What Nancy Knew, What Carol Knew: Mass Literature and Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applying African American Jeremiad Rhetoric As Culturally Competent Health Communication Online

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons English Theses & Dissertations English Summer 2019 Adding Soul to the Message: Applying African American Jeremiad Rhetoric as Culturally Competent Health Communication Online Wilbert Francisco LaVeist Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Health Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation LaVeist, Wilbert F.. "Adding Soul to the Message: Applying African American Jeremiad Rhetoric as Culturally Competent Health Communication Online" (2019). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, English, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/1h52-sr85 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/english_etds/94 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADDING SOUL TO THE MESSAGE: APPLYING AFRICAN AMERICAN JEREMIAD RHETORIC AS CULTURALLY COMPETENT HEALTH COMMUNICATION ONLINE by Wilbert Francisco LaVeist B.A. May 1988, The Lincoln University of Pennsylvania M.A. December 1991, The University of Arizona A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY TECHNOLOGY AND MEDIA STUDIES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY AUGUST 2019 Approved by: Kevin A. Moberly Avi Santo Daniel P. Richards Alison R. Reed ABSTRACT ADDING SOUL TO THE MESSAGE: APPLYING AFRICAN AMERICAN JEREMIAD RHETORIC AS CULTURALLY COMPETENT HEALTH COMMUNICATION ONLINE Wilbert Francisco LaVeist Old Dominion University, 2019 Director: Dr. -

Outwitting the Devil) Napoleon Hill

" FEAR is the tool of a man-made devil. Self-confident faith in one's self is both the man-made weapon which defeats this devil and the man-made tool which builds a triumphant life. And it is more than that. It is a link to the irresistible forces of the universe which stand behind a man who does not believe in failure and defeat as being anything but temporary experiences." -NAPOLEON HILL Praise/or Napoleon Hill's OUTWITTING THE DEVIL "Outwitting the Devil proves once again that the messages and philoso phies of Napoleon Hill are timeless. This book contains insights on how to break free of habits and attitudes that prevent success and will ultimately lead to happiness and prosperity. If you want to break through your own roadblocks, read this book!" - T. HARV EKER, author of#l New York Times best seller Secrets ofthe Millionaire Mind "If you want to own your life, you have to own your money. In Outwitting the Devil) Napoleon Hill shares what may be holding you back in your financial life and charts the course for you to take control and own the life of your dreams." -JEAN CHATZKY, financial journalist and aurhor of The Difference: How Anyone Can Prosper in Even the Toughest Times "I have probably studied Napoleon Hill's work as much as anyone alive. It was 50 years ago that I picked up Think and Grow Rich. I have it with me all the time and read it every day. When Sharon Lechter sent me a copy of Outwitting the Devil I thought Hill has done it again, another world changer. -

The Business Issue

VOL. 52, NO. 06 • NOVEMBER 24 - 30, 2016 Don't Miss the WI Bridge Trump Seeks Apology as ‘Hamilton’ Cast Challenges Pence - Hot Topics/Page 4 The BusinessCenter Section Issue NOVEMBER 2016 | VOL 2, ISSUE 10 Protests Continue Ahead of Trump Presidency By Stacy M. Brown cles published on Breitbart, the con- WI Senior Writer servative news website he oversaw, ABC News reported. The fallout for African Americans, President Barack Obama, the na- Muslims, Latinos and other mi- tion's first African-American presi- norities over the election of Donald dent, said Trump had "tapped into Trump as president has continued a troubling strain" in the country to with ongoing protests around the help him win the election, which has nation. led to unprecedented protests and Trump, the New York business- even a push led by some celebrities man who won more Electoral Col- to get the electorate to change its vote lege votes than Democrat Hillary when the official voting takes place on Clinton in the Nov. 8 election, has Dec. 19. managed to make matters worse by A Change.org petition, which has naming former Breitbart News chief now been signed by more than 4.3 Stephen Bannon as his chief strategist. million people, encourages members Bannon has been accused by many of the Electoral College to cast their critics of peddling or being complicit votes for Hillary Clinton when the 5 Imam Talib Shareef of Masjid Muhammad, The Nation's Mosque, stands with dozens of Christians, Jewish in white supremacy, anti-Semitism leaders and Muslims to address recent hate crimes and discrimination against Muslims during a news conference and sexism in interviews and in arti- TRUMP Page 30 before daily prayer on Friday, Nov. -

