1 Cinema Paradiso and Malèna (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1989, 2000)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Italian Cinema As Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr

ENGL 2090: Italian Cinema as Literary Art UNO Rome Summer Study Abroad 2019 Dr. Lisa Verner [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION: This course surveys Italian cinema during the postwar period, charting the rise and fall of neorealism after the fall of Mussolini. Neorealism was a response to an existential crisis after World War II, and neorealist films featured stories of the lower classes, the poor, and the oppressed and their material and ethical struggles. After the fall of Mussolini’s state sponsored film industry, filmmakers filled the cinematic void with depictions of real life and questions about Italian morality, both during and after the war. This class will chart the rise of neorealism and its later decline, to be replaced by films concerned with individual, as opposed to national or class-based, struggles. We will consider the films in their historical contexts as literary art forms. REQUIRED TEXTS: Rome, Open City, director Roberto Rossellini (1945) La Dolce Vita, director Federico Fellini (1960) Cinema Paradiso, director Giuseppe Tornatore (1988) Life is Beautiful, director Roberto Benigni (1997) Various articles for which the instructor will supply either a link or a copy in an email attachment LEARNING OUTCOMES: At the completion of this course, students will be able to 1-understand the relationship between Italian post-war cultural developments and the evolution of cinema during the latter part of the 20th century; 2-analyze film as a form of literary expression; 3-compose critical and analytical papers that explore film as a literary, artistic, social and historical construct. GRADES: This course will require weekly short papers (3-4 pages, double spaced, 12- point font); each @ 20% of final grade) and a final exam (20% of final grade). -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

California State University, Sacramento Department of World Literatures and Languages Italian 104 a INTRODUCTION to ITALIAN CINEMA I GE Area C1 SPRING 2017

1 California State University, Sacramento Department of World Literatures and Languages Italian 104 A INTRODUCTION TO ITALIAN CINEMA I GE Area C1 SPRING 2017 Course Hours: Wednesdays 5:30-8:20 Course Location: Mariposa 2005 Course Instructor: Professor Barbara Carle Office Location: Mariposa Hall 2057 Office Hours: W 2:30-3:30, TR 5:20-6:20 and by appointment CATALOG DESCRIPTION ITAL 104A. Introduction to Italian Cinema I. Italian Cinema from the 1940's to its Golden Period in the 1960's through the 1970's. Films will be viewed in their cultural, aesthetic and/or historical context. Readings and guiding questionnaires will help students develop appropriate viewing skills. Films will be shown in Italian with English subtitles. Graded: Graded Student. Units: 3.0 COURSE GOALS and METHODS: To develop a critical knowledge of Italian film history and film techniques and an aesthetic appreciation for cinema, attain more than a mere acquaintance or a broad understanding of specific artistic (cinematographic) forms, genres, and cultural sources, that is, to learn about Italian civilization (politics, art, theatre and customs) through cinema. Guiding questionnaires will also be distributed on a regular basis to help students achieve these goals. All questionnaires will be graded. Weekly discussions will help students appreciate connections between cinema and art and literary movements, between Italian cinema and American film, as well as to deal with questionnaires. You are required to view the films in the best possible conditions, i.e. on a large screen in class. Viewing may be enjoyable but is not meant to be exclusively entertaining. -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

Italian (ITAL) 1

Italian (ITAL) 1 ITAL 104B. Introduction to Italian Cinema II. 3 Units ITALIAN (ITAL) Term Typically Offered: Fall, Spring ITAL 1A. Elementary Italian. 4 Units Focuses on Italian Cinema from the 1980's and the 1990's. The "New Term Typically Offered: Fall only Generation" of Italian Directors will be considered (Nanni Moretti, Gabriele Salvatores, Maurizio Nichetti, Giuseppe Tornatore, Roberto Benigni, Liliani Focuses on the development of the four basic skills (understanding, Cavani, Fiorenza Infascelli, Francesca Archibugi, etc.) as well as current speaking, reading, writing) through the presentation of many cultural productions. Films will be shown in Italian with English subtitles. components (two per week) which illustrate the Italian "modus vivendi:" ITAL 110. Introduction to Italian Literature I. 3 Units social issues, family, food, sports, etc. Prerequisite(s): Upper division status and instructor permission. ITAL 1B. Elementary Italian. 4 Units Term Typically Offered: Fall only Prerequisite(s): ITAL 1A or instructor permission. General Education Area/Graduation Requirement: Humanities (Area C2), Beginning and major developments of the literature of Italy from the Foreign Language Graduation Requirement Middle Ages through the Baroque period of the 17th Century. Analyzes Term Typically Offered: Fall, Spring the literary movements with emphasis on their leading figures, discussion of literary subjects, instruction in the preparation of reports on literary, Continuation of ITAL 1A with greater emphasis on reading, writing. biographical and cultural topics. Taught in Italian. Addition of one reader which contains more cultural material (geography, ITAL 111. Introduction to Italian Literature II. 3 Units political issues, government, fashion, etc.). Prerequisite(s): Upper division standing and instructor permission. -

