Newsletter 4--November 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Julius Hirsch Nationalspieler - Ermordet Aber Nicht Vergessen!

in Gedenken an Julius Hirsch Nationalspieler - ermordet aber nicht vergessen! Mannschaftsbild des KFV 1910, stehend von links: Hüber, Burger, Tscherter, Ruzek, Breunig, Hollstein, Bosch, Gros. Sitzend von links: Förderer, Schwarze, Hirsch, Fuchs, Kächele. Julius Hirsch – 07.04.1892 - 08.05.1945 (für tot erklärt ) Julius Hirsch ist als jüngster Sohn, als eines von insgesamt sieben Kindern in Achern auf die Welt gekommen. Mit 6 Jahren wurde er in Karlsruhe eingeschult und beende- te seine Schulzeit mit der mittleren Reife. Daraufhin besuchte er eine Handelsschule und machte eine Lehre als Kaufmann bei der Karlsruher Lederhandlung Freund und Strauss. Dort arbeitete er bis zum 22.03.1912. Hirsch mit Förderer und Fuchs auf dem Cover von „Süddeutscher Julius Hirsch auf dem Cover von „Fußball“, 1922. Illustrierter Sport“, 1921. Ab dem 07.08.1914 diente er als Soldat im Ersten Weltkrieg und erreichte innerhalb von vier Dienstjahren den Rang des Vizefeldwebels und wurde mit dem Eisernen Kreuz II. Klasse ausgezeichnet. Nach dem Krieg arbeitete er bei der Nürnberger Bing AG und kehrte erst danach zum 01.04.1919 zurück nach Karlsruhe in die Deutsche Signalflaggenfabrik seines Vaters. 1920 heiratete er die gebürtige Karlsruherin Ella Karolina Hauser und bekam 1922 und 1928 die Kinder Heinold Leopold und Esther Carmen. 1926 bekamen Julius und sein Bruder Max die Geschäftsanteile des Vaters an dem Unternehmen. Allerdings wurde am 10.02.1933 das Konkursverfahren über das Un- ternehmen eröffnet und jenes liquidiert, wegen einer Bürgschaft die Max Hirsch ge- geben hatte. Der nun nach Arbeit suchende Hirsch ging in die Schweiz und anschließend in den Elsass und trat dort eine Trainerstelle bei der F.A. -

Information Issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain • Fairfax Mansions

Vol. XVII No. 7 July, 1962 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN • FAIRFAX MANSIONS. FINCHLEY RD. (corner Fairfax Rd.). London. N.W.I Offset and ConMuUiitg Hours: Telephone: MAIda Vale 9096/7 (General OIkce and Welfare tor tha Aged) Moi\day to Thursday 10 a.in.—I p.m. 3—6 p.m MAIda Vale 4449 (Employment Agency, annually licensed bv the L.C.C,, and Social Services Dept.) Friday 10 ajn.—l p.m. Ernst Kahn Austrian baroque civilisation, tried to cope with their situation. Schnitzler, more fortunate than Weininger, if only through his exterior circum stances, knew much about the psychological struc THE YOUNG GENERATION CARRIES ON ture of Viennese middle-class s(Kiety and Jewry. The twilight, uncertainly and loneliness of the human soul attracted him, but his erotism is half- Sixth Year Book of the Leo Baeck Institute playful, half-sorrowful and does not deceive him about the truth that ". to write means to sit Those amongst us who remember our German- To some extent these achievements were due to in judgment over one's self". It enabled him to Jewish past are bound to wonder who will carry the Rabbi's charm which attracted Polish Jews objectivise the inner struggles of Jews who sought On with the elucidation of the relevant problems and German high-ranking officers and aristocrats the " Way into the Open ", i.e., into assimilation in once the older witnesses are no longer available. alike with whom he collaborated very closely. its different forms. The Year Book 1961* brings this home to us by This went so far that the German officials called Weininger. -