Think and Grow Rich

THINK AND GROW RICH by Napoleon Hill NAPOLEON HILL THINK AND GROW RICH TABLE OF CONTENTS Author’s Preface ...................................................................................................................... p. 3 Chapter 1 — Introduction ....................................................................................................... p. 9 Chapter 2 — Desire: The Turning Point of All Achievement ................................................. p. 22 Chapter 3 — Faith Visualization of, and Belief in Attainment of Desire ............................... p. 40 Chapter 4 — Auto-Suggestion the Medium for Influencing the Subconscious Mind .............. p. 58 Chapter 5 — Specialized Knowledge, Personal Experiences or Observations ...................... p. 64 Chapter 6 — Imagination: the Workshop of the Mind .......................................................... p. 77 Chapter 7 — Organized Planning, the Crystallization of Desire into Action ........................ p. 90 Chapter 8 — Decision: the Mastery of Procrastination ......................................................... p. 128 Chapter 9 — Persistence: the Sustained Effort Necessary to Induce Faith ........................... p. 138 Chapter 10 — Power of the Master Mind: the Driving Force ................................................. p. 153 Chapter 11 — The Mystery of Sex Transmutation .................................................................. p. 160 Chapter 12 — The Subconscious Mind: The Connecting Link .............................................. -

NAPOLEON HILL Principle 1: Definite Major Purpose

NAPOLEON HILL Principle 1: Definite Major Purpose The Value of Goals His success has come from setting them, reaching them and setting them again. Bill Lee is a handsome, personable, energetic man of 48 who set his goal to be worth a million dollars by age 40. He achieved his goal at 39. Today he is rich by most people's standards. And he has good things to say about money. The thing that's beautiful about wealth is that it offers you so many more options in life," he says. "If you're generous, you can be more so. If you have strong social values, you can support projects that help other people and your community." He believes that almost anyone can stop being a "slave" and can gain financial independence by learning to set goals. As a management consultant and teacher extraordinaire, he emphasizes this point in seminars and conferences all over the country, as well as in his national newsletter for the builders supply industry, People and Profit$. Lee, a Georgia native, graduated from Emory University in Atlanta with a degree in psychology. He got a taste for teaching entrepreneurship on his first job out of college, working for Atlanta Newspapers, Inc. His office taught young carriers the principles of free enterprise and trained them to keep their buying, selling and collecting records accurately and to deliver the best possible service to the customers of the Atlanta Journal. Looking for Success: Also during that time he was introduced by a friend to a dynamic seminar speaker who stressed the power of setting goals for success in life. -

A Plume Book Grow Rich! with Peace of Mind

Grow Rich With Peace of Mind – Napoleon Hill A PLUME BOOK GROW RICH! WITH PEACE OF MIND NAPOLEON HILL was born into poverty in 1883, and achieved great success as an attorney and journalist. He was an advisor to Andrew Carnegie and Franklin Roosevelt. With Carnegie's help, he formulated a philosophy of success, drawing on the thoughts and experiences of a multitude of rags-to-riches tycoons. In recent years, the Napoleon Hill Foundation has published his bestselling writings worldwide, giving him an immense influence around the globe. Among his famous titles are Think and Grow Rich Action Pack, Napoleon Hill's A Year of Growing Rich, and Napoleon Hill's Keys to Success. Law of Attraction Haven Grow Rich With Peace of Mind – Napoleon Hill GROW RICH! WITH PEACE OF MIND Napoleon Hill A PLUME BOOK Law of Attraction Haven Grow Rich With Peace of Mind – Napoleon Hill Preface Napoleon Hill as a youth was no different from most young people today. He associated success with money in his early career. He wanted to be important, with a display of opulence. People today tend to associate the popular book Think and Grow Rich in terms of money - but Hill's perspective was to change as he matured. Hill remarked in one of his papers that during his early career when he was receiving large sums of money, he believed it essential that he drive nothing less than a Rolls Royce. He purchased a large estate in New York; he had servants and a variety of other employees to tend to his wants. -

Napoleon Hill's Golden Rules

th elost writings FM_1 11/15/2008 4 FM_1 11/15/2008 1 NAPOLEON HILL’S GOLDEN RULES NAPOLEON HILL Downloaded from www.lifebooks4all.blogspot.com John Wiley & Sons, Inc. FM_1 11/15/2008 2 Copyright # 2009 by The Napoleon Hill Foundation. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646- 8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http:// www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

