Malena Every Few Years Or So, a Modest Italian Movie Sidles Into

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Cinema As Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr

ENGL 2090: Italian Cinema as Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr. Lisa Verner [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys Italian cinema during the postwar period, charting the rise and fall of neorealism after the fall of Mussolini. Neorealism was a response to an existential crisis after World War II, and neorealist films featured stories of the lower classes, the poor, and the oppressed and their material and ethical struggles. After the fall of Mussolini’s state sponsored film industry, filmmakers filled the cinematic void with depictions of real life and questions about Italian morality, both during and after the war. This class will chart the rise of neorealism and its later decline, to be replaced by films concerned with individual, as opposed to national or class-based, struggles. We will consider the films in their historical contexts as literary art forms. REQUIRED TEXTS: Rome, Open City, director Roberto Rossellini (1945) La Dolce Vita, director Federico Fellini (1960) Cinema Paradiso, director Giuseppe Tornatore (1988) Life is Beautiful, director Roberto Benigni (1997) Various articles for which the instructor will supply either a link or a copy in an email attachment LEARNING OUTCOMES: At the completion of this course, students will be able to 1-understand the relationship between Italian post-war cultural developments and the evolution of cinema during the latter part of the 20th century; 2-analyze film as a form of literary expression; 3-compose critical and analytical papers that explore film as a literary, artistic, social and historical construct. GRADES: This course will require weekly short papers (3-4 pages, double spaced, 12- point font); each @ 20% of final grade) and a final exam (20% of final grade). -

Analysis of Organized Crime: Camorra

PREGLEDNI ČLANCI UDK 343.974(450) Prihvaćeno: 12.9.2018. Elvio Ceci, PhD* The Constantinian University, New York ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZED CRIME: CAMORRA Abstract: Organized crime is a topic that deserves special attention, not just in criminal science. In this paper, the author analyzes Italian crime organizations in their origins, features and relationships between them. These organizations have similar patterns that we will show, but the main one is the division between government and governance. After the introductory part, the author gives a review of the genesis of the crime, but also of the main functions of criminal organizations: control of the territory, monopoly of violence, propensity for mediation and offensive capability. The author also described other organizations that act on the Italian soil (Cosa Nostra, ‘Ndrangheta, Napolitan Camora i Apulian Sacra Coroina Unita). The central focus of the paper is on the Napolitan mafia, Camorra, and its most famous representative – Cutolo. In this part of the paper, the author describes this organization from the following aspects: origin of Camorra, Cutulo and the New Organized Camorra, The decline of the New Organized Camorra and Cutolo: the figure of leader. Key words: mafia, governance, government, Camorra, smuggling. INTRODUCTION Referring to the “culturalist trend” in contemporary criminology, for which the “criminal issue” must include what people think about crime, certain analysts study- ing this trend, such as Benigno says, “it cannot be possible face independently to cultural processes which define it”.1 Concerning the birth of criminal organizations, a key break occured in 1876 when the left party won the election and the power of the State went to a new lead- ership. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

California State University, Sacramento Department of World Literatures and Languages Italian 104 a INTRODUCTION to ITALIAN CINEMA I GE Area C1 SPRING 2017

1 California State University, Sacramento Department of World Literatures and Languages Italian 104 A INTRODUCTION TO ITALIAN CINEMA I GE Area C1 SPRING 2017 Course Hours: Wednesdays 5:30-8:20 Course Location: Mariposa 2005 Course Instructor: Professor Barbara Carle Office Location: Mariposa Hall 2057 Office Hours: W 2:30-3:30, TR 5:20-6:20 and by appointment CATALOG DESCRIPTION ITAL 104A. Introduction to Italian Cinema I. Italian Cinema from the 1940's to its Golden Period in the 1960's through the 1970's. Films will be viewed in their cultural, aesthetic and/or historical context. Readings and guiding questionnaires will help students develop appropriate viewing skills. Films will be shown in Italian with English subtitles. Graded: Graded Student. Units: 3.0 COURSE GOALS and METHODS: To develop a critical knowledge of Italian film history and film techniques and an aesthetic appreciation for cinema, attain more than a mere acquaintance or a broad understanding of specific artistic (cinematographic) forms, genres, and cultural sources, that is, to learn about Italian civilization (politics, art, theatre and customs) through cinema. Guiding questionnaires will also be distributed on a regular basis to help students achieve these goals. All questionnaires will be graded. Weekly discussions will help students appreciate connections between cinema and art and literary movements, between Italian cinema and American film, as well as to deal with questionnaires. You are required to view the films in the best possible conditions, i.e. on a large screen in class. Viewing may be enjoyable but is not meant to be exclusively entertaining. -

