Giuseppe Tornatore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Organized Crime: Camorra

PREGLEDNI ČLANCI UDK 343.974(450) Prihvaćeno: 12.9.2018. Elvio Ceci, PhD* The Constantinian University, New York ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZED CRIME: CAMORRA Abstract: Organized crime is a topic that deserves special attention, not just in criminal science. In this paper, the author analyzes Italian crime organizations in their origins, features and relationships between them. These organizations have similar patterns that we will show, but the main one is the division between government and governance. After the introductory part, the author gives a review of the genesis of the crime, but also of the main functions of criminal organizations: control of the territory, monopoly of violence, propensity for mediation and offensive capability. The author also described other organizations that act on the Italian soil (Cosa Nostra, ‘Ndrangheta, Napolitan Camora i Apulian Sacra Coroina Unita). The central focus of the paper is on the Napolitan mafia, Camorra, and its most famous representative – Cutolo. In this part of the paper, the author describes this organization from the following aspects: origin of Camorra, Cutulo and the New Organized Camorra, The decline of the New Organized Camorra and Cutolo: the figure of leader. Key words: mafia, governance, government, Camorra, smuggling. INTRODUCTION Referring to the “culturalist trend” in contemporary criminology, for which the “criminal issue” must include what people think about crime, certain analysts study- ing this trend, such as Benigno says, “it cannot be possible face independently to cultural processes which define it”.1 Concerning the birth of criminal organizations, a key break occured in 1876 when the left party won the election and the power of the State went to a new lead- ership. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

DB 2013 Katalog Prev

Sponsor Generalny Sponsor Ofi cjalny Hotel Festiwalu Ofi cjalny Samochód Festiwalu 2 Przyjaciele Festiwalu Partnerzy Organizatorzy Patronat Medialny Dofi nansowano ze środków Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego Projekt dofi nansowano ze środków Programu Operacyjnego Fundusz Inicjatyw Obywatelskich PGE 3 reklama Spis treści Sztuki wizualne Kto jest kto 6 Reżyser rysuje Podziękowania 9 wystawa rysunków Andrzeja Wajdy Słowo wstępne 11 z kolekcji Domu Aukcyjnego Abbey House S.A. 135 Kanał sztuki IV 136 Film „Hereditatis Paternae” wystawa malarstwa Jana Michalaka 137 Uroczystość Otwarcia 15 „Promień Światłospadu” Uroczystość Zamknięcia 17 Jerzy Krzysztoporski 138 Świat pod namiotem 18 „Lato w Kazimierzu i poezja” - Stanisław Ożóg 139 Pokazy specjalne 34 „Oblicza jazzu” wystawa fotografi i Katarzyny Rainka 140 Nagroda Filmowa Parlamentu Europejskiego LUX 34 „40 zdjęć na 40-lecie pracy w PWSFTviT” Lekcje kina 37 wystawa fotografi i prof. Aleksandra Błońskiego 141 Michael Haneke. Zawód: reżyser - pokaz fi lmu 37 „Fotoobrazy” - pokaz fi lmu artystycznego Waldemar Pokromski 39 prof. Mariusza Dąbrowskiego 142 Carlo di Carlo 40 „Kadry Rozpikselowane” Andrzej Jakimowski 42 Agata Dębicka 143 Wojciech Smarzowski 43 „Kultowe kino według Johansona” - Alex Johanson 144 Miasto 44 na DWÓCH BRZEGACH 45 „Classic Cinema” Robert Romanowicz (ilustracje), Na krótką metę 49 Paweł Bajew (fotografi a) 145 Janusz Morgenstern - Retrospektywa 51 „Wystawa setna pożegnalna” Thomas Vinterberg - Retrospektywa 59 Kolegium Sztuki UMCS Muzyka moja -

Tornatore: "Adesso Riparto Dalla Mia Sicilia"

