Constructing America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dictée 02 Octobre 2017 Le Réveil De La Maison. G Duhamel

Dictée du 02 octobre 2017 LE REVEIL DE LA MAISON G. DUHAMEL (Les plaisirs et les jeux) Une mouche, encore somno lent e, traverse la chambre à l’aveuglette, se heurte au mur, bourdonne avec rage et se rendort. Du fond de l’infini, un bruit régulier comme celui d’une horloge, plus marqué de secon de en secon de : un pas sur la route, le pas de l’ouvrier matinal ; des coups sourds, p esants et, par- dessous, le crépitement du gravier meur tri . Le pas approche ; dans un coin de la chambre, un objet attentif vibre délicatement, au rythme du marcheur. Puis le pas s’évanouit, comme s’il avait tourné de l’autre côté du monde. Qu’est-ce donc ? La nuit à son tour semble fissur ée , bless ée . Trois images bleues ém ergent des ténèbres. Les fenêtres ! l’aube ! Si pâle qu’elle ne pourra jamais venir à bout de tout ce noir… Un petit oiseau se met à chanter, tout seul, dans le marronnier. Il est au sommet des ramures. Sa chanson, tout ébo uriffé e, tombe en éte ndant les ailes. L’homme écoute, écoute. Son corps se rassemble autour de lui ; comme l’équipe des t âc herons à l’appel du mét ayer . Présent ! Présent ! Et, tout à coup, venue des entrailles de la maison, une petite voix humaine, nette, mélodieuse, dansante, prononce des mots que l’on ne comprend pas. Une autre voix lui répond, aussi faible, aussi pure, aussi joyeuse. Les deux voix s’e mm êlent, s’enrouent, s’enlacent, s’élancent. -

Julius Hirsch Nationalspieler - Ermordet Aber Nicht Vergessen!

in Gedenken an Julius Hirsch Nationalspieler - ermordet aber nicht vergessen! Mannschaftsbild des KFV 1910, stehend von links: Hüber, Burger, Tscherter, Ruzek, Breunig, Hollstein, Bosch, Gros. Sitzend von links: Förderer, Schwarze, Hirsch, Fuchs, Kächele. Julius Hirsch – 07.04.1892 - 08.05.1945 (für tot erklärt ) Julius Hirsch ist als jüngster Sohn, als eines von insgesamt sieben Kindern in Achern auf die Welt gekommen. Mit 6 Jahren wurde er in Karlsruhe eingeschult und beende- te seine Schulzeit mit der mittleren Reife. Daraufhin besuchte er eine Handelsschule und machte eine Lehre als Kaufmann bei der Karlsruher Lederhandlung Freund und Strauss. Dort arbeitete er bis zum 22.03.1912. Hirsch mit Förderer und Fuchs auf dem Cover von „Süddeutscher Julius Hirsch auf dem Cover von „Fußball“, 1922. Illustrierter Sport“, 1921. Ab dem 07.08.1914 diente er als Soldat im Ersten Weltkrieg und erreichte innerhalb von vier Dienstjahren den Rang des Vizefeldwebels und wurde mit dem Eisernen Kreuz II. Klasse ausgezeichnet. Nach dem Krieg arbeitete er bei der Nürnberger Bing AG und kehrte erst danach zum 01.04.1919 zurück nach Karlsruhe in die Deutsche Signalflaggenfabrik seines Vaters. 1920 heiratete er die gebürtige Karlsruherin Ella Karolina Hauser und bekam 1922 und 1928 die Kinder Heinold Leopold und Esther Carmen. 1926 bekamen Julius und sein Bruder Max die Geschäftsanteile des Vaters an dem Unternehmen. Allerdings wurde am 10.02.1933 das Konkursverfahren über das Un- ternehmen eröffnet und jenes liquidiert, wegen einer Bürgschaft die Max Hirsch ge- geben hatte. Der nun nach Arbeit suchende Hirsch ging in die Schweiz und anschließend in den Elsass und trat dort eine Trainerstelle bei der F.A. -