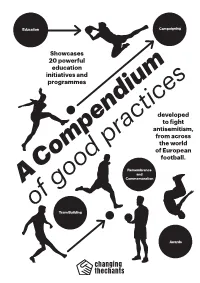

A Compendium of Good Practices

1 Education Campaigning Showcases 20 powerful education initiatives and programmes developed to fight antisemitism, from across the world of European football. CompendiumRemembrance and A Commemoration of good practices Team Building Awards 2 What are you reading ? This Compendium of good practices showcases 20 power- ful education initiatives and programmes, developed to fight antisemitism, from across the world of European football. The Compendium is not the definitive list of all noteworthy initiatives, nor is it an evaluation of a selection of programmes which are considered to be the best which exist; its aim is, rather, to highlight some of the existing practices - from workshops to commemoration plaques and remembrance trips to online campaigns – in the hope they might spark interest and motivate clubs, associations, fan groups and other stakeholders within or associated with the football community to develop their own practices. The initiatives were selected as a result of research conducted by a group of eight researchers and experts from across Europe who were all part of the Changing the Chants project. They conducted desk research and interviewed stake- holders connected to these initiatives. As a result, for every initiative the Compendium provides project background and context and an overview of what took place. Due to the limited scope of this Compendium, it has not been possible to analyse all these good practices in great depth and, as such, readers of this Compendium are invited and encouraged to seek out further information where further detail has not been provided. Categorization The practices have been categorised against five overarching themes: Campaigning (1), Education (2), Remembrance and com- memoration (3), Network building (4) and Awards (5). -

Whole Dissertation Hajkova 3

Abstract This dissertation explores the prisoner society in Terezín (Theresienstadt) ghetto, a transit ghetto in the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia. Nazis deported here over 140, 000 Czech, German, Austrian, Dutch, Danish, Slovak, and Hungarian Jews. It was the only ghetto to last until the end of Second World War. A microhistorical approach reveals the dynamics of the inmate community, shedding light on broader issues of ethnicity, stratification, gender, and the political dimension of the “little people” shortly before they were killed. Rather than relegating Terezín to a footnote in narratives of the Holocaust or the Second World War, my work connects it to Central European, gender, and modern Jewish histories. A history of victims but also a study of an enforced Central European society in extremis, instead of defining them by the view of the perpetrators, this dissertation studies Terezín as an autarkic society. This approach is possible because the SS largely kept out of the ghetto. Terezín represents the largest sustained transnational encounter in the history of Central Europe, albeit an enforced one. Although the Nazis deported all the inmates on the basis of their alleged Jewishness, Terezín did not produce a common sense of Jewishness: the inmates were shaped by the countries they had considered home. Ethnicity defined culturally was a particularly salient means of differentiation. The dynamics connected to ethnic categorization and class formation allow a deeper understanding of cultural and national processes in Central and Western Europe in the twentieth century. The society in Terezín was simultaneously interconnected and stratified. There were no stark contradictions between the wealthy and majority of extremely poor prisoners. -

They Helped Modernize Turkey's Medical Education and Practice

Gesnerus 65 (2008) 56–85 They Helped Modernize Turkey’s Medical Education and Practice: Refugees from Nazism 1933–1945* Arnold Reisman Summary This paper discusses a dimly lit and largely unknown bit of 20th century history. Starting in 1933, Turkey reformed its medical health care system using invitees fleeing the Nazis and for whom America was out of reach because of restrictive immigration laws and wide-spread anti-Semitic hiring bias at its universities. Among the invitees were several medical scholars who played a large role in westernizing the new Turkish republic’s medical practice and research as well as its school curricula. Keywords: Jewish doctors under Nazism; history of medicine in Turkey; medical education Introduction Starting in 1933, the Nazis’ plan to rid themselves of Jews beginning with intellectuals with Jewish roots or spouses became a windfall for Ataturk’s determination to modernize Turkey. A select group of Germans with a record of leading-edge contributions to their respective disciplines was invited with Reichstag’s backing to transform Turkey’s higher education and the new Turkish state’s entire infrastructure. This arrangement, occurring before the activation of death camps, served the Nazis’ aim of making their universities, professions, and their arts judenrein, cleansed of Jewish influence and free from intelligentsia opposed to fascism. Because the Turks needed the help, Germany could use it as an exploitable chit on issues of Turkey’s neutrality * This paper is based on Arnold Reisman, Turkey’s Modernization: Refugees from Nazism and Ataturk’s Vision, New Academia Publishers (Washington DC 2006). Arnold Reisman, PhD, PE, 18428 Parkland Drive, Shaker Heights, Ohio 44122, USA ([email protected]). -

