DOCUMENT RESUME ED 372 022 SO 024 307 AUTHOR Harris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Thüringer CDU in Der SBZ/DDR – Blockpartei Mit Eigeninteresse

Bertram Triebel Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ/DDR – Blockpartei mit Eigeninteresse Bertram Triebel Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ/DDR Blockpartei mit Eigeninteresse Herausgegeben im Auftrag der Unabhängigen Historischen Kommission zur Geschichte der CDU in Thüringen und in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl von 1945 bis 1990 von Jörg Ganzenmüller und Hermann Wentker Herausgegeben im Auftrag der Unabhängigen Historischen Kommission zur Geschichte der CDU in Thüringen und in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl von 1945 bis 1990 von Jörg Ganzenmüller und Hermann Wentker Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Weiterverwertungen sind ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer- Stiftung e.V. unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. © 2019, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin Umschlaggestaltung: Hans Dung Satz: CMS der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Druck: Kern GmbH, Bexbach Printed in Germany. Gedruckt mit finanzieller Unterstützung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. ISBN: 978-3-95721-569-7 Inhaltsverzeichnis Geleitworte . 7 Vorwort . 13 Einleitung . 15 I. Gründungs- und Transformationsjahre: Die Thüringer CDU in der SBZ und frühen DDR (1945–1961) 1. Die Gründung der CDU in Thüringen . 23 2. Wandlung und Auflösung des Landesverbandes . 32 3. Im Bann der Transformation: Die CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl bis 1961 . 46 II. Die CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl – Eine Blockpartei im Staatssozialismus (1961–1985) 1. Die Organisation der CDU . 59 1.1. Funktion und Parteikultur der CDU . 60 1.2. Der Apparat der CDU in den Bezirken Erfurt, Gera und Suhl . 62 1.3. -

Über Gegenwartsliteratur About Contemporary Literature

Leseprobe Über Gegenwartsliteratur Interpretationen und Interventionen Festschrift für Paul Michael Lützeler zum 65. Geburtstag von ehemaligen StudentInnen Herausgegeben von Mark W. Rectanus About Contemporary Literature Interpretations and Interventions A Festschrift for Paul Michael Lützeler on his 65th Birthday from former Students Edited by Mark W. Rectanus AISTHESIS VERLAG ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Bielefeld 2008 Abbildung auf dem Umschlag: Paul Klee: Roter Ballon, 1922, 179. Ölfarbe auf Grundierung auf Nesseltuch auf Karton, 31,7 x 31,1 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. © VG BILD-KUNST, Bonn 2008 Bibliographische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliographie; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.ddb.de abrufbar. © Aisthesis Verlag Bielefeld 2008 Postfach 10 04 27, D-33504 Bielefeld Satz: Germano Wallmann, www.geisterwort.de Druck: docupoint GmbH, Magdeburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten ISBN 978-3-89528-679-7 www.aisthesis.de Inhaltsverzeichnis/Table of Contents Danksagung/Acknowledgments ............................................................ 11 Mark W. Rectanus Introduction: About Contemporary Literature ............................... 13 Leslie A. Adelson Experiment Mars: Contemporary German Literature, Imaginative Ethnoscapes, and the New Futurism .......................... 23 Gregory W. Baer Der Film zum Krug: A Filmic Adaptation of Kleist’s Der zerbrochne Krug in the GDR ......................................................... -

A Genealogical Handbook of German Research

Family History Library • 35 North West Temple Street • Salt Lake City, UT 84150-3400 USA A GENEALOGICAL HANDBOOK OF GERMAN RESEARCH REVISED EDITION 1980 By Larry O. Jensen P.O. Box 441 PLEASANT GROVE, UTAH 84062 Copyright © 1996, by Larry O. Jensen All rights reserved. No part of this work may be translated or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the author. Printed in the U.S.A. INTRODUCTION There are many different aspects of German research that could and maybe should be covered; but it is not the intention of this book even to try to cover the majority of these. Too often when genealogical texts are written on German research, the tendency has been to generalize. Because of the historical, political, and environmental background of this country, that is one thing that should not be done. In Germany the records vary as far as types, time period, contents, and use from one kingdom to the next and even between areas within the same kingdom. In addition to the variation in record types there are also research problems concerning the use of different calendars and naming practices that also vary from area to area. Before one can successfully begin doing research in Germany there are certain things that he must know. There are certain references, problems and procedures that will affect how one does research regardless of the area in Germany where he intends to do research. The purpose of this book is to set forth those things that a person must know and do to succeed in his Germanic research, whether he is just beginning or whether he is advanced. -