Nuovo Cinema Paradiso (1988) Director: Giuseppe Tornatore Writers: Giuseppe Tornatore (Story), Giuseppe Tornatore (Screenplay)

Nuovo cinema Paradiso (1988) Director: Giuseppe Tornatore Writers: Giuseppe Tornatore (story), Giuseppe Tornatore (screenplay) Stars: Philippe Noiret, Enzo Cannavale, Antonella Attili Cannes Film Festival 1989 – Winner – Grand Prize of the Jury Giuseppe Tornatore Academy Awards, USA 1990 – Winner – Oscar Best Foreign Language Film Plot A boy who grew up in a native Sicilian Village returns home as a famous director after receiving news about the death of an old friend. Told in a flashback, Salvatore reminiscences about his childhood and his relationship with Alfredo, a projectionist at Cinema Paradiso. Under the fatherly influence of Alfredo, Salvatore fell in love with film making, with the duo spending many hours discussing about films and Alfredo painstakingly teaching Salvatore the skills that became a stepping stone for the young boy into the world of film making. The film brings the audience through the changes in cinema and the dying trade of traditional film making, editing and screening. It also explores a young boy’s dream of leaving his little town to foray into the world outside. The movie opens with Salvatore’s mother trying to inform him of the death of Alfredo. Salvatore, a filmmaker who has not been home since his youth, leaves Rome immediately to attend the funeral. Through flashbacks we watch Salvatore in his youth, in a post WWII town in Southern Italy. As a young boy he is called Toto and he has a strong affinity for the cinema. Toto often sneaks into the movie theater when he shouldn’t and harasses the projectionist, Alfredo, in attempts to get splices of film that are cut out by the church because they contain scenes of kissing. -

Malena Every Few Years Or So, a Modest Italian Movie Sidles Into

Malena Every few years or so, a modest Italian movie sidles into public consciousness and, through word of mouth, goes mainstream, enough so that even the multiplex masses are reading subtitles. In 1991 there was the Academy Award winner Mediterraneo which did good business. In 1995, Il Postino (The Postman) did even better, earning more money in the U.S. than any previous foreign-language film. In 1998, La Vita é Bella (Life is Beautiful) did even better boxoffice. One could say that this string of Italian hits began little more than ten years ago with Giuseppe Tornatore’s charming tale of Sicily Cinema Paradiso. Tornatore, a Sicilian himself (see interview below) has now returned with another Sicilian period piece, Malena, hoping no doubt for another success in the American. The film tells the story of the gloriously beautiful Malena Scordia (Monica Bellucci) during the early 1940’s in the Sicilian town (fictitious) of Castelcuto. Impeccably dressed but genuinely modest, she has every man in town panting for her and every woman in town despising her. Her husband is away at war, after all, and nobody has the right to look that good. Observing Malena from a distance--and worshiping her--is 13-year-old Renato (Giuseppe Sulfaro) who dreams of being her protector and who follows her every move (including spying on her home). After receiving word of the death of her husband, and after her doddering father comes to believe the worst rumors about her, Malena is left alone and destitute. She gradually yields to the inevitable male advances and eventually becomes a high-priced call girl for the occupying German troops. -

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY , Florence Italy Fall 2010 Syllabus for History of Italian Cinema