Da http://www.lastampa.it/redazione/cmsSezioni/spettacoli/200811articoli/38252girata.asp#, 21 november 2008 16/11/2008 (8:58) - INTERVISTA Tornatore: "Adesso riparto dalla mia Sicilia" Vent’anni dopo l’Oscar, è il momento di “Baarìa” GIANCARLO DOTTO ROMA Il mio mestiere è quello d’inventare storie. Di scovarle, elaborarle, sognarle, scriverle e lasciarle nel cassetto. Ogni tanto accade un incidente di percorso e questo incidente è il film». Quando parla un siciliano che più siciliano non si può, tempo e spazio smettono di esistere. La parola Il regista Giuseppe Tornatore diventa meticoloso sfinimento. Peppino + CANALE Cinema e Tv Tornatore è una filtrazione gattopardesca, la versione aggiornata del principe di Salina. Due guardoni morbosi, che stiano a spiare stelle o facce umane poco importa. Che ci siano telescopi e lenti focali nel loro antro privato o vecchi arnesi di un cinema che non c’è più, proiettori, bobine da 35 millimetri, manifesti d’epoca. Due ore sono il tempo minimo per dirsi qualcosa di significativo e confermarsi nell’idea che il cinema, come qualunque altra mania, ha salvato un sacco di uomini dal baratro della malinconia. Tornatore si diffonde con generosa prudenza, non diffida dell’interlocutore ma delle parole, che scivolano spesso là dove lui non vorrebbe mai scivolare, l’enfasi, il luogo comune, la sciatta ripetizione. Sta finendo di montare Baarìa - La porta del vento, il suo ultimo, molto atteso film. Mi lascia sbirciare uno spot di tre minuti. Quanto basta per capire che sarà evocazione pura, quanto basta per riconoscere facce irriconoscibili. Fiorello, Frassica, Vincenzo Salemme, Ficarra e Picone. -

Riconoscersi Differenti Xxiii Festival Del Dialogo Interreligioso

IO SONO TU SEI RICONOSCERSI DIFFERENTI XXIII FESTIVAL DEL DIALOGO INTERRELIGIOSO ROMA 10 - 13 dicembre 2019 CASA DEL CINEMA Largo Marcello Mastroianni, 1 PRE APERTURA 3 dicembre 2019 CINEMA FARNESE Piazza Campo de’ Fiori, 56 IO SONO TU SEI RICONOSCERSI XXIII FESTIVAL DIFFERENTI DEL DIALOGO INTERRELIGIOSO ROMA 10 - 13 dicembre 2019 CASA DEL CINEMA Largo Marcello Mastroianni, 1 PRE APERTURA 3 dicembre 2019 CINEMA FARNESE Piazza Campo de’ Fiori, 56 Ingresso gratuito con prenotazione fino a esaurimento posti Informazioni e prenotazioni Tel. 06 96519200 [email protected] www.tertiomillenniofilmfest.org Fondazione Ente dello Spettacolo Tertio Millennio Film Fest Luca Baratto Coordinamento RdC Awards Delegato Associazione Valerio Sammarco Protestante Cinema Federico Pontiggia “Roberto Sbaffi” Contest cortometraggi Claudio Paravati Giacomo d’Alelio Direttore “Confronti”» Presidente ROMA Coordinamento editoria e web Mons. Davide Milani 3 dicembre 2019 Alexey Maksimov Alessandra Orlacchio Cinema Farnese Delegato Chiesa ortodossa russa Consiglio di amministrazione Testi 10-13 dicembre 2019 Mons. Davide Milani Ambra Tedeschi Lorenzo Ciofani Casa del Cinema Direttore Il Pitigliani Presidente Progetto grafico e immagine Centro Ebraico Italiano Antonio Ammirati Presidente coordinata Paolo Buzzonetti Mons. Davide Milani Sira Fatucci Adriano Attus e Marco Mezzadra Nicola Claudio Delegata Il Pitigliani Centro Direzione artistica Grafica Elisabetta Soglio Ebraico Italiano e UCEI Gianluca Arnone Marco Micci Collegio revisori conti Marina -

Malena Every Few Years Or So, a Modest Italian Movie Sidles Into

Malena Every few years or so, a modest Italian movie sidles into public consciousness and, through word of mouth, goes mainstream, enough so that even the multiplex masses are reading subtitles. In 1991 there was the Academy Award winner Mediterraneo which did good business. In 1995, Il Postino (The Postman) did even better, earning more money in the U.S. than any previous foreign-language film. In 1998, La Vita é Bella (Life is Beautiful) did even better boxoffice. One could say that this string of Italian hits began little more than ten years ago with Giuseppe Tornatore’s charming tale of Sicily Cinema Paradiso. Tornatore, a Sicilian himself (see interview below) has now returned with another Sicilian period piece, Malena, hoping no doubt for another success in the American. The film tells the story of the gloriously beautiful Malena Scordia (Monica Bellucci) during the early 1940’s in the Sicilian town (fictitious) of Castelcuto. Impeccably dressed but genuinely modest, she has every man in town panting for her and every woman in town despising her. Her husband is away at war, after all, and nobody has the right to look that good. Observing Malena from a distance--and worshiping her--is 13-year-old Renato (Giuseppe Sulfaro) who dreams of being her protector and who follows her every move (including spying on her home). After receiving word of the death of her husband, and after her doddering father comes to believe the worst rumors about her, Malena is left alone and destitute. She gradually yields to the inevitable male advances and eventually becomes a high-priced call girl for the occupying German troops. -