Julius Hirsch. Nationalspieler 2012-3-115 Skrentny, Werner

W. Skrentny: Julius Hirsch. Nationalspieler 2012-3-115 Skrentny, Werner: Julius Hirsch. Nationalspieler. und seiner Brüder Frontkämpfereinsatz sowie Ermordet. Biografie eines jüdischen Fußballers. an zahllose andere „national denkende und Göttingen: Verlag Die Werkstatt 2012. ISBN: auch durch die ‚Tat bewiesene und durch das 978-3-89533-858-8; 352 S. Herzblut vergossene‘ (sic) deutsche Juden“ (S. 163). Trotz des um sich greifenden Anti- Rezensiert von: Markwart Herzog, Schwa- semitismus und des Ausschlusses jüdischer benakademie Irsee Turner und Sportler aus den Vereinen wollte der KFV, was in der Forschung oft übersehen Über Julius Hirsch erschienen bereits zwei wurde, die Austrittserklärung nicht akzeptie- Biografien, in denen die meisten wichti- ren und bedauerte sie. Für den vaterländisch gen Daten aus dem Leben des jüdischen gesonnenen Juden Hirsch war es folgerichtig, Fußballspielers dokumentiert sind.1 Hirschs sich nach dem Austritt keinem Verein der zio- Karriere ist untrennbar mit dem Karlsruher nistischen Sportorganisation Makkabi anzu- Fußballverein (KFV) der Kaiserzeit verbun- schließen, sondern 1934 dem jüdischen Turn- den. Auch zur „Fußballhochburg Karlsru- club Karlsruhe 03 (TCK), der im Sportbund he“ konnte Werner Skrentny auf frühere For- Schild des ultranationalen Reichsbundes jüdi- schungen zurückgreifen.2 Dennoch gelingt es scher Frontsoldaten organisiert war, als Spie- seiner Biografie, neue Details über Karriere ler und Trainer beizutreten. Mit dem TCK ge- und Schicksal Hirschs zu recherchieren und wann Hirsch 1936 die Badische Meisterschaft mit einer ebenso ausführlichen wie spannen- des Sportbundes Schild. den Analyse der Rezeption des Spieleridols Julius Hirsch war im Tuchhandel, in der der Kaiserzeit in den Medien der Jahre vor Herstellung und dem Vertrieb von Flaggen, und nach 1945 abzurunden. -

The Cup and the Sword Imploding Empire Trevor Phillips P 16

AJ R Info rma tion Volume UII No. 8 August 1998 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss ... AGM report Reflections on the link between soccer violence and politics Ronald Channing P3 Walter Benjamin and Judaism jane Edwards p 13 The Cup and the sword Imploding Empire Trevor Phillips p 16 Re-run of 1936? orld Cup football is - to coin a mixed made good its human and material losses from Hit n Ancient Greece metaphor - a double-edged sword. On ler's war, Nazism holds a marginal attraction. It the Olympics W one hand it intermingles multitudes in feeds on the populi.st desire for a man in uniform I provided cherished goodnatured rivalry; on the other it provides an whose sword will cut through the Gordian knot of periods of peace outlet for bloodcurdling xenophobia. This year the contemporary problems. amid warring city first di.scordant note was struck by English soccer Like German Francophobia, Ru.ssian power wor states. The modern hooligans. Drunk, destructive and sporting Cross of ship has deep historical roots. The Tsar gloried in Olympics were St George tattoos, they reminded the French that 'if the tide of autocrat - which is a pejorative term in meant to serve the it wasn't for us Engli.sh you'd be krauts. the We.st - and was venerated as such by the Ortho pacific ideal Apart from inculcating history lessons, their main dox Church. (By coincidence, the Russian-Orthodox worldwide - yet aiin, however, was simply to wreak havoc for its Church has recently resorted to the Nazi practice of the 1936 Games own sake. -