The Soldier's Death

The Soldier’s Death 133 The Soldier’s Death: From Valmy to Verdun Ian Germani Introduction In 1975, André Corvisier published an article in the Revue Historique entitled simply “The Death of the Soldier since the End of the Middle Ages.”1 Corvisier acknowledged both the immensity of the topic and the need for an interdisciplinary approach to its study. The claims he made for his own contribution were modest: he had done no more than to establish an inventory of questions, accompanied by a few reflections. The article was more important than these claims suggest. Its insistence upon the need to situate military death in relation to the broader experience of death in western civilization made it an exemplar of what historians were just beginning to refer to as “the New Military History.” Furthermore, in its tripartite consideration of the soldier’s death – covering, broadly speaking, soldiers’ own attitudes toward death, the relationship between military death and mortality in general as well as cultural representations of the soldier’s death – the article identified and mapped out for further study several important dimensions of the topic. In particular, as cultural history has become increasingly important, Corvisier’s attention to military culture as well as to the representations of the soldier’s death in literature and art seems particularly advanced. Evidently, many other historians have since taken up Corvisier’s challenge to consider in greater depth cultural representations of the soldier’s death. The First World War, as a conflict marked by unprecedented military mortality, has inspired a number of important histories that address this theme. -

Bibliographie - Maurice Genevoix Novembre 2019

Bibliographie - Maurice Genevoix Novembre 2019 *la Bibliothèque de l’Ecole Normale possède l'édition originale de certains titres, signalée par un astérisque. Romans et récits • *Sous Verdun, août-octobre 1914, E. Lavisse (préf.), Paris, Hachette, coll. « Mémoires et récits de guerre », 1916. H M gé 949 A 8° • *Nuits de guerre, Hauts de Meuse, Paris, Flammarion, 1917. H M gé 120 12° • *Nuits de guerre, Hauts de Meuse, Paris, Flammarion, 1929. H M gé 119 12° • *Au seuil des guitounes, Paris, Flammarion, 1918. H M gé 120 A 12° • *Jeanne Robelin, Paris, Flammarion, 1920. L F r 189 12° • *La Boue, Paris, Flammarion, 1921. H M gé 120 B 12° • *Remi des Rauches, Paris, Flammarion, 1922. L F r 189 A 12° • *La Joie, Paris, Flammarion, 1924. L F r 189 B 12° • *Euthymos, vainqueur olympique, Paris, Flammarion, 1924. L F r 189 C 12° • *Raboliot, Paris, Grasset, 1925. (Prix Goncourt 1925) L F r 189 D 12° • *La Boîte à pêche, Paris, Grasset, 1926. L F r 189 E 12° • *Les Mains vides, Paris, Grasset, 1928. L F r 189 F 12° • Rroû, Paris, Flammarion, 1964. L F r 267 8° • *Forêt voisine, Paris, Flammarion, 1933. L F r 268 8° • La Dernière Harde, Paris, Flammarion, 1988. L F r 189 K 12° • La Forêt perdue, Paris, Flammarion, 1996. L F r 189 L 12° • *La Mort de près (essai), Paris, Plon, 1972. L F r 189 M 12° 1 • *Trente Mille Jours (autobiographie), Paris, Seuil, 1980. L F r 265 8° • La Maison du souvenir, L. Campa (éd.), Paris, La Table ronde, 2013. -

Information Issued by the Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain • Fairfax Mansions

Vol. XVII No. 7 July, 1962 INFORMATION ISSUED BY THE ASSOCIATION OF JEWISH REFUGEES IN GREAT BRITAIN • FAIRFAX MANSIONS. FINCHLEY RD. (corner Fairfax Rd.). London. N.W.I Offset and ConMuUiitg Hours: Telephone: MAIda Vale 9096/7 (General OIkce and Welfare tor tha Aged) Moi\day to Thursday 10 a.in.—I p.m. 3—6 p.m MAIda Vale 4449 (Employment Agency, annually licensed bv the L.C.C,, and Social Services Dept.) Friday 10 ajn.—l p.m. Ernst Kahn Austrian baroque civilisation, tried to cope with their situation. Schnitzler, more fortunate than Weininger, if only through his exterior circum stances, knew much about the psychological struc THE YOUNG GENERATION CARRIES ON ture of Viennese middle-class s(Kiety and Jewry. The twilight, uncertainly and loneliness of the human soul attracted him, but his erotism is half- Sixth Year Book of the Leo Baeck Institute playful, half-sorrowful and does not deceive him about the truth that ". to write means to sit Those amongst us who remember our German- To some extent these achievements were due to in judgment over one's self". It enabled him to Jewish past are bound to wonder who will carry the Rabbi's charm which attracted Polish Jews objectivise the inner struggles of Jews who sought On with the elucidation of the relevant problems and German high-ranking officers and aristocrats the " Way into the Open ", i.e., into assimilation in once the older witnesses are no longer available. alike with whom he collaborated very closely. its different forms. The Year Book 1961* brings this home to us by This went so far that the German officials called Weininger. -

