The Inspirational Life of Robert Sengstacke Abbott by Bruce W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying African American Jeremiad Rhetoric As Culturally Competent Health Communication Online

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Summer 2019 Adding Soul to the Message: Applying African American Jeremiad Rhetoric as Culturally Competent Health Communication Online Wilbert Francisco LaVeist Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Health Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation LaVeist, Wilbert F.. "Adding Soul to the Message: Applying African American Jeremiad Rhetoric as Culturally Competent Health Communication Online" (2019). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/1h52-sr85 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/94 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADDING SOUL TO THE MESSAGE: APPLYING AFRICAN AMERICAN JEREMIAD RHETORIC AS CULTURALLY COMPETENT HEALTH COMMUNICATION ONLINE by Wilbert Francisco LaVeist B.A. May 1988, The Lincoln University of Pennsylvania M.A. December 1991, The University of Arizona A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY TECHNOLOGY AND MEDIA STUDIES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY AUGUST 2019 Approved by: Kevin A. Moberly Avi Santo Daniel P. Richards Alison R. Reed ABSTRACT ADDING SOUL TO THE MESSAGE: APPLYING AFRICAN AMERICAN JEREMIAD RHETORIC AS CULTURALLY COMPETENT HEALTH COMMUNICATION ONLINE Wilbert Francisco LaVeist Old Dominion University, 2019 Director: Dr. -

The Business Issue

VOL. 52, NO. 06 • NOVEMBER 24 - 30, 2016 Don't Miss the WI Bridge Trump Seeks Apology as ‘Hamilton’ Cast Challenges Pence - Hot Topics/Page 4 The BusinessCenter Section Issue NOVEMBER 2016 | VOL 2, ISSUE 10 Protests Continue Ahead of Trump Presidency By Stacy M. Brown cles published on Breitbart, the con- WI Senior Writer servative news website he oversaw, ABC News reported. The fallout for African Americans, President Barack Obama, the na- Muslims, Latinos and other mi- tion's first African-American presi- norities over the election of Donald dent, said Trump had "tapped into Trump as president has continued a troubling strain" in the country to with ongoing protests around the help him win the election, which has nation. led to unprecedented protests and Trump, the New York business- even a push led by some celebrities man who won more Electoral Col- to get the electorate to change its vote lege votes than Democrat Hillary when the official voting takes place on Clinton in the Nov. 8 election, has Dec. 19. managed to make matters worse by A Change.org petition, which has naming former Breitbart News chief now been signed by more than 4.3 Stephen Bannon as his chief strategist. million people, encourages members Bannon has been accused by many of the Electoral College to cast their critics of peddling or being complicit votes for Hillary Clinton when the 5 Imam Talib Shareef of Masjid Muhammad, The Nation's Mosque, stands with dozens of Christians, Jewish in white supremacy, anti-Semitism leaders and Muslims to address recent hate crimes and discrimination against Muslims during a news conference and sexism in interviews and in arti- TRUMP Page 30 before daily prayer on Friday, Nov. -

Impromptu Prompts

IMPROMPTU PROMPTS National Speech & Debate Association • updated 2/18/20 DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Impromptu Prompts ARTWORK ..................................................................................... 29 BOOK TITLES .................................................................................. 31 MOVIE TITLES ................................................................................ 29 OBJECTS ........................................................................................ 30 POLITICAL CARTOONS.................................................................... 30 PROMINENT FIGURES .................................................................... 31 QUOTATIONS ................................................................................ 31 Tournament Services: IMPROMPTU PROMPTS | National Speech & Debate Association • Prepared 2/18/20 - 2 - DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Impromptu Prompts – ARTWORK – Compiled in partnership with Wiley College and with the Sam Donaldson Center for Communication Studies Basketball Hoop Light Fixture – by David Hammons Lift Every Voice and Sing – by Augusta Savage Tournament Services: IMPROMPTU PROMPTS | National Speech & Debate Association • Prepared 2/18/20 - 3 - DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Migration Series – by Jacob Lawrence Harmonizing – by Horace Pippin Tournament Services: IMPROMPTU PROMPTS | National Speech & Debate Association • Prepared 2/18/20 - 4 - DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Trumpet – by Jean-Michel Basquiat The Emancipation Approximation – by Kara Walker Tournament Services: -