THE LAW of SUCCESS Lesson Six IMAGINATION

TTHHEE LLAAWW OOFF SSUUCCCCEESSSS IN SIXTEEN LESSONS Teaching, for the First Time in the History of the World, the True Philos- ophy upon which all Personal Success is Built. BY NAPOLEON HILL 1 9 2 8 PUBLISHED BY The RALSTON UNIVERSITY PRESS MERIDEN, CONN. Ebook version ©Minding the Future Ltd, 2003, All Rights Reserved COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY NAPOLEON HILL ______ All Rights Reserved Ebook version ©Minding the Future Ltd, 2003 All Rights Reserved Printed in the U.S.A. - 2 - Lesson Six IMAGINATION - 3 - I CALL THAT MAN IDLE WHO MIGHT BE BET- TER EMPLOYED. - Socrates - 4 - THE LAW OF SUCCESS Lesson Six IMAGINATION "You Can Do It if You Believe You Can!” IMAGINATION is the workshop of the human mind wherein old ideas and established facts may be reassembled into new combinations and put to new uses. The modern dictionary defines imagination as follows: "The act of constructive intellect in grouping the materials of knowledge or thought into new, original and rational systems; the constructive or creative faculty; embracing poetic, artistic, philosophic, scientific and ethical imagination. "The picturing power of the mind; the formation of mental images, pictures, or mental representation of objects or ideas, particularly of objects of sense perception and of mathematical reasoning! also the reproduction and combination, usually with more or less irrational or abnormal modification, of the images or ideas of memory or recalled facts of experience." Imagination has been called the creative power of the soul, but this is somewhat abstract and goes more deeply into the meaning than is necessary from the - 5 - viewpoint of a student of this course who wishes to use the course only as a means of attaining material or monetary advantages in life. -

OTD Secretchptr.Pdf

• The Secret Chapter • Introduction Thank you for visiting outwittingthedevil.com. I was honored to be asked to edit and annotate Napoleon Hill’s manuscript. In doing so, this Secret Chapter was taken out of the final book because it was a story in its own right that validates Hill’s philosophy on the power of his Mastermind principle. As he shares his story about an Interview with his invisible counselors, you will understand the importance of studying the wisdom of the greatest minds of history. One of Napoleon Hill’s greatest gifts is sharing with us the power of collective wisdom. Alone, we must work long hours and struggle to create success. Together we can speed our way to success by drawing on the strengths of each individual participant. In Outwitting the Devil Hill reveals his interview with the Devil and he leaves it to the reader to determine if he was talking to the real devil or an imaginary devil. The brilliance of his manuscript is found in his ability to reveal and expose the self-limiting beliefs which may be preventing each of us from achieving the success we so richly deserve. He shares his own battles with the Devil and times in his life when he was in the depths of despair and depression and how he found his way to success by following the very same principles he shares in Think and Grow Rich and Outwitting the Devil . Please enjoy the Secret Chapter, but don’t miss out on reading Outwitting the Devil . Here are some of the reviews it is receiving from around the world: NAPOLEON HILL “If widely read this book could trigger a seismic shift in positive outcomes” – SAM333 (BarnesandNoble.com) “Don't let this one get away! I'm going to recommend Outwitting the Devil to everyone I care about! I suggest you do the same - and start with yourself.” – GCONRAD (Barnesandnoble.com) “We are all working to ‘outwit the devil’ as we struggle to be the best we can be. -

Impromptu Prompts

IMPROMPTU PROMPTS National Speech & Debate Association • updated 2/18/20 DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Impromptu Prompts ARTWORK ..................................................................................... 29 BOOK TITLES .................................................................................. 31 MOVIE TITLES ................................................................................ 29 OBJECTS ........................................................................................ 30 POLITICAL CARTOONS.................................................................... 30 PROMINENT FIGURES .................................................................... 31 QUOTATIONS ................................................................................ 31 Tournament Services: IMPROMPTU PROMPTS | National Speech & Debate Association • Prepared 2/18/20 - 2 - DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Impromptu Prompts – ARTWORK – Compiled in partnership with Wiley College and with the Sam Donaldson Center for Communication Studies Basketball Hoop Light Fixture – by David Hammons Lift Every Voice and Sing – by Augusta Savage Tournament Services: IMPROMPTU PROMPTS | National Speech & Debate Association • Prepared 2/18/20 - 3 - DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Migration Series – by Jacob Lawrence Harmonizing – by Horace Pippin Tournament Services: IMPROMPTU PROMPTS | National Speech & Debate Association • Prepared 2/18/20 - 4 - DIVER SITY AND INCLUSION Trumpet – by Jean-Michel Basquiat The Emancipation Approximation – by Kara Walker Tournament Services: -