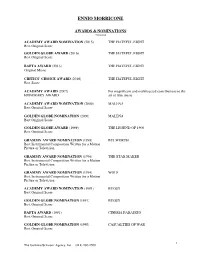

Ennio Morricone

ENNIO MORRICONE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS *selected ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2015) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Original Music CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Score ACADEMY AWARD (2007) For magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the HONORARY AWARD art of film music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best O riginal Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1999) THE LEGEND OF 1900 Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1998) BULWORTH Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) THE STAR MAKER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) WOLF Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1991) CINEMA PARADISO Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1990) CASUALTIES OF WAR Best Original Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 ENNIO MORRICONE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1987) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1987) THE MISSION Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1980) DAYS OF HEAVEN Anthony Asquith Award fo r Film Music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1979) DAYS OF HEAVEN Best Original Score MOTION PICTURES THE HATEFUL EIGHT Richard N. -

The Roots of the Organized Criminal Underworld in Campania

Sociology and Anthropology 1(2): 118-134, 2013 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/sa.2013.010211 The Roots of the Organized Criminal Underworld in Campania Pasquale Peluso Department of Public Politics and Administration Sciences, “Guglielmo Marconi” University, Rome, 00144, Italy *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright © 2013 Horizon Research Publishing All rights reserved. Abstract The Camorra is a closed sect that acts in the was born and how it has changed and developed over the shadows and does not collect and preserve documents that centuries, transforming from a rural Camorra to a can later be studied by scholars or researchers. It is hard to metropolitan one and finally to an entrepreneurial modern rebuild the history of the Camorra: the picture is fragmented, Camorra that uses different methods in order to manage its a mix of half-truths and legends. The aim of this article is to affairs threatening the nation. make a diachronic excursus in order to find out the origins of the Neapolitan Camorra, that has had a longer history than any of the other mafias, and to explain how this secret 2. Methodology organization has changed its main features from 1800 to the present and from the Bella Società Riformata to Nuova The research has suggested a detailed picture of the crime Camorra Organizzata. Finally the modern clans that fight to phenomenon and connected the study of a large number of keep the possession of their territory and operate like documents contrasting the Camorra and the careful financial holdings in order to improve their business assessment of sources about the topic. -

Il Camorrista Giuseppe Marrazzo

Il Camorrista Giuseppe Marrazzo Titolo: Il Camorrista Autore: Giuseppe Marrazzo Editore: Alessandro Polidoro Editore Collana: AltroParallelo Pagine: 250 c.a. Prezzo: 16€ Formato: 14x21 Uscita: aprile 2019 ISBN: 978-88-85737-23-5 Dopo trentacinque anni, ritorna in una nuova edizione Il Camorrista di Giuseppe Marrazzo, da cui il film di Giuseppe Tornatore, per rileggere, insieme al libro, il lavoro del grande giornalista, con l’intervento di numerosi protagonisti dell’epoca. Negli anni Settanta la Camorra, da fenomeno locale, si trasforma in una grande macchina di potere, una mostruosa piovra che allunga i suoi tentacoli su una intera regione con i suoi abitanti. L’artefice del cambiamento è Raffaele Cutolo, un ragazzo sconosciuto di Ottaviano, finito in galera dopo avere ucciso un uomo a seguito di un banale litigio. È proprio in carcere che Cutolo, giorno dopo giorno, costruisce il suo potere, il suo carisma, il suo ruolo “prestigioso” di capo di un’organizzazione che si estende in tutta Italia. La Nuova Camorra Organizzata sconvolge tutti i piani della malavita in Campania. Pone la sua pesante ipoteca sul traffico della droga, sul contrabbando delle sigarette, sulle estorsioni, sugli appalti. Il cervello di questa rivoluzione, che vede cadere migliaia di uomini in pochi anni, è lui, Raffaele Cutolo: “il professore”, “l’ingegnere”, “il messia”, l’abile manipolatore della fantasia popolare Giuseppe Marrazzo in questo libro avvincente come Il padrino, ma documentato sulle testimonianze dirette e le rivelazioni del protagonista, compone uno straordinario diario del “professore”; racconta i suoi delitti, i suoi traffici, gli amori, le debolezze, le trame oscure legate al clamoroso caso Cirillo, che vide Cutolo nei panni di mediatore fra lo Stato e i terroristi che avevano rapito l’assessore regionale campano. -

La Leggenda Del Pianista Sull'oceano (1998) a Baby Boy, Discovered In

La leggenda del pianista sull’oceano (1998) A baby boy, discovered in 1900 on an ocean liner, grows into a musical prodigy, never setting foot on land. Director: Giuseppe Tornatore Writers: Alessandro Baricco (monologue Novecento), Giuseppe Tornatore Stars: Tim Roth, Pruitt Taylor Vince, Mélanie Thierry Storyline: 1900. Danny Boodmann, a stoker on an American passenger liner, Virginian, finds a baby abandoned on the ship. He names the child Danny Boodmann T.D. Lemon Nineteen Hundred ‘1900’ and raises the child as his own until his death in an accident on the ship. The child never leaves the ship and turns out to be a musical genius, especially when it comes to playing the piano. As an adult he befriends a trumpet player in the ship’s band, Max Tooney. After several years on the ship Max leaves, and tells the story of 1900 to the owner of a music store. Awards - 22 wins and 9 nominations Golden Globes, USA 2000: Winner - Golden Globe Best Original Score - Motion Picture Ennio Morricone A wonderfully wistful mixture of melodrama and music. "The Legend of 1900" wistfully tells its creative, capriciously unpredictable, and musical tall tale with excellence in all aspects of film from sets to sound, costume to casting, and script to screenplay. Roth and Vince work well together in this plaintive, simple story which will captivate those who can make the leap of faith required to "buy in". A good film for all but critics, "Legend" will likely resonate most with those who equate living with musical expression. La vita è musica. -

August, 2007 19

August, 2007 19 LYRALEN KAYE (AFTRA/SAG) is a Meisner-trained actress who Some people coin the feeling as the "acting bug," but there's nothing buggy received her MFA Theatre from Sarah Lawrence College in 2002. She about it. The word that best describes what JUDITH KALAORA lives for as is seen regularly in Boston theatre and her credits include The Seagull an actress is "rush" - the thrill of adrenaline exploding inside and coming with Theatre Zone, Unveiling with Molasses Tank, Tomboy with J. Rene out of her body thru voice, expression and physicality. Her euphoria? Productions/NYC Fringe Festival, They Named Us Mary with PS Passing that rush to her audience. Judith’s career began at the age of nine. Films/ACP and numerous shows at the Devanaughn Theatre. Her film She was active in community theatre throughout her adolescence, and she credits include 27 Dresses with Columbia Pictures, Mama's Boy with Flancrest Films, and Escape graduated Syracuse University Magna cum Laude, receiving a BFA in from the Night with Smithline Films. Contact Lyralen at [email protected]. Acting and Spanish Literature & Language. She studied at the Shakespeare's Globe in London, and performed the role of Lady Macbeth ROBERT “Big Jake” JACOBS (AEA/SAG) has performed on on the Globe stage. Upon completion of her degree in '05, she returned to Broadway and in Regional and Stock Theatres throughout the East the Boston area and has become extremely involved in the theatre, television and film (feature & Coast; including: Worcester Foothills, Worcester Forum Theatre, Lyric indie) scenes. -

La Criminalità Napoletana Nel Cinema Italiano Degli Anni '70 E

Recibido: 12.3.2018 Aceptado: 14.4.2018 LA CRIMINALITÀ NAPOLETANA NEL CINEMA ITALIANO DEGLI ANNI ’70 E ’80 NEAPOLITAN CRIME IN 70S AND 80S ITALIAN FILM Paolino NAPPI* L’articolo prende in considerazione una parte della produzione cinematogra- fica che, tra gli anni Settanta e Ottanta del secolo scorso, ha rappresentato la criminalità napoletana. Dal poliziesco all’italiana al melodramma occhieg- giante alla sceneggiata di Pasquale Squitieri, fino all’impegno civile di Nanni Loy e Lina Wertmüller, i film analizzati giocano tra stereotipi ormai consoli- dati e la rappresentazione di un presente ―e di un futuro― all’insegna della negatività. Parole chiave: cinema italiano, criminalità, poliziesco, Napoli, camorra. This article considers a number of films which depicted Neapolitan crime in the Seventies and the Eighties. From Italian action movies to Pasquale Squi- tieri’s sceneggiata–melodrama and the social commitment cinema of Nanni Loy and Lina Wertmüller, the analysed works seem to play with some con- solidated stereotypes. At the same time, they attempt to convey a dark image of the present, and the future. Keywords: italian cinema, crime, crime drama, Naples, camorra. «La camorra è il mestiere del futuro» * Facultat de Filologia, Traducció i Comunicació. Universitat de València. Correspondencia: Universitat de València. Facultat de Filologia, Traducció i Comu- nicació. Avda. de Blasco Ibáñez 32. 46010 Valencia. España. e-mail: [email protected] Lıburna 12 [Mayo 2018], 73–96, ISSN: 1889-1128 Paolino NAPPI Introduzione no dei fenomeni più vistosi del cinema italiano degli anni Settanta è il grande successo popolare del film poliziesco, Utalvolta chiamato ―per rimarcarne la specificità italiana ri- spetto al modello americano― “poliziottesco”.