Duhamel's Attitudes As Expressed in the Salavin and Pasquier Series

DUHAMEL'S ATTITUDES AS EXPRESSED IN THE SALAVIN AND PASQUIER SERIES A Thesis Presented to The Department of Foreign Languages and the Graduate Council Kansas State Teachers College, Emporia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Martha Willems April 1968 110unoO a~~np~JD aq~ JOJ paAoJddy '~:lt '\kC ~i\;v-;\(L ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The writer wishes to express her sincere appreciation to Dr. Minnie M. Miller, Professor of Foreign Languages, Kansas State Teachers College of Emporia, my advisor in the preparation of this thesis. M. W. TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. PREFACE ••••• • • • • • • • • • · . 1 II. THE LIFE OF GEORGES DUHAMEL •• •• • • • •• • • 4 Duhamel's Family Background • • • • • • • • • • 4 Duhamel's Educati on •••• • • • ••• • • • • 5 Duhamel's Medical Profession • • • • • • • • • • 7 Duhamel's Career as a Writer. • • • • • •• • • 11 TIlo DUHAMEL'S ATTITUDE TOWARD FRIENDSHIP ••••••• 22 IV. DUHAMEL'S ATTITUDE TOWARD KINDNESS •••••••• 54 V. DUHAMEL'S ATTITUDE TOWARD MATERIAL POSSESSIONS •• 59 VI. CONCLUSIONS •••••••••••••••••• 0 65 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 68 APPENDIX • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 75 CHAPTER I PREFACE One of Georges Duhamel's outstanding qualities was his concern for mankind. He himself came from a family of the petite bourgeoisie. Duhamel especially admired les petites gens for their courage, the manner in which they undertook their work in the midst of difficulty, and the gaiety with which they accomplished the hardest and most thankless tasks. He was a moralist, a doctor of medicine, and a keen observer of people. As a surgeon in the First World War, he helped the wounded, the physically handicapped, and the mentally disturbed o Deeply moved by what he observed at first-hand, he foresaw that the world was in need of une nouvelle civilisa~ion. -

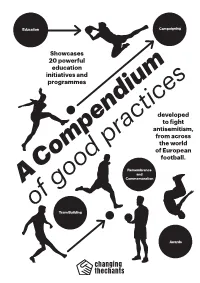

A Compendium of Good Practices

1 Education Campaigning Showcases 20 powerful education initiatives and programmes developed to fight antisemitism, from across the world of European football. CompendiumRemembrance and A Commemoration of good practices Team Building Awards 2 What are you reading ? This Compendium of good practices showcases 20 power- ful education initiatives and programmes, developed to fight antisemitism, from across the world of European football. The Compendium is not the definitive list of all noteworthy initiatives, nor is it an evaluation of a selection of programmes which are considered to be the best which exist; its aim is, rather, to highlight some of the existing practices - from workshops to commemoration plaques and remembrance trips to online campaigns – in the hope they might spark interest and motivate clubs, associations, fan groups and other stakeholders within or associated with the football community to develop their own practices. The initiatives were selected as a result of research conducted by a group of eight researchers and experts from across Europe who were all part of the Changing the Chants project. They conducted desk research and interviewed stake- holders connected to these initiatives. As a result, for every initiative the Compendium provides project background and context and an overview of what took place. Due to the limited scope of this Compendium, it has not been possible to analyse all these good practices in great depth and, as such, readers of this Compendium are invited and encouraged to seek out further information where further detail has not been provided. Categorization The practices have been categorised against five overarching themes: Campaigning (1), Education (2), Remembrance and com- memoration (3), Network building (4) and Awards (5). -