13. Parteitag Der Cdu Deutschlands

13. PARTEITAG DER CDU DEUTSCHLANDS 9.-11. April 2000 Grugahalle Essen PROTOKOLL 13. Parteitag der Christlich Demokratischen Union Deutschlands Niederschrift Essen, 10./11. April 2000 Herausgeber: Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands, Bundesgeschäftsstelle, 53113 Bonn, Konrad-Adenauer-Haus Verlag und Gesamtherstellung: Union Betriebs-GmbH, Egermannstraße 2, 53359 Rheinbach 2 I N H A L T Seite Eröffnung und Begrüßung: Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble, Vorsitzender der CDU Deutschlands 7 Wahl des Tagungspräsidiums 10 Grußwort des Vorsitzenden des CDU-Landesverbandes Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dr. Jürgen Rüttgers 10 Beschlussfassung über die Tagesordnung 14 Bestätigung der Antragskommission 15 Wahl der Mandatsprüfungskommission 15 Wahl der Stimmzählkommission 16 Grußworte – Dr. Wolfgang Reiniger, Oberbürgermeister der Stadt Essen 16 – Ministerpräsident a.D. Wilfried Martens, Vorsitzender der Europäischen Volkspartei 18 – Vizepremierminister Sauli Niinistö, Vorsitzender der Europäischen Demokratischen Union 19 Bericht des Vorsitzenden der CDU Deutschlands, Dr. Wolfgang Schäuble 21 Aussprache zum Bericht des Vorsitzenden 35 Bericht des Bundesschatzmeisters der CDU Deutschlands, Matthias Wissmann, zugleich Einführung in die Anträge des Bundesvorstandes der CDU Deutschlands zu den Konsequenzen der Finanzaffäre 54 Bericht der Rechnungsprüfer 61 Bericht der Mandatsprüfungskommission 64 Aussprache zu den Berichten des Bundesschatzmeisters und der Rechnungsprüfer sowie Beschlussfassung zu den Anträgen des Bundesvorstandes 64 3 Entlastung des Bundesvorstandes -

Bilingual Education for All!

52 Free things to do in new York May 2019 established 1986 NewyorkFamily.com Hilaria Baldwinon marriage to Alec, w w w their four kids, . newyorkfamily and parenting authentically . c o m BilinguAl educAtion for All! THE PERFECT CAMP TO FIT YOUR SUMMER PLANS Preschool + Junior Camps • Sports Academy Gymnastics • Ninja Parkour • Golf • Basketball Elite Soccer • Ice Hockey • Ice Skating Urban Adventure for Teens JUNE 17 - AUGUST 30, 2019 Flexible Weeks Hot Lunch Provided Transportation & Aftercare Available Waterslide • Color Wars • Gymnastics Shows Kayaking • Golf Trips • Bowling • Skating Shows Hockey Games • Cruises & much more! EARLY BIRDS: Register by May 17 + Save! chelseapiers.com/camps May 2019 | newYorkfamily.com 3 contents MaY 2019 newyorkfamily.com pg. 12 pg. 32 pg. 64 pg. 52 pg. 38 62 | giving Back FEATURES columns Help Feed Kids in Need. Donate to this City Harvest fund-raiser that 38 | the Juggle is real For hilaria 6 | editor’s note helps feed New york’s children Baldwin May Flowers Hilaria Baldwin gets real with us 74 | Family day out about being a mom to four under five 8 | Mom hacks Harry Potter Café. Step into Steamy and her passion for healthy living Shopping experts The Buy Guide share Hallows in the East Village with this their mom must-haves for city living fun pop-up café full of wizardly 44| Bilingual education guide wonder New york City kids have many 12 | ask the expert - keeping girls options for a bilingual education, we in sports have the ultimate guide to finding the Dr. Karen Sutton talks about why hoMe & -

Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg STAATSMINISTERIUM PRESSESTELLE DER LANDESREGIERUNG PRESSEMITTEILUNG Nr. 113/2007 12. April 2007 Ansprache des baden-württembergischen Ministerpräsidenten Günther H. Oettinger anlässlich des Staatsakts zum Tod von Ministerpräsident a. D. Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Hans Filbinger im Frei- burger Münster Verehrte liebe Frau Filbinger, liebe Familie Filbinger, ich grüße die fünf Kinder, 14 Enkelkinder, zwei Urenkel, und alle Angehörige, Herr Landtagspräsident, Herr Bundesminister, lieber Lothar Späth, lieber Erwin Teufel, verehrte Vertreter der Regierung und von Bayern, Hessen und Nordrhein-Westfalen, verehrte akti- ve und ehemalige Mitglieder der Landesregierung Baden-Württembergs, des Deutschen Bundestages und des Landtags von Baden-Württemberg, Herr O- berbürgermeister, Herr Weihbischof Klug, verehrte Vertreter der Kirchen, liebe Freunde und Weggefährten von Hans Filbinger, verehrte Trauergemeinde, Tief bewegt nehmen wir Abschied von Hans Karl Filbinger. In Trauer, aber auch voller Respekt und Hochachtung verneigen wir uns vor ei- ner großen Persönlichkeit, einem herausragenden Politiker und vor seinem Le- benswerk. Unser Mitgefühl und unsere aufrichtige Anteilnahme gilt Ihnen, liebe Frau Filbinger und gilt den Kindern, den Enkeln und den Angehörigen. In christli- cher Verbundenheit teilen wir Ihre Trauer, auch wenn wir wissen, dass Worte und Gesten über den schweren Verlust nicht hinweghelfen können. Die Nach- richt vom Tode Hans Filbingers hat uns alle tief bewegt. Viele sind heute hier, die Hans Filbinger nahestanden: Persönlichkeiten des öf- fentlichen Lebens, Weggefährten, Mitarbeiter von einst und Freunde. Aus Günterstal, aus Freiburg, aus Südbaden, aus Baden-Württemberg und weit darüber hinaus. Richard-Wagner-Straße 15, 70184 Stuttgart, Telefon (0711) 21 53 - 213, Fax (0711) 21 53 - 340 E-Mail: [email protected], Internet: http://www.baden-wuerttemberg.de 2 Auch viele Bürger im Land denken in diesen Tagen an Hans Filbinger. -

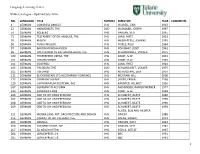

1 Language Learning Center Video Catalogue

Language Learning Center Video Catalogue – Updated July 2016 NO. LANGUAGE TITLE FORMAT DIRECTOR YEAR COMMENTS 4 GERMAN CONGRESS DANCES VHS CHARELL, ERIK 1932 22 GERMAN HARMONISTS, THE DVD VILSMAIER, JOSEPH 1997 54 GERMAN KOLBERG VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1945 71 GERMAN TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE, THE VHS LANG, FRITZ 1933 95 GERMAN MALOU VHS MEERAPFELE, JEANINE 1983 96 GERMAN TONIO KROGER VHS THIELE, ROLF 1964 97 GERMAN BARON MUNCHHAUSEN VHS VON BAKY, JOSEF 1943 99 GERMAN LOST HONOR OF KATHARINA BLUM, THE VHS SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 100 GERMAN THREEPENNY OPERA, THE VHS PABST, G.W. 1931 101 GERMAN JOYLESS STREET VHS PABST, G.W. 1925 102 GERMAN SIEGFRIED VHS LANG, FRITZ 1924 103 GERMAN TIN DRUM, THE DVD SCHLONDORFF, VOLKER 1975 105 GERMAN TIEFLAND VHS RIEFENSTAHL, LENI 1954 111 GERMAN BLICKKONTAKE (TO ACCOMPANY KONTAKE) VHS MCGRAW HILL 2000 127 GERMAN GERMANY AWAKE VHS LEISER, ERWIN 1968 129 GERMAN CAPTAIN FROM KOEPENIK, THE VHS KAUNTER, HELMUT 1956 167 GERMAN GERMANY IN AUTUMN VHS FASSBINDER, RANIER WERNER 1977 199 GERMAN PANDORA'S BOX VHS PABST, G.W. 1928 206 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 207 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 208 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 209 GERMAN ODE TO JOY AND FREEDOM VHS SCHUBERT, BEATE 1990 ROSEN, BOB AND ANDREA 211 GERMAN VIENNA 1900: ART, ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN VHS SIMON 1986 253 GERMAN CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, THE VHS WIENE, ROBERT 1919 265 GERMAN DAMALS VHS HANSEN, ROLF 1943 266 GERMAN GOLDENE STADT, DIE VHS HARLAN, VEIT 1942 267 GERMAN ZU NEUEN -

Shaken, Not Stirred: Markus Wolfâ•Žs Involvement in the Guillaume Affair

Voces Novae Volume 4 Article 6 2018 Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume Affair and the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Jason Hiller Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Hiller, Jason (2018) "Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume Affair nda the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR," Voces Novae: Vol. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol4/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hiller: Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume A Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 3, No 1 (2012) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 3, No 1 (2012) > Hiller Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf's Involvement in the Guillaume Affair and the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Jason Hiller "The principal link in the chain of revolution is the German link, and the success of the world revolution depends more on Germany than upon any other country." -V.I. Lenin, Report of October 22, 1918 The game of espionage has existed longer than most people care to think. However, it is not important how long ago it started or who invented it. What is important is the progress of espionage in the past decades and the impact it has had on powerful nations. -

Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination EDITED BY TARA FORREST Amsterdam University Press Alexander Kluge Alexander Kluge Raw Materials for the Imagination Edited by Tara Forrest Front cover illustration: Alexander Kluge. Photo: Regina Schmeken Back cover illustration: Artists under the Big Top: Perplexed () Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn (paperback) isbn (hardcover) e-isbn nur © T. Forrest / Amsterdam University Press, All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustra- tions reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. For Alexander Kluge …and in memory of Miriam Hansen Table of Contents Introduction Editor’s Introduction Tara Forrest The Stubborn Persistence of Alexander Kluge Thomas Elsaesser Film, Politics and the Public Sphere On Film and the Public Sphere Alexander Kluge Cooperative Auteur Cinema and Oppositional Public Sphere: Alexander Kluge’s Contribution to G I A Miriam Hansen ‘What is Different is Good’: Women and Femininity in the Films of Alexander Kluge Heide -

GESAMTARBEIT Kulturtechniken Des Kollektiven Bei Alexander Kluge

Jens Grimstein GESAMTARBEIT Kulturtechniken des Kollektiven bei Alexander Kluge Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Philosophie und Geisteswissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin Gutachterinnen und Gutachter: Erstgutachterin: Frau Prof. Dr. Irene Albers Zweitgutachter: Herr PD Dr. Wolfram Ette Tag der Disputation: 03. Juli 2019 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. Einleitung ............................................................................ 2 2. Begriffe (Theorie) ............................................................. 12 2.1. Kollektive................................................................................ 12 2.2. Kulturtechniken ...................................................................... 25 2.3. Arbeit ...................................................................................... 40 2.4. Gesamtarbeit ........................................................................... 47 3. Kluges Theoriearbeit (Theoros) ........................................ 57 3.1. Kluge und die Theorie ............................................................ 58 3.2. Kluge und die Kollektive ........................................................ 64 3.3. Kluge und die Kulturtechniken ............................................... 66 3.4. Die Kritische Theorie zwischen Aufklärung und Theorie der Kulturtechnik ............................................... 85 4. Medien (Textilia) .............................................................. 92 4.1. Zivilisation, Turm, Stadt -

Bosnia Herzegovina Seongjin Kim Equatorial Guinea 1 1 1 UNESCO 1

Committee Totals (GA, SPC, ICJ Judges ICJ Advocates ICJ Officers School Delegations GA SPC SC Total Total, SC) Opening Speeches GA Opening Speeches SPC Qatar Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 10 2 2 Oman Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 10 Sri Lanka Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 20 Bosnia Herzegovina Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 0 Camaroon Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 Gambia Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 Kiribati Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 Monaco Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 Romania Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 Solomon Islands Agora Sant Cugat International School 1 1 2 South Africa American International School of Bucharest 1 1 2 8 2 2 Seongjin Kim Serbia American International School of Bucharest 1 1 2 8 Andrew Weston Portugal American International School of Bucharest 1 1 2 16 Cambodia American International School of Bucharest 1 1 2 1 Central African Republic American International School of Bucharest 1 1 2 Equatorial Guinea American International School of Bucharest 1 1 1 2 Lithuania American International School of Bucharest 1 1 2 Mongolia American International School of Bucharest 1 1 2 USA American School of Barcelona 1 1 1 3 11 2 2 Norway American School of Barcelona 1 1 2 9 Argentina American School of Barcelona 1 1 2 20 Uraguay American School of Barcelona 1 1 2 1 Chad American School of Barcelona 1 1 2 Guinea Bissau American School of Barcelona 1 1 2 Kyrgyzstan American School of Barcelona 1 1 2 Montenegro -

The Cultural Memory of German Victimhood in Post-1990 Popular German Literature and Television

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 The ulturC al Memory Of German Victimhood In Post-1990 Popular German Literature And Television Pauline Ebert Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the German Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ebert, Pauline, "The ulturC al Memory Of German Victimhood In Post-1990 Popular German Literature And Television" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 12. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE CULTURAL MEMORY OF GERMAN VICTIMHOOD IN POST-1990 POPULAR GERMAN LITERATURE AND TELEVISION by ANJA PAULINE EBERT DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2010 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES Approved by: ________________________________________ Advisor Date ________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________________ ________________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ANJA PAULINE EBERT 2010 All Rights Reserved Dedication I dedicate this dissertation … to Axel for his support, patience and understanding; to my parents for their help in financial straits; to Tanja and Vera for listening; to my Omalin, Hilla Ebert, whom I love deeply. ii Acknowledgements In the first place I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Anne Rothe.