Verlorene Helden

IN ZUSAMMENARBEIT MIT DER DFB-KULTURSTIFTUNG VERLORENE HELDEN VON GOTTFRIED F UCH S BIS WALTH ER BENSEMANN — D IE VERTREIBUNG DER JUDEN AUS DEM DEUTSCH EN FU SSBALL NACH 1933 BÜCHER 3 11 FREUNDE VERLORENE HELDEN EDITORIAL gegen das Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, als der 13 Jahre alte Leo Weinstein im Frühjahr 1934 zum Training der Nachwuchs- Vergessen mannschaft des SV Werder Bremen kam, erlebte er den Schock seines jungen Lebens. Der Trainer teilte dem schon seit fünf Jahren im Klub aktiven Jungen mit, dass er ab sofort nicht mehr mitspielen dürfe: weil er Jude sei. Ausgrenzungen solcher Art erlebten in Deutschland ab dem Frühjahr 1933 Ronny Blaschke Wie Neonazis den Fußball L. Peiffer / D. Schulze-Marmeling (Hrsg.) tausende jüdische Spieler, Trainer, Schiedsrichter, Funktionäre, Mäzene oder Angriff von Rechtsaußen missbrauchen: Ein hoch aktuelles, Hakenkreuz und rundes Leder 224 S., Paperback, Fotos »immens wichtiges Buch« 608 S., Hardcover, Fotos einfache Mitglieder. Dabei hatten viele von ihnen sich in ihren Klubs über viele ISBN 978-3-89533-771-0 (11Freunde). ISBN 978-3-89533-598-3 € 16,90 (E-Book: 12,99) € 39,90 Jahre engagiert, hatten mitgeholfen, Deutsche Meisterschaften zu gewinnen, Der Autor wurde ausgezeichnet mit dem Julius-Hirsch-Ehrenpreis des DFB 2013. »Umfassende Analyse« (FAZ) namhafter Sporthistoriker zum waren Nationalspieler oder sogar Gründungsmitglieder großer Vereine wie dem Fußball im Nationalsozialismus: Täter, Opfer, Mitläufer. FC Bayern München, Eintracht Frankfurt oder dem 1. FC Nürnberg gewesen. Die Vertreibung der Juden aus dem Sport ist die Geschichte eines großen Verlus- tes, der jahrzehntelang fast vergessen gewesen ist. Das hat sich in den letzten Fußballbuch des 15 Jahren durch engagierte Forscher und Fan-Initiativen glücklicherweise allmäh- Jahres 2011 lich geändert. -

December 9, 2020 Chelsea FC Launch Exhibition About Jewish Athletes

December 9, 2020 Chelsea FC launch exhibition about Jewish Athletes and the Holocaust Chelsea Football Club, in partnership with Jewish News and renowned British Israeli street artist Solomon Souza, are today launching the exhibition “49 Flames - Jewish Athletes and the Holocaust”. Last year, Chelsea FC and club owner Roman Abramovich commissioned Solomon Souza to create a commemorative mural oF Jewish Football players who perished during the Holocaust. The Final piece was presented during an event at StamFord Bridge observing Holocaust Memorial Day 2020. The Club have now worked with Souza to develop an extended exhibition Featuring Jewish athletes who were killed by the Nazis during the Second World War. The art installation and virtual exhibition is part oF Chelsea FC’s Say No to Antisemitism campaign and Funded by club owner Roman Abramovich. The name “49 Flames” reFers to the number oF Olympic medallists who were murdered during the Holocaust. The exhibition aims to tell the story oF the Holocaust through the eyes oF Jewish athletes. Of the 15 athletes Featured, proFiles highlighted include AlFred Flatow and Gustav Felix Flatow, German Jewish Gold medallists at the First modern Olympics held in Athens in 1896. The cousins, both gymnasts, would die oF starvation in the Theresienstadt concentration camp during the Holocaust. Also Featured is German Jewish track and Field athlete Lilli Henoch, who set 4 world records and won 10 German national championships, in Four diFFerent disciplines. In 1942, Lilli Henoch and her mother were deported to Riga where they were both murdered. The exhibition includes contributions From leading voices against antisemitism From around the world such as President oF Israel Reuven Rivlin, the Israeli politician and Human Rights activist Natan Sharansky, UK Government Antisemitism Adviser Lord John Mann, Lord Ian Austin, Karen Pollock oF the Holocaust Educational Trust, Jewish Agency Chairman Isaac Herzog, Holocaust survivor and champion weightliFter Sir Ben HelFgott, The Anti-DeFamation League’s (ADL) Sharon Nazarian and others. -