Whole Dissertation Hajkova 3

Abstract This dissertation explores the prisoner society in Terezín (Theresienstadt) ghetto, a transit ghetto in the Protectorate Bohemia and Moravia. Nazis deported here over 140, 000 Czech, German, Austrian, Dutch, Danish, Slovak, and Hungarian Jews. It was the only ghetto to last until the end of Second World War. A microhistorical approach reveals the dynamics of the inmate community, shedding light on broader issues of ethnicity, stratification, gender, and the political dimension of the “little people” shortly before they were killed. Rather than relegating Terezín to a footnote in narratives of the Holocaust or the Second World War, my work connects it to Central European, gender, and modern Jewish histories. A history of victims but also a study of an enforced Central European society in extremis, instead of defining them by the view of the perpetrators, this dissertation studies Terezín as an autarkic society. This approach is possible because the SS largely kept out of the ghetto. Terezín represents the largest sustained transnational encounter in the history of Central Europe, albeit an enforced one. Although the Nazis deported all the inmates on the basis of their alleged Jewishness, Terezín did not produce a common sense of Jewishness: the inmates were shaped by the countries they had considered home. Ethnicity defined culturally was a particularly salient means of differentiation. The dynamics connected to ethnic categorization and class formation allow a deeper understanding of cultural and national processes in Central and Western Europe in the twentieth century. The society in Terezín was simultaneously interconnected and stratified. There were no stark contradictions between the wealthy and majority of extremely poor prisoners. -

Maurice Genevoix Novembre 2019-2020

Bibliographie - Maurice Genevoix Novembre 2019-2020 *la Bibliothèque de l’Ecole Normale possède l'édition originale de certains titres, signalée par un astérisque. Romans et récits • *Sous Verdun, août-octobre 1914, E. Lavisse (préf.), Paris, Hachette, coll. « Mémoires et récits de guerre », 1916. H M gé 949 A 8° • *Nuits de guerre, Hauts de Meuse, Paris, Flammarion, 1917. H M gé 120 12° • *Nuits de guerre, Hauts de Meuse, Paris, Flammarion, 1929. H M gé 119 12° • *Au seuil des guitounes, Paris, Flammarion, 1918. H M gé 120 A 12° • *Jeanne Robelin, Paris, Flammarion, 1920. L F r 189 12° • *La Boue, Paris, Flammarion, 1921. H M gé 120 B 12° • *Remi des Rauches, Paris, Flammarion, 1922. L F r 189 A 12° • *La Joie, Paris, Flammarion, 1924. L F r 189 B 12° • *Euthymos, vainqueur olympique, Paris, Flammarion, 1924. L F r 189 C 12° • *Raboliot, Paris, Grasset, 1925. (Prix Goncourt 1925) L F r 189 D 12° • *La Boîte à pêche, Paris, Grasset, 1926. L F r 189 E 12° • *Les Mains vides, Paris, Grasset, 1928. L F r 189 F 12° • Rroû, Paris, Flammarion, 1964. L F r 267 8° • *Forêt voisine, Paris, Flammarion, 1933. L F r 268 8° • La Dernière Harde, Paris, Flammarion, 1988. L F r 189 K 12° • La Forêt perdue, Paris, Flammarion, 1996. L F r 189 L 12° • *La Mort de près (essai), Paris, Plon, 1972. 1 L F r 189 M 12° • *Trente Mille Jours (autobiographie), Paris, Seuil, 1980. L F r 265 8° • La Ferveur du souvenir, L. Campa (éd.), Paris, La Table ronde, 2013. -