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY , Florence Italy Fall 2010 Syllabus for History of Italian Cinema Class Meetings: Wednesdays 4:30-7:15 pm Screenings: Film Screenings: Monday or Tuesday 6:00-8:00 pm Professor: Tina Fallani Benaim [email protected] Office Hours: after class or by appointment Required Reading: Peter Bondanella: Italian Cinema (Continuum Third Edition 2003) Millicent Marcus: In the Light of Neorealism (Princeton university Press 1986) Chapters 1,2,6, included in the Course Reader Packet of Articles and Reviews in the Course Reader (see weekly calendar) that includes Essays by: Bazin, Burke, Chatman, Michaiczyck Assignments: Attendance to lectures and screenings One midterm paper and a final test (essay questions) covering the entire program Oral presentations Grading System: Participation 20% Oral Presentations 20% Mid-term exam 25% Final Exam 35% Course description The course introduces the student to the world of Italian Cinema. In the first part the class will be analysing Neorealism , a cinematic phenomenon that deeply influenced the ideological and aesthetic rules of film art. In the second part we will concentrate on the films that mark the decline of Neorealism and the talent of "new" auteurs such as Fellini and Antonioni . The last part of the course will be devoted to the cinema from 1970's to the present in order to pay attention to the latest developments of the Italian industry. The course is a general 1 1 analysis of post-war cinema and a parallel social history of this period using films as "decoded historical evidence". Together with masterpieces such as "Open City" and "The Bicycle Thief" the screenings will include films of the Italian directors of the "cinema d'autore" such as "The Conformist", "Life is Beautiful" and the 2004 candidate for the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, “I am not scared”. -

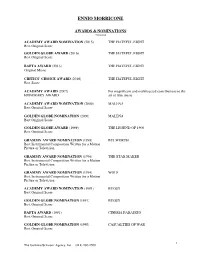

Ennio Morricone

ENNIO MORRICONE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS *selected ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2015) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Original Music CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Score ACADEMY AWARD (2007) For magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the HONORARY AWARD art of film music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best O riginal Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1999) THE LEGEND OF 1900 Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1998) BULWORTH Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) THE STAR MAKER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) WOLF Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1991) CINEMA PARADISO Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1990) CASUALTIES OF WAR Best Original Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 ENNIO MORRICONE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1987) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1987) THE MISSION Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1980) DAYS OF HEAVEN Anthony Asquith Award fo r Film Music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1979) DAYS OF HEAVEN Best Original Score MOTION PICTURES THE HATEFUL EIGHT Richard N. -

The Kinship Between Cinema Paradiso and Zıkkımın Kökü, Karpuz Kabuğundan Gemiler Yapmak, Sinema Bir Mucizedir

CINEMA ON CINEMA : The Kinship between Cinema Paradiso and Zıkkımın Kökü, Karpuz Kabuğundan Gemiler Yapmak, Sinema Bir Mucizedir Basak Demiray Volume 1.1 (2011): 31-38 | ISSN 2159-2411(print) 2158-8724(online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2011.10 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract This study consists of a comparative analysis of four films which fall under the category of “cinema on cinema”. These films are Cinema Paradiso (Giuseppe Tornatore, 1988, Italy), Zıkkımın Kökü (Memduh Ün, 1993, Turkey), Karpuz Kabuğundan Gemiler Yapmak/ Boats out of Watermelon Rinds ( Ahmet Uluçay, 2004, Turkey), Sinema Bir Mucizedir/ Cinema is a Miracle (Memduh Ün- Tunç Başaran, 2005, Turkey). It will be argued that these films have four main points of similarity. First, they are the instances of “cinema on cinema”; second, they are biographical films; third, their plots are constructed upon the rural lives of the past; fourth, they are about cinephilia. Keywords: cinema on cinema, metafilm, micro-history, cinephilia, biographical film This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. CINEMA ON CINEMA : The Kinship between Cinema Paradiso and Zıkkımın Kökü, Karpuz Kabuğundan Gemiler Yapmak, Sinema Bir Mucizedir “Life is not like the movies” says Alfredo the projectionist, in Giuseppe Tornatore‟s Cinema Paradiso (1988, Italy). On the contrary, „the movies‟ including Cinema Paradiso and Zıkkımın Kökü (Memduh Ün, 1993, Turkey), Karpuz Kabuğundan Gemiler Yapmak/ Boats out of Watermelon Rinds ( Ahmet Uluçay, 2004, Turkey), Sinema Bir Mucizedir/ Cinema is a Miracle (Memduh Ün- Tunç Başaran, 2005, Turkey) are like „the life‟. -