JULIUS HIRSCH -!Nie Wieder | Erinnerungstag Im Deutschen Fußball

Der Eintritt zu allen Veranstaltungen ist kostenlos! Sollten die Besucherkapazitäten bei den Veranstaltungen erreicht sein, kann leider kein weiterer Zutritt gewährt werden – in diesem Fall bittet der Veranstalter um Verständnis. Alle Veranstalter behalten sich vor, vom Hausrecht Gebrauch zu machen und Personen, die nazistischen Parteien oder Organisationen angehören, der nazistischen Szene zuzuordnen sind oder bereits in der Vergangenheit durch rassistische, nationalistische, antisemitische oder sonstige menschenverachtende Äußerungen in Erscheinung getreten sind, den Zutritt zur Veranstaltung zu verwehren oder von dieser auszuschließen. Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Steinwache Steinstraße 50 44147 Dortmund Telefon: 0231 50-25002 E-mail: [email protected] www.ns-gedenkstaetten.de/nrw/dortmund/besucherinformationen.html BORUSSEUM BVB | Fan- und Förderabteilung www.bvb-fanabteilung.de JULIUS HIRSCH BORUSSEUM Verstaltungsreihen in Erinnerung an den Fußballspieler Julius „Julle“ Hirsch BORUSSEUM Das Borussia Dortmund-Museum Strobelallee 50, 44139 Dortmund Telefon: 0231 9020-1368 Fax: 0231 9020-1344 E-Mail: [email protected] www.borusseum.de BORUSSEUM Julius Hirsch Veranstaltungsreihe in Erinnerung an den Julius Hirsch, Spitzname „Julle“ wurde am 7. April 1892 in Achern geboren. Er war Fußballspieler Julius „Julle“ Hirsch deutscher Fußballspieler, wurde 1910 mit seinem Heimatverein Karlsruher FV und In drei Veranstaltungen erinnern der BVB, die BVB | Fan- und Förderabteilung, das 1914 mit der SpVgg Fürth deutscher Meister und galt als einer der besten Stürmer. BORUSSEUM – das Borussia Dortmund-Museum und die Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Als Nationalspieler machte Hirsch sich zwischen 1911 und 1913 einen Namen, Steinwache an Julius Hirsch. dabei durfte er sieben Mal für die deutsche Nationalmannschaft auf dem Platz stehen. Als Jude wurde Julius Hirsch 1945 von den Nationalsozialisten verfolgt und wahrscheinlich nach Auschwitz-Birkenau deportiert und dort ermordet. -

Julius Hirsch Und Gottfried Fuchs – Deutsch-Jüdische Fußballpioniere, Deutsche Meister Und Nationalspieler