1 Cinema Paradiso and Malèna (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1989, 2000)

1 Cinema Paradiso and Malèna (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1989, 2000) The big question is, how, if he had to keep all the kisses the priest censored, and re-splice them into the print when it went off to its next booking, did Alfredo manage also to store them in the projection booth? It’s true that you sometimes see prints with bits missing. I once got five free tickets to the Cambridge Arts after complaining that a print we’d seen of La Grande Illusion lacked the moment when Pierre Fresnay was shot, and lacked the last bit of the last shot, when Gabin and Carette escape over the Swiss border. But that was a one-off – if the Sicilian distributors here got lots of complaints about missing snogs from cinemas all over the mezzogiorno, surely they’d soon work out who was pinching them, and demand his dismissal? This doubt, together with Morricone’s revoltingly sentimental and repetitive score, ruins the end of the film for me, whichever cut I see it in. —————————— Cinema is paradise. It brings community together, and renders misbehaviour unacceptable – boorish people who barge in yelling are pelted and booed, and the bourgeois in the circle who spits on the plebs below finally gets poo thrown in his face. The local mafia head is shot right at the correct point in (what seems to me) Howard Hawks’ Scarface . The priest, initially outraged by the medium’s excesses, is (you can see) seduced and won over by it. Like Tony Curtis on board his warship with only Gunga Din to watch, you learn all the dialogue, and it becomes your alternative life. -

DB 2013 Katalog Prev

Sponsor Generalny Sponsor Ofi cjalny Hotel Festiwalu Ofi cjalny Samochód Festiwalu 2 Przyjaciele Festiwalu Partnerzy Organizatorzy Patronat Medialny Dofi nansowano ze środków Ministra Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego Projekt dofi nansowano ze środków Programu Operacyjnego Fundusz Inicjatyw Obywatelskich PGE 3 reklama Spis treści Sztuki wizualne Kto jest kto 6 Reżyser rysuje Podziękowania 9 wystawa rysunków Andrzeja Wajdy Słowo wstępne 11 z kolekcji Domu Aukcyjnego Abbey House S.A. 135 Kanał sztuki IV 136 Film „Hereditatis Paternae” wystawa malarstwa Jana Michalaka 137 Uroczystość Otwarcia 15 „Promień Światłospadu” Uroczystość Zamknięcia 17 Jerzy Krzysztoporski 138 Świat pod namiotem 18 „Lato w Kazimierzu i poezja” - Stanisław Ożóg 139 Pokazy specjalne 34 „Oblicza jazzu” wystawa fotografi i Katarzyny Rainka 140 Nagroda Filmowa Parlamentu Europejskiego LUX 34 „40 zdjęć na 40-lecie pracy w PWSFTviT” Lekcje kina 37 wystawa fotografi i prof. Aleksandra Błońskiego 141 Michael Haneke. Zawód: reżyser - pokaz fi lmu 37 „Fotoobrazy” - pokaz fi lmu artystycznego Waldemar Pokromski 39 prof. Mariusza Dąbrowskiego 142 Carlo di Carlo 40 „Kadry Rozpikselowane” Andrzej Jakimowski 42 Agata Dębicka 143 Wojciech Smarzowski 43 „Kultowe kino według Johansona” - Alex Johanson 144 Miasto 44 na DWÓCH BRZEGACH 45 „Classic Cinema” Robert Romanowicz (ilustracje), Na krótką metę 49 Paweł Bajew (fotografi a) 145 Janusz Morgenstern - Retrospektywa 51 „Wystawa setna pożegnalna” Thomas Vinterberg - Retrospektywa 59 Kolegium Sztuki UMCS Muzyka moja -

Tornatore: "Adesso Riparto Dalla Mia Sicilia"