THE MAGIC LADDER to SUCCESS by Napoleon Hill Author of the “Law of Success” a More Extensive Work in Eight Volumes

AUTHOR OF “THINK AND GROW RICH” An Official Publication of the NAPOLEON HILL FOUNDATION Napoleon Hill I fear nothing except the earthly “hell” called poverty. I am devoting my life to helping millions of people to conquer this foe. THE MAGIC LADDER TO SUCCESS by Napoleon Hill Author of the “Law of Success” A more extensive work in eight volumes INTERNATIONAL SUCCESS UNIVERSITY International Building WASHINGTON, D.C. TO CLAIM YOUR ADDITIONAL FREE RESOURCES PLEASE VISIT SOUNDWISDOM.COM/NAPHILL © Copyright 2018—The Napoleon Hill Foundation Original Edition Copyright 1930 Napoleon Hill All rights reserved. This book is protected by the copyright laws of the United States of America. This book may not be copied or reprinted for commercial gain or profit. The use of short quotations or occasional page copying for personal or group study is permitted and encouraged. Permission will be granted upon request. For permissions requests, write to the publisher, addressed “Attention: Permissions Coordinator,” at the address below. SOUND WISDOM P.O. Box 310 Shippensburg, PA 17257-0310 For more information on publishing and distribution rights, call 717-530-2122 or info@ soundwisdom.com Quantity Sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, and others. For details, contact the Sales Department at Sound Wisdom. International rights inquiries please contact The Napoleon Hill Foundation at 276-328- 6700 or email [email protected] Reach us on the Internet: www.soundwisdom.com. ISBN HC: 978-1-64095-055-9 ISBN TP: 978-1-64095-068-9 ISBN Ebook: 978-1-64095-056-6 For Worldwide Distribution, Printed in the U.S.A. -

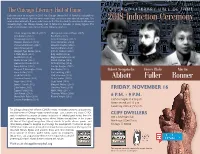

2018 Induction Ceremony Program

The Chicago Literary Hall of Fame CHICAGO LITERARY HALL OF FAME Each year since its inception in 2010, the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame has inducted our best historical writers. Until the most recent class, six writers were selected each year. The number was reduced to three in order to ensure that the standards for selection would remain 2018 Induction Ceremony incredibly high. Our Chicago Literary Hall of Fame now includes 45 literary figures. The induction ceremonies take place in the year following selection. Robert Sengstacke Abbott (2017) Alice Judson Ryerson Hayes (2015) Jane Addams (2012) Ben Hecht (2013) Nelson Algren (2010) Ernest Hemingway (2012) Margaret Anderson (2014) David Hernandez (2014) Sherwood Anderson (2012) Langston Hughes (2012) Rane Arroyo (2015) Fenton Johnson (2016) Margaret Ayer Barnes (2016) John H. Johnson (2013) L. Frank Baum (2013) Ring Lardner (2016) Saul Bellow (2010) Edgar Lee Masters (2014) Marita Bonner (2017) Harriet Monroe (2011) Gwendolyn Brooks (2010) Willard Motley (2014) Fanny Butcher (2016) Carolyn Rodgers (2012) Margaret T. Burroughs (2015) Mike Royko (2011) Cyrus Colter (2011) Carl Sandburg (2011) Robert Sengstacke Henry Blake Marita Floyd Dell (2015) Shel Silverstein (2014) Theodore Dreiser (2011) Upton Sinclair (2015) Abbott Fuller Bonner Roger Ebert (2016) Studs Terkel (2010) James T. Farrell (2012) Margaret Walker (2014) Edna Ferber (2013) Theodore Ward (2015) FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 16 Eugene Field (2016) Ida B. Wells (2011) Leon Forrest (2013) Thornton Wilder (2013) Henry Blake Fuller (2017) Richard Wright (2010) 6 P.M. - 9 P.M. Lorraine Hansberry (2010) Cash bar begins at 4:30 p.m. Dinner served at 6:15 p.m.