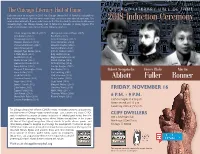

2018 Induction Ceremony Program

The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame CHICAGO LITERARY HALL OF FAME Each year since its inception in 2010, the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame has inducted our best historical writers. Until the most recent class, six writers were selected each year. The number was reduced to three in order to ensure that the standards for selection would remain 2018 Induction Ceremony incredibly high. Our Chicago Literary Hall of Fame now includes 45 literary figures. The induction ceremonies take place in the year following selection. Robert Sengstacke Abbott (2017) Alice Judson Ryerson Hayes (2015) Jane Addams (2012) Ben Hecht (2013) Nelson Algren (2010) Ernest Hemingway (2012) Margaret Anderson (2014) David Hernandez (2014) Sherwood Anderson (2012) Langston Hughes (2012) Rane Arroyo (2015) Fenton Johnson (2016) Margaret Ayer Barnes (2016) John H. Johnson (2013) L. Frank Baum (2013) Ring Lardner (2016) Saul Bellow (2010) Edgar Lee Masters (2014) Marita Bonner (2017) Harriet Monroe (2011) Gwendolyn Brooks (2010) Willard Motley (2014) Fanny Butcher (2016) Carolyn Rodgers (2012) Margaret T. Burroughs (2015) Mike Royko (2011) Cyrus Colter (2011) Carl Sandburg (2011) Robert Sengstacke Henry Blake Marita Floyd Dell (2015) Shel Silverstein (2014) Theodore Dreiser (2011) Upton Sinclair (2015) Abbott Fuller Bonner Roger Ebert (2016) Studs Terkel (2010) James T. Farrell (2012) Margaret Walker (2014) Edna Ferber (2013) Theodore Ward (2015) FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 16 Eugene Field (2016) Ida B. Wells (2011) Leon Forrest (2013) Thornton Wilder (2013) Henry Blake Fuller (2017) Richard Wright (2010) 6 P.M. - 9 P.M. Lorraine Hansberry (2010) Cash bar begins at 4:30 p.m. Dinner served at 6:15 p.m. -

Limitless Force Vol

, A BAHa` i ` COMPANION FOR YOUNG EXPLORERs www.brilliantstarmagazine.org VOL. 49 NO. 6 CLIMB THE STEPS Limitless TO SUCCESS ARE YOU SMART FORCE ABOUT SCREENS? super stadium animal hospital tt BAHÁ’Í NATIONAL CENTER 1233 Central Street, Evanston, Illinois 60201 U.S. 847.853.2354 [email protected] WHAT’S INSIDE Subscriptions: 1.800.999.9019 www.brilliantstarmagazine.org Published by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States FAVORITE FEATURES Amethel Parel-Sewell EDITOR/CREATIVE DIRECTOR C. Aaron Kreader DESIGNER/ILLUSTRATOR Bahá’u’lláh’s Life: Mission of Peace Amy Renshaw SENIOR EDITOR 4 Heidi Parsons ASSOCIATE EDITOR His Most Holy Book encourages spiritual growth. Katie Bishop ASSISTANT EDITOR Foad Ghorbani PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Lisa Blecker ARTIST & WRITER Nur’s Nook Donna Price WRITER 6 Make a cool wallet to stash your cash! Dr. Stephen Scotti STEM EDUCATION ADVISOR MANY THANKS TO OUR CONTRIBUTORS: Bera Abel • Shayda Alsalihi • Shayan Bavar • Destiney Riley’s Rainforest Brown • Rhett Butler • Eileen Collins • Elsie Davis • Bahia 8 How does cleanliness lift your spirit? Eady • Susan Engle • Layli Graham • Adib Julien • Darcy Malberg • Oisin Padilla Mc Loughlin • Paul Nurnberg Katrina Ostrom • Layli Phillips • Hugo Rash • Myiti Sengstacke-Rice • Kamil Shafizadeh • Victoria Smalls We Are One Bruce Whitmore • Nancy Wong • Christopher Zamani 11 Explore and care for the place we all call home. ART AND PHOTO CREDITS Illustrations by C. Aaron Kreader, unless noted By Lisa Blecker: Watercolor on pp. 13, 19; photos on pp. 6–7 Lightning and Luna: Episode #79 By Foad Ghorbani: Art on pp. 10, 12 14 Professor Prowd declares war on goodness. -

Residents Protest Board Vote That Ousted London Breed As Interim

VOL. LXXVV, NO. 49 • $1.00 + CA. Sales Tax THURSDAY, DECEMBERSEPTEMBER 12 17,- 18, 2015 2013 VOL. LXXXV NO 5 $1.00 +CA. Sales Tax“For Over “For Eighty Over Eighty Years YearsThe Voice The Voiceof Our of CommunityOur Community Speaking Speaking for forItself Itself” THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 1, 2018 is blindly support law en- forcement over the rights of its patrons and citi- zens, Metro CEO Phillip Washington has released a statement encouraging everyone from LAPD to the Metro riders to do what is right over what is popular and says “he is disappointed in the (LAPD) the situation es- calated”. On January 22, Bev- erly Nava said during a press conference that she sprained her wrist when FREDDIE ALLEN/AMG/NNPA an LAPD officer grabbed Rod Doss, the publisher of the New Pittsburgh her arm and pulled her off Courier, received the NNPA Publisher Lifetime the red line at the West- Achievement Award during the 2018 NNPA lake/MacArthur Park Sta- Mid-Winter Conference in Las Vegas, Nevada. tion for putting her foot on the back of a seat. BY STACY M. BROWN Publishers Association’s The incident which NNPA Newswire 2018 NNPA Publisher was caught on video Lifetime Achievement tape by a bystander has For 50 years, Rod Award at a ceremony in prompted LAPD to initi- Doss has remained dedi- Las Vegas. ate a use of force investi- cated to the New Pitts- “There is no greater Metro CEO Phil Washington PHOTO BY VALERIE GOODLOE FOR SENTINEL gation. burgh Courier and his honor than to be recog- Phil Washington who success has been among nized by your peers,” BY DANNY J. -

African American Media Today Building the Future from the Past

PUBLIC SQUARE PROGRAM The Obsidian Collection African American Media Today Building the Future From the Past BY ANGELA FORD, KEVIN MCFALL, BOB DABNEY | THE OBSIDIAN COLLECTION FEBRUARY 2019 STATE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN MEDIA: TAKEAWAYS • America’s Black press is made up of 158 publications across 29 states and D.C., with 20.1 million online readers. • The Black press was particularly hard hit by the loss of advertising revenue when tobacco companies pulled print advertising. • Building and maintaining archives can provide not only an important record of the history of the black press but also a template for strengthening the Black press today. Introduction Since its creation in the early 19th century, the Black press has played a crucial role in the broader journalism industry — reporting on relevant issues within the African-American community, shining a light on both its challenges and triumphs and providing a nuanced portrait of the lives of Black Americans when mainstream media would not. Today, Black legacy press faces many of the same struggles of the news industry overall, namely adapting to major losses of advertising revenue and an increasingly digital information landscape. Some legacy outlets are reimagining how they work and connect with their communities, while several young entrepreneurs of color are building digital-first organizations that tap into today’s news landscape. Both uniquely function to deliver news to Black audiences and tell the multitude of stories that exist in the Black community. As a journalism funder, Democracy Fund is dedicated to increasing the diversity of sources, stories, and staff in newsrooms. This includes supporting mainstream newsrooms as they work to better reflect the communities they serve, but also importantly, media that are both by and for diverse communities in the United States. -

I Am America: the Chicago Defender on Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali, and Civil Rights, 1934-1975

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-24-2014 12:00 AM I Am America: The Chicago Defender on Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali, and Civil Rights, 1934-1975 Nevada Cooke The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Nevada Cooke 2014 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, Nevada, "I Am America: The Chicago Defender on Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali, and Civil Rights, 1934-1975" (2014). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2027. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2027 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I AM AMERICA The Chicago Defender on Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali, and Civil Rights, 1934-1975 Thesis format: Monograph by Nevada Ross Cooke Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Nevada Cooke 2014 ABSTRACT This study examines the effect that the careers of Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali had on civil rights and race relations in the United States between 1934 and 1975 from the perspective of the black community, as interpreted through a qualitative analysis of the content provided by the Chicago Defender’s editorial posture and its black readership. -

Norman Mcrae Papers, Pt

Norman McRae Collection Papers, 1960s-1980s 29 linear feet 29 storage boxes Accession #337 DALNET # OCLC # Dr. Norman McRae was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1925 and received his B.A. in history and journalism, his teaching certificate, and his M.A. in education from Wayne State University. He taught social studies and developed and managed the federal personnel department in the Detroit Public Schools until 1967, leaving to join the Michigan-Ohio Regional Educational Laboratory and to accept an Urban Education Fellowship at The University of Michigan, where he subsequently obtained his Ph.D. He returned to the Detroit Public Schools in 1970, first as assistant director of teacher education and then as director of the social studies and fine arts departments, until his retirement in 1991. Since the mid-sixties, Dr. McRae has been an avid researcher and writer on African- American history, especially the history of Detroit’s African-American community; he played a major role in the development of multicultural and human rights curricula in the Detroit school system. In 1969 he taught the first black history course offered at Wayne State University. The Norman McRae collection consists primarily of a wide range of secondary source material — clippings, articles, pamphlets, studies, government publications — on African-American history and the African-American experience. Non-Manuscript Material: A few photographs of African-American military leaders have been placed in the Archives Audiovisual Collection. Important Subjects in the Collection: Africa African Americans and the Economy African-American Biography Black Power African-American Church Race Relations in the U.S. -

Today in Georgia History November 24, 1868 Robert Abbott Suggested

Today in Georgia History November 24, 1868 Robert Abbott Suggested Readings Christopher C. De Santis, ed., Langston Hughes and the Chicago Defender: Essays on Race, Politics, and Culture, 1942-62 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995). St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Cayton, Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City, rev. and enl. ed. (1945; reprint, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993). James R. Grossman, Land of Hope: Chicago, Black Southerners, and the Great Migration (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989). Roi Ottley, The Lonely Warrior: The Life and Times of Robert S. Abbott (Chicago: H. Regnery Co., 1955). Patrick S. Washburn, A Question of Sedition: The Federal Government's Investigation of the Black Press during World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986). “Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1868-1940).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-3196&sug=y The Chicago Defender: http://www.chicagodefender.com/ African-American Registry: http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/robert-abbott- founder-chicago-defender Newspaper article about marker dedication: http://savannahnow.com/intown/2008-08-26/marker- honors-local-publishing-giant#.TrmnE3I1Rf0 Image Credits November 24, 1868: Robert Abbott Black Children Playing in Black-Belt Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF33-005164-M5 Black Grocer in Black-Belt Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF33-005142-M2 Black owned Diner, The Perfect Eat Shop Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USW3-001469-D Abbott, Robert S. “A Recapitulation of 25 Year Work”. Chicago Defender. May 3, 1930: A1. -

Introduction

Introduction Each decade of the twentieth century is closely iden- tant works of literature, films and other cultural indi- tified with at least one landmark or major turning cators that were part of the 1910s. point. In the 1910s, two major things stand out— Controversy is sure to abound in any work that dis- World War I (1914-1918) and the Progressive Era cusses American history and the 1910s is no excep- (approximately 1895-1921). tion. The Jim Crow system, now called racial segrega- Coverage in this work of World War I focuses on tion, is a good example. Today, most Americans American involvement, how and why the U.S. de- understand this social system as unjust, and sympa- clared war on Germany in 1917, the sinking of the thize with the National Association for the Advance- Lusitania, U.S. bias against Germany, the Zimmer- ment of Colored People in opposing that system. mann telegram, Germany’s declaration of unre- The articles in this work that deal with Jim Crow at- stricted submarine warfare and so much more. No tempt to present the facts of what the system was like, study of the war could ignore the major U.S. battles, not to condemn or condone. such as the Meuse-Argonne offensive, individuals A controversial movie of the decade was The Birth such as Woodrow Wilson, General John J. Pershing, of a Nation, directed by David W. Griffith in 1915. The and Sergeants Alvin York, events such as govern- movie takes place in the South following the Civil mental regulations of the economy at the home War, portraying African Americans generally as igno- front, the Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of rant and violent, and showed members of the Ku Versailles. -

Professor Myiti Sengstacke-Rice - BIO

Professor Myiti Sengstacke-Rice - BIO Myiti Sengstacke-Rice Ma.Ed is the President and CEO of the Chicago Defender Charities which produces the 90 year-old Bud Billiken Parade and Festival. She is also the Founder and Publisher of Bronzeville Life, a lifestyle publication inspired by the historic arts, culture, news and politics of the rich historical community and Chicago land. She is the author of Chicago Defender, a volume in the “Images of America Series” published by Arcadia Publishing. The book captures its sweeping imprint on twentieth century African American culture and American History. She is also a contributing author to Building the Black Metropolis: African American Entrepreneurship in Chicago (New Black Studies Series). Sengstacke-Rice carved out a unique voice as a living link to the years of Chicago’s history, which her father, grandfather and great granduncle helped make possible. Her father is renowned photographer, Bobby Sengstacke; her grandfather, John H. Sengstacke is the late publisher of the Chicago Defender and prominent civil rights advocate and critical negotiator for the White House. Finally, her great granduncle was Robert Sengstacke Abbott, the founding publisher of the Chicago Defender and the Bud Billiken Parade. Following the footsteps of Abbott and her grandfather, Sengstacke-Rice attended Hampton University in Virginia. Growing up around media and publishing Myiti also had a passion for journalism beginning her career as a reporter for the Chicago Defender after attending her undergraduate studies at Hampton. She later became Associate Editor of the Chicago Defender. Sengstacke-Rice has been featured in several magazine publications and television appearances such as Black Enterprise, Essence, Wall Street Journal, New York Times and CNN to name a few.