Julius Hirsch und Gottfried Fuchs – deutsch-jüdische Fußballpioniere, deutsche Meister und Nationalspieler Die Meistermannschaft des Karlsruher Fußballvereins (KFV), Fotografie aus dem Jahr 1910. Die bekanntesten Spieler des KFV waren die Nationalspieler Julius Hirsch (untere Reihe, zweiter von rechts) und Gottfried Fuchs (untere Reihe, erster von links).. © https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karlsruher_FV Julius Hirsch 1892 Julius Hirsch wird in Achern geboren, sein Vater ist ein Karlsruher Textilkaufmann. 1898- Julius Hirsch wird in Karlsruhe eingeschult und schließt seine 1908 Schullaufbahn mit der Mittleren Reife ab. Danach besucht er die Handelsschule und macht eine Lehre bei einer Lederhandlung. 1902 Julius Hirsch tritt in den Karlsruher Fußballverein (KFV) ein. 1901- Der KFV wird fünfmal hintereinander süddeutscher Meister und 1905 1905 zudem deutscher Vizemeister. 1905 bezieht der Verein ein neues Stadion bei der Telegrafenkaserne in der Nordweststadt. 1909 Fuchs wird als Linksaußen und auf halblinker Position Stammspieler in Arbeitskreis für Landeskunde/Landesgeschichte RP Karlsruhe www.landeskunde-bw.de der ersten Mannschaft des KFV. 1910 Fuchs wird mit dem KFV süddeutscher und deutscher Meister. Er und seine Mannschaftskameraden Gottfried Fuchs und Fritz Förderer tragen als Sturmspieler entscheidend zum Gewinn der Meisterschaft bei. Der 1897 geborene Sepp Herberger (Bundestrainer 1954) ist ein großer Fan von Fuchs, Förderer und Hirsch. 1911-12 Hirsch wird mit dem KFV zweimal süddeutscher Meister und einmal deutscher Vizemeister. 1911- Hirsch wird siebenmal für die deutsche Nationalmannschaft nominiert. 1913 Beim 5:5 gegen die Niederlande in Zwolle (1912) schießt er vier Tore. 1912 Militärdienst und Umzug nach Nürnberg, wo Hirsch in der Spielwarenfabrik „Gebrüder Bing AG“ arbeitet. Teilnahme an den Olympischen Spielen in Stockholm als Spieler der deutschen Nationalmannschaft 1914 Hirsch wird deutscher Meister mit der SpVgg Fürth. -

Auf Den Spuren Von Julius Hirsch

AUF DEN SPUREN VON JULIUS HIRSCH DIE DEPORTATION NACH AUSCHWITZ IM MÄRZ 1943 IMPRESSUM Herausgeber: DFB-Kulturstiftung Otto-Fleck-Schneise 6 60528 Frankfurt/Main Verantwortlich für den Inhalt: Olliver Tietz Texte: Sofern nicht anders gekennzeichnet, alle historischen Texte von Juliane Röleke und Dr. Andreas Kahrs Redaktion: Robert Claus, Maren Feldkamp, Dr. Andreas Kahrs, Daniel Lörcher, Juliane Röleke, Eberhard Schulz, Olliver Tietz Layout und Produktion: b2 mediadesign Ulanenplatz 2 · 63452 Hanau [email protected] AUF DEN SPUREN VON JULIUS HIRSCH STATIONEN UND OPFER DER DEPORTATION 33 DIE DEPORTATION NACH AUSCHWITZ STUTTGART Stuttgart/Karlsruhe 34 IM MÄRZ 1943 Chaskel Schlüsselberg 36 TRIER Trier 38 Heinz Kahn 40 DÜSSELDORF/ Düsseldorf/Essen 42 ESSEN Elfriede Falkner 44 Imo Moszkowicz 46 DORTMUND Dortmund 48 Hans Frankenthal 50 PADERBORN Paderborn 52 Peter Wolff 54 BIELEFELD Bielefeld 56 Lotte Windmüller / Paul Hoffmann 58 Familie Voos 62 HANNOVER Hannover 66 Familie Alexander 68 VORWORT 4 Exkurs: Felix Linnemann und die Deportation der Sinti und Roma 70 ZUR ENTSTEHUNG UND ZUM EINSATZ DER MATERIALIEN 6 DRESDEN Dresden 72 Justin Sonder 74 DER KARLSRUHER KAUFMANN UND Heinz Meyer 76 FUSSBALLSPIELER JULIUS HIRSCH 10 DAS DEUTSCHE KONZENTRATIONS- UND DIE DEPORTATION VON JULIUS HIRSCH VERNICHTUNGSLAGER AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU 78 IM KONTEXT DER NATIONALSOZIALISTISCHEN VERNICHTUNGSPOLITIK 24 AUSGEWÄHLTE LITERATUR UND LINKS 92 VORWORT Unter den Lebensgeschichten der im Nationalsozialismus verfolgten Die vorliegende Publikation ist ein Teil dieser Erinnerungskultur des und ermordeten Sportler*innen ist die Biografie von Julius Hirsch heute Fußballs. Der Name des Karlsruher Kaufmanns und Nationalspielers historisch gründlich, ja vorbildlich erschlossen. Damit ist sie eine sel- Julius „Juller“ Hirsch ist heute im und zum Teil sogar über den Fußball tene Ausnahme.