Da http://www.lastampa.it/redazione/cmsSezioni/spettacoli/200811articoli/38252girata.asp#, 21 november 2008 16/11/2008 (8:58) - INTERVISTA Tornatore: "Adesso riparto dalla mia Sicilia" Vent’anni dopo l’Oscar, è il momento di “Baarìa” GIANCARLO DOTTO ROMA Il mio mestiere è quello d’inventare storie. Di scovarle, elaborarle, sognarle, scriverle e lasciarle nel cassetto. Ogni tanto accade un incidente di percorso e questo incidente è il film». Quando parla un siciliano che più siciliano non si può, tempo e spazio smettono di esistere. La parola Il regista Giuseppe Tornatore diventa meticoloso sfinimento. Peppino + CANALE Cinema e Tv Tornatore è una filtrazione gattopardesca, la versione aggiornata del principe di Salina. Due guardoni morbosi, che stiano a spiare stelle o facce umane poco importa. Che ci siano telescopi e lenti focali nel loro antro privato o vecchi arnesi di un cinema che non c’è più, proiettori, bobine da 35 millimetri, manifesti d’epoca. Due ore sono il tempo minimo per dirsi qualcosa di significativo e confermarsi nell’idea che il cinema, come qualunque altra mania, ha salvato un sacco di uomini dal baratro della malinconia. Tornatore si diffonde con generosa prudenza, non diffida dell’interlocutore ma delle parole, che scivolano spesso là dove lui non vorrebbe mai scivolare, l’enfasi, il luogo comune, la sciatta ripetizione. Sta finendo di montare Baarìa - La porta del vento, il suo ultimo, molto atteso film. Mi lascia sbirciare uno spot di tre minuti. Quanto basta per capire che sarà evocazione pura, quanto basta per riconoscere facce irriconoscibili. Fiorello, Frassica, Vincenzo Salemme, Ficarra e Picone. -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

Italian (ITAL) 1

Italian (ITAL) 1 ITAL 104B. Introduction to Italian Cinema II. 3 Units ITALIAN (ITAL) Term Typically Offered: Fall, Spring ITAL 1A. Elementary Italian. 4 Units Focuses on Italian Cinema from the 1980's and the 1990's. The "New Term Typically Offered: Fall only Generation" of Italian Directors will be considered (Nanni Moretti, Gabriele Salvatores, Maurizio Nichetti, Giuseppe Tornatore, Roberto Benigni, Liliani Focuses on the development of the four basic skills (understanding, Cavani, Fiorenza Infascelli, Francesca Archibugi, etc.) as well as current speaking, reading, writing) through the presentation of many cultural productions. Films will be shown in Italian with English subtitles. components (two per week) which illustrate the Italian "modus vivendi:" ITAL 110. Introduction to Italian Literature I. 3 Units social issues, family, food, sports, etc. Prerequisite(s): Upper division status and instructor permission. ITAL 1B. Elementary Italian. 4 Units Term Typically Offered: Fall only Prerequisite(s): ITAL 1A or instructor permission. General Education Area/Graduation Requirement: Humanities (Area C2), Beginning and major developments of the literature of Italy from the Foreign Language Graduation Requirement Middle Ages through the Baroque period of the 17th Century. Analyzes Term Typically Offered: Fall, Spring the literary movements with emphasis on their leading figures, discussion of literary subjects, instruction in the preparation of reports on literary, Continuation of ITAL 1A with greater emphasis on reading, writing. biographical and cultural topics. Taught in Italian. Addition of one reader which contains more cultural material (geography, ITAL 111. Introduction to Italian Literature II. 3 Units political issues, government, fashion, etc.). Prerequisite(s): Upper division standing and instructor permission. -

