; universities; students; media studies; film; cold war; policy; ideologies. Introduction. The famous British theorist of media education Len Masterman has repeatedly emphasized that it is necessary to teach the audience to understand the following: 1) who is responsible for the creation of media texts? who owns the media and controls them? 2) how is the effect achieved? 3) what value orientations are created? 4) how does the audience perceive it? [Masterman, 1985]. Of course, this kind of approach is mostly related to the texts which are outside the artistic sphere, and is not suitable for the outstanding works of media culture. However I think it is quite suitable for the opuses designed for mass audience, especially for the clearly politicized ones. -

Künstlersozialabgabe Für Band-Unternehmer Und Orchester-Chefs

C 10973 F | No 2/20094/2008 | 3,00 Euro Künstlersozialabgabe Für Band-Unternehmer und Orchester-Chefs Modern Talking Legende & Wirklichkeit Pirate Bay Trotz Haftstrafe will Piratencrew nicht aufgeben SCUFX Deutscher Alternative Preisträger 2008 DIREKTVERSAND AN 18.000 MUSIKGRUPPEN & MUSIKER(INNEN) | VERKAUF AN ALLEN BAHNHOFS- & FLUGHAFENKIOSKEN & 130 MUSIKGESCHÄFTEN NEU Thomas Dill Jürgen Kumlehn Frank Haunschild Guitar Effects Die AMA-Gitarren- Let’s Groove! Vol. I Funktion und Einsatz von Grifftabelle Fun-Play-alongs for all Instruments, Effektgeräten für Gitarre. Das umfassende Akkordrepertoire Easy. Neuartige Play-along-Serie Best.-Nr. 610324 für Rock, Blues, Metal, Jazz etc. für alle Instrumente durch alle D 24,95 Best.-Nr. 610109 Stilrichtungen. Ein durchdachtes D 8,95 Band-Training-Konzept der Extraklasse! Best.-Nr. 610396 D 19,95 Jäcki Reznicek Peter Fischer Frank Haunschild Rock Bass Rock Guitar Basics Die neue Harmonielehre Das umfassende Lehrbuch Grundlegende Rockgitarren- Band I für den modernen E-Bassisten. methodik für Einsteiger und Seit Jahren ein musiktheoretisches Best.-Nr. 610108 Fortgeschrittene. Standardwerk für Schulen und D 24,95 Best.-Nr. 610143 Universitäten. D 29,95 Best.-Nr. 610101 D 19,95 Paul Westwood Peter Fischer Roman Schmon Bass Bible Masters Of Rock Guitar Das einfache Das ultimative Tipps und Tricks von 20 Drum-Spiel Nachschlagewerk. stilprägenden Gitarristen Patterns – Breaks – Best.-Nr. 610181 der 60er bis 90er Jahre. Soli – Konzepte D 38,95 Best.-Nr. 610105 Lehrbuch für Kinder und D 24,95 Erwachsene zum Erlernen des modernen Schlagzeugspiels. Best.-Nr. 610384 D 22,95 Karsten Sahling Billi Myer Dirk Brand Keyboard School Vocal Basics Pocket Rhythms Die bewährte AMA- Der Weg vom Sprechen For Drums Keyboardschule für alle zum Singen Millionenfache Übungsmöglich- Tasteninstrumente. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/11/2017 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/11/2017 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Shape of You - Ed Sheeran Someone Like You - Adele Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Piano Man - Billy Joel At Last - Etta James Don't Stop Believing - Journey Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Wannabe - Spice Girls Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Jackson - Johnny Cash Free Fallin' - Tom Petty Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Look What You Made Me Do - Taylor Swift I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Body Like a Back Road - Sam Hunt Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Santeria - Sublime Summer Nights - Grease Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Turn The Page - Bob Seger Zombie - The Cranberries Crazy - Patsy Cline Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Kryptonite - 3 Doors Down My Girl - The Temptations Despacito (Remix) - Luis Fonsi Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Let It Go - Idina Menzel Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Monster Mash - Bobby Boris Pickett Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's My Way - Frank Sinatra In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Rolling In The Deep - Adele All Of Me - John Legend These