Peter Bondanella

35 Peter Bondanella LA PRESENZA DI FELLINI NEL CINEMA CONTEMPORANEO: CONSIDERAZIONI PRELIMINARI PETER BONDANELLA Valutare l’impatto di Federico sa tematica in modi magari popolare dopo il successo del Fellini sul cinema mondiale molto diversi. film), ma lucertoloni. appena una decade dopo la Come lucertole, i perdigiorno sua morte non può certamente provinciali della Wertmüller condurre a conclusioni defini- Il cinema di Fellini come arrostiscono al sole sulle me- tive, visto che il raggio della magazzino di facce, immagini taforiche pietre della loro pic- sua influenza sulle cinema- e sequenze: Martin Scorsese, cola città, e, come il Moraldo tografie o sui registi di altre Lina Wertmüller, Peter di Fellini, l’unico vitellone che nazioni nonché quella sulla Greenaway, Giuseppe sembra capace di scuotersi dal pop-culture, sulla pubblicità e Tornatore, Joel Schumacher suo provinciale letargo, Anto- sul folklore comincia a chia- e Bob Fosse. nio (Antonio Petruzzi) si con- rirsi nettamente solo adesso. fronta con Roma in una breve Tenterò dunque di illustrare L’analisi dell’impatto dei visita, durante la quale accom- alcuni dei più importanti e film di Fellini su specifiche pagna due zie nella capitale. interessanti esempi della sua sequenze o situazioni di film, Una volta tornato a casa, influenza su differenti tipi rivela che un insieme di regi- l’energia che questi sembrava di cinema e su registi molto sti piuttosto differenti fra loro assorbire dalla Città Eterna diversi, appartenenti ad altre ha reso omaggio all’opera di svanisce di giorno in giorno e cinematografie nazionali. È Fellini. Antonio finisce per rimandare inutile dire che le mie osserva- Cronologicamente, il primo senza fine la sua partenza dal- zioni mirano solo ad aprire un successo commerciale di Felli- la città natale. -

20210514092607 Amarcorden

in collaborazione con: The main places linked to Fellini in Rimini Our location 12 31 Cimitero Monumentale Trento vialeTiberio 28 via Marecchia Matteotti viale Milano Venezia Torino 13 via Sinistra del Porto 27 Bologna Bastioni Settentrionali Genova Ravenna via Ducale via Destra del Porto Rimini Piacenza Firenze Ancona via Dario Campana Perugia Ferrara Circonvallazione Occidentale 1 Parma 26 Reggio Emilia viale Principe piazzale Modena via dei Mille dei via Amedeo Fellini Roma corso d’Augusto via Cavalieri via via L. Toninivia L. corso Giovanni XXIII Bari Bologna viale Valturio 14 Ravenna largo 11 piazza 19 21 Napoli Valturio Malatesta 15piazza piazza Cavour via GambalungaFerrari Forlì 3via Gambalunga Cesena via Cairoli 9 Cagliari Rimini via G. Bruno Catanzaro Repubblica di San Marino 2 7 20 22 Tintori lungomare Palermo via Sigismondo via Mentana Battisti Cesare piazzale i via Garibaldi via Saffi l a piazza Roma via n 5 o Tre Martiri 6 i 17 viaTempio Malatestiano d i via IV Novembre via Dante 23 r e 18 4 piazzale Covignano M via Clementini i Kennedy n o i t s a 16 B via Castelfidardo corso d’Augusto via Brighenti piazzale The main places linked to Fellini near Rimini 10 8 Gramsci via Roma Anfiteatro Arco e lungomare Murri lungomare l d’Augusto Bellaria a Bastioni Orientali n Igea Marina o Gambettola i viale Amerigo Vespucci Amerigo viale 33 d i r 25 e M e via S. Brancaleoni n o i z a l l a via Calatafimi Santarcangelo v n via XX Settembre o di Romagna c r piazza i 24 Ospedale 30Aeroporto viale Tripoli C Marvelli 32 Rimini via della Fiera viale Tripoli 29 Poggio Berni Rimini 18 Piazza Tre Martiri (formerly Piazza G.