Riconoscersi Differenti Xxiii Festival Del Dialogo Interreligioso

IO SONO TU SEI RICONOSCERSI DIFFERENTI XXIII FESTIVAL DEL DIALOGO INTERRELIGIOSO ROMA 10 - 13 dicembre 2019 CASA DEL CINEMA Largo Marcello Mastroianni, 1 PRE APERTURA 3 dicembre 2019 CINEMA FARNESE Piazza Campo de’ Fiori, 56 IO SONO TU SEI RICONOSCERSI XXIII FESTIVAL DIFFERENTI DEL DIALOGO INTERRELIGIOSO ROMA 10 - 13 dicembre 2019 CASA DEL CINEMA Largo Marcello Mastroianni, 1 PRE APERTURA 3 dicembre 2019 CINEMA FARNESE Piazza Campo de’ Fiori, 56 Ingresso gratuito con prenotazione fino a esaurimento posti Informazioni e prenotazioni Tel. 06 96519200 [email protected] www.tertiomillenniofilmfest.org Fondazione Ente dello Spettacolo Tertio Millennio Film Fest Luca Baratto Coordinamento RdC Awards Delegato Associazione Valerio Sammarco Protestante Cinema Federico Pontiggia “Roberto Sbaffi” Contest cortometraggi Claudio Paravati Giacomo d’Alelio Direttore “Confronti”» Presidente ROMA Coordinamento editoria e web Mons. Davide Milani 3 dicembre 2019 Alexey Maksimov Alessandra Orlacchio Cinema Farnese Delegato Chiesa ortodossa russa Consiglio di amministrazione Testi 10-13 dicembre 2019 Mons. Davide Milani Ambra Tedeschi Lorenzo Ciofani Casa del Cinema Direttore Il Pitigliani Presidente Progetto grafico e immagine Centro Ebraico Italiano Antonio Ammirati Presidente coordinata Paolo Buzzonetti Mons. Davide Milani Sira Fatucci Adriano Attus e Marco Mezzadra Nicola Claudio Delegata Il Pitigliani Centro Direzione artistica Grafica Elisabetta Soglio Ebraico Italiano e UCEI Gianluca Arnone Marco Micci Collegio revisori conti Marina -

Nuovo Cinema Paradiso (1988) Director: Giuseppe Tornatore Writers: Giuseppe Tornatore (Story), Giuseppe Tornatore (Screenplay)

Nuovo cinema Paradiso (1988) Director: Giuseppe Tornatore Writers: Giuseppe Tornatore (story), Giuseppe Tornatore (screenplay) Stars: Philippe Noiret, Enzo Cannavale, Antonella Attili Cannes Film Festival 1989 – Winner – Grand Prize of the Jury Giuseppe Tornatore Academy Awards, USA 1990 – Winner – Oscar Best Foreign Language Film Plot A boy who grew up in a native Sicilian Village returns home as a famous director after receiving news about the death of an old friend. Told in a flashback, Salvatore reminiscences about his childhood and his relationship with Alfredo, a projectionist at Cinema Paradiso. Under the fatherly influence of Alfredo, Salvatore fell in love with film making, with the duo spending many hours discussing about films and Alfredo painstakingly teaching Salvatore the skills that became a stepping stone for the young boy into the world of film making. The film brings the audience through the changes in cinema and the dying trade of traditional film making, editing and screening. It also explores a young boy’s dream of leaving his little town to foray into the world outside. The movie opens with Salvatore’s mother trying to inform him of the death of Alfredo. Salvatore, a filmmaker who has not been home since his youth, leaves Rome immediately to attend the funeral. Through flashbacks we watch Salvatore in his youth, in a post WWII town in Southern Italy. As a young boy he is called Toto and he has a strong affinity for the cinema. Toto often sneaks into the movie theater when he shouldn’t and harasses the projectionist, Alfredo, in attempts to get splices of film that are cut out by the church because they contain scenes of kissing. -

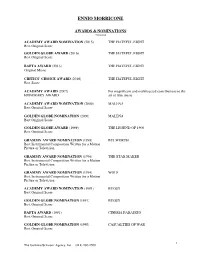

Ennio Morricone

ENNIO MORRICONE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS *selected ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2015) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Original Music CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Score ACADEMY AWARD (2007) For magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the HONORARY AWARD art of film music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best O riginal Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1999) THE LEGEND OF 1900 Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1998) BULWORTH Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) THE STAR MAKER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) WOLF Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1991) CINEMA PARADISO Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1990) CASUALTIES OF WAR Best Original Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 ENNIO MORRICONE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1987) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1987) THE MISSION Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1980) DAYS OF HEAVEN Anthony Asquith Award fo r Film Music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1979) DAYS OF HEAVEN Best Original Score MOTION PICTURES THE HATEFUL EIGHT Richard N.