From Flaubert to Sartre1

THE WRITER’S RESPONSIBILITY IN FRANCE From Flaubert to Sartre1 Gisèle Sapiro Centre national de la recherche scientifique As Michel Foucault observed in his famous essay, “Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur?” before discourse was a product, it was an act that could be punished.2 The author’s appropriation of discourse as his personal property is secondary to its ascription to his name through penal responsibility. In France, authorial responsibility was introduced in 1551 through royal legislation directed at controlling the book market. The Chateaubriant edict made it compulsory to print both the author’s and the printer’s names on any publication. The notion of responsibility is thus a fundamental aspect of the emergence of the figure of the modern writer. The state first imposed this conception of respon- sibility in order to control the circulation of discourses. But after writers inter- nalized the notion, they deployed it against the state in their struggle to establish their moral right on their work and to have literary property recog- nized as individual property, a struggle that culminated in 1777 with a royal decree recognizing literary compositions as products of labor from which authors were entitled to derive an income.3 This professional development reinforced the writer’s social prestige and status, in Max Weber’s sense.4 The withdrawal of the state from the control of the book market and the abjuration of censorship entailed the need for new legislation restricting the principle of freedom of speech, which had been proclaimed in Article XI of the 1789 Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du citoyen. -

Livres Reçus

Document generated on 09/29/2021 3:11 a.m. Nuit blanche Livres reçus Bachelard, philosophe et poète. 1884-1962 Number 13, April–May 1984 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/21536ac See table of contents Publisher(s) Nuit blanche, le magazine du livre ISSN 0823-2490 (print) 1923-3191 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document (1984). Livres reçus. Nuit blanche, (13), 86–88. Tous droits réservés © Nuit blanche, le magazine du livre, 1984 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Livres reçus Littérature étranger* Le petit monde de Don Camillo Le tombeau de l'éclair Chardonne Giovanni Guareschi Manuel Scorza Ginette Guitard-Auviste Seuil, coll. Points Belfond Olivier Orban Visages d'Alice Les jeux du tour de ville La belle Otcro L'aura humaine ou les illustrateurs d'Alice Daniel Boulanger Charles Castle Winifred G. Barton Collectif Gallimard Belfond Éd. de Mortagne Gallimard Un homme au singulier En ce moment précis Les bons vins et les autres Le message d'Eykis Christopher Isherwood DinoBuzzati Pierre-Marie Doutrelant Dr Wayne Dyer Seuil, coll. Points Robert Laffont, coll. 10/18 Seuil, coll. Points Éditions de Mortagne Drageoir Correspondance de Marcel Proust La culture contre la démocratie? L'Harmonica-Zug Daniel Boulanger Tome XI A. -

Georges Duhamel Et Charles Vildrac Face À L'au-Dessus De La Mêlée De

Georges Duhamel et Charles Vildrac face à l’ Au-dessus de la mêlée de Romain Rolland par Bernard Duchatelet* Les Amis de Georges Duhamel et de l’Abbaye de Créteil ont organisé Le 29 novembre 2008, à Péronne, à l’Historial de la Grande Guerre un colloque sur le thème : « Autour de Georges Duhamel. Écrire la Grande Guerre ». Ce colloque réunissait Jean-Jacques Becker, Bernard Duchatelet, Laurence Campa, Nicolas Beaupré, Myriam Boucharenc. Le professeur Duchatelet est intervenu sur « Georges Duhamel et Charles Vildrac face à l’ Au- dessus de la mêlée de Romain Rolland ». Nous remercions Mme Laurence Campa pour les Amis de Georges Duhamel, de nous autoriser à reproduire in extenso la conférence de Bernard Duchatelet dans les Cahiers de Brèves . Les Cahiers de l’Abbaye de Créteil ont publié dans leur numéro 27 de décembre 2008, les Actes de ce colloque. Actuellement, Bernard Duchatelet prépare l’édition de la correspondance échangée entre les Rolland et les Duhamel. L’essentiel est composé, bien sûr, de l’échange des lettres de Rolland et de Duhamel, mais on trouve aussi des lettres de Madeleine et de Marie Rolland à Duhamel et de Blanche Duhamel à Rolland. A ces lettres s’ajoute - ront d’autres documents qui complètent cet ensemble : les dédicaces des livres envoyés, et aussi des passages des journaux de l’un et de l’autre, ou des extraits de lettres à des tiers, qui parfois permettent de mieux comprendre la tonalité de certaines lettres. La plupart des documents sont rassemblés. Il faut mettre le tout en forme et prévoir